Reprinted from Physics World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revisiting One World Or None

Revisiting One World or None. Sixty years ago, atomic energy was new and the world was still reverberating from the shocks of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Immediately after the end of the Second World War, the first instinct of the administration and Congress was to protect the “secret” of the atomic bomb. The atomic scientists—what today would be called nuclear physicists— who had worked on the Manhattan project to develop atomic bombs recognized that there was no secret, that any technically advanced nation could, with adequate resources, reproduce what they had done. They further believed that when a single aircraft, eventually a single missile, armed with a single bomb could destroy an entire city, no defense system would ever be adequate. Given this combination, the world seemed headed for a period of unprecedented danger. Many of the scientists who had worked on the Manhattan Project felt a special responsibility to encourage a public debate about these new and terrifying products of modern science. They formed an organization, the Federation of Atomic Scientists, dedicated to avoiding the threat of nuclear weapons and nuclear proliferation. Convinced that neither guarding the nuclear “secret” nor any defense could keep the world safe, they encouraged international openness in nuclear physics research and in the expected nuclear power industry as the only way to avoid a disastrous arms race in nuclear weapons. William Higinbotham, the first Chairman of the Association of Los Alamos Scientists and the first Chairman of the Federation of Atomic Scientists, wanted to expand the organization beyond those who had worked on the Manhattan Project, for two reasons. -

![I. I. Rabi Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered Tue Apr](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8589/i-i-rabi-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-rendered-tue-apr-428589.webp)

I. I. Rabi Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered Tue Apr

I. I. Rabi Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 1992 Revised 2010 March Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms998009 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm89076467 Prepared by Joseph Sullivan with the assistance of Kathleen A. Kelly and John R. Monagle Collection Summary Title: I. I. Rabi Papers Span Dates: 1899-1989 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1945-1968) ID No.: MSS76467 Creator: Rabi, I. I. (Isador Isaac), 1898- Extent: 41,500 items ; 105 cartons plus 1 oversize plus 4 classified ; 42 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Physicist and educator. The collection documents Rabi's research in physics, particularly in the fields of radar and nuclear energy, leading to the development of lasers, atomic clocks, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and to his 1944 Nobel Prize in physics; his work as a consultant to the atomic bomb project at Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory and as an advisor on science policy to the United States government, the United Nations, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization during and after World War II; and his studies, research, and professorships in physics chiefly at Columbia University and also at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The new prophet : Harold C. Urey, scientist, atheist, and defender of religion Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3j80v92j Author Shindell, Matthew Benjamin Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The New Prophet: Harold C. Urey, Scientist, Atheist, and Defender of Religion A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History (Science Studies) by Matthew Benjamin Shindell Committee in charge: Professor Naomi Oreskes, Chair Professor Robert Edelman Professor Martha Lampland Professor Charles Thorpe Professor Robert Westman 2011 Copyright Matthew Benjamin Shindell, 2011 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Matthew Benjamin Shindell is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ___________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2011 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………………...... iii Table of Contents……………………………………………………………………. iv Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………. -

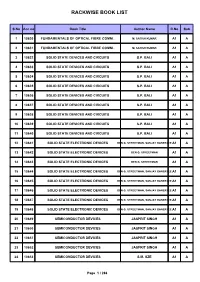

Rackwise Book List

RACKWISE BOOK LIST S.No Acc no Book Title Author Name R.No Sub 1 10630 FUNDAMENTALS OF OPTICAL FIBRE COMM.. M. SATISH KUMAR A1 A 2 10631 FUNDAMENTALS OF OPTICAL FIBRE COMM.. M. SATISH KUMAR A1 A 3 10632 SOLID STATE DEVICES AND CIRCUITS S.P. BALI A1 A 4 10633 SOLID STATE DEVICES AND CIRCUITS S.P. BALI A1 A 5 10634 SOLID STATE DEVICES AND CIRCUITS S.P. BALI A1 A 6 10635 SOLID STATE DEVICES AND CIRCUITS S.P. BALI A1 A 7 10636 SOLID STATE DEVICES AND CIRCUITS S.P. BALI A1 A 8 10637 SOLID STATE DEVICES AND CIRCUITS S.P. BALI A1 A 9 10638 SOLID STATE DEVICES AND CIRCUITS S.P. BALI A1 A 10 10639 SOLID STATE DEVICES AND CIRCUITS S.P. BALI A1 A 11 10640 SOLID STATE DEVICES AND CIRCUITS S.P. BALI A1 A 12 10641 SOLID STATE ELECTRONIC DEVICES BEN G. STREETMAN, SANJAY BANERJEE A1 A 13 10642 SOLID STATE ELECTRONIC DEVICES BEN G. STREETMAN A1 A 14 10643 SOLID STATE ELECTRONIC DEVICES BEN G. STREETMAN A1 A 15 10644 SOLID STATE ELECTRONIC DEVICES BEN G. STREETMAN, SANJAY BANERJEE A1 A 16 10645 SOLID STATE ELECTRONIC DEVICES BEN G. STREETMAN, SANJAY BANERJEE A1 A 17 10646 SOLID STATE ELECTRONIC DEVICES BEN G. STREETMAN, SANJAY BANERJEE A1 A 18 10647 SOLID STATE ELECTRONIC DEVICES BEN G. STREETMAN, SANJAY BANERJEE A1 A 19 10648 SOLID STATE ELECTRONIC DEVICES BEN G. STREETMAN, SANJAY BANERJEE A1 A 20 10649 SEMICONDUCTOR DEVICES JASPRIT SINGH A1 A 21 10650 SEMICONDUCTOR DEVICES JASPRIT SINGH A1 A 22 10651 SEMICONDUCTOR DEVICES JASPRIT SINGH A1 A 23 10652 SEMICONDUCTOR DEVICES JASPRIT SINGH A1 A 24 10653 SEMICONDUCTOR DEVICES S.M. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: the PRINCIPAL UNCERTAINTY: U.S

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE PRINCIPAL UNCERTAINTY: U.S. ATOMIC INTELLIGENCE, 1942-1949 Vincent Jonathan Houghton, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida Department of History The subject of this dissertation is the U. S. atomic intelligence effort against both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in the period 1942-1949. Both of these intelligence efforts operated within the framework of an entirely new field of intelligence: scientific intelligence. Because of the atomic bomb, for the first time in history a nation’s scientific resources – the abilities of its scientists, the state of its research institutions and laboratories, its scientific educational system – became a key consideration in assessing a potential national security threat. Considering how successfully the United States conducted the atomic intelligence effort against the Germans in the Second World War, why was the United States Government unable to create an effective atomic intelligence apparatus to monitor Soviet scientific and nuclear capabilities? Put another way, why did the effort against the Soviet Union fail so badly, so completely, in all potential metrics – collection, analysis, and dissemination? In addition, did the general assessment of German and Soviet science lead to particular assumptions about their abilities to produce nuclear weapons? How did this assessment affect American presuppositions regarding the German and Soviet strategic threats? Despite extensive historical work on atomic intelligence, the current historiography has not adequately addressed these questions. THE PRINCIPAL UNCERTAINTY: U.S. ATOMIC INTELLIGENCE, 1942-1949 By Vincent Jonathan Houghton Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2013 Advisory Committee: Professor Jon T. -

Regimmotstånd? – ”Deutche Physik” Affären

KOSMOS 2011: 79–105, Svenska fysikersamfundet Regimmotstånd? Deutsche Physik- affären1 Stephan Schwarz Sammanfattning I redogörelser för den vetenskaplig-tekniska forskningens vill- kor i Tredje riket har Deutsche Physik-affären länge framhål- lits som paradexempel på forskarsamhällets opposition mot nationalsocialistisk ideologi. Det var fysikpristagarna Philipp Lenard och Johannes Stark som redan under Weimarrepubli- ken förkunnade en rasistisk ”kunskapsteori” som skilde mellan pragmatisk (experimentell, kreativ, arisk) och dogmatisk (spe- kulativ, destruktiv, judisk) fysik, den senare karakteriserad av en ”artfrämmande” mentalitet. I NS-staten drev framför allt Stark en kampanj i politiskt orienterade media, där han angrep den moderna teoretiska fysiken och dess mest framträdande person- ligheter, som Planck och Heisenberg. Deutsche Physik-rörelsen, som utnyttjade intressemotsättningar i makteliten för att till- skansa sig forskningspolitisk dominans, fick bara begränsat inflytande, och ebbade ut redan före kriget. Det var inte fråga om ideologiskt motstånd mot regimen – båda lägren använde NS-retorik, inte minst antisemitisk fraseologi för att bevisa sin politiska tillförlitlighet. Det ifrågasätts om Heisenbergs roll, framför allt i Schwarze Korps-incidenten, inte har framställts som överdrivet dramatisk och betydelsefull. I efterkrigstiden blev DP-affären en välkommen resurs för självpromoverande narrativ om motstånd mot ”partifysik” eller mer allmänt regim- motstånd. Bakgrund Det vi i dag betraktar som mänsklig I efterkrigstidens skildringar av F&U-samhällets hållningar till kultur, det vi ser av konst, vetenskap NS-staten framhålls ofta två episoder som exempel på ideolo- och teknik, är uteslutande Arierns 3 förtjänst. Just detta faktum leder giskt motstånd: Haber-minnesseminariet och Deutsche Physik- till den inte illa underbyggda slut- affären. Numera råder enighet bland vetenskapshistoriker att satsen, att Han ensam har byggt ingetdera av fallen handlade om ideologiskt motstånd. -

Wiederaufbau Ohne Wiederkehr

MÜNCHNER ZENTRUM FÜR WISSENSCHAFTS- UND TECHNIKGESCHICHTE MUNICH CENTER FOR THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY ARBEITSPAPIER Working Paper Arne Schirrmacher Wiederaufbau ohne Wiederkehr Die Physik in Deutschland in den Jahren nach 1945 und die historiographische Problematik des Remigrationskonzepts DEUTSCHES LUDWIG- TECHNISCHE UNIVERSITÄT MUSEUM MAXIMILIANS- HOMEPAGE UNIVERSITÄT DER BUNDESWEHR MÜNCHEN UNIVERSITÄT WWW.MZWTG.MWN.DE MÜNCHEN MÜNCHEN Schirrmacher: Wiederaufbau ohne Wiederkehr Seite 1 Arne Schirrmacher Wiederaufbau ohne Wiederkehr Die Physik in Deutschland in den Jahren nach 1945 und die historiographische Problematik des Remigrationskonzepts* Hätten Sie den Mut nach Deutschland zurückzukommen, wenn Heisenberg definitiv nicht zu haben ist?1 Nach den umfangreichen Forschungen zur Wissenschaftsemigration ist seit etwa zehn Jahren auch die Remigration von Intellektuellen und Forschern nach 1945 stärker in den Blick der historischen Forschung geraten.2 Den Akzent, den ich in dieser Diskussion mit meinem Beitrag setzen möchte, wird aus der Gegenüberstellung meines Titels mit dem eines 1997 von Klaus-Dieter Krohn und Patrik von zur Mühlen herausgegebenen Sammelband deutlich: Krohn und von zur Mühlen sprachen von "Rückkehr und Aufbau nach 1945" und schrieben im Rückentext des Bandes: "Und zurückgekehrte Gelehrte sorgten dafür, dass Deutschland wieder intellektuellen Anschluss an die internationale Wissenschaftsgemeinschaft fand." Ihr Untertitel machte freilich deutlich, dass "Deutsche Remigranten im öffentlichen Leben" im Zentrum des Interesses standen, somit der Blick von außen auf die Wissenschaft gewählt wur- de.3 So richtig diese Bewertung für einige Musterbeispiele von Rückkehrern ist, die mit neuen wissenschaftlichen Ideen oder kulturellen Erfahrungen im Gepäck kamen, wie etwa Max Horkheimer und Theodor Adorno, Bert Brecht oder Günther Anders, so begrenzt ist doch ihre * Vortrag gehalten auf der Tagung "Kontinuitäten und Diskontinuitäten in der Wissenschaftsgeschichte im 20. -

Newly Opened Correspondence Illuminates Einstein's Personal Life

CENTER FOR HISTORY OF PHYSICS NEWSLETTER Vol. XXXVIII, Number 2 Fall 2006 One Physics Ellipse, College Park, MD 20740-3843, Tel. 301-209-3165 Newly Opened Correspondence Illuminates Einstein’s Personal Life By David C. Cassidy, Hofstra University, with special thanks to Diana Kormos Buchwald, Einstein Papers Project he Albert Einstein Archives at the Hebrew University of T Jerusalem recently opened a large collection of Einstein’s personal correspondence from the period 1912 until his death in 1955. The collection consists of nearly 1,400 items. Among them are about 300 letters and cards written by Einstein, pri- marily to his second wife Elsa Einstein, and some 130 letters Einstein received from his closest family members. The col- lection had been in the possession of Einstein’s step-daughter, Margot Einstein, who deposited it with the Hebrew University of Jerusalem with the stipulation that it remain closed for twen- ty years following her death, which occurred on July 8, 1986. The Archives released the materials to public viewing on July 10, 2006. On the same day Princeton University Press released volume 10 of The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, con- taining 148 items from the collection through December 1920, along with other newly available correspondence. Later items will appear in future volumes. “These letters”, write the Ein- stein editors, “provide the reader with substantial new source material for the study of Einstein’s personal life and the rela- tionships with his closest family members and friends.” H. Richard Gustafson playing with a guitar to pass the time while monitoring the control room at a Fermilab experiment. -

Att Gilla Läget Stephan Schwarz Rollspel, Anpassning Och Rationalisering Bland Fysiker I Tredje Riket, Med Utblick Mot Det Omgivande F&U Systemet

KOSMOS 2013: 117-179 Svenska fysikersamfundet Att gilla läget Stephan Schwarz Rollspel, anpassning och rationalisering bland fysiker i Tredje Riket, med utblick mot det omgivande F&U systemet Del 2: ”...såsom i en spegel” – den tidiga efterkrigstiden 1. Sammanfattning Det nationalsocialistiska maktövertagandet (30 januari 1933) möttes i vida kretsar med entusiasm, även inom forskarsamhäl- let. Tydliga varnings-signaler bortförklarades i början med tal om stabilisering i en övergångsfas och om patriotisk plikt att delta i återupprättandet av fosterlandets roll. Mycket snart stod det klart att, för att klara sig i NS-staten måste man till varje pris undvika att betraktas som ”politiskt otillförlitlig”. Oberoende av hur man mentalt ställde sig till NS-ideologi och -politik var man tvungen att uppträda så att man kunde betraktas som lojal mot systemet (politiskt tillförlitlig), dvs att åtminstone spela rollen som ”virtuell nationalsocialist” (VNS). Med en arsenal av meta- forer och historicistiska och moralfilosofiska argument försökte man övertyga inte minst sig själv om att ha träffat moraliskt rik- tiga val under givna omständigheter (se Sc13). I denna andra del diskuteras den tidiga efterkrigstidens behov av ansvarsfrihet för verksamhet i NS-staten. Som stöd i de av ockupationsmak- terna krävda denazifieringsförfarandena utbildades ett idiom för formulering av renhetsförklaringar (s.k. Persilscheine) som omfattade dekontextualisering, målriktad selektion och presen- tation av fakta, medvetet oklara begrepp och vilseledande eller ogiltiga argument och slutsatser. Anmärkningsvärt många av dessa uttalanden för ”vitvaskning” går bortom gränserna för det i forsknings-sammanhang kategoriska kravet på intellektu- ell hederlighet. En analys av försvarsargumenten med hjälp av teorin för Cognitive Dissonance Reduction (CDR) och retoriska ”informal fallacies” (här kallade ”övertalningsfällor”) ger en fördjupad förståelse av den bakomliggande mentaliteten. -

Sir Arthur Eddington and the Foundations of Modern Physics

Sir Arthur Eddington and the Foundations of Modern Physics Ian T. Durham Submitted for the degree of PhD 1 December 2004 University of St. Andrews School of Mathematics & Statistics St. Andrews, Fife, Scotland 1 Dedicated to Alyson Nate & Sadie for living through it all and loving me for being you Mom & Dad my heroes Larry & Alice Sharon for constant love and support for everything said and unsaid Maggie for making 13 a lucky number Gram D. Gram S. for always being interested for strength and good food Steve & Alice for making Texas worth visiting 2 Contents Preface … 4 Eddington’s Life and Worldview … 10 A Philosophical Analysis of Eddington’s Work … 23 The Roaring Twenties: Dawn of the New Quantum Theory … 52 Probability Leads to Uncertainty … 85 Filling in the Gaps … 116 Uniqueness … 151 Exclusion … 185 Numerical Considerations and Applications … 211 Clarity of Perception … 232 Appendix A: The Zoo Puzzle … 268 Appendix B: The Burying Ground at St. Giles … 274 Appendix C: A Dialogue Concerning the Nature of Exclusion and its Relation to Force … 278 References … 283 3 I Preface Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity is perhaps the most significant development in the history of modern cosmology. It turned the entire field of cosmology into a quantitative science. In it, Einstein described gravity as being a consequence of the geometry of the universe. Though this precise point is still unsettled, it is undeniable that dimensionality plays a role in modern physics and in gravity itself. Following quickly on the heels of Einstein’s discovery, physicists attempted to link gravity to the only other fundamental force of nature known at that time: electromagnetism. -

Memorial Tributes: Volume 9

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://nap.edu/10094 SHARE Memorial Tributes: Volume 9 DETAILS 326 pages | 6 x 9 | HARDBACK ISBN 978-0-309-07411-7 | DOI 10.17226/10094 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK National Academy of Engineering FIND RELATED TITLES Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 9 i Memorial Tributes NATIONAL ACADEMY OF ENGINEERING Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 9 ii Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 9 iii NATIONAL ACADEMY OF ENGINEERING OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Memorial Tributes Volume 9 NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS Washington, D.C. 2001 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 9 iv International Standard Book Number 0–309–07411–8 International Standard Serial Number 1075–8844 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 20–1088636 Additional copies of this publication are available from: National Academy Press 2101 Constitution Avenue, N.W. Box 285 Washington, D.C. 20055 800– 624–6242 or 202–334–3313 (in the Washington Metropolitan Area) B-467 Copyright 2001 by the National Academy of Sciences. -

Appendix a I

Appendix A I Appendix A Professional Institutions and Associations AVA: Aerodynamische Versuchsanstalt (see under --+ KWIS) DFG: Deutsche Forschungs-Gemeinschaft (previously --+ NG) German Scientific Research Association. Full title: Deutsche Gemeinschaft zur Erhaltung und Forderung der Forschung (German Association for the Support and Advancement of Sci entific Research). Successor organization to the --+ NG, which was renamed DFG unofficially since about 1929 and officially in 1937. During the terms of its presidents: J. --+ Stark (June 1934-36); R. --+ Mentzel (Nov. 1936-39) and A. --+ Esau (1939-45), the DFG also had a dom inant influence on the research policy of the --+ RFR. It was funded by government grants in the millions and smaller contributions by the --+ Stifterverband. Refs.: ~1entzel [1940]' Stark [1943]c, Zierold [1968], Nipperdey & Schmugge [1970]. DGtP: Deutsche Gesellschaft fiir technische Physik German Society of Technical Physics. Founded on June 6, 1919 by Georg Gehlhoff as an alternative to the --+ DPG with a total of 13 local associations and its own journal --+ Zeitschrift fUr technische Physik. Around 1924 the DGtP had approximately 3,000 members, thus somewhat more than the DPG, but membership fell by 1945 to around 1,500. Chairmen: G. Gehlhoff (1920-31); K. --+ Mey (1931-45). Refs.: Gehlhoff et al. [1920]' Ludwig [1974], Richter [1977], Peschel (Ed.) [1991]' chap. 1, Heinicke [1985]' p. 43, Hoffmann & Swinne [1994]. DPG: Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft German Physical Society. Founded in 1899 a national organization at to succeed the Berlin Physical Society, which dates back to 1845. The Society issued regular biweekly proceedings, reports (Berichte) on the same, as well as the journal: Fortschritte der Physik (since 1845).