6. Public Transport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anexe La H.C.G.M.B. Nr. 254 / 2008

NR. FELUL LIMITE DENUMIREA SECTOR CRT. ARTEREI DELA ..... PANA LA ..... 0 1 2 3 4 5 1 Bd. Aerogarii Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti Bd. Ficusului 1 2 Str. Avionului Sos. Pipera Linie CF Constanta 1 3 Bd. Averescu Alex. Maresal Bd. Ion Mihalache Sos. Kiseleff 1 4 Bd. Aviatorilor Pta Victoriei Sos. Nordului 1 5 P-ta Aviatorilor 1 6 Str. Baiculesti Sos. Straulesti Str. Hrisovului 1 7 Bd. Balcescu Nicolae Bd. Regina Elisabeta Str. CA Rosetti 1 8 Str. Baldovin Parcalabul Str. Mircea Vulcanescu Str. Cameliei .(J' 9 Bd. Banu Manta Sos. Nicolae Titulescu Bd. Ion Mihalache /'co 1 ~,..~:~':~~~.~. (;~ 10 Str. Beller Radu It. avo Calea Dorobanti Bd. Mircea Eliade ,i: 1 :"~," ~, ',.." " .., Str. Berzei ,;, 1 t~:~~:;:lf~\~l'~- . ~: 11 Str. Berthelot Henri Mathias, G-ral Calea Victoriei .. ~!- .~:,.-::~ ",", .\ 1.~ 12 P-ta Botescu Haralambie ~ . 13 Str. Berzei Calea Plevnei Calea Grivitei 1 ~; 14 Str. Biharia Bd. Aerogarii Str. Zapada Mieilor 1 15 Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti P-ta Presei Libere Str. Elena Vacarescu 1 16 Sos. Bucuresti Targoviste Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos.Odaii 1 17 Bd. Bucurestii Noi Calea Grivitei Sos. Bucurestii Targoviste 1 18 Str. Budisteanu Ion Str. G-ral Berthelot Calea Grivitei 1 19 Str. Buzesti Calea Grivitei P-ta Victoriei 1 20 P-ta Buzesti 1 21 Str. Campineanu Ion Str. Stirbei Voda Bd. Nicolae Balcescu 1 22 Str. Caraiman Calea Grivitei Bd. Ion Mihalache 1 23 Str. Caramfil Nicolae Sos. Nordului Str. Av. AI. Serbanescu 1 24 Bd. Campul Pipera Aleea Privighetorilor 1 25 P-ta Charles de Gaulle -'- 1 26 Sos. Chitilei ,.".ll·!A Bd. Bucurestii Noi Limita administrativa - 1 27 Str. -

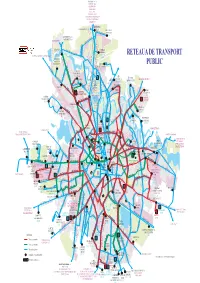

RETEA GENERALA 01.07.2021.Cdr

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 97 204 205 304 261 Sisesti BANEASA RETEAUA DE TRANSPORT R402 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 COMPLEX 112 205 261 97 131 261301 COMERCIAL Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti PUBLIC COLOSSEUM CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 203 335 361 605 780 783 112 R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 Bd. Aerogarii R402 97 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 24 331R436 CFR Str. Alex. Serbanescu 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 DRIDU Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 65 86 112 135 243 Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Bd. Gloriei24 Str. Jiului 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Sos. Chitilei Poligrafiei PIATA PLATFORMA Bd. BucurestiiPajurei Noi 231 243 Str. Peris MEZES 780 783 INDUSTRIALA Str. PRESEI Str.Oi 3 45 65 86 331 243 3 45 382 PASAJ Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 3 41 243 PIPERA 382 DEPOUL R447 R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 i 65 86 97 243 16 36 COLENTINA 131105 203 205 261203 304 231 261 304 330 135 343 n tuz BUCURESTII NOI a R441 R442 R443 c 21 i CARTIER 605 tr 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 DEPOUL Bd. -

Planul Regional De Actiune Pentru Mediu Bucuresti-Ilfov

MINISTERUL MEDIULUI ŞI DEZVOLTĂRII DURABILE AGENŢIA NAŢIONALĂ PENTRU PROTECŢIA MEDIULUI AGENŢIA REGIONALĂ PENTRU PROTECŢIA MEDIULUI BUCUREŞTI PLANUL REGIONAL DE ACŢIUNE PENTRU MEDIU BUCUREŞTI - ILFOV Bucureşti, Martie 2008 CUPRINS 1. INTRODUCERE........................................................................................................................................ 9 POLUAREA ATMOSFEREI GENERATĂ DE TRAFICUL RUTIER: PARCUL AUTO CU UZURĂ MORALĂ ŞI FIZICĂ ÎNAINTATĂ, ÎNTREŢINEREA DEFECTUOASĂ A ARTERELOR RUTIERE...................................................................................................................................................... 47 DISCONFORTUL OLFACTIV PRODUS DE DEPOZITAREA TEMPORARĂ SAU DEFINITIVĂ A DEŞEURILOR..........................................................................................................................................47 Planul Regional de Acţiune pentru Mediu Bucureşti - Ilfov POLUAREA ATMOSFEREI GENERATĂ DE TRAFICUL RUTIER: PARCUL AUTO CU UZURA MORALĂ ŞI FIZICĂ ÎNAINTATĂ, ÎNTREŢINEREA DEFECTUOASĂ A ARTERELOR RUTIERE...................................................................................................................................................... 54 DISCONFORTUL OLFACTIV PRODUS DE DEPOZITAREA TEMPORARĂ SAU DEFINITIVĂ A DEŞEURILOR..........................................................................................................................................54 POLUAREA ATMOSFEREI GENERATĂ DE TRAFICUL RUTIER: PARCUL AUTO CU UZURĂ MORALĂ ŞI FIZICĂ -

Perioada 22-30.07.2019

INFORMARE În perioada 22 – 30.07.2019, se vor efectua tratamente fitosanitare în vederea combaterii bolilor şi dăunătorilor plantelor (combaterea afidelor, omidei păroase a dudului generațiile I și II, tigrului platanului, ploșnițelor, acarienilor, tripșilor, omidei buxusului, moliei castanului, cicadei albe, precum și combaterea ruginei, făinării, manei, verciliozei, pătarea brună a frunzelor, arsura bacteriană, cancerul trandafirilor, antracnozei, moniliozei, etc.) pe teritoriul Municipiului Bucureşti. Produsele fitosanitare folosite, omologate U.E și de către Autoritatea Națională Fitosanitară sunt: Vertimec 1.8 EC, Score 250 EC, Bravo 500 SC, Ortus 5 SC și Teppeki. NR. DENUMIREA ZONEI DE ACȚIUNE DATA ȘI INTERVALUL CRT. PARCURI/ALINIAMENTE TRATAMENTULUI ALINIAMENTE SECTOR 1 – zonele cuprinse între: • Str. Drumul Poiana Horea – Str. Naturaliștilor – Str. Chitila Triaj – Str. Lămâiului – Str. Cpt. Av. Hubert Dumitru – Str. Prunaru – Calea Giulești - Drumul Săbăreni; • Calea Giulești – Str. Jugastrului – Str. Mânzului –Str. Lămâiului – Str. Butuceni – Calea Giulești – Str. Prunaru; • Bd. Bucureștii Noi - Șos. Chitila – Bd. Laminorului; • Bd. Laminorului – Bd. Bucureștii Noi –Str. Slt. Godeanu C-tin – Str. Ștefan Magheri – Str. Petru și Pavel - Șos. Chitila; • Șos. Chitila– Str. Crușovăț - Str. Mimozei – Str. Vălenii de Munte – Str. Cpt. Dragoș Radu; • Str. Crușovăț - Str. Mimozei – Str. Marginei – Str. Inovatorului - Șos. Chitilei; • Bd. Gloriei – Str. Piatra Morii – Str. Coralilor - Șos. Străulești - Șos. Gh. Ionescu Sisești – Bd. Apicultorilor – Str. Pădurii – Str. Jandarmeriei –Str. Drumul Regimentului – Str. Drumul Piscul Radului -Șos. Gh. Ionescu Sisești – Bd. Bucureștii Noi – Str. Laminorului – Str. Fabrica de Cărămidă – Str. Cireșoaia; • Str. Cireșoaia – Str. Fabrica de Cărămidă – Str. Laminorului – Bd. Bucureștii Noi; 22.07.2019 1. • Calea Griviței - Str. Caransebeș - Str. Milcov - Str. Mureș - Str. Ceremușului - Str. -

Intermodality in Urban Passenger Transport

Conference Proceedings of the Academy of Romanian Scientists PRODUCTICA Scientific Session ISSN 2067-9564 Volume 11, Number 1/2019 9 INTERMODALITY IN URBAN PASSENGER TRANSPORT Flavius GRIGORE1, Petruț CLADOVEANU2 Rezumat. Intermodalitatea este o parte integrantă a mobilității durabile, iar îmbunătățirea acesteia este deosebit de importantă în zonele urbane aglomerate. Orașele sunt în creștere în prezent, la fel și cererea cetățenilor pentru mobilitate. Pe scară globală, traficul individual este motorizat,abia capabil să răspundă acestei nevoi din cauza costurilor de proprietate și datorită lipsei unei infrastructuri corespunzătoare. În afara de asta, traficul cu automobilul personal este responsabil pentru majoritatea sarcinilor de circulație actuale, cum ar fi poluarea aerului, blocajele de trafic, zgomotul și accidentele. O astfel de utilizare a diferitelor moduri de transport într-o singură călătorie se numește "intermodalitate" și este un subiect de lucru încurajat într-un context național, european și mondial. Abstract. Intermodality is an integral part of the sustainable mobility and its enhancement is of vital importance particularly, in high congested urban areas. Cities are growing nowadays and so is their citizens’ demand for mobility. On a global scale, motorized individual traffic is hardly capable of meeting this need due to its ownership costs and due to the lack of an accordingly large infrastructure. Besides, motorized individual traffic is responsible for the majority of today's traffic burdens, such as air pollution, traffic jams, noise, and accidents. Such a use of different transport modes within a single journey is called “intermodality” and is a work topic fostered in a national, European, and world- wide context. Keywords : intermodality, urban transport, passenger intermodal transport, public transport 1. -

Trip #1 Welcome in Bucharest “The City of Joy” 5-6 Hours

Trip #1 Welcome in Bucharest “The City of Joy” 5-6 hours Meet the English speaking guide in the airport. Half day to discover Bucharest, the capital city of Romania. You’ll visit: Free Press Square, The Arch of Triumph, Victoriei Square, Revolution Square, Romanian Atheneum – The Palace of Parliament – Union Square – University Square – Romana Square – Victoriei Square – Charles de Gaulle Square – Village Museum Once known as the “Little Paris”, Bucharest is a green city with large tree-linen boulevards dominated by many architectural styles, from classical, baroque and French renaissance to Art Deco and modern style. Legend says that the founder of the settlement was a shepherd named Bucur. Visit Parliament House, the second large building of the world after Pentagon. Built by the Communist Party leader, Nicolae Ceausescu, the colossal Parliament Palace (formerly known as the People's Palace) is the second largest administrative building in the world after the Pentagon. It took 20,000 workers and 700 architects to build. The palace boasts 12 stores, 1,100 rooms, a 328-ft-long lobby and four underground levels, including an enormous nuclear bunker. Lunch in a traditional restaurant. Transfer to Sinaia. Price in euro / person: No of persons 1 pax 2 pax 3 pax 4-7 pax 8-12 pax 13-18 pax 19-24 pax 225 € 130 € 105 € 93 € 69 € 58 € 52 € The above price includes: - 1 lunch (3 courses + mineral water) - English speaking guide from arrival till departure - Air-conditioned car (for 1-3 pax), van, minibus or coach for all the above itinerary and program; - Entrance fees to all the above mentioned museums and sites - All Romanian taxes. -

Trasee De Noapte

PROGRAMUL DE TRANSPORT PENTRU RETEAUA DE AUTOBUZE - TRASEE DE NOAPTE Plecari de la capete de Linia Nr Numar vehicule Nr statii TRASEU CAPETE lo traseu Lungime c 23 00:30 1 2 03:30 4 5 Prima Ultima Dus: Şos. Colentina, Şos. Mihai Bravu, Bd. Ferdinand, Şos. Pantelimon, Str. Gǎrii Cǎţelu, Str. N 101 Industriilor, Bd. Basarabia, Bd. 1 Dus: Decembrie1918 0 2 2 0 2 0 0 16 statii Intors: Bd. 1 Decembrie1918, Bd. 18.800 m Basarabia, Str. Industriilor, Str. Gǎrii 88 Intors: Cǎţelu, Şos. Pantelimon, Bd. 16 statii Ferdinand, Şos. Mihai Bravu, Şos. 18.400 m Colentina. Terminal 1: Pasaj Colentina 00:44 03:00 Terminal 2: Faur 00:16 03:01 Dus: Piata Unirii , Bd. I. C. Bratianu, Piata Universitatii, Bd. Carol I, Bd. Pache Protopopescu, Sos. Mihai Bravu, Str. Vatra Luminoasa, Bd. N102 Pierre de Coubertin, Sos. Iancului, Dus: Sos. Pantelimon 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 19 statii Intors: Sos. Pantelimon, Sos. Iancului, 8.400 m Bd. Pierre de Coubertin, Str. Vatra 88 Intors: Luminoasa, Sos. Mihai Bravu, Bd. 16 statii Pache Protopopescu, Bd. Carol I, 8.600 m Piata Universitatii, Bd. I. C. Bratianu, Piata Unirii. Terminal 1: Piata Unirii 2 23:30 04:40 Terminal 2: Granitul 22.55 04:40 Dus: Bd. Th. Pallady, Bd. Camil Ressu, Cal. Dudeşti, Bd. O. Goga, Str. Nerva Traian, Cal. Văcăreşti, Şos. Olteniţei, Str. Ion Iriceanu, Str. Turnu Măgurele, Str. Luică, Şos. Giurgiului, N103 Piaţa Eroii Revoluţiei, Bd. Pieptănari, us: Prelungirea Ferentari 0 2 1 0 2 0 0 24 statii Intors: Prelungirea Ferentari, , Bd. -

Office for Rent in Beller Office Building Bucharest, Str. Radu Beller 22

Homepage / B category / Beller Office Building Beller Office Building Bucharest, Str. Radu Beller 22 Office Rental Fee (m2 / month) Available Office Space : 14 €/m2 Rented Service Charge: - Min. Office Space for Rent: - Bucharest, Str. Radu Beller 22 Office Rental Fee (m2 / month) Available Office Space: 14 €/m2 Rented Spatial Data Office Building Category: B category Description Location: Dorobanti, Aviatorilor <p><span lang="EN-GB"><strong>Beller Office Building</strong> is a modern designed office building finished to high standards located in Building Status: Exist Sector 1, near Dorobantilor Square in the north of Romania’s capital, 2 Bucharest.</span></p> Office Space in Total : 499 m <p><span lang="EN-GB">The building has prominent street frontage on Available Office Space : Rented Radu Beller Street and is less than 10 minutes walk from Aviatorilor metro station.</span></p> Rentable Offices : - <p><span lang="EN-GB">Dorobantilor Square is known for its cafes, pubs, fruit & vegetable market and delicatessens. Dorobantilor is strategically located between the established business districts of Min. Office Space for Rent : - lower Pipera, Charles de Gaulle Square, Victoriei Square and in the vicinity of most embassies.</span></p> Add-on Factor: 10 % <p><span lang="EN-GB">Due to its location, the area is well served by a wide range of civic amenities:</span></p> Occupancy Rate: 100% <p><span lang="EN-GB"><strong>Health-care:</strong></span></p> <p><span lang="EN-GB">• public: Floreasca Emergency Hospital, Parhon, Elias, Grigore Alexandrescu;</span></p> <p><span lang="EN-GB">• private: Euroclinic, Biomedica.</span></p> Financial Information <p><span lang="EN-GB"><strong>Hotels:</strong> Howard Jhonson (5 Office Rental Fee: 14 €/m2/month stars) – 3-5 Dorobantilor Way, Green Forum (3 stars) – 19 Pictor Barbu Iscovescu, Hotel Helvetia (3 stars) – 13 Charles de Gaulle Square Service Charge: - etc</span></p> <p><span lang="EN-GB"><strong>Restaurants:</strong> White Horse, La Min. -

Astaldi06 INGL

annual report2006 “To consolidate as leading Italian General Contractor and mission enhance value, progress and well-being for the communities” main ratios ratios (million of euro) 2006 2005 2004 (percentage) R.O.S. R.O.I. R.O.E. economic items total revenues 1,072 1,021 1,054 40.0% 30.5 30.5 EBIT 78 78 71 30.0% 27.8 profit before interests 61 55 43 20.0% 15.8 15.4 net income 30 32 28 13.8 10.0% 7.3 7.6 6.7 financial items 0.0% gross self-financing margin 60 69 52 capital expenditure 109 47 50 % on total revenues 2006 2005 2004 EBIT 7.3% 7.6% 6.7% R.O.S. = EBIT / total revenues R.O.I. = EBIT / net invested capital profit before interests 5.7% 5.3% 4.1% R.O.E. = EBIT / net equity net income 2.8% 3.2% 2.7% balance sheet items (values) GEARING RATIO CURRENT RATIO QUICK RATIO total fixed assets 331 213 178 net invested capital 567 493 461 2.5 net debt (*) 281 231 115 2.0 net equity 281 256 233 1.5 1.3 1.3 1.3 1.1 1.0 1.0 0.9 1.0 1.0 0,5 0.5 (*) Net of own shares. 0.0 order backlog by lines of business 2006 2005 2004 (million of euro) GEARING RATIO = net financial indebtedness / net equity CURRENT RATIO = short-term assets / short-term liabilities 2006 2005 QUICK RATIO = total account receivables and cash / short-term liabilities 24% 47% 27% 39% ■ ■ (million of euro) EBITDA EBIT EBT 200 ■ ■ 150 126 7% 116 113 100 78 78 71 9% 61 5% 50 55 43 5% 0 1% 15% 1% 21% 2006 2005 railways and subways 3,279 2,167 2006 2005 2004 EBITDA = income before interests, taxes, depreciation and amortization roads and motorways 1,036 1,156 EBIT = income before interests -

Bucharest Barks: Street Dogs, Urban Lifestyle Aspirations, and the Non-Civilized City

Bucharest Barks: Street Dogs, Urban Lifestyle Aspirations, and the Non-Civilized City by Lavrentia Karamaniola A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2017 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Krisztina E. Fehérváry, Co-Chair Professor Alaina M. Lemon, Co-Chair Professor Liviu Chelcea, University of Bucharest Associate Professor Matthew S. Hull Professor Robin M. Queen “The gods had condemned Sisyphus to ceaselessly rolling a rock to the top of a mountain, whence the stone would fall back of its own weight. They had thought with some reason that there is no more dreadful punishment than futile and hopeless labor.” “I leave Sisyphus at the foot of the mountain! One always finds one's burden again. But Sisyphus teaches the higher fidelity that negates the gods and raises rocks. He too concludes that all is well. This universe henceforth without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile. Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man's heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” Extracts from “Sisyphus Myth” (1942) by Albert Camus (1913–1960) Sisyphus by Titian (1490–1567) 1548–1549. Oil on canvas, 237 x 216 cm Prado Museum, Madrid Lavrentia Karamaniola [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2194-3847 © Lavrentia Karamaniola 2017 Dedication To my family, Charalambos, Athena, Yannis, and Dimitris for always being close, for always nourishing their birbilo, barbatsalos, kounioko and zoumboko To Stefanos, for always smoothing the road for me to push the rock uphill ii Acknowledgments This project could not have been possible without the generous and continuous support of a number of individuals and institutions. -

BULETINUL AFER - Anul VI Nr

Ordinul ministrului transporturilor, construcĠilor úi turismului nr. 1044/18.12.2003 privind aprobarea Regulamentului pentru desemnarea, pregătirea profesională úi examinarea consilierilor de siguranĠă pentru transportul rutier, feroviar sau pe căile navigabile interioare al mărfurilor periculoase ……………………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Metodologia de acordare a certificatului privind pregătirea profesională a consilierului de siguranĠă pentru transportul mărfurilor periculoase în trafic feroviar ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 8 Hotărârea guvernului nr. 027/15.01.2004 pentru aprobarea condiĠiilor de închiriere de către Compania NaĠională de Căi Ferate "C.F.R." - S.A. a unor păUĠi din infrastructura feroviară neinteroperabilă, precum úi de gestionare a acestora …………………………… 13 Ordinul ministrului transporturilor, construcĠilor úi turismului nr. 538/22.03.2004 pentru aprobarea Normelor specifice privind componenĠa úi modul de lucru ale comisiei de evaluare, termenele de realizare a licitaĠiilor, precum úi procedura de soluĠionare a contestaĠiilor pentru licitaĠiile având ca obiect închirierea secĠiilor de circulaĠie aparĠinând infrastructurii feroviare neinteroperabile ….. 20 Ordinul ministrului transporturilor, construcĠilor úi turismului nr. 416/08.03.2004 pentru aprobarea InstrucĠiunilor pentru preîntâmpinare úi combaterea înzăpezirilor la calea ferată - nr. 311 ………………………………………………………………………….. 21 Ordinul ministrului transporturilor, construcĠilor úi turismului nr. 417/08.03.2004 pentru aprobarea InstrucĠiunilor pentru -

Driving Restrictions, Goods Transport Germany 2019 Vehicles Concerned Trucks with a Total Permissible Weight of Over 7.5T, As We

Driving Restrictions, Goods Transport Germany 2019 Vehicles concerned trucks with a total permissible weight of over 7.5t, as well as trucks with trailers in case of business-like/commercial or paid transportation of goods including related empty runs. Area throughout the road and motorway network Prohibition Sundays and public holidays from 00h00 to 22h00 Exceptions (applies also to the additional summer driving restrictions) 1. Combined rail/road goods transport from the shipper to the nearest loading railway station or from the nearest designated unloading railway station to the consignee up to a distance of 200km (no limitation on distance during the additional summer restrictions); also combined sea/road goods transport between the place of loading or unloading and a port situated within a radius of 150km maximum (delivery or loading). 2. Deliveries of fresh milk and other dairy produce, fresh meat and its fresh derivatives, fresh fish, live fish and their fresh derivatives, perishable foodstuffs (fruit and vegetables). 3. Transportation of animal by-products according to category 1, Art. 8 as well as category 2, Art. 9f of regulation (EG) No. 1069/2009. 4. Use of vehicles of recovery, towing and breakdown services in case of an accident or other emergencies. 5. Transport of living bees. 6. Empty vehicles, in connection with the transport operations mentioned under point 2-5. 7. Transport operations using vehicles subject to the Federal Law on the obligations of service; the relevant authorisation must be carried on board and produced for inspection on request. Also exempted from the prohibition are vehicles belonging to the police and federal border guard, fire brigades and emergency services, the federal armed services and allied troops.