Intra-Urban Spatial Changes Among Women Entrepreneurs in Bucharest (Romania) During Economic Transition (1992-2002)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical GIS: Mapping the Bucharest Geographies of the Pre-Socialist Industry Gabriel Simion*, Alina Mareci, Florin Zaharia, Radu Dumitru

# Gabriel Simion et al. Human Geographies – Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography Vol. 10, No. 2, November 2016 | www.humangeographies.org.ro ISSN–print: 1843–6587 | ISSN–online: 2067–2284 Historical GIS: mapping the Bucharest geographies of the pre-socialist industry Gabriel Simion*, Alina Mareci, Florin Zaharia, Radu Dumitru University of Bucharest, Romania This article aims to map the manner in which the rst industrial units crystalized in Bucharest and their subsequent dynamic. Another phenomenon considered was the way industrial sites grew and propagated and how the rst industrial clusters formed, thus amplifying the functional variety of the city. The analysis was undertaken using Historical GIS, which allowed to integrate elements of industrial history with the location of the most important industrial objectives. Working in GIS meant creating a database with the existing factories in Bucharest, but also those that had existed in different periods. Integrating the historical with the spatial information about industry in Bucharest was preceded by thorough preparations, which included geo-referencing sources (city plans and old maps) and rectifying them. This research intends to serve as an example of how integrating past and present spatial data allows for the analysis of an already concluded phenomenon and also explains why certain present elements got to their current state.. Key Words: historical GIS, GIS dataset, Bucharest. Article Info: Received: September 5, 2016; Revised: October 24, 2016; Accepted: November 15, 2016; Online: November 30, 2016. Introduction The spatial evolution of cities starting with the ending of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th is closely connected to their industrial development. -

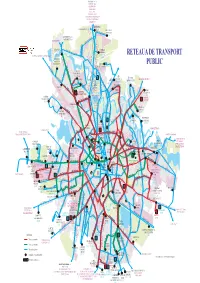

RETEA GENERALA 01.07.2021.Cdr

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 97 204 205 304 261 Sisesti BANEASA RETEAUA DE TRANSPORT R402 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 COMPLEX 112 205 261 97 131 261301 COMERCIAL Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti PUBLIC COLOSSEUM CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 203 335 361 605 780 783 112 R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 Bd. Aerogarii R402 97 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 24 331R436 CFR Str. Alex. Serbanescu 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 DRIDU Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 65 86 112 135 243 Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Bd. Gloriei24 Str. Jiului 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Sos. Chitilei Poligrafiei PIATA PLATFORMA Bd. BucurestiiPajurei Noi 231 243 Str. Peris MEZES 780 783 INDUSTRIALA Str. PRESEI Str.Oi 3 45 65 86 331 243 3 45 382 PASAJ Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 3 41 243 PIPERA 382 DEPOUL R447 R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 i 65 86 97 243 16 36 COLENTINA 131105 203 205 261203 304 231 261 304 330 135 343 n tuz BUCURESTII NOI a R441 R442 R443 c 21 i CARTIER 605 tr 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 DEPOUL Bd. -

People's Advocate

European Network of Ombudsmen THE 2014 REPORT OF PEOPLE’S ADVOCATE INSTITUTION - SUMMARY - In accordance with the provisions of art. 60 of the Constitution and those of art. 5 of Law no. 35/1997 on the organization and functioning of the People's Advocate Institution, republished, with subsequent amendments, the Annual Report concerning the activity of the institution for one calendar year is submitted by the People's Advocate, until the 1st of February of the following year, to Parliament for its debate in the joint sitting of the two Chambers. We present below a summary of the 2014 Report of the People’s Advocate Institution, which has been submitted to Parliament, within the legal deadline provided by Law no. 35/1997. GENERAL VOLUME OF ACTIVITY The overview of the activity in 2014 can be summarized in the following statistics: - 16,841 audiences , in which violations of individuals' rights have been alleged, out of which 2,033 at the headquarters and 14,808 at the territorial offices; - 10,346 complaints registered at the People's Advocate Institution, out of which 6,932 at the headquarters and 3,414 at the territorial offices; Of these, a total of 7,703 complaints were sent to the People's Advocate on paper, 2,551 by email, and 92 were received from abroad. - 8,194 calls recorded by the dispatcher service, out of which 2,504 at the headquarters and 5,690 at the territorial offices; - 137 investigations conducted by the People's Advocate Institution, out of which 33 at the headquarters and 104 at the regional offices; - 56 ex officio -

Title of Paper

Noise pollution generated by road traffic in Bucharest Maria Pătroescu University of Bucharest, Centre for Environmental Research, Bucharest, Romania Cristian Iojă, Viorel Popescu, Radu Necşuliu University of Bucharest, Centre for Environmental Research, Bucharest, Romania ABSTRACT: Through the observations recorded by the Environmental Research Centre, University of Bu- charest, there can be noticed a significant level of noise pollution in Bucharest, caused mainly by the increase of the generating sources and the lack of antiphonic protection measures. The measurements realized in dif- ferent spots (intense traffic streets, industrial platforms, residential areas, market places) indicated that the highest values of the continuous equivalent acoustic level (Leq) appear on the 1st and 2nd category roads, where the heavy traffic is intense. The recorded Leq values were between 65 - 75 dB (A) for the 1st and 2nd category roads, frequently overpassing the maximum admitted level (70 dB(A)). In order to reduce the noise pollution it is necessary to diminish the noise level at the sources and to apply antiphonic protection measures (rehabilitation of forest protection belts, of the roads and tram lines, deviation of heavy traffic etc.). RÉSUMÉ : Par les observations enregistrées par le Centre de Recherche Environnemental de l'Université de Bucarest, on note un niveau significatif de nuisances sonores à Bucarest, causées principalement par l'aug- mentation des sources de production et le manque de mesures de protection antiphoniques. Les mesures effec- tuées dans divers lieux (des rues à forte circulation, des plates-formes industrielles, des secteurs résidentiels, des places de marché) ont indiqué que les valeurs les plus hautes du niveau équivalent acoustique (Leq) conti- nu apparaissent sur les routes de 1ère et 2ème catégorie, où le trafic lourd est intense. -

Download This PDF File

THE SOCIO-SPATIAL DIMENSION OF THE BUCHAREST GHETTOS Viorel MIONEL Silviu NEGUŢ Viorel MIONEL Assistant Professor, Department of Economics History and Geography, Faculty of International Business and Economics, Academy of Economic Studies, Bucharest, Romania Tel.: 0040-213-191.900 Email: [email protected] Abstract Based on a socio-spatial analysis, this paper aims at drawing the authorities’ attention on a few Bucharest ghettos that occurred after the 1990s. Silviu NEGUŢ After the Revolution, Bucharest has undergone Professor, Department of Economics History and Geography, many socio-spatial changes. The modifications Faculty of International Business and Economics, Academy of that occurred in the urban perimeter manifested Economic Studies Bucharest, Romania in the technical and urban dynamics, in the urban Tel.: 0040-213-191.900 infrastructure, and in the socio-economic field. The Email: [email protected] dynamics and the urban evolution of Bucharest have affected the community life, especially the community homogeneity intensely desired during the communist regime by the occurrence of socially marginalized spaces or ghettos as their own inhabitants call them. Ghettos represent an urban stain of color, a special morphologic framework. The Bucharest “ghettos” appeared by a spatial concentration of Roma population and of poverty in zones with a precarious infrastructure. The inhabitants of these areas (Zăbrăuţi, Aleea Livezilor, Iacob Andrei, Amurgului and Valea Cascadelor) are somehow constrained to live in such spaces, mainly because of lack of income, education and because of their low professional qualification. These weak points or handicaps exclude the ghetto population from social participation and from getting access to urban zones with good habitations. -

Trasee De Noapte

PROGRAMUL DE TRANSPORT PENTRU RETEAUA DE AUTOBUZE - TRASEE DE NOAPTE Plecari de la capete de Linia Nr Numar vehicule Nr statii TRASEU CAPETE lo traseu Lungime c 23 00:30 1 2 03:30 4 5 Prima Ultima Dus: Şos. Colentina, Şos. Mihai Bravu, Bd. Ferdinand, Şos. Pantelimon, Str. Gǎrii Cǎţelu, Str. N 101 Industriilor, Bd. Basarabia, Bd. 1 Dus: Decembrie1918 0 2 2 0 2 0 0 16 statii Intors: Bd. 1 Decembrie1918, Bd. 18.800 m Basarabia, Str. Industriilor, Str. Gǎrii 88 Intors: Cǎţelu, Şos. Pantelimon, Bd. 16 statii Ferdinand, Şos. Mihai Bravu, Şos. 18.400 m Colentina. Terminal 1: Pasaj Colentina 00:44 03:00 Terminal 2: Faur 00:16 03:01 Dus: Piata Unirii , Bd. I. C. Bratianu, Piata Universitatii, Bd. Carol I, Bd. Pache Protopopescu, Sos. Mihai Bravu, Str. Vatra Luminoasa, Bd. N102 Pierre de Coubertin, Sos. Iancului, Dus: Sos. Pantelimon 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 19 statii Intors: Sos. Pantelimon, Sos. Iancului, 8.400 m Bd. Pierre de Coubertin, Str. Vatra 88 Intors: Luminoasa, Sos. Mihai Bravu, Bd. 16 statii Pache Protopopescu, Bd. Carol I, 8.600 m Piata Universitatii, Bd. I. C. Bratianu, Piata Unirii. Terminal 1: Piata Unirii 2 23:30 04:40 Terminal 2: Granitul 22.55 04:40 Dus: Bd. Th. Pallady, Bd. Camil Ressu, Cal. Dudeşti, Bd. O. Goga, Str. Nerva Traian, Cal. Văcăreşti, Şos. Olteniţei, Str. Ion Iriceanu, Str. Turnu Măgurele, Str. Luică, Şos. Giurgiului, N103 Piaţa Eroii Revoluţiei, Bd. Pieptănari, us: Prelungirea Ferentari 0 2 1 0 2 0 0 24 statii Intors: Prelungirea Ferentari, , Bd. -

Lista Farmaciilor DONA Unde Se Poate Plăti În RATE CU 0% DOBÂNDĂ Prin Cardurile Participante BRD Finance Mastercard Denumire Adresa Dona 37 Ploiesti 3 Str

Lista farmaciilor DONA unde se poate plăti în RATE CU 0% DOBÂNDĂ prin cardurile participante BRD Finance MasterCard Denumire Adresa Dona 37 Ploiesti 3 Str. Bibescu Voda, nr. 1 Dona 1 Decembrie Bd. 1 Decembrie 1918, Nr.25,Bl.U6,Sect.3,Bucuresti Dona 1 Pieptanari Sos. Viilor, nr. 94, sec. 5, Bucuresti DONA 10 VITAN Calea Vitan, nr. 199 DONA 101 L.REBREANU Str. Liviu Rebreanu, nr. 13A, bl. N20 DONA 102 CAMIL RESSU 2 Bd. Camil Ressu nr. 4, bl. 5 DONA 109 ALEXANDRIEI 2 Sos. Alexandriei nr. 8, bl. L3, parter DONA 11 PANTELIMON Sos. Pantelimon, nr. 354, bl. 2 DONA 115 MOGHIOROS Drumul Taberei nr. 44 DONA 116 TH.PALLADY Bd. Theodor Pallady, nr. 27, bl. G3 bis DONA 12 MIHAI BRAVU Sos. Mihai Bravu, nr.120, bl. D28 Dona 125 Craiova 3 Str. Nicolae Iorga, nr. 112, bl. A62, Cartier Rovine DONA 13 PROGRESULUI Sos. Giurgiului, nr. 103-107 Dona 14 Amzei Str. Mendeleev, nr.21-25 (Piaţa Amzei), sector1, Bucureşti DONA 143 DELFINULUI Sos Pantelimon, 245,bl. 51 DONA 144 RAMNICU-SARAT B-dul Rimnicu Sarat Nr. 17, Bl. 201 DONA 145 BRANCOVEANU Bd. C-tin Brancoveanu, nr. 116, bl. M2 / III DONA 15 OLTENITEI Sos. Oltenitei, nr. 240 DONA 150 BASARABIEI 2 Bd. Basarabia Nr. 118Bl. L13Sc. CAp. 0 DONA 152 STEFAN CEL MARE Stefan cel mare, nr.4, bl 14, sect. 1, DONA 156 TEIUL DOAMNEI Bd. Teiul Doamnei Nr. 12, Bl. 9, Ap. 0 DONA 16 TITAN Bd. Nicolae Grigorescu, nr. 20 DONA 166 CAMIL RESSU 3 Str. Camil Ressu Nr. -

Rahova – Uranus: Un „Cartier Dormitor”?

RAHOVA – URANUS: UN „CARTIER DORMITOR”? BOGDAN VOICU DANA CORNELIA NIŢULESCU ahova–Uranus este o zonă a oraşului Bucureşti situată aproape de centru, însă, ca multe alte cartiere, lipsită aproape complet de orice R viaţă culturală. Studiul de faţă se referă la reprezentările tinerilor din zonă asupra cartierului lor. Folosind date calitative, arătăm că tinerii bucureşteni din Rahova văd în mizerie, aglomeraţie, trafic principalele probleme ale oraşului şi ale zonei în care trăiesc. Investigarea reprezentărilor şi comportamentelor de consum cultural ale tinerilor din cartierul bucureştean Rahova–Uranus relevă caracteristica zonei de a fi, în principal, un „cartier-dormitor”. Oamenii par a veni aici doar ca să locuiască, fiind preocupaţi mai ales în a dormi, a mânca, şi a-şi îndeplini nevoile fiziologice. Materialul de faţă utilizează rezultatele unei cercetări despre modul în care tinerii din zona Rahova – Uranus îşi satisfac nevoia de cultură. Cercetarea, iniţiată şi finanţată de British Council, parte a unui proiect mai larg gestionat de Centrul Internaţional pentru Artă Contemporană1, a fost realizată în octombrie 2006, implicând interviuri semistructurate, cu 26 de tineri între 17 şi 35 de ani. În articolul de faţă ne propunem să contribuim la o mai bună cunoaştere a locuitorilor tineri din zona Rahova – Uranus, identificând nevoile lor de natură culturală, precum şi comportamentele de consum cultural. Ne propunem o descriere, o prezentare de tip documentar a realităţilor observate, explicaţiei şi interpretării fiindu-le alocat un spaţiu mai restrâns. Studiul are în centrul său culturalul nevoia de frumos, cu alte cuvinte acea versiune a culturii în sensul dat de ştiinţele umane2. Suntem interesaţi în ce măsură 1 Mulţumim British Council şi CIAC pentru acceptul de a publica acest material, care utilizează în bună măsură textul raportului de cercetare realizat. -

Component 1. Elaboration of Bucharest's Iuds, Capital

ROMANIA Reimbursable Advisory Services Agreement on the Bucharest Urban Development Program (P169577) COMPONENT 1. ELABORATION OF BUCHAREST’S IUDS, CAPITAL INVESTMENT PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT Output 3. Urban context and identification of key local issues and needs, and visions and objectives of IUDS and Identification of a long list of projects. Chapter 3. Spatial and Functional Profile March 2021 DISCLAIMER This report is a product of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/the World Bank. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. This report does not necessarily represent the position of the European Union or the Romanian Government. COPYRIGHT STATEMENT The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable laws. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with the complete information to either: (i) the Municipality of Bucharest (Bd. Regina Elisabeta 47, Bucharest, Romania); or (ii) the World Bank Group Romania (Str. Vasile Lascăr 31, et. 6, Sector 2, Bucharest, Romania). This report was delivered in March 2021 under the Reimbursable Advisory Services Agreement on the Bucharest Urban Development Program, concluded between the Municipality of Bucharest and the -

Romania 2019 Human Rights Report

ROMANIA 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Romania is a constitutional republic with a democratic, multiparty parliamentary system. The bicameral parliament consists of the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies, both elected by popular vote. Observers considered presidential elections held on November 10 and 24 and parliamentary elections in 2016 to have been generally free and fair and without significant irregularities. The Ministry of Internal Affairs is responsible for the General Inspectorate of the Romanian Police, the gendarmerie, border police, the General Directorate for Internal Protection (DGPI), and the Directorate General for Anticorruption (DNA). The DGPI has responsibility for intelligence gathering, counterintelligence, and preventing and combatting vulnerabilities and risks that could seriously disrupt public order or target Ministry of Internal Affairs operations. The minister of interior appoints the head of DGPI. The Romanian Intelligence Service (SRI), the domestic security agency, investigates terrorism and national security threats. The president nominates and the parliament confirms the SRI director. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over SRI and the security agencies that reported to the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Significant human rights issues included: police violence against Roma; endemic official corruption; law enforcement authorities condoning violence against women and girls; and abuse against institutionalized persons with disabilities. The judiciary took steps to prosecute and punish officials who committed abuses, but authorities did not have effective mechanisms to do so and delayed proceedings involving alleged police abuse and corruption, with the result that many of the cases ended in acquittals. Impunity for perpetrators of human rights abuses was a continuing problem. Section 1. Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from: a. -

Cfr Progresul →Depoul Militari Vezi În Modul Website

Orar & hartă linie 25 tramvai 25 Cfr Progresul →Depoul Militari Vezi În Modul Website Linia 25tramvai (Cfr Progresul →Depoul Militari) are 2 rute. Pentru zilele din săptămână. orele de funcționare sunt: (1) Cfr Progresul →Depoul Militari: 4:20 - 22:20 (2) Depoul Militari →Cfr Progresul: 4:05 - 23:00 Folosește Aplicația Moovit pentru a găsi cea mai apropiată 25 tramvai stație din împrejurimi și a a≈a când 25 tramvai sosește. Direcții: Cfr Progresul →Depoul Militari Orar 25 tramvai 35 stații Cfr Progresul →Depoul Militari Orar rută: VEZI ORAR luni 4:20 - 22:20 marți 4:20 - 22:20 Cfr Progresul Drumul Bercenarului, București miercuri 4:20 - 22:20 Răducanu Cristea joi 4:20 - 22:20 236 Șoseaua Giurgiului, București vineri 4:20 - 22:20 Anghel Nuțu sâmbătă 4:20 - 22:40 261 Sos. Giurgiului, București duminică 4:20 - 22:40 Luică 239 Sos. Giurgiului, București Cimitirul Evreiesc 162 Sos. Giurgiului, București Info 25 tramvai Direcții: Cfr Progresul →Depoul Militari Drumul Găzarului Opriri: 35 Drumul Găzarului, București Durata călătoriei: 58 min Sumar linie: Cfr Progresul, Răducanu Cristea, Toporași Anghel Nuțu, Luică, Cimitirul Evreiesc, Drumul Găzarului, Toporași, Piața Progresul, Muzeul Piața Progresul Bacovia, Șura Mare, Piaţa Eroii Revoluţiei Ⓜ②, 97 Sos. Giurgiului, București Ștefan Hepiteș, Dr. Constantin Istrati, Spătarul Preda, Calea Rahovei, Inox, Calea 13 Septembrie, Muzeul Bacovia Cartier Panduri, Piața Danny Huwe Ⓜ⑤, Bd. Vasile 47 Șoseaua Giurgiului, București Milea, Sibiu, Sergent Moise, Brașov, Compasului, Romancierilor, Frigocom, Valea Oltului, Radox, Valea Șura Mare Cascadelor, Cfr Cotroceni, Cesarom, Urbis, Sc Vest 2 Șoseaua Giurgiului, București Ⓜ③, Inscut, Depoul Militari Piaţa Eroii Revoluţiei Ⓜ② 100 Sos. -

Hidden Communities Ferentari

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ZENODO Florin BOTONOGU ‐ coordinator ‐ HIDDEN COMMUNITIES FERENTARI Authors: Florin BOTONOGU (coordinator) Simona Maria STĂNESCU Victor NICOLĂESCU Florina PRESADA Cătălin BERESCU Valeriu NICOLAE Adrian Marcel IANCU Gabriel OANCEA Andreea Simona Marcela FAUR Diana ŞERBAN Daniela NICOLĂESCU © Bucharest, Romania CNCSIS: cod 045/2006 Editor: Valeriu IOAN‐FRANC Graphic design, templates and typesetting: Luminița LOGIN Cover by: Nicolae LOGIN All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher ISBN 978‐973‐618‐287‐9 Apărut 2011 THE GHETTO AND THE DISADVANTAGED HOUSING AREA (DHA) – LIVEZILOR ALLEY Cătălin BERESCU Brief Urban and Architectural Description Livezilor Alley is a sub‐district area, developed next to Prelungirea Ferentari, behind a first row of short streets, which are typical Bucharest slums, with short and dense buildings set out on small lots. The Livezilor area is tangent to the slums through School 136, with Vâltoarei Street serving as its axis and Tunsu Petre, Surianu and Livezilor streets, as well as the fence of the Electromagnetica warehouse on Lacul Bucura Street serving as its borders. This area is created based on the principles of free urbanism, the alley covering in fact a surface of 26 apartment buildings, one park and one school, on the right side of Vâltoarei Street and 20 apartment buildings and one kindergarten on the left. From an administrative point of view, the alley itself has 30 apartment buildings, while the rest of them are on other streets, although they are part of the same ensemble.