Sir Arthur Eddington and the Foundations of Modern Physics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cathode Rays 89 Cathode Rays

Cathode Rays 89 Cathode Rays Theodore Arabatzis C The detection of cathode rays was a by-product of the investigation of the discharge of electricity through rarefied gases. The latter phenomenon had been studied since the early eighteenth century. By the middle of the nineteenth century it was known that the passage of electricity through a partly evacuated tube produced a glow in the gas, whose color depended on its chemical composition and its pressure. Below a certain pressure the glow assumed a stratified pattern of bright and dark bands. During the second half of the nineteenth century the discharge of electricity through gases became a topic of intense exploratory experimentation, primarily in Germany [21]. In 1855 the German instrument maker Heinrich Geißler (1815– 1879) manufactured improved vacuum tubes, which made possible the isolation and investigation of cathode rays [23]. In 1857 Geissler’s tubes were employed by Julius Pl¨ucker (1801–1868) to study the influence of a magnet on the electrical dis- charge. He observed various complex and striking phenomena associated with the discharge. Among those phenomena were a “light which appears about the negative electrode” and a fluorescence in the glass of the tube ([9], pp. 122, 130). The understanding of those phenomena was advanced by Pl¨ucker’s student and collaborator, Johann Wilhelm Hittorf (1824–1914), who observed that “if any ob- ject is interposed in the space filled with glow-light [emanating from the negative electrode], it throws a sharp shadow on the fluorescent side” ([5], p. 117). This effect implied that the “rays” emanating from the cathode followed a straight path. -

Philosophy and the Physicists Preview

L. Susan Stebbing Philosophy and the Physicists Preview il glifo ebooks ISBN: 9788897527466 First Edition: December 2018 (A) Copyright © il glifo, December 2018 www.ilglifo.it 1 Contents FOREWORD FROM THE EDITOR Note to the 2018 electronic edition PHILOSOPHY AND THE PHYSICISTS Original Title Page PREFACE NOTE PART I - THE ALARMING ASTRONOMERS Chapter I - The Common Reader and the Popularizing Scientist Chapter II - THE ESCAPE OF SIR JAMES JEANS PART II - THE PHYSICIST AND THE WORLD Chapter III - ‘FURNITURE OF THE EARTH’ Chapter IV - ‘THE SYMBOLIC WORLD OF PHYSICS’ Chapter V - THE DESCENT TO THE INSCRUTABLE Chapter VI - CONSEQUENCES OF SCRUTINIZING THE INSCRUTABLE PART III - CAUSALITY AND HUMAN FREEDOM Chapter VII - THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY NIGHTMARE Chapter VIII - THE REJECTION OF PHYSICAL DETERMINISM Chapter IX - REACTIONS AND CONSEQUENCES Chapter X - HUMAN FREEDOM AND RESPONSIBILITY PART IV - THE CHANGED OUTLOOK Chapter XI - ENTROPY AND BECOMING Chapter XII - INTERPRETATIONS BIBLIOGRAPHY INDEX BACK COVER Susan Stebbing 2 Foreword from the Editor In 1937 Susan Stebbing published Philosophy and the Physicists , an intense and difficult essay, in reaction to reading the works written for the general public by two physicists then at the center of attention in England and the world, James Jeans (1877-1946) and Arthur Eddington (1882- 1944). The latter, as is known, in 1919 had announced to the Royal Society the astronomical observations that were then considered experimental confirmations of the general relativity of Einstein, and who by that episode had managed to trigger the transformation of general relativity into a component of the mass and non-mass imaginary of the twentieth century. -

Rutherford's Nuclear World: the Story of the Discovery of the Nuc

Rutherford's Nuclear World: The Story of the Discovery of the Nuc... http://www.aip.org/history/exhibits/rutherford/sections/atop-physic... HOME SECTIONS CREDITS EXHIBIT HALL ABOUT US rutherford's explore the atom learn more more history of learn about aip's nuclear world with rutherford about this site physics exhibits history programs Atop the Physics Wave ShareShareShareShareShareMore 9 RUTHERFORD BACK IN CAMBRIDGE, 1919–1937 Sections ← Prev 1 2 3 4 5 Next → In 1962, John Cockcroft (1897–1967) reflected back on the “Miraculous Year” ( Annus mirabilis ) of 1932 in the Cavendish Laboratory: “One month it was the neutron, another month the transmutation of the light elements; in another the creation of radiation of matter in the form of pairs of positive and negative electrons was made visible to us by Professor Blackett's cloud chamber, with its tracks curled some to the left and some to the right by powerful magnetic fields.” Rutherford reigned over the Cavendish Lab from 1919 until his death in 1937. The Cavendish Lab in the 1920s and 30s is often cited as the beginning of modern “big science.” Dozens of researchers worked in teams on interrelated problems. Yet much of the work there used simple, inexpensive devices — the sort of thing Rutherford is famous for. And the lab had many competitors: in Paris, Berlin, and even in the U.S. Rutherford became Cavendish Professor and director of the Cavendish Laboratory in 1919, following the It is tempting to simplify a complicated story. Rutherford directed the Cavendish Lab footsteps of J.J. Thomson. Rutherford died in 1937, having led a first wave of discovery of the atom. -

Charles Darwin: a Companion

CHARLES DARWIN: A COMPANION Charles Darwin aged 59. Reproduction of a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron, original 13 x 10 inches, taken at Dumbola Lodge, Freshwater, Isle of Wight in July 1869. The original print is signed and authenticated by Mrs Cameron and also signed by Darwin. It bears Colnaghi's blind embossed registration. [page 3] CHARLES DARWIN A Companion by R. B. FREEMAN Department of Zoology University College London DAWSON [page 4] First published in 1978 © R. B. Freeman 1978 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher: Wm Dawson & Sons Ltd, Cannon House Folkestone, Kent, England Archon Books, The Shoe String Press, Inc 995 Sherman Avenue, Hamden, Connecticut 06514 USA British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Freeman, Richard Broke. Charles Darwin. 1. Darwin, Charles – Dictionaries, indexes, etc. 575′. 0092′4 QH31. D2 ISBN 0–7129–0901–X Archon ISBN 0–208–01739–9 LC 78–40928 Filmset in 11/12 pt Bembo Printed and bound in Great Britain by W & J Mackay Limited, Chatham [page 5] CONTENTS List of Illustrations 6 Introduction 7 Acknowledgements 10 Abbreviations 11 Text 17–309 [page 6] LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Charles Darwin aged 59 Frontispiece From a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron Skeleton Pedigree of Charles Robert Darwin 66 Pedigree to show Charles Robert Darwin's Relationship to his Wife Emma 67 Wedgwood Pedigree of Robert Darwin's Children and Grandchildren 68 Arms and Crest of Robert Waring Darwin 69 Research Notes on Insectivorous Plants 1860 90 Charles Darwin's Full Signature 91 [page 7] INTRODUCTION THIS Companion is about Charles Darwin the man: it is not about evolution by natural selection, nor is it about any other of his theoretical or experimental work. -

Philosophical Rhetoric in Early Quantum Mechanics, 1925-1927

b1043_Chapter-2.4.qxd 1/27/2011 7:30 PM Page 319 b1043 Quantum Mechanics and Weimar Culture FA 319 Philosophical Rhetoric in Early Quantum Mechanics 1925–27: High Principles, Cultural Values and Professional Anxieties Alexei Kojevnikov* ‘I look on most general reasoning in science as [an] opportunistic (success- or unsuccessful) relationship between conceptions more or less defined by other conception[s] and helping us to overlook [danicism for “survey”] things.’ Niels Bohr (1919)1 This paper considers the role played by philosophical conceptions in the process of the development of quantum mechanics, 1925–1927, and analyses stances taken by key participants on four main issues of the controversy (Anschaulichkeit, quantum discontinuity, the wave-particle dilemma and causality). Social and cultural values and anxieties at the time of general crisis, as identified by Paul Forman, strongly affected the language of the debate. At the same time, individual philosophical positions presented as strongly-held principles were in fact flexible and sometimes reversible to almost their opposites. One can understand the dynamics of rhetorical shifts and changing strategies, if one considers interpretational debates as a way * Department of History, University of British Columbia, 1873 East Mall, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada V6T 1Z1; [email protected]. The following abbreviations are used: AHQP, Archive for History of Quantum Physics, NBA, Copenhagen; AP, Annalen der Physik; HSPS, Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences; NBA, Niels Bohr Archive, Niels Bohr Institute, Copenhagen; NW, Die Naturwissenschaften; PWB, Wolfgang Pauli, Wissenschaftlicher Briefwechsel mit Bohr, Einstein, Heisenberg a.o., Band I: 1919–1929, ed. A. Hermann, K.V. -

Revisiting One World Or None

Revisiting One World or None. Sixty years ago, atomic energy was new and the world was still reverberating from the shocks of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Immediately after the end of the Second World War, the first instinct of the administration and Congress was to protect the “secret” of the atomic bomb. The atomic scientists—what today would be called nuclear physicists— who had worked on the Manhattan project to develop atomic bombs recognized that there was no secret, that any technically advanced nation could, with adequate resources, reproduce what they had done. They further believed that when a single aircraft, eventually a single missile, armed with a single bomb could destroy an entire city, no defense system would ever be adequate. Given this combination, the world seemed headed for a period of unprecedented danger. Many of the scientists who had worked on the Manhattan Project felt a special responsibility to encourage a public debate about these new and terrifying products of modern science. They formed an organization, the Federation of Atomic Scientists, dedicated to avoiding the threat of nuclear weapons and nuclear proliferation. Convinced that neither guarding the nuclear “secret” nor any defense could keep the world safe, they encouraged international openness in nuclear physics research and in the expected nuclear power industry as the only way to avoid a disastrous arms race in nuclear weapons. William Higinbotham, the first Chairman of the Association of Los Alamos Scientists and the first Chairman of the Federation of Atomic Scientists, wanted to expand the organization beyond those who had worked on the Manhattan Project, for two reasons. -

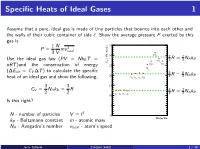

Einstein Solid 1 / 36 the Results 2

Specific Heats of Ideal Gases 1 Assume that a pure, ideal gas is made of tiny particles that bounce into each other and the walls of their cubic container of side `. Show the average pressure P exerted by this gas is 1 N 35 P = mv 2 3 V total SO 30 2 7 7 (J/K-mole) R = NAkB Use the ideal gas law (PV = NkB T = V 2 2 CO2 C H O CH nRT )and the conservation of energy 25 2 4 Cl2 (∆Eint = CV ∆T ) to calculate the specific 5 5 20 2 R = 2 NAkB heat of an ideal gas and show the following. H2 N2 O2 CO 3 3 15 CV = NAkB = R 3 3 R = NAkB 2 2 He Ar Ne Kr 2 2 10 Is this right? 5 3 N - number of particles V = ` 0 Molecule kB - Boltzmann constant m - atomic mass NA - Avogadro's number vtotal - atom's speed Jerry Gilfoyle Einstein Solid 1 / 36 The Results 2 1 N 2 2 N 7 P = mv = hEkini 2 NAkB 3 V total 3 V 35 30 SO2 3 (J/K-mole) V 5 CO2 C N k hEkini = NkB T H O CH 2 A B 2 25 2 4 Cl2 20 H N O CO 3 3 2 2 2 3 CV = NAkB = R 2 NAkB 2 2 15 He Ar Ne Kr 10 5 0 Molecule Jerry Gilfoyle Einstein Solid 2 / 36 Quantum mechanically 2 E qm = `(` + 1) ~ rot 2I where l is the angular momen- tum quantum number. -

Darwin in the Press: What the Spanish Dailies Said About the 200Th Anniversary of Charles Darwin’S Birth

CONTRIBUTIONS to SCIENCE, 5 (2): 193–198 (2009) Institut d’Estudis Catalans, Barcelona Celebration of the Darwin Year 2009 DOI: 10.2436/20.7010.01.75 ISSN: 1575-6343 www.cat-science.cat Darwin in the press: What the Spanish dailies said about the 200th anniversary of Charles Darwin’s birth Esther Díez, Anna Mateu, Martí Domínguez Mètode, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain Resum. El bicentenari del naixement de Charles Darwin, cele- Summary. The bicentenary of Charles Darwin’s birth, cele- brat durant el passat any 2009, va provocar un considerable brated in 2009, caused a surge in the interest shown by the augment de l’interés informatiu de la figura del naturalista an- press in the life and work of the renowned English naturalist. glès. En aquest article s’analitza la cobertura informativa This article analyzes the press coverage devoted to the Darwin d’aquest aniversari en onze diaris generalistes espanyols, i Year in eleven Spanish daily papers during the week of Dar- s’estableix grosso modo quines són les principals postures de win’s birthday and provides a brief synopsis of the positions la premsa espanyola davant de la teoria de l’evolució. D’aques- adopted by the Spanish press regarding the theory of evolu- ta anàlisi, queda ben palès com el creacionisme és encara molt tion. The analysis makes very clear the relatively strong support viu en els mitjans espanyols més conservadors. for creationism by the conservative press in Spain. Paraules clau: Charles Darwin ∙ ciència vs. creacionisme ∙ Keywords: Charles Darwin ∙ science vs. creationism ∙ tractament informatiu científic scientific news coverage “The more we know of the fixed laws of nature the more In this article, we examine to what extent and in what form incredible do miracles become.” this controversy persists in Spanish society, focusing on the print media’s response to the celebration, in 2009, of the 200th Charles Darwin (1887). -

Otto Sackur's Pioneering Exploits in the Quantum Theory Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Catalogo dei prodotti della ricerca Chapter 3 Putting the Quantum to Work: Otto Sackur’s Pioneering Exploits in the Quantum Theory of Gases Massimiliano Badino and Bretislav Friedrich After its appearance in the context of radiation theory, the quantum hypothesis rapidly diffused into other fields. By 1910, the crisis of classical traditions of physics and chemistry—while taking the quantum into account—became increas- ingly evident. The First Solvay Conference in 1911 pushed quantum theory to the fore, and many leading physicists responded by embracing the quantum hypoth- esis as a way to solve outstanding problems in the theory of matter. Until about 1910, quantum physics had drawn much of its inspiration from two sources. The first was the complex formal machinery connected with Max Planck’s theory of radiation and, above all, its close relationship with probabilis- tic arguments and statistical mechanics. The fledgling 1900–1901 version of this theory hinged on the application of Ludwig Boltzmann’s 1877 combinatorial pro- cedure to determine the state of maximum probability for a set of oscillators. In his 1906 book on heat radiation, Planck made the connection with gas theory even tighter. To illustrate the use of the procedure Boltzmann originally developed for an ideal gas, Planck showed how to extend the analysis of the phase space, com- monplace among practitioners of statistical mechanics, to electromagnetic oscil- lators (Planck 1906, 140–148). In doing so, Planck identified a crucial difference between the phase space of the gas molecules and that of oscillators used in quan- tum theory. -

![I. I. Rabi Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered Tue Apr](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8589/i-i-rabi-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-rendered-tue-apr-428589.webp)

I. I. Rabi Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered Tue Apr

I. I. Rabi Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 1992 Revised 2010 March Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms998009 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm89076467 Prepared by Joseph Sullivan with the assistance of Kathleen A. Kelly and John R. Monagle Collection Summary Title: I. I. Rabi Papers Span Dates: 1899-1989 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1945-1968) ID No.: MSS76467 Creator: Rabi, I. I. (Isador Isaac), 1898- Extent: 41,500 items ; 105 cartons plus 1 oversize plus 4 classified ; 42 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Physicist and educator. The collection documents Rabi's research in physics, particularly in the fields of radar and nuclear energy, leading to the development of lasers, atomic clocks, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and to his 1944 Nobel Prize in physics; his work as a consultant to the atomic bomb project at Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory and as an advisor on science policy to the United States government, the United Nations, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization during and after World War II; and his studies, research, and professorships in physics chiefly at Columbia University and also at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. -

Front Matter (PDF)

PROCEEDINGS OF THE OYAL SOCIETY OF LONDON Series A CONTAINING PAPERS OF A MATHEMATICAL AND PHYSICAL CHARACTER. VOL. LXXXV. LONDON: P rinted for THE ROYAL SOCIETY and S old by HARRISON AND SONS, ST. MARTIN’S LANE, PRINTERS IN ORDINARY TO HIS MAJESTY. N ovember, 1911. LONDON: HARRISON AND SONS, PRINTERS IN ORDINARY TO HTS MAJESTY, ST. MARTIN’S LANE. CONTENTS --- 0 0 ^ 0 0 ----- SERIES A. VOL. LXXXV. No. A 575.—March 14, 1911. P AG-E The Chemical Physics involved in the Precipitation of Free Carbon from the Alloys of the Iron-Carbon System. By W. H. Hatfield, B. Met. (Sheffield University). Communicated by Prof. W. M. Hicks, F.R.S. (Plates 1—5) ................... .......... 1 On the Fourier Constants of a Function. By W. H. Young, Se.D., F.R.S................. 14 The Charges on Ions in Gases, and some Effects that Influence the Motion of Negative Ions. By Prof. John S. Townsend, F.R.S............................................... 25 On the Energy and Distribution of Scattered Rontgen Radiation. By J. A. Crowtlier, M.A., Fellow of St. John's College, Cambridge. Com municated by Prof. Sir J. J. Thomson, F.R.S...........................*.............................. 29 The Origin of Magnetic Storms. By Arthur Schuster, F.R.S...................................... 44 On the Periodicity of Sun-spots. By Arthur Schuster, F.R.S..................................... 50 The Absorption Spectx*a of Lithium and Caesium. By Prof. P. V. Bevan, M.A., Royal Holloway College. Communicated by Sir J. J. Thomson, F.R.S.............. 54 Dispersion in Vapours of the Alkali Metals. By Prof. P. V. Bevan, M.A., Royal Holloway College. -

The XMM-Newton SAS - Distributed Development and Maintenance of a Large Science Analysis System: a Critical Analysis

Astronomical Data Analysis Software and Systems XIII ASP Conference Series, Vol. 314, 2004 F. Ochsenbein, M. Allen, and D. Egret, eds. The XMM-Newton SAS - Distributed Development and Maintenance of a Large Science Analysis System: A Critical Analysis Carlos Gabriel1, John Hoar1, Aitor Ibarra1, Uwe Lammers2, Eduardo Ojero1, Richard Saxton1, Giuseppe Vacanti2 XMM-Newton Science Operations Centre, Science Operations and Data Systems Division of ESA, European Space Agency Mike Denby, Duncan Fyfe, Julian Osborne Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Leicester, Leicester, LE1 7RH, UK Abstract. The XMM-Newton Scientific Analysis System (SAS) is the software used for the reduction and calibration of data taken with the XMM-Newton satellite instruments leading to almost 400 refereed scien- tific papers published in the last 2.5 years. Its maintenance, further devel- opment and distribution is under the responsibility of the XMM-Newton Science Operations Centre together with the Survey Science Centre, rep- resenting a collaborative effort of more than 30 scientific institutes. Developed in C++, Fortran 90/95 and Perl, the SAS makes large use of open software packages such as ds9 for image display (SAO-R&D Software Suite), Grace, LHEASOFT and cfitsio (HEASARC project), pgplot, fftw and the non-commercial version of Qt (TrollTech). The combination of supporting several versions of SAS for multiple platforms (including SunOS, DEC, many Linux flavours and MacOS) in a widely distributed development process which makes use of a suite of ex- ternal packages and libraries presents substantial issues for the integrity of the SAS maintenance and development. A further challenge comes from the necessity of maintaining the flexibility of a software package evolving together with progress made in instrument calibration and anal- ysis refinement, whilst at the same time being the source of all official products of the XMM-Newton mission.