City of Bucharest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Practical Guide for Police Services to Prevent Discrimination Against the Roma Communities

Practical Guide for Police services to prevent discrimination against the Roma communities With financial supportUnión from Europea the Fundamental Rights and Fondo Social Europeo Citizenship Programme of the European Union Project Code Number: JUST/2012/FRAC/AG/2848 Practical Guide for Police services to prevent discrimination against the Roma communities With financial supportUnión from Europea the Fundamental Rights and Fondo Social Europeo Citizenship Programme of the European Union Project Code Number: JUST/2012/FRAC/AG/2848 Title: Practical guide for police services to prevent discrimination against the Roma communities Drafted by: Javier Sáez (Fundación Secretariado Gitano) Sara Giménez (Fundación Secretariado Gitano) Date: July 2014 Note: this Guide has been drafted with the advice of David Martín Abánades, Police Sergeant- Head of the Team for the Police Management of Diversity of the Local Police of Fuenlabrada and José Fco. Cano, President of the National Union of Chief Constables and Directors of Local Police (Unijepol, Spain). Disclaimer: This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This pub- lication reflects only the views of the authors and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Layout and printing: Pardedós. 2 Practical Guide for police services to prevent discrimination against the Roma communities Summary Introduction .....................................................................................5 1. The current situation: -

Trials of the War Criminals

TRIALS OF THE WAR CRIMINALS General Considerations The Fascist regime that ruled Romania between September 14, 1940, and August 23, 1944, was brought to justice in Bucharest in May 1946, and after a short trial, its principal leaders—Ion and Mihai Antonescu and two of their closest assistants—were executed, while others were sentenced to life imprisonment or long terms of detention. At that time, the trial’s verdicts seemed inevitable, as they indeed do today, derived inexorably from the defendants’ decisions and actions. The People’s Tribunals functioned for a short time only. They were disbanded on June 28, 1946,1 although some of the sentences were not pronounced until sometime later. Some 2,700 cases of suspected war criminals were examined by a commission formed of “public prosecutors,”2 but only in about half of the examined cases did the commission find sufficient evidence to prosecute, and only 668 were sentenced, many in absentia.3 There were two tribunals, one in Bucharest and one in Cluj. It is worth mentioning that the Bucharest tribunal sentenced only 187 people.4 The rest were sentenced by the tribunal in Cluj. One must also note that, in general, harsher sentences were pronounced by the Cluj tribunal (set up on June 22, 1 Marcel-Dumitru Ciucă, “Introducere” in Procesul maresalului Antonescu (Bucharest: Saeculum and Europa Nova, 1995-98), vol. 1: p. 33. 2 The public prosecutors were named by communist Minister of Justice Lucret iu Pătrăşcanu and most, if not all of them were loyal party members, some of whom were also Jews. -

Anexe La H.C.G.M.B. Nr. 254 / 2008

NR. FELUL LIMITE DENUMIREA SECTOR CRT. ARTEREI DELA ..... PANA LA ..... 0 1 2 3 4 5 1 Bd. Aerogarii Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti Bd. Ficusului 1 2 Str. Avionului Sos. Pipera Linie CF Constanta 1 3 Bd. Averescu Alex. Maresal Bd. Ion Mihalache Sos. Kiseleff 1 4 Bd. Aviatorilor Pta Victoriei Sos. Nordului 1 5 P-ta Aviatorilor 1 6 Str. Baiculesti Sos. Straulesti Str. Hrisovului 1 7 Bd. Balcescu Nicolae Bd. Regina Elisabeta Str. CA Rosetti 1 8 Str. Baldovin Parcalabul Str. Mircea Vulcanescu Str. Cameliei .(J' 9 Bd. Banu Manta Sos. Nicolae Titulescu Bd. Ion Mihalache /'co 1 ~,..~:~':~~~.~. (;~ 10 Str. Beller Radu It. avo Calea Dorobanti Bd. Mircea Eliade ,i: 1 :"~," ~, ',.." " .., Str. Berzei ,;, 1 t~:~~:;:lf~\~l'~- . ~: 11 Str. Berthelot Henri Mathias, G-ral Calea Victoriei .. ~!- .~:,.-::~ ",", .\ 1.~ 12 P-ta Botescu Haralambie ~ . 13 Str. Berzei Calea Plevnei Calea Grivitei 1 ~; 14 Str. Biharia Bd. Aerogarii Str. Zapada Mieilor 1 15 Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti P-ta Presei Libere Str. Elena Vacarescu 1 16 Sos. Bucuresti Targoviste Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos.Odaii 1 17 Bd. Bucurestii Noi Calea Grivitei Sos. Bucurestii Targoviste 1 18 Str. Budisteanu Ion Str. G-ral Berthelot Calea Grivitei 1 19 Str. Buzesti Calea Grivitei P-ta Victoriei 1 20 P-ta Buzesti 1 21 Str. Campineanu Ion Str. Stirbei Voda Bd. Nicolae Balcescu 1 22 Str. Caraiman Calea Grivitei Bd. Ion Mihalache 1 23 Str. Caramfil Nicolae Sos. Nordului Str. Av. AI. Serbanescu 1 24 Bd. Campul Pipera Aleea Privighetorilor 1 25 P-ta Charles de Gaulle -'- 1 26 Sos. Chitilei ,.".ll·!A Bd. Bucurestii Noi Limita administrativa - 1 27 Str. -

Budapest to Bucharest Danube River Cruise

BUDAPEST TO BUCHAREST DANUBE Program Guide RIVER CRUISE August 20-29, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Before You Go ....................................................... 3-4 Getting There ......................................................... 5-6 Program Information .............................................. 7-9 Omissions Waiver .................................................. 9 Amenities & Services ............................................. 10-12 Frequently Asked Questions .................................. 13-14 Itinerary .................................................................. 15-16 BEFORE YOU GO PERSONAL TRAVEL DOCUMENTS Passport: A passport that is valid for at least six (6) months after your return date is required for this program. Visas: U.S. and Canadian citizens do not need visas for countries visited. Other nationalities should consult the local embassies or consulates for visa requirements. All documentation required for this itinerary is the sole responsibility of the guest. Brand g will not be responsible for advising and/or obtaining required travel documentation for any passenger, or for any delays, damages, and/or losses, including missed portions of your trip, related to improper or absent travel documentation. It is suggested that copies of important documents, including your passport and visas, be kept in a separate place, in case the originals are lost or stolen. Travel Protection: While travel insurance is not required to participate in this program, Brand g strongly recommends that each guest purchase -

Generated an Epistemological Knowledge of the Nation—Quantifying And

H-Nationalism The “Majority Question” in Interwar Romania: Making Majorities from Minorities in a Heterogeneous State Discussion published by Emmanuel Dalle Mulle on Wednesday, April 22, 2020 H-Nationalism is proud to publish here the sixth post of its “Minorities in Contemporary and Historical Perspectives” series, which looks at majority- minority relations from a multi-disciplinary and diachronic angle. Today’s contribution, by R. Chris Davis (Lone Star College–Kingwood), examines the efforts of Romanian nation-builders to make Romanians during the interwar period. Heterogeneity in Interwar Romania While the situation of ethnic minorities in Romania has been examined extensively within the scholarship on the interwar period, far too little consideration is given into the making of the Romanian ethnic majority itself. My reframing of the “minority question” into its corollary, the “majority question,” in this blogpost draws on my recently published book examining the contested identity of the Moldavian Csangos, an ethnically fluid community of Romanian- and Hungarian-speaking Roman Catholics in eastern Romania.[1] While investigating this case study of a putative ethnic, linguistic, and religious minority, I was constantly reminded that not only minorities but also majorities are socially constructed, crafted from regional, religious, and linguistic bodies and identities. Transylvanians, Bessarabians, and Bănățeni (people from the Banat region) and Regațeni (inhabitants of Romania’s Old Kingdom), for example, were rendered into something -

Historical GIS: Mapping the Bucharest Geographies of the Pre-Socialist Industry Gabriel Simion*, Alina Mareci, Florin Zaharia, Radu Dumitru

# Gabriel Simion et al. Human Geographies – Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography Vol. 10, No. 2, November 2016 | www.humangeographies.org.ro ISSN–print: 1843–6587 | ISSN–online: 2067–2284 Historical GIS: mapping the Bucharest geographies of the pre-socialist industry Gabriel Simion*, Alina Mareci, Florin Zaharia, Radu Dumitru University of Bucharest, Romania This article aims to map the manner in which the rst industrial units crystalized in Bucharest and their subsequent dynamic. Another phenomenon considered was the way industrial sites grew and propagated and how the rst industrial clusters formed, thus amplifying the functional variety of the city. The analysis was undertaken using Historical GIS, which allowed to integrate elements of industrial history with the location of the most important industrial objectives. Working in GIS meant creating a database with the existing factories in Bucharest, but also those that had existed in different periods. Integrating the historical with the spatial information about industry in Bucharest was preceded by thorough preparations, which included geo-referencing sources (city plans and old maps) and rectifying them. This research intends to serve as an example of how integrating past and present spatial data allows for the analysis of an already concluded phenomenon and also explains why certain present elements got to their current state.. Key Words: historical GIS, GIS dataset, Bucharest. Article Info: Received: September 5, 2016; Revised: October 24, 2016; Accepted: November 15, 2016; Online: November 30, 2016. Introduction The spatial evolution of cities starting with the ending of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th is closely connected to their industrial development. -

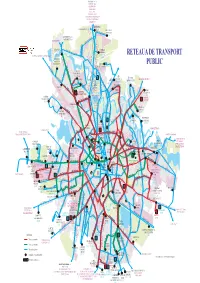

RETEA GENERALA 01.07.2021.Cdr

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 97 204 205 304 261 Sisesti BANEASA RETEAUA DE TRANSPORT R402 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 COMPLEX 112 205 261 97 131 261301 COMERCIAL Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti PUBLIC COLOSSEUM CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 203 335 361 605 780 783 112 R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 Bd. Aerogarii R402 97 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 24 331R436 CFR Str. Alex. Serbanescu 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 DRIDU Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 65 86 112 135 243 Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Bd. Gloriei24 Str. Jiului 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Sos. Chitilei Poligrafiei PIATA PLATFORMA Bd. BucurestiiPajurei Noi 231 243 Str. Peris MEZES 780 783 INDUSTRIALA Str. PRESEI Str.Oi 3 45 65 86 331 243 3 45 382 PASAJ Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 3 41 243 PIPERA 382 DEPOUL R447 R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 i 65 86 97 243 16 36 COLENTINA 131105 203 205 261203 304 231 261 304 330 135 343 n tuz BUCURESTII NOI a R441 R442 R443 c 21 i CARTIER 605 tr 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 DEPOUL Bd. -

The Romanization of Romania: a Look at the Influence of the Roman Military on Romanian History and Heritage Colleen Ann Lovely Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2016 The Romanization of Romania: A Look at the Influence of the Roman Military on Romanian History and Heritage Colleen Ann Lovely Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Lovely, Colleen Ann, "The Romanization of Romania: A Look at the Influence of the Roman Military on Romanian History and Heritage" (2016). Honors Theses. 178. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/178 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Romanization of Romania: A Look at the Influence of the Roman Military on Romanian History and Heritage By Colleen Ann Lovely ********* Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Departments of Classics and Anthropology UNION COLLEGE March 2016 Abstract LOVELY, COLLEEN ANN The Romanization of Romania: A Look at the Influence of the Roman Military on Romanian History and Heritage. Departments of Classics and Anthropology, March 2016. ADVISORS: Professor Stacie Raucci, Professor Robert Samet This thesis looks at the Roman military and how it was the driving force which spread Roman culture. The Roman military stabilized regions, providing protection and security for regions to develop culturally and economically. Roman soldiers brought with them their native cultures, languages, and religions, which spread through their interactions and connections with local peoples and the communities in which they were stationed. -

Basic Police Training and Police Performance in the Netherlands

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file, please contact us at NCJRS.gov. wetenschappelijk onderzoek.. en documentatie centrum basic police training and police performance in the netherlands \;. I, .• , ministerie van justitie ~ <.:;.. .,' ....,... BASIC POLICE TRAINING AND POLICE PERFORMANCE IN THE NETHERLANDS Some Preliminary Findings of an Fvalnation Study on Police Training Written by: J. Junger-Tas If Research team: I' J. Junger-Tas A.A. v.d. Zee-Nefkens Research and Documentation Centre of the Ministry of Justice January 1977 CONTENTS I. BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY 1. Introduction 2. The training curriculum 3 3. The research-design 8 II. RESULTS OF THE OBSERVATION STUDY 9 1. How is working time organized? 9 2. Incidents observed 11 3. Police and citizens 14 CONCLUSIONS AND DISCUSSION 17 Literature Annex BASIC POLICE TRAINING AND POLICE PERFORMANCE IN THE NETHERLANDS Some Preliminary Findings of an Evaluation Study on Police Training I. BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY I. Introduction The role of the police in a democratic society ~s defined by many sources. Role definitions and the setting of priorities of tasks differ among such groups as police administrators, judicial authorities, police circles, and the general public. The Dutch Police Act of 1957 (Article 28) states: "It is the duty of the police, in subordination to the competent authorities and in accordance with the prevailing rules of the law, to maintain law and order and to render assistance to those in need". It appears then that the Dutch law recognizes essentially 3 functions: 1. to combat and prevent criminality 2. to maintain public order 3. -

C O N V E N T I O N Between the Hellenic Republic and Romania For

CONVENTION between the Hellenic Republic and Romania for the avoidance of double taxation with respect to taxes on income and on capital. The Government of the Hellenic Republic and the Government of Romania Desiring to promote and strengthen the economic relations between the two countries on the basis of national sovereignty and respect of independence, equality in rights, reciprocal advantage and non-interference in domestic matters; have agreed as follows: Article 1 PERSONAL SCOPE This Convention shall apply to persons who are residents of one or both of the Contracting States. Article 2 TAXES COVERED 1. This Convention shall apply to taxes on income and on capital imposed on behalf of a Contracting State or of its administrative territorial units or local authorities, irrespective of the manner in which they are levied. 2. There shall be regarded as taxes on income and on capital all taxes imposed on total income, on total capital, or on elements of income or of capital, including taxes on gains from the alienation of movable or immovable property, as well as taxes on capital appreciation. 3. The existing taxes to which the Convention shall apply are in particular: a) In the case of the Hellenic Republic: i) the income and capital tax on natural persons ; ii) the income and capital tax on legal persons; iii) the contribution for the Water Supply and Drainage Agencies calculated on the gross- income from buildings; (hereinafter referred to as "(Hellenic tax"). b) In the case of Romania: i) the individual income tax; ii) the tax on salaries, wages and other similar remunerations ; iii) the tax on the profits; iv) the tax on income realised by individuals from agricultural activities; hereinafter referred to as "Romania tax"). -

“Geothermal Energy in Ilfov County - Romania”

Ilfov County Council “Geothermal energy in Ilfov County - Romania” Ionut TANASE Ilfov County Council October, 2019 Content Ilfov County Council 1. Geothermal resources in Romania 2. Geothermal resources in Bucharest-Ilfov Region 3. Project “Harnessing geothermal water resources for district heating the Emergency Hospital «Prof. Dr. Agrippa Ionescu», Balotesti Commune, Ilfov County” 4. Project “The development of geothermal potential in the counties of Ilfov and Bihor” 5. Project ELI-NP (GSHP) 6. Possible future project in Ilfov County Romania Geothermal resources in Romania Ilfov County Council • The research for geothermal resources for energy purposes began in the early 60’s based on a detailed geological programme for hydrocarbon resources. • The geothermal potential - low-temperature geothermal systems • porous permeable formations such as the Pannonian sandstone, and siltstones specific (Western Plain, Olt Valley) or in fractured carbonate formations (Oradea, Bors and North Bucharest (Otopeni) areas). • First well for geothermal utilisation in Romania (Felix SPA Bihor) was drilled in 1885 to a depth of 51 m, yielding hot water of 49°C, maximum flow rate 195 l/s. • Since then over 250 wells have been drilled with a depth range of 800- 3,500 m, through which were discovered low-enthalpy geothermal resources with a temperature between 40 and 120°C. • The total installed capacity of the existing wells in Romania is about 480 MWth (for a reference temperature of 25°C). UCRAINE Ilfov County Council MOLDAVIA HUNGARY SATU-MARE CHIŞINĂU Acas -

Title of Paper

Noise pollution generated by road traffic in Bucharest Maria Pătroescu University of Bucharest, Centre for Environmental Research, Bucharest, Romania Cristian Iojă, Viorel Popescu, Radu Necşuliu University of Bucharest, Centre for Environmental Research, Bucharest, Romania ABSTRACT: Through the observations recorded by the Environmental Research Centre, University of Bu- charest, there can be noticed a significant level of noise pollution in Bucharest, caused mainly by the increase of the generating sources and the lack of antiphonic protection measures. The measurements realized in dif- ferent spots (intense traffic streets, industrial platforms, residential areas, market places) indicated that the highest values of the continuous equivalent acoustic level (Leq) appear on the 1st and 2nd category roads, where the heavy traffic is intense. The recorded Leq values were between 65 - 75 dB (A) for the 1st and 2nd category roads, frequently overpassing the maximum admitted level (70 dB(A)). In order to reduce the noise pollution it is necessary to diminish the noise level at the sources and to apply antiphonic protection measures (rehabilitation of forest protection belts, of the roads and tram lines, deviation of heavy traffic etc.). RÉSUMÉ : Par les observations enregistrées par le Centre de Recherche Environnemental de l'Université de Bucarest, on note un niveau significatif de nuisances sonores à Bucarest, causées principalement par l'aug- mentation des sources de production et le manque de mesures de protection antiphoniques. Les mesures effec- tuées dans divers lieux (des rues à forte circulation, des plates-formes industrielles, des secteurs résidentiels, des places de marché) ont indiqué que les valeurs les plus hautes du niveau équivalent acoustique (Leq) conti- nu apparaissent sur les routes de 1ère et 2ème catégorie, où le trafic lourd est intense.