Residential Areas with Deficient Access to Urban Parks in Bucharest – Priority Areas for Urban Rehabilitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anexe La H.C.G.M.B. Nr. 254 / 2008

NR. FELUL LIMITE DENUMIREA SECTOR CRT. ARTEREI DELA ..... PANA LA ..... 0 1 2 3 4 5 1 Bd. Aerogarii Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti Bd. Ficusului 1 2 Str. Avionului Sos. Pipera Linie CF Constanta 1 3 Bd. Averescu Alex. Maresal Bd. Ion Mihalache Sos. Kiseleff 1 4 Bd. Aviatorilor Pta Victoriei Sos. Nordului 1 5 P-ta Aviatorilor 1 6 Str. Baiculesti Sos. Straulesti Str. Hrisovului 1 7 Bd. Balcescu Nicolae Bd. Regina Elisabeta Str. CA Rosetti 1 8 Str. Baldovin Parcalabul Str. Mircea Vulcanescu Str. Cameliei .(J' 9 Bd. Banu Manta Sos. Nicolae Titulescu Bd. Ion Mihalache /'co 1 ~,..~:~':~~~.~. (;~ 10 Str. Beller Radu It. avo Calea Dorobanti Bd. Mircea Eliade ,i: 1 :"~," ~, ',.." " .., Str. Berzei ,;, 1 t~:~~:;:lf~\~l'~- . ~: 11 Str. Berthelot Henri Mathias, G-ral Calea Victoriei .. ~!- .~:,.-::~ ",", .\ 1.~ 12 P-ta Botescu Haralambie ~ . 13 Str. Berzei Calea Plevnei Calea Grivitei 1 ~; 14 Str. Biharia Bd. Aerogarii Str. Zapada Mieilor 1 15 Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti P-ta Presei Libere Str. Elena Vacarescu 1 16 Sos. Bucuresti Targoviste Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos.Odaii 1 17 Bd. Bucurestii Noi Calea Grivitei Sos. Bucurestii Targoviste 1 18 Str. Budisteanu Ion Str. G-ral Berthelot Calea Grivitei 1 19 Str. Buzesti Calea Grivitei P-ta Victoriei 1 20 P-ta Buzesti 1 21 Str. Campineanu Ion Str. Stirbei Voda Bd. Nicolae Balcescu 1 22 Str. Caraiman Calea Grivitei Bd. Ion Mihalache 1 23 Str. Caramfil Nicolae Sos. Nordului Str. Av. AI. Serbanescu 1 24 Bd. Campul Pipera Aleea Privighetorilor 1 25 P-ta Charles de Gaulle -'- 1 26 Sos. Chitilei ,.".ll·!A Bd. Bucurestii Noi Limita administrativa - 1 27 Str. -

Historical GIS: Mapping the Bucharest Geographies of the Pre-Socialist Industry Gabriel Simion*, Alina Mareci, Florin Zaharia, Radu Dumitru

# Gabriel Simion et al. Human Geographies – Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography Vol. 10, No. 2, November 2016 | www.humangeographies.org.ro ISSN–print: 1843–6587 | ISSN–online: 2067–2284 Historical GIS: mapping the Bucharest geographies of the pre-socialist industry Gabriel Simion*, Alina Mareci, Florin Zaharia, Radu Dumitru University of Bucharest, Romania This article aims to map the manner in which the rst industrial units crystalized in Bucharest and their subsequent dynamic. Another phenomenon considered was the way industrial sites grew and propagated and how the rst industrial clusters formed, thus amplifying the functional variety of the city. The analysis was undertaken using Historical GIS, which allowed to integrate elements of industrial history with the location of the most important industrial objectives. Working in GIS meant creating a database with the existing factories in Bucharest, but also those that had existed in different periods. Integrating the historical with the spatial information about industry in Bucharest was preceded by thorough preparations, which included geo-referencing sources (city plans and old maps) and rectifying them. This research intends to serve as an example of how integrating past and present spatial data allows for the analysis of an already concluded phenomenon and also explains why certain present elements got to their current state.. Key Words: historical GIS, GIS dataset, Bucharest. Article Info: Received: September 5, 2016; Revised: October 24, 2016; Accepted: November 15, 2016; Online: November 30, 2016. Introduction The spatial evolution of cities starting with the ending of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th is closely connected to their industrial development. -

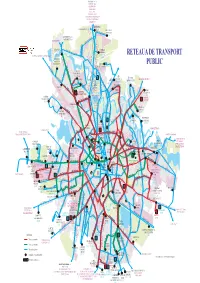

RETEA GENERALA 01.07.2021.Cdr

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 97 204 205 304 261 Sisesti BANEASA RETEAUA DE TRANSPORT R402 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 COMPLEX 112 205 261 97 131 261301 COMERCIAL Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti PUBLIC COLOSSEUM CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 203 335 361 605 780 783 112 R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 Bd. Aerogarii R402 97 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 24 331R436 CFR Str. Alex. Serbanescu 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 DRIDU Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 65 86 112 135 243 Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Bd. Gloriei24 Str. Jiului 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Sos. Chitilei Poligrafiei PIATA PLATFORMA Bd. BucurestiiPajurei Noi 231 243 Str. Peris MEZES 780 783 INDUSTRIALA Str. PRESEI Str.Oi 3 45 65 86 331 243 3 45 382 PASAJ Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 3 41 243 PIPERA 382 DEPOUL R447 R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 i 65 86 97 243 16 36 COLENTINA 131105 203 205 261203 304 231 261 304 330 135 343 n tuz BUCURESTII NOI a R441 R442 R443 c 21 i CARTIER 605 tr 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 DEPOUL Bd. -

People's Advocate

European Network of Ombudsmen THE 2014 REPORT OF PEOPLE’S ADVOCATE INSTITUTION - SUMMARY - In accordance with the provisions of art. 60 of the Constitution and those of art. 5 of Law no. 35/1997 on the organization and functioning of the People's Advocate Institution, republished, with subsequent amendments, the Annual Report concerning the activity of the institution for one calendar year is submitted by the People's Advocate, until the 1st of February of the following year, to Parliament for its debate in the joint sitting of the two Chambers. We present below a summary of the 2014 Report of the People’s Advocate Institution, which has been submitted to Parliament, within the legal deadline provided by Law no. 35/1997. GENERAL VOLUME OF ACTIVITY The overview of the activity in 2014 can be summarized in the following statistics: - 16,841 audiences , in which violations of individuals' rights have been alleged, out of which 2,033 at the headquarters and 14,808 at the territorial offices; - 10,346 complaints registered at the People's Advocate Institution, out of which 6,932 at the headquarters and 3,414 at the territorial offices; Of these, a total of 7,703 complaints were sent to the People's Advocate on paper, 2,551 by email, and 92 were received from abroad. - 8,194 calls recorded by the dispatcher service, out of which 2,504 at the headquarters and 5,690 at the territorial offices; - 137 investigations conducted by the People's Advocate Institution, out of which 33 at the headquarters and 104 at the regional offices; - 56 ex officio -

LIST of HOSPITALS, CLINICS and PHYSICIANS with PRIVATE PRACTICE in ROMANIA Updated 04/2017

LIST OF HOSPITALS, CLINICS AND PHYSICIANS WITH PRIVATE PRACTICE IN ROMANIA Updated 04/2017 DISCLAIMER: The U.S. Embassy Bucharest, Romania assumes no responsibility or liability for the professional ability or reputation of, or the quality of services provided by the medical professionals, medical facilities or air ambulance services whose names appear on the following lists. Names are listed alphabetically, and the order in which they appear has no other significance. Professional credentials and areas of expertise are provided directly by the medical professional, medical facility or air ambulance service. When calling from overseas, please dial the country code for Romania before the telephone number (+4). Please note that 112 is the emergency telephone number that can be dialed free of charge from any telephone or any mobile phone in order to reach emergency services (Ambulances, Fire & Rescue Service and the Police) in Romania as well as other countries of the European Union. We urge you to set up an ICE (In Case of Emergency) contact or note on your mobile phone or other portable electronics (such as Ipods), to enable first responders to get in touch with the person(s) you designated as your emergency contact(s). BUCHAREST Ambulance Services: 112 Private Ambulances SANADOR Ambulance: 021-9699 SOS Ambulance: 021-9761 BIOMEDICA Ambulance: 031-9101 State Hospitals: EMERGENCY HOSPITAL "FLOREASCA" (SPITALUL DE URGENTA "FLOREASCA") Calea Floreasca nr. 8, sector 1, Bucharest 014461 Tel: 021-599-2300 or 021-599-2308, Emergency line: 021-962 Fax: 021-599-2257 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.urgentafloreasca.ro Medical Director: Dr. -

Download This PDF File

THE SOCIO-SPATIAL DIMENSION OF THE BUCHAREST GHETTOS Viorel MIONEL Silviu NEGUŢ Viorel MIONEL Assistant Professor, Department of Economics History and Geography, Faculty of International Business and Economics, Academy of Economic Studies, Bucharest, Romania Tel.: 0040-213-191.900 Email: [email protected] Abstract Based on a socio-spatial analysis, this paper aims at drawing the authorities’ attention on a few Bucharest ghettos that occurred after the 1990s. Silviu NEGUŢ After the Revolution, Bucharest has undergone Professor, Department of Economics History and Geography, many socio-spatial changes. The modifications Faculty of International Business and Economics, Academy of that occurred in the urban perimeter manifested Economic Studies Bucharest, Romania in the technical and urban dynamics, in the urban Tel.: 0040-213-191.900 infrastructure, and in the socio-economic field. The Email: [email protected] dynamics and the urban evolution of Bucharest have affected the community life, especially the community homogeneity intensely desired during the communist regime by the occurrence of socially marginalized spaces or ghettos as their own inhabitants call them. Ghettos represent an urban stain of color, a special morphologic framework. The Bucharest “ghettos” appeared by a spatial concentration of Roma population and of poverty in zones with a precarious infrastructure. The inhabitants of these areas (Zăbrăuţi, Aleea Livezilor, Iacob Andrei, Amurgului and Valea Cascadelor) are somehow constrained to live in such spaces, mainly because of lack of income, education and because of their low professional qualification. These weak points or handicaps exclude the ghetto population from social participation and from getting access to urban zones with good habitations. -

Cartare Infrastructura Etapa1.Pdf

Nr.contract: 829/22.07.2015 CARTARE INFRASTRUCTURĂ LA NIVELUL MUNICIPIULUI BUCUREȘTI Spații potențiale pentru activități culturale/ creative Beneficiar: Centrul de Proiecte Culturale al Municipiului București- ArCub Proiectant: UNIVERSITATEA DE ARHITECTURA ”ION MINCU” – CENTRUL DE CERCETARE, PROIECTARE, EXPERTIZĂ ŞI CONSULTING BUCUREŞTI UNIVERSITATEA DE ARHITECTURĂ ”ION MINCU” – CENTRUL DE CERCETARE, PROIECTARE, EXPERTIZĂ ŞI CONSULTING BUCUREŞTI Manager General: Prof. dr. arh. Emil Barbu Popescu Director: ec. Dana Racu Coordonator proiect: lect.dr.urb. Andreea Popa Colectiv de elaborare: prof.dr.arh. Tiberiu Florescu conf. dr. arh. Cerasella Craciun conf. dr. arh. Cristina Enache lect. dr . urb. Andreea Popa dr. arh. Catalina Ionita asist. dr. urb. Mihai Alexandru asist. dr. urb. peisag. Sorina Rusu asist. dr. urb. peisag. Andreea Bunea dr. urb. peisag. Irina Pata ms. urb. Nicolae Ionut Negrea urb. Corina Chirila st. arh. Ram Gretcu st. urb. peisag. Marin Gabi st. urb. Brastaviceanu Marilena 2 CUPRINS 1. DEFINIREA OBIECTIVELOR STUDIULUI ................................................................. 4 1.1. Contextul și problematica studiului ................................................................................ 4 1.2. Scopul și obiectivele studiului ........................................................................................ 6 1.3 Delimitarea zonei de studiu din București ...................................................................... 8 2. DISPUNERE ZONE CU POTENȚIAL LA NIVELUL MUNICIPIULUI BUCUREȘTI - Criterii -

Trasee De Noapte

PROGRAMUL DE TRANSPORT PENTRU RETEAUA DE AUTOBUZE - TRASEE DE NOAPTE Plecari de la capete de Linia Nr Numar vehicule Nr statii TRASEU CAPETE lo traseu Lungime c 23 00:30 1 2 03:30 4 5 Prima Ultima Dus: Şos. Colentina, Şos. Mihai Bravu, Bd. Ferdinand, Şos. Pantelimon, Str. Gǎrii Cǎţelu, Str. N 101 Industriilor, Bd. Basarabia, Bd. 1 Dus: Decembrie1918 0 2 2 0 2 0 0 16 statii Intors: Bd. 1 Decembrie1918, Bd. 18.800 m Basarabia, Str. Industriilor, Str. Gǎrii 88 Intors: Cǎţelu, Şos. Pantelimon, Bd. 16 statii Ferdinand, Şos. Mihai Bravu, Şos. 18.400 m Colentina. Terminal 1: Pasaj Colentina 00:44 03:00 Terminal 2: Faur 00:16 03:01 Dus: Piata Unirii , Bd. I. C. Bratianu, Piata Universitatii, Bd. Carol I, Bd. Pache Protopopescu, Sos. Mihai Bravu, Str. Vatra Luminoasa, Bd. N102 Pierre de Coubertin, Sos. Iancului, Dus: Sos. Pantelimon 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 19 statii Intors: Sos. Pantelimon, Sos. Iancului, 8.400 m Bd. Pierre de Coubertin, Str. Vatra 88 Intors: Luminoasa, Sos. Mihai Bravu, Bd. 16 statii Pache Protopopescu, Bd. Carol I, 8.600 m Piata Universitatii, Bd. I. C. Bratianu, Piata Unirii. Terminal 1: Piata Unirii 2 23:30 04:40 Terminal 2: Granitul 22.55 04:40 Dus: Bd. Th. Pallady, Bd. Camil Ressu, Cal. Dudeşti, Bd. O. Goga, Str. Nerva Traian, Cal. Văcăreşti, Şos. Olteniţei, Str. Ion Iriceanu, Str. Turnu Măgurele, Str. Luică, Şos. Giurgiului, N103 Piaţa Eroii Revoluţiei, Bd. Pieptănari, us: Prelungirea Ferentari 0 2 1 0 2 0 0 24 statii Intors: Prelungirea Ferentari, , Bd. -

Bucharest Meet: Iuliu Maniu and Vasile Milea

#welcome @ CAMPUS 6 swipe page to begin Homepage #theagenda 1.0 Futureproof 2.0 Location & Amenities 3.0 Site Plan 4.0 Placemaking & Social Impact 5.0 Interior & Innovations 6.0 Green Features 7.0 About Us 8.0 Contact 1.0 Futureproof 1 Architecture 2 Placemaking 3 Art We stand by our promise to deliver high-class offices, combining the best design practices, the principles of sustainable development and technological innovation. We offer our customers solutions that support their present and future needs. 1 Products 1 Wellbeing 2 Connected by Skanska 2 Biodiversity 3 BIM 3 Certification 1.0 Futureproof We are constantly looking for new materials and technological solutions so that our buildings are ready for the challenges of the future. INNOVATIONS What does it mean to us? Trends come and go and style evolves. Futureproof is a symbol that defines the focus areas that make Skanska a trustworthy partner. Our investments are determined by functionality, low maintenance costs and minimal impact on the environment. Located in the best spots in the city, they are highly valuable assets on the office buildings market. Sustainable development is in our company’s DNA, therefore we design and construct our buildings aiming to benefit the society and respect the environment. SUSTAINABILITY Based on our Scandinavian roots and cooperation with top-notch architects, we provide timeless and functional design of our buildings. DESIGN 2.0 Location & Amenities #welcome We designed Campus 6 with one goal: to change Campus the way people mix life and work. 6.1 Q3 2018 Campus sqm 6.2 81 000 GLA in 4 phases Q4 2019 1 000 parking places floors of office spaces Campus 10 6.3 Q3 2021 Campus 6.4 Q4 2022 POLITEHNICA UNIVERSITY Campus 6.3 Campus 6.4 Campus 6.2 Campus 6.1 Iuliu Maniu Ave. -

Lista Afiliati in Cadrul Programului "O Sansa Pentru Cuplurile Infertile" Fiv 2

LISTA AFILIATI IN CADRUL PROGRAMULUI "O SANSA PENTRU CUPLURILE INFERTILE" FIV 2 Nr. FARMACII Adresă Sector Telefon E-mail crt. 1 Dona 197 Str. Almas, nr. 2-8, Piata 16 Februarie 1 0372 407 197 [email protected] 2 Dona 235 Bd. Bucurestii Noi 62, lot 2 1 0372 407 235 [email protected] 3 Dona 60 Bd. Ion Mihalache nr. 168D 1 0372 407 060 [email protected] 4 Dona 33 Bd. Ion Mihalache, nr. 197 1 0372 407 033 [email protected] 5 Dona 17 Calea Dorobanti, nr. 102-110 1 0372 407 017 [email protected] 6 Dona 54 Str Hatmanul Arbore 15-19 1 0372 032 534 [email protected] 7 Dona 287 Bd. Magheru nr. 32-36 1 0372 401 287 [email protected] 8 Dona 396 Complex Comercial Piata Pajura, nr. 7 1 0372 401 828 [email protected] 9 Farmacaia Elexa Piata Charles de Gaulle 2, ap 2, Corp B 1 0728808570 [email protected] 10 Farmacia Medlife PharmaLife Calea Grivitei nr. 365 1 0735.300.990 [email protected] 11 Farmacia Pharma-Plant Baneasa Bd.Ficusului nr. 23 1 0749.039.541 [email protected] 12 Farmacia Pharma-Plant Titulescu Bld. Nicolae Titulescu nr. 39-49 1 0749.039.704 [email protected] 13 Catena Aerogarii B-dul Aerogarii nr.32, 1 0741.10.6893 [email protected] 14 Catena Grivita 234 Calea Grivitei nr.234, Bl.1, Sc.A, Ap.1, 1 0744.35.9281 [email protected] 15 Catena Titulescu B-dul Nicolae Titulescu nr.10, Bl. 20 , 1 0747.02.0577 [email protected] 16 Catena Ion Mihalache -Turda B-dul Ion Mihalache nr.113 , Bloc 11, 1 0743.00.4177 [email protected] 17 Catena Sala Palatului Str. -

Rahova – Uranus: Un „Cartier Dormitor”?

RAHOVA – URANUS: UN „CARTIER DORMITOR”? BOGDAN VOICU DANA CORNELIA NIŢULESCU ahova–Uranus este o zonă a oraşului Bucureşti situată aproape de centru, însă, ca multe alte cartiere, lipsită aproape complet de orice R viaţă culturală. Studiul de faţă se referă la reprezentările tinerilor din zonă asupra cartierului lor. Folosind date calitative, arătăm că tinerii bucureşteni din Rahova văd în mizerie, aglomeraţie, trafic principalele probleme ale oraşului şi ale zonei în care trăiesc. Investigarea reprezentărilor şi comportamentelor de consum cultural ale tinerilor din cartierul bucureştean Rahova–Uranus relevă caracteristica zonei de a fi, în principal, un „cartier-dormitor”. Oamenii par a veni aici doar ca să locuiască, fiind preocupaţi mai ales în a dormi, a mânca, şi a-şi îndeplini nevoile fiziologice. Materialul de faţă utilizează rezultatele unei cercetări despre modul în care tinerii din zona Rahova – Uranus îşi satisfac nevoia de cultură. Cercetarea, iniţiată şi finanţată de British Council, parte a unui proiect mai larg gestionat de Centrul Internaţional pentru Artă Contemporană1, a fost realizată în octombrie 2006, implicând interviuri semistructurate, cu 26 de tineri între 17 şi 35 de ani. În articolul de faţă ne propunem să contribuim la o mai bună cunoaştere a locuitorilor tineri din zona Rahova – Uranus, identificând nevoile lor de natură culturală, precum şi comportamentele de consum cultural. Ne propunem o descriere, o prezentare de tip documentar a realităţilor observate, explicaţiei şi interpretării fiindu-le alocat un spaţiu mai restrâns. Studiul are în centrul său culturalul nevoia de frumos, cu alte cuvinte acea versiune a culturii în sensul dat de ştiinţele umane2. Suntem interesaţi în ce măsură 1 Mulţumim British Council şi CIAC pentru acceptul de a publica acest material, care utilizează în bună măsură textul raportului de cercetare realizat. -

Directory of Development Organizations

EDITION 2007 VOLUME III.B / EUROPE DIRECTORY OF DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS GUIDE TO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, GOVERNMENTS, PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT AGENCIES, CIVIL SOCIETY, UNIVERSITIES, GRANTMAKERS, BANKS, MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS AND DEVELOPMENT CONSULTING FIRMS Resource Guide to Development Organizations and the Internet Introduction Welcome to the directory of development organizations 2007, Volume III: Europe The directory of development organizations, listing 51.500 development organizations, has been prepared to facilitate international cooperation and knowledge sharing in development work, both among civil society organizations, research institutions, governments and the private sector. The directory aims to promote interaction and active partnerships among key development organisations in civil society, including NGOs, trade unions, faith-based organizations, indigenous peoples movements, foundations and research centres. In creating opportunities for dialogue with governments and private sector, civil society organizations are helping to amplify the voices of the poorest people in the decisions that affect their lives, improve development effectiveness and sustainability and hold governments and policymakers publicly accountable. In particular, the directory is intended to provide a comprehensive source of reference for development practitioners, researchers, donor employees, and policymakers who are committed to good governance, sustainable development and poverty reduction, through: the financial sector and microfinance,