Bucharest. Geographical and Geopolitical Considerations1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anexe La H.C.G.M.B. Nr. 254 / 2008

NR. FELUL LIMITE DENUMIREA SECTOR CRT. ARTEREI DELA ..... PANA LA ..... 0 1 2 3 4 5 1 Bd. Aerogarii Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti Bd. Ficusului 1 2 Str. Avionului Sos. Pipera Linie CF Constanta 1 3 Bd. Averescu Alex. Maresal Bd. Ion Mihalache Sos. Kiseleff 1 4 Bd. Aviatorilor Pta Victoriei Sos. Nordului 1 5 P-ta Aviatorilor 1 6 Str. Baiculesti Sos. Straulesti Str. Hrisovului 1 7 Bd. Balcescu Nicolae Bd. Regina Elisabeta Str. CA Rosetti 1 8 Str. Baldovin Parcalabul Str. Mircea Vulcanescu Str. Cameliei .(J' 9 Bd. Banu Manta Sos. Nicolae Titulescu Bd. Ion Mihalache /'co 1 ~,..~:~':~~~.~. (;~ 10 Str. Beller Radu It. avo Calea Dorobanti Bd. Mircea Eliade ,i: 1 :"~," ~, ',.." " .., Str. Berzei ,;, 1 t~:~~:;:lf~\~l'~- . ~: 11 Str. Berthelot Henri Mathias, G-ral Calea Victoriei .. ~!- .~:,.-::~ ",", .\ 1.~ 12 P-ta Botescu Haralambie ~ . 13 Str. Berzei Calea Plevnei Calea Grivitei 1 ~; 14 Str. Biharia Bd. Aerogarii Str. Zapada Mieilor 1 15 Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti P-ta Presei Libere Str. Elena Vacarescu 1 16 Sos. Bucuresti Targoviste Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos.Odaii 1 17 Bd. Bucurestii Noi Calea Grivitei Sos. Bucurestii Targoviste 1 18 Str. Budisteanu Ion Str. G-ral Berthelot Calea Grivitei 1 19 Str. Buzesti Calea Grivitei P-ta Victoriei 1 20 P-ta Buzesti 1 21 Str. Campineanu Ion Str. Stirbei Voda Bd. Nicolae Balcescu 1 22 Str. Caraiman Calea Grivitei Bd. Ion Mihalache 1 23 Str. Caramfil Nicolae Sos. Nordului Str. Av. AI. Serbanescu 1 24 Bd. Campul Pipera Aleea Privighetorilor 1 25 P-ta Charles de Gaulle -'- 1 26 Sos. Chitilei ,.".ll·!A Bd. Bucurestii Noi Limita administrativa - 1 27 Str. -

Historical GIS: Mapping the Bucharest Geographies of the Pre-Socialist Industry Gabriel Simion*, Alina Mareci, Florin Zaharia, Radu Dumitru

# Gabriel Simion et al. Human Geographies – Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography Vol. 10, No. 2, November 2016 | www.humangeographies.org.ro ISSN–print: 1843–6587 | ISSN–online: 2067–2284 Historical GIS: mapping the Bucharest geographies of the pre-socialist industry Gabriel Simion*, Alina Mareci, Florin Zaharia, Radu Dumitru University of Bucharest, Romania This article aims to map the manner in which the rst industrial units crystalized in Bucharest and their subsequent dynamic. Another phenomenon considered was the way industrial sites grew and propagated and how the rst industrial clusters formed, thus amplifying the functional variety of the city. The analysis was undertaken using Historical GIS, which allowed to integrate elements of industrial history with the location of the most important industrial objectives. Working in GIS meant creating a database with the existing factories in Bucharest, but also those that had existed in different periods. Integrating the historical with the spatial information about industry in Bucharest was preceded by thorough preparations, which included geo-referencing sources (city plans and old maps) and rectifying them. This research intends to serve as an example of how integrating past and present spatial data allows for the analysis of an already concluded phenomenon and also explains why certain present elements got to their current state.. Key Words: historical GIS, GIS dataset, Bucharest. Article Info: Received: September 5, 2016; Revised: October 24, 2016; Accepted: November 15, 2016; Online: November 30, 2016. Introduction The spatial evolution of cities starting with the ending of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th is closely connected to their industrial development. -

Braşov Highway on the Economic and Functional Structure of Human Settlements

ROMANIAN REVIEW OF REGIONAL STUDIES, Volume VII, Number 1, 2011 FORECAST FOR THE IMPACT OF BUCHAREST – BRA ŞOV HIGHWAY ON THE ECONOMIC AND FUNCTIONAL STRUCTURE 1 OF HUMAN SETTLEMENTS IN ILFOV COUNTY CĂTĂLINA CÂRSTEA 2, FLORENTINA ION 3, PETRONELA NOV ĂCESCU 4 ABSTRACT - One of the most publicized issues concerning the infrastructure of Romania is the Bucharest-Bra şov highway. The long-awaited project aims to streamline the traffic between the Capital and the central part of the country, representing the central area of the Pan - European Road Corridor IV. The length of the highway on the territory of Ilfov County is 31 km, representing 17% of the total length of Bucharest- Bra şov highway. The start of the highway will have strong effects on economic structure and on the way the Bucharest Metropolitan Area will work. We can expect an increase in the disparities between the settlements of Ilfov County. This pattern is also observable on the Bucharest- Ploie şti corridor where, in recent years, much of the Ilfov county's economic activities have migrated to the north, especially along that corridor. Besides economic migration, intense residential migration followed the Bucharest – Ploie şti corridor, residents of the Bucharest itself moving out to the north of Ilfov County. Probably, the future Bucharest – Bra şov highway will lead to an increased suburbanization and periurbanization, this in turn giving way to the crowding of the area by businesses eager to have access to the highway. This project will likely increase the gap between north and south of Ilfov County. In addition to changes that may occur at the county level, changes will also have an impact on the localities themselves since the areas located near the highway will have an economic and demographic growth rate superior to more remote areas. -

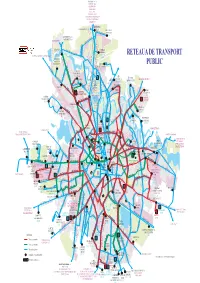

RETEA GENERALA 01.07.2021.Cdr

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 97 204 205 304 261 Sisesti BANEASA RETEAUA DE TRANSPORT R402 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 COMPLEX 112 205 261 97 131 261301 COMERCIAL Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti PUBLIC COLOSSEUM CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 203 335 361 605 780 783 112 R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 Bd. Aerogarii R402 97 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 24 331R436 CFR Str. Alex. Serbanescu 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 DRIDU Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 65 86 112 135 243 Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Bd. Gloriei24 Str. Jiului 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Sos. Chitilei Poligrafiei PIATA PLATFORMA Bd. BucurestiiPajurei Noi 231 243 Str. Peris MEZES 780 783 INDUSTRIALA Str. PRESEI Str.Oi 3 45 65 86 331 243 3 45 382 PASAJ Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 3 41 243 PIPERA 382 DEPOUL R447 R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 i 65 86 97 243 16 36 COLENTINA 131105 203 205 261203 304 231 261 304 330 135 343 n tuz BUCURESTII NOI a R441 R442 R443 c 21 i CARTIER 605 tr 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 DEPOUL Bd. -

Data on Cerambycidae and Chrysomelidae (Coleoptera: Chrysomeloidea) from Bucureªti and Surroundings

Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle © Novembre Vol. LI pp. 387–416 «Grigore Antipa» 2008 DATA ON CERAMBYCIDAE AND CHRYSOMELIDAE (COLEOPTERA: CHRYSOMELOIDEA) FROM BUCUREªTI AND SURROUNDINGS RODICA SERAFIM, SANDA MAICAN Abstract. The paper presents a synthesis of the data refering to the presence of cerambycids and chrysomelids species of Bucharest and its surroundings, basing on bibliographical sources and the study of the collection material. A number of 365 species of superfamily Chrysomeloidea (140 cerambycids and 225 chrysomelids species), belonging to 125 genera of 16 subfamilies are listed. The species Chlorophorus herbstii, Clytus lama, Cortodera femorata, Phytoecia caerulea, Lema cyanella, Chrysolina varians, Phaedon cochleariae, Phyllotreta undulata, Cassida prasina and Cassida vittata are reported for the first time in this area. Résumé. Ce travail présente une synthèse des données concernant la présence des espèces de cerambycides et de chrysomelides de Bucarest et de ses environs, la base en étant les sources bibliographiques ainsi que l’étude du matériel existant dans les collections du musée. La liste comprend 365 espèces appartenant à la supra-famille des Chrysomeloidea (140 espèces de cerambycides et 225 espèces de chrysomelides), encadrées en 125 genres et 16 sous-familles. Les espèces Chlorophorus herbstii, Clytus lama, Cortodera femorata, Phytoecia caerulea, Lema cyanella, Chrysolina varians, Phaedon cochleariae, Phyllotreta undulata, Cassida prasina et Cassida vittata sont mentionnées pour la première fois dans cette zone Key words: Coleoptera, Chrysomeloidea, Cerambycidae, Chrysomelidae, Bucureºti (Bucharest) and surrounding areas. INTRODUCTION Data on the distribution of the cerambycids and chrysomelids species in Bucureºti (Bucharest) and the surrounding areas were published beginning with the end of the 19th century by: Jaquet (1898 a, b, 1899 a, b, 1900 a, b, 1901, 1902), Montandon (1880, 1906, 1908), Hurmuzachi (1901, 1902, 1904), Fleck (1905 a, b), Manolache (1930), Panin (1941, 1944), Eliescu et al. -

People's Advocate

European Network of Ombudsmen THE 2014 REPORT OF PEOPLE’S ADVOCATE INSTITUTION - SUMMARY - In accordance with the provisions of art. 60 of the Constitution and those of art. 5 of Law no. 35/1997 on the organization and functioning of the People's Advocate Institution, republished, with subsequent amendments, the Annual Report concerning the activity of the institution for one calendar year is submitted by the People's Advocate, until the 1st of February of the following year, to Parliament for its debate in the joint sitting of the two Chambers. We present below a summary of the 2014 Report of the People’s Advocate Institution, which has been submitted to Parliament, within the legal deadline provided by Law no. 35/1997. GENERAL VOLUME OF ACTIVITY The overview of the activity in 2014 can be summarized in the following statistics: - 16,841 audiences , in which violations of individuals' rights have been alleged, out of which 2,033 at the headquarters and 14,808 at the territorial offices; - 10,346 complaints registered at the People's Advocate Institution, out of which 6,932 at the headquarters and 3,414 at the territorial offices; Of these, a total of 7,703 complaints were sent to the People's Advocate on paper, 2,551 by email, and 92 were received from abroad. - 8,194 calls recorded by the dispatcher service, out of which 2,504 at the headquarters and 5,690 at the territorial offices; - 137 investigations conducted by the People's Advocate Institution, out of which 33 at the headquarters and 104 at the regional offices; - 56 ex officio -

Lista Unităţilor Scolare Din Judeţul Giurgiu Si Circumscriptiile Arondate

LISTA UNIT ĂŢ ILOR SCOLARE DIN JUDE ŢUL GIURGIU SI CIRCUMSCRIPTIILE ARONDATE PENTRU RECENSAMANTUL COPIILOR IN VEDEREA INSCRIERII IN CLASA PREGATITOARE/CLASA I Pentru anul şcolar 2012/2013 Nr. Localitatea Denumire scoala Cicumscriptii recensamant crt. Com./ oras 1. Adunatii Sc.I-VIII Ad.Copaceni* Comuna Aduna ţii Cop ăceni, Sat Mogo şeşti Sat Varlaam Copaceni Sc.I-VIII Darasti Sat D ărăş ti, comuna Aduna ţii Cop ăceni, 2. Baneasa Sc.I-VIII Baneasa* Comuna B ăneasa, Sc.I-IV Frasinu Sat Frasinu, comuna B ăneasa, Sc.I-IV Meletie Sat Meletie, comuna B ăneasa, Sc.I-VIII Pietrele Sat Pietrele, comuna B ăneasa, Grad.Sf. Gheorghe Sat Sf. Gheorghe, comuna B ăneasa, Sc.I-IV Baneasa Comuna B ăneasa, 3. Bolintin Sc.I-VIII Bolintin Deal* Comuna Bolintin Deal, Deal Sc.I-VIII Mihai Voda Sat Mihai Vod ă, comuna Bolintin Deal, 4. Bolintin Sc.I-VIII Bolintin Vale* Ora ş Bolintin Vale, Vale Sc.I-VIII Malu Spart Sat Malu Spart, Sc.I-IV Suseni Sat Suseni 5. Buturugeni Sc.I-VIII Buturugeni* Comuna Buturugeni, Sc.I-VIII Padureni Sat P ădureni, comuna Buturugeni, Sc.I-IV Prisiceni Sat Prisiceni, comuna Buturugeni, Sc.I-IV Posta Sat Po şta, comuna Buturugeni, 6. Bucsani Sc.I-VIII Bucsani* Comuna Buc şani, Sc.I-VIII Vadu Lat Sat Vadu Lat, comuna Buc şani, Sc.I-IV Uiesti Sat Uie şti, comuna Buc şani, Sc.I-IV Podisor Sat Podi şor, comuna Buc şani, Sc.I-IV Goleasca Sat Goleasca, comuna Buc şani, 7. Bulbucata Sc.I-VIII Bulbucata* Comuna Bulbucata, 8. -

LIST of HOSPITALS, CLINICS and PHYSICIANS with PRIVATE PRACTICE in ROMANIA Updated 04/2017

LIST OF HOSPITALS, CLINICS AND PHYSICIANS WITH PRIVATE PRACTICE IN ROMANIA Updated 04/2017 DISCLAIMER: The U.S. Embassy Bucharest, Romania assumes no responsibility or liability for the professional ability or reputation of, or the quality of services provided by the medical professionals, medical facilities or air ambulance services whose names appear on the following lists. Names are listed alphabetically, and the order in which they appear has no other significance. Professional credentials and areas of expertise are provided directly by the medical professional, medical facility or air ambulance service. When calling from overseas, please dial the country code for Romania before the telephone number (+4). Please note that 112 is the emergency telephone number that can be dialed free of charge from any telephone or any mobile phone in order to reach emergency services (Ambulances, Fire & Rescue Service and the Police) in Romania as well as other countries of the European Union. We urge you to set up an ICE (In Case of Emergency) contact or note on your mobile phone or other portable electronics (such as Ipods), to enable first responders to get in touch with the person(s) you designated as your emergency contact(s). BUCHAREST Ambulance Services: 112 Private Ambulances SANADOR Ambulance: 021-9699 SOS Ambulance: 021-9761 BIOMEDICA Ambulance: 031-9101 State Hospitals: EMERGENCY HOSPITAL "FLOREASCA" (SPITALUL DE URGENTA "FLOREASCA") Calea Floreasca nr. 8, sector 1, Bucharest 014461 Tel: 021-599-2300 or 021-599-2308, Emergency line: 021-962 Fax: 021-599-2257 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.urgentafloreasca.ro Medical Director: Dr. -

Download This PDF File

THE SOCIO-SPATIAL DIMENSION OF THE BUCHAREST GHETTOS Viorel MIONEL Silviu NEGUŢ Viorel MIONEL Assistant Professor, Department of Economics History and Geography, Faculty of International Business and Economics, Academy of Economic Studies, Bucharest, Romania Tel.: 0040-213-191.900 Email: [email protected] Abstract Based on a socio-spatial analysis, this paper aims at drawing the authorities’ attention on a few Bucharest ghettos that occurred after the 1990s. Silviu NEGUŢ After the Revolution, Bucharest has undergone Professor, Department of Economics History and Geography, many socio-spatial changes. The modifications Faculty of International Business and Economics, Academy of that occurred in the urban perimeter manifested Economic Studies Bucharest, Romania in the technical and urban dynamics, in the urban Tel.: 0040-213-191.900 infrastructure, and in the socio-economic field. The Email: [email protected] dynamics and the urban evolution of Bucharest have affected the community life, especially the community homogeneity intensely desired during the communist regime by the occurrence of socially marginalized spaces or ghettos as their own inhabitants call them. Ghettos represent an urban stain of color, a special morphologic framework. The Bucharest “ghettos” appeared by a spatial concentration of Roma population and of poverty in zones with a precarious infrastructure. The inhabitants of these areas (Zăbrăuţi, Aleea Livezilor, Iacob Andrei, Amurgului and Valea Cascadelor) are somehow constrained to live in such spaces, mainly because of lack of income, education and because of their low professional qualification. These weak points or handicaps exclude the ghetto population from social participation and from getting access to urban zones with good habitations. -

Waste Management in the Ilfov County

Results of the Transferability Study for the Implementation of the “LET’S DO IT WITH FERDA” Good Practice in the Ilfov County Brussels, 7 November 2012 Communication and education Workshop This project is cofinanced by the ERDF and made possible by the INTERREG IVC programme 1 WASTE PREVENTION IN ROMANIA • The National Waste Management Strategy and Plan the basic instruments that ensure the implementation of the EU waste management policy in Romania. • The National Waste Management Plan and Strategy cover all the types of waste (municipal and production) and establish four groups of objectives: – overall strategic objectives for waste management; – strategic objectives for specific waste streams (agricultural waste, waste from the production of heat and electricity, incineration and co- incineration, construction and demolition waste, waste from treatment plants, biodegradable waste, packaging waste, used tires, end of life vehicles (ELV), waste electrical and electronic equipment (DEEE)); – overall strategic objectives for the management of hazardous waste; – strategic objectives for specific hazardous waste streams. This project is cofinanced by the ERDF and made possible by the INTERREG IVC programme 2 WASTE PREVENTION IN ROMANIA (2) – SOP ENVIRONMENT • The overall objective of Sectorial Operational Program ENVIRONMENT to "protect and improve the environment and quality of life in Romania, focusing in particular on observing the environmental acquis". • A specific goal the "development of sustainable waste management systems by -

Visual Approach Chart (07 NOV 2019)

AIP AD 2.5-40 ROMANIA 07 NOV 2019 OT OPENI T W R 118.805 BU CU R ES T I VOLM ET 126.800 BU CU R ES T I APPR OACH 119.415 44˚ 34' 16" N OT OPENI T W R ALT N 120.900 VISUAL APPROACH CHART - ICAO ELEV 314 FT BU CU R ES T I APPR OACH ALT N 120.600 026˚ 05' 06" E OT OPENI GND 121.855 BUCURESTI/ OT OPENI GND ALT N 121.700 BU CU R ES T I DIR ECT OR 127.155 Henri Coanda (LROP) OT OPENI AT IS 118.500 BU CU R ES T I DIR ECT OR ALT N 120.600 Aircra ft ca tegories A a n d H Puchen ii BU CU R ES T I INFOR M AT ION 129.400 25°40'E 25°50'E 26°E 26°10'E 26°20'E 26°30'E M a ri Pa la n ca S a lciile BU CU R ES T Va rn ita Viiso L. Ghighiu I T M Puchen ii-M osn en i a ra V A 1 A M a rcesti BU FL A Gheb oa ia CU R E 175 - roa ga S T I T 4500 S irn a Va Predesti R M A 2 FT QN T oti N A F H Posta rn a cu L1 5 Ba len i-R om a n i 75 - 2 000FT ˚ QN M irosla vesti ELEV, ALT , HEIGHT S IN FEET Fin ta M a re Fra sin u H Fa n a ri 2 Bechin esti Cristea sca Gherghita 0 L. -

1 Circumscripţii Sanitare Veterinare De Asistenţă

Circumscripţii Sanitare Veterinare de Asistenţă Date contact medici veterinari Nr CSV Contractant Medic veterinar Date de contact crt 1 Adunatii Copaceni VET CONSULT SRL 2 Colibasi ECO HORTI VET SRL Dr Petre Stelu 0722 526 419 3 Comana VET CONSULT SRL 4 Gostinari ECO HORTI VET SRL 5 Baneasa CMV DUMITRESCU CRISTIAN DAN Dr.Dumitrescu Cristian 0723 688 184 6 Fratesti TOP LEXUS IMPORT EXPORT SRL Dr Capris Vasilica 0728 907 306 7 Bolintin Deal DRASIMAR VET SRL Dr Dragne Vasile 0740 197 762 8 Bolintin Vale 9 Gaiseni CMV DUTESCU MIHAIL Dr Dutescu Mihail 0721 264 218 10 Floresti Stoenesti 11 Bucsani CMV DRAGOICEA GHEORGHE Dr Dragoicea Gheorghe 0721 107 339 12 Bulbucata VSP VET SRL Dr Viespe Constantin 0744 548 061 13 Mihailesti 14 Buturugeni CMV DOGARU MARIUS Dr Dogaru Marius 0723 265 633 15 Gradinari 16 Calugareni CMV IRIMIE GABRIEL Dr Irimie Gabriel 0766 450 187 17 Stoenesti 18 Clejani CMV TUDOR STELICA Dr Tudor Stelica 0723 533 212 19 Crevedia Mare IORDACHE MIHAITA VETERINAR SRL Dr Iordache Mihaita 0727 886 453 20 Marsa AMEDEA ANISIA VET SRL Dr Masalan Catalin 0743 162 642 21 Daia ALPHA VET SRL Dr Tepus Marius 0766 522 339 22 Gogosari 23 Gaujani CMV BURCEA GABRIEL Dr Burcea Gabriel 0723 488 022 24 Ghimpati CMV VASILE CONSTANTIN Dr Vasile Constantin 0722 399 922 25 Schitu 26 Gostinu CMV PATRASCU TEODOR Dr Patrascu Teodor 0722 88 22 44 27 Oinacu 28 Greaca CMV COSTACHE VASILE Dr Costache Vasile 0723 375 278 29 Hotarele 30 Iepuresti ALD MED VET SRL Dr Dan Marin Alexandru 0723 782 176 31 Joita Dr Pana Daniel 0722 400 950 32 Letca Noua CMV TUDOR