Hidden Communities Ferentari

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical GIS: Mapping the Bucharest Geographies of the Pre-Socialist Industry Gabriel Simion*, Alina Mareci, Florin Zaharia, Radu Dumitru

# Gabriel Simion et al. Human Geographies – Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography Vol. 10, No. 2, November 2016 | www.humangeographies.org.ro ISSN–print: 1843–6587 | ISSN–online: 2067–2284 Historical GIS: mapping the Bucharest geographies of the pre-socialist industry Gabriel Simion*, Alina Mareci, Florin Zaharia, Radu Dumitru University of Bucharest, Romania This article aims to map the manner in which the rst industrial units crystalized in Bucharest and their subsequent dynamic. Another phenomenon considered was the way industrial sites grew and propagated and how the rst industrial clusters formed, thus amplifying the functional variety of the city. The analysis was undertaken using Historical GIS, which allowed to integrate elements of industrial history with the location of the most important industrial objectives. Working in GIS meant creating a database with the existing factories in Bucharest, but also those that had existed in different periods. Integrating the historical with the spatial information about industry in Bucharest was preceded by thorough preparations, which included geo-referencing sources (city plans and old maps) and rectifying them. This research intends to serve as an example of how integrating past and present spatial data allows for the analysis of an already concluded phenomenon and also explains why certain present elements got to their current state.. Key Words: historical GIS, GIS dataset, Bucharest. Article Info: Received: September 5, 2016; Revised: October 24, 2016; Accepted: November 15, 2016; Online: November 30, 2016. Introduction The spatial evolution of cities starting with the ending of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th is closely connected to their industrial development. -

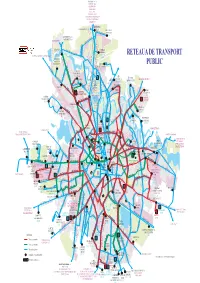

RETEA GENERALA 01.07.2021.Cdr

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 97 204 205 304 261 Sisesti BANEASA RETEAUA DE TRANSPORT R402 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 COMPLEX 112 205 261 97 131 261301 COMERCIAL Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti PUBLIC COLOSSEUM CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 203 335 361 605 780 783 112 R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 Bd. Aerogarii R402 97 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 24 331R436 CFR Str. Alex. Serbanescu 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 DRIDU Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 65 86 112 135 243 Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Bd. Gloriei24 Str. Jiului 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Sos. Chitilei Poligrafiei PIATA PLATFORMA Bd. BucurestiiPajurei Noi 231 243 Str. Peris MEZES 780 783 INDUSTRIALA Str. PRESEI Str.Oi 3 45 65 86 331 243 3 45 382 PASAJ Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 3 41 243 PIPERA 382 DEPOUL R447 R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 i 65 86 97 243 16 36 COLENTINA 131105 203 205 261203 304 231 261 304 330 135 343 n tuz BUCURESTII NOI a R441 R442 R443 c 21 i CARTIER 605 tr 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 DEPOUL Bd. -

People's Advocate

European Network of Ombudsmen THE 2014 REPORT OF PEOPLE’S ADVOCATE INSTITUTION - SUMMARY - In accordance with the provisions of art. 60 of the Constitution and those of art. 5 of Law no. 35/1997 on the organization and functioning of the People's Advocate Institution, republished, with subsequent amendments, the Annual Report concerning the activity of the institution for one calendar year is submitted by the People's Advocate, until the 1st of February of the following year, to Parliament for its debate in the joint sitting of the two Chambers. We present below a summary of the 2014 Report of the People’s Advocate Institution, which has been submitted to Parliament, within the legal deadline provided by Law no. 35/1997. GENERAL VOLUME OF ACTIVITY The overview of the activity in 2014 can be summarized in the following statistics: - 16,841 audiences , in which violations of individuals' rights have been alleged, out of which 2,033 at the headquarters and 14,808 at the territorial offices; - 10,346 complaints registered at the People's Advocate Institution, out of which 6,932 at the headquarters and 3,414 at the territorial offices; Of these, a total of 7,703 complaints were sent to the People's Advocate on paper, 2,551 by email, and 92 were received from abroad. - 8,194 calls recorded by the dispatcher service, out of which 2,504 at the headquarters and 5,690 at the territorial offices; - 137 investigations conducted by the People's Advocate Institution, out of which 33 at the headquarters and 104 at the regional offices; - 56 ex officio -

Download This PDF File

THE SOCIO-SPATIAL DIMENSION OF THE BUCHAREST GHETTOS Viorel MIONEL Silviu NEGUŢ Viorel MIONEL Assistant Professor, Department of Economics History and Geography, Faculty of International Business and Economics, Academy of Economic Studies, Bucharest, Romania Tel.: 0040-213-191.900 Email: [email protected] Abstract Based on a socio-spatial analysis, this paper aims at drawing the authorities’ attention on a few Bucharest ghettos that occurred after the 1990s. Silviu NEGUŢ After the Revolution, Bucharest has undergone Professor, Department of Economics History and Geography, many socio-spatial changes. The modifications Faculty of International Business and Economics, Academy of that occurred in the urban perimeter manifested Economic Studies Bucharest, Romania in the technical and urban dynamics, in the urban Tel.: 0040-213-191.900 infrastructure, and in the socio-economic field. The Email: [email protected] dynamics and the urban evolution of Bucharest have affected the community life, especially the community homogeneity intensely desired during the communist regime by the occurrence of socially marginalized spaces or ghettos as their own inhabitants call them. Ghettos represent an urban stain of color, a special morphologic framework. The Bucharest “ghettos” appeared by a spatial concentration of Roma population and of poverty in zones with a precarious infrastructure. The inhabitants of these areas (Zăbrăuţi, Aleea Livezilor, Iacob Andrei, Amurgului and Valea Cascadelor) are somehow constrained to live in such spaces, mainly because of lack of income, education and because of their low professional qualification. These weak points or handicaps exclude the ghetto population from social participation and from getting access to urban zones with good habitations. -

Rahova – Uranus: Un „Cartier Dormitor”?

RAHOVA – URANUS: UN „CARTIER DORMITOR”? BOGDAN VOICU DANA CORNELIA NIŢULESCU ahova–Uranus este o zonă a oraşului Bucureşti situată aproape de centru, însă, ca multe alte cartiere, lipsită aproape complet de orice R viaţă culturală. Studiul de faţă se referă la reprezentările tinerilor din zonă asupra cartierului lor. Folosind date calitative, arătăm că tinerii bucureşteni din Rahova văd în mizerie, aglomeraţie, trafic principalele probleme ale oraşului şi ale zonei în care trăiesc. Investigarea reprezentărilor şi comportamentelor de consum cultural ale tinerilor din cartierul bucureştean Rahova–Uranus relevă caracteristica zonei de a fi, în principal, un „cartier-dormitor”. Oamenii par a veni aici doar ca să locuiască, fiind preocupaţi mai ales în a dormi, a mânca, şi a-şi îndeplini nevoile fiziologice. Materialul de faţă utilizează rezultatele unei cercetări despre modul în care tinerii din zona Rahova – Uranus îşi satisfac nevoia de cultură. Cercetarea, iniţiată şi finanţată de British Council, parte a unui proiect mai larg gestionat de Centrul Internaţional pentru Artă Contemporană1, a fost realizată în octombrie 2006, implicând interviuri semistructurate, cu 26 de tineri între 17 şi 35 de ani. În articolul de faţă ne propunem să contribuim la o mai bună cunoaştere a locuitorilor tineri din zona Rahova – Uranus, identificând nevoile lor de natură culturală, precum şi comportamentele de consum cultural. Ne propunem o descriere, o prezentare de tip documentar a realităţilor observate, explicaţiei şi interpretării fiindu-le alocat un spaţiu mai restrâns. Studiul are în centrul său culturalul nevoia de frumos, cu alte cuvinte acea versiune a culturii în sensul dat de ştiinţele umane2. Suntem interesaţi în ce măsură 1 Mulţumim British Council şi CIAC pentru acceptul de a publica acest material, care utilizează în bună măsură textul raportului de cercetare realizat. -

Component 1. Elaboration of Bucharest's Iuds, Capital

ROMANIA Reimbursable Advisory Services Agreement on the Bucharest Urban Development Program (P169577) COMPONENT 1. ELABORATION OF BUCHAREST’S IUDS, CAPITAL INVESTMENT PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT Output 3. Urban context and identification of key local issues and needs, and visions and objectives of IUDS and Identification of a long list of projects. Chapter 3. Spatial and Functional Profile March 2021 DISCLAIMER This report is a product of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/the World Bank. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. This report does not necessarily represent the position of the European Union or the Romanian Government. COPYRIGHT STATEMENT The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable laws. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with the complete information to either: (i) the Municipality of Bucharest (Bd. Regina Elisabeta 47, Bucharest, Romania); or (ii) the World Bank Group Romania (Str. Vasile Lascăr 31, et. 6, Sector 2, Bucharest, Romania). This report was delivered in March 2021 under the Reimbursable Advisory Services Agreement on the Bucharest Urban Development Program, concluded between the Municipality of Bucharest and the -

Romania 2019 Human Rights Report

ROMANIA 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Romania is a constitutional republic with a democratic, multiparty parliamentary system. The bicameral parliament consists of the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies, both elected by popular vote. Observers considered presidential elections held on November 10 and 24 and parliamentary elections in 2016 to have been generally free and fair and without significant irregularities. The Ministry of Internal Affairs is responsible for the General Inspectorate of the Romanian Police, the gendarmerie, border police, the General Directorate for Internal Protection (DGPI), and the Directorate General for Anticorruption (DNA). The DGPI has responsibility for intelligence gathering, counterintelligence, and preventing and combatting vulnerabilities and risks that could seriously disrupt public order or target Ministry of Internal Affairs operations. The minister of interior appoints the head of DGPI. The Romanian Intelligence Service (SRI), the domestic security agency, investigates terrorism and national security threats. The president nominates and the parliament confirms the SRI director. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over SRI and the security agencies that reported to the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Significant human rights issues included: police violence against Roma; endemic official corruption; law enforcement authorities condoning violence against women and girls; and abuse against institutionalized persons with disabilities. The judiciary took steps to prosecute and punish officials who committed abuses, but authorities did not have effective mechanisms to do so and delayed proceedings involving alleged police abuse and corruption, with the result that many of the cases ended in acquittals. Impunity for perpetrators of human rights abuses was a continuing problem. Section 1. Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from: a. -

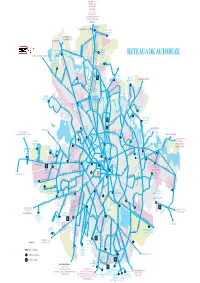

Autobuze.Pdf

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 261 BANEASA RETEAUA DE AUTOBUZE 204 205 304 Sisesti 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 112 205 261 COMPLEX 131 261301 Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti COMERCIAL CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucu Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 COLOSSEUM 203 335 361 605 780 783 Bd.R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 112 Aerogarii R402 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 restii Noi DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 331 R436 CFR 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 112 135 243 Str. Jiului Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Sos. Chitilei 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Poligrafiei 231 243 Str. Peris 780 783 331 PIATA Str.Oi 243 382 Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 243 382 R447PRESEI R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 243 131 203 205 261 304 135 343 105 203 231 tuz CARTIER 261 304 330 361 605 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 Bd. Marasti GIULESTI-SARBI 162 R441 R442 R443 r a lo c i s Bd. Expozitiei231 330 r o a dronache 162 163 105 780 R444 R446t e R409 243 343 Str. Sportului a r 105 i CLABUCET R447 o v l F 381 R448 A . -

City of Bucharest

City of Bucharest Intercultural Profile 1. Background1 Bucharest is the capital and largest city, as well as the cultural, industrial, and financial centre of Romania. According to the 2011 census, 1,883,425 inhabitants live within the city limits, a decrease from the 2002 census. Taking account of the satellite towns around the urban area, the proposed metropolitan area of Bucharest would have a population of 2.27 million people. However, according to unofficial data given by Wikipedia, the population is more than 3 million (raising a point that will be reiterated throughout this report that statistics are not universally reliable in Romania).Notwithstanding, Bucharest is the 6th largest city in the European Union by population within city limits, after London, Berlin, Madrid, Rome, and Paris. Bucharest accounts for around 23% of the country’s GDP and about one-quarter of its industrial production, while being inhabited by only 10% of the country’s population. In 2010, at purchasing power parity, Bucharest had a per-capita GDP of EUR 14,300, or 45% that of the European Union average and more than twice the Romanian average. Bucharest’s economy is mainly focused on industry and services, with a significant IT services sector. It houses 186,000 companies, and numerous companies have set up headquarters in Bucharest, attracted by the highly skilled labour force and low operating costs. The list includes multinationals such as Microsoft, IBM, P&G, HP, Oracle, Wipro, and S&T. In terms of higher education, Bucharest is the largest Romanian academic centre and one of the most important locales in Eastern Europe, with 16 public and 18 private institutes and over 300,00 students. -

Residential Areas with Deficient Access to Urban Parks in Bucharest – Priority Areas for Urban Rehabilitation

ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS and DEVELOPMENT Residential areas with deficient access to urban parks in Bucharest – priority areas for urban rehabilitation CRISTIAN IOJA, MARIA PATROESCU, LIDIA NICULITA, GABRIELA PAVELESCU, MIHAI NITA, ANNEMARIE IOJA Centre for Environmental Research and Impact Studies, University of Bucharest 1 Nicolae Balcescu Blvd., Sector 1, Bucharest, ROMANIA Abstract: - The paper emphasizes the real dimension of the urban parks surfaces deficit upon the built environment in Bucharest city. There were established residential area categories with deficient access to urban parks of high quality, considered to be priority intervention areas for urban rehabilitation (residential areas situated at more than 3 km from municipal importance parks, at more than 1 km from urban parks, residential areas with access to crowded parks, or with access to parks that have degraded endowments). Deficient access to Bucharest urban parks was correlated with the development projects of new residential quarters, being obviously the tendency of city suffocation under the pressure of constructed surfaces and agglomeration. Key-Words: - urban parks, residential areas, housing, Bucharest, rehabilitation priorities areas 1 Introduction residential areas was completed by a tendency of Green spaces represent an essential component in vertical development, initially through 4 floors large urban environments, to which they offer constru-ctions, then 9 and 10 floors, in the present numerous direct and indirect services (improving reaching 20 floors. These new residential surfaces environmental quality, recreation and leisure, accentuated the real deficit of public green spaces. climate amelioration etc.) [1], [2], [3]. Green spaces deficit is expressed through the degradation of housing conditions in urban environments [1], [2], [3], automatically determining an increase of housing costs [4], a degradation of the population’s health state [5], [6] and the appearance of social segregation problems [7], [8]. -

A Proposal for a New Administrative-Territorial Outline of Bucharest-Based In-City Discontinuities

DOI:10.24193/tras.56E.5 Published First Online: 02/28/2019 A PROPOSAL FOR A NEW ADMINISTRATIVE-TERRITORIAL OUTLINE OF BUCHAREST-BASED IN-CITY DISCONTINUITIES Radu SĂGEATĂ Radu SĂGEATĂ Researcher, Institute of Geography, Romanian Academy, Bucharest, Romania Tel.: 0040-213-135.990 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Urban development represents a perma- nent challenge for space organization in large cities. Space organization is to be achieved by observing the homogeneity and specifi city of dwelling cores (urban quarters) as premises for urban structure functionality and viability. The administrative boundaries should overlap discontinuity areas in the city, which cause di- vergent population fl ows. The radial-concentric type morphostructure of Bucharest, Romania’s capital-city, is based on the sectorial model of six administrative sectors, in this case. Each sec- tor has both central and peripheral zones, with sharper inter-sectorial than intra-sectorial dispar- ities. Massive industrialization and urbanization in the socialist period led to the development of the housing stock and the individualization of quarter centers as secondary polarization cores in the city. This situation calls for revisiting the current administrative boundaries in the light of city discontinuities and establishing some multi- core sectors by encompassing homogeneous quarters in terms of functionality, specifi city, and social-urbanistic problems, so that administra- tive and local development policies could better match the concrete situations on the ground. Keywords: urban morphostructure, admin- istrative sectors, quarter centers, discontinuities, functionality, Bucharest. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 77 No. 56 E/2019 pp. 77-96 1. Introduction. Targets Urban expansion calls for an ever more complex management of city areas. -

Intra-Urban Spatial Changes Among Women Entrepreneurs in Bucharest (Romania) During Economic Transition (1992-2002)

Journal of Urban and Regional Analysis, vol. VIII, 1, 2016, p. 37 - 46 INTRA-URBAN SPATIAL CHANGES AMONG WOMEN ENTREPRENEURS IN BUCHAREST (ROMANIA) DURING ECONOMIC TRANSITION (1992-2002) Audrey KOBAYASHI*, Alexandru GAVRIȘ **, Ioan IANOȘ*** *Queen’s University, Canada **Bucharest University of Economic Studies, Romania ***University of Bucharest, Interdisciplinary Centre for Advanced Research on Territorial Dynamics, Romania Abstract: Women entrepreneurs in Bucharest, Romania, increased by six times (compared to five times for men) between the 1992 and 2002 censuses, during a period of transition from a centrally planned to a market economy. A study of over 150 territory referential units shows a concentration of business women in central, high income areas and a correlation between the entrepreneurial status and education. Data from 50 telephone interviews show that women with university degrees are more likely to operate at a city-wide or national scale, in fields such as cosmeticology, consultancy, law, design, art, and manufacturing. Women without higher education tend to operate at a local, smaller scale. Both spatial concentration and education have an impact upon business behaviour. Key Words: women entrepreneurs, transition economy, post-socialism, Bucharest Introduction The study of the spatial implications of women’s work has been a growing topic in geography and other social sciences since the 1970s (Gamarnikow 1978). Most studies adopt a sectoral approach to address the characteristics of women business owners (demographic, education and training, work experience, competencies), or market sectors, including investment fields. Since the 1980s, geographers have addressed the interconnections of gender, work, and urban processes such as gentrification (Wekerle 1984, Rose 1987) and urban economic restructuring (Mackenzie 1986, England 1991).