Download This Article (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helium Mrs. Ahng the Second Lightest Element on Earth, Helium Is One Of

Helium Mrs. Ahng The second lightest element on Earth, Helium is one of the most important elements in our universe. It is the reason that we have sunlight, it makes balloons float, and used to cool down nuclear reactors. Although it is a simple noble gas with only two protons and two electrons, it is a powerful and essential resource. Discovered in1868 by astronomer Pierre Janssen while studying a solar eclipse; he noticed a yellow line around sun that had a wavelength that he had not seen before. English Astronomer Sir Norman Lockyer later named the element after the Greek word “Helios”, making the connection to how it was discovered. Helium only makes ups less than 1% of Earth’s atmosphere because of how light it is. It’s atomic mass is only 4.003, so the surrounding air is heavier than helium. An example of the difference in mass can be seen when comparing a helium filled balloon to a balloon filled with a mixture of atmospheric gases. The mass of the mixture is much heavier, and therefore is more effected by gravitational pull. Helium is found mostly in space in the core of stars, but it was also found on Earth in 1895 trapped underground. Scientists believe that the Helium that we harvest today was created during the creation of the universe, or the “Big Bang”. Only two electrons energize one orbital for this element, giving us the popular image for all atoms. With the outer orbital shell full, the element is referred to as inert and nonreactive. -

![Arxiv:0906.0144V1 [Physics.Hist-Ph] 31 May 2009 Event](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2044/arxiv-0906-0144v1-physics-hist-ph-31-may-2009-event-142044.webp)

Arxiv:0906.0144V1 [Physics.Hist-Ph] 31 May 2009 Event

Solar physics at the Kodaikanal Observatory: A Historical Perspective S. S. Hasan, D.C.V. Mallik, S. P. Bagare & S. P. Rajaguru Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Bangalore, India 1 Background The Kodaikanal Observatory traces its origins to the East India Company which started an observatory in Madras \for promoting the knowledge of as- tronomy, geography and navigation in India". Observations began in 1787 at the initiative of William Petrie, an officer of the Company, with the use of two 3-in achromatic telescopes, two astronomical clocks with compound penduumns and a transit instrument. By the early 19th century the Madras Observatory had already established a reputation as a leading astronomical centre devoted to work on the fundamental positions of stars, and a principal source of stellar positions for most of the southern hemisphere stars. John Goldingham (1796 - 1805, 1812 - 1830), T. G. Taylor (1830 - 1848), W. S. Jacob (1849 - 1858) and Norman R. Pogson (1861 - 1891) were successive Government Astronomers who led the activities in Madras. Scientific high- lights of the work included a catalogue of 11,000 southern stars produced by the Madras Observatory in 1844 under Taylor's direction using the new 5-ft transit instrument. The observatory had recently acquired a transit circle by Troughton and Simms which was mounted and ready for use in 1862. Norman Pogson, a well known astronomer whose name is associated with the modern definition of the magnitude scale and who had considerable experience with transit instruments in England, put this instrument to good use. With the help of his Indian assistants, Pogson measured accurate positions of about 50,000 stars from 1861 until his death in 1891. -

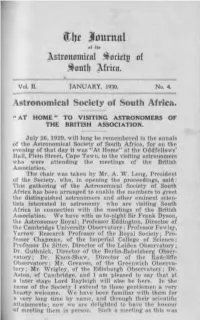

Assaj V2 N4 1930-Jan

ijtlJt Journal {If tl]t J\.strauamital ~ add!,! af ~ autb J\.frita. Vol. II. JANUARY, 1930. No.4. Astronomical Society of South Africa~ "' AT HOME" TO VISITING ASTRONOMERS OF THE BRITISH ASSOCIATION. July 26, 1929, will long be remembered in the annals of the Astronomical Society of South Africa, for on the evening of that day it was "At Home" at the Oddfellows' Hall, Plein Street, Cape Town, to the visiting astronomers who were attending the meetings of the British Association. The chair was taken by Mr. A. W. Long, President of the Society, who, in opening the proceedings, said: This gathering of the Astronomical Society of South Africa has been arranged to enable the members to greet the distinguished astronomers and other eminent scien tists interested in astronomy who are visiting South Africa in connection with the meetings of the British Association. We have with us to-night Sir Frank Dyson, the Astronomer Royal; Professor Eddington, Director of the Cambridge University Observatory; Professor Fowl~r, Yarrow Research Professor of the Royal Society; Pro fessor Chapman, of the Imperial College of Science; Professor De Sitter, Director of the Leiden Observatory; Dr. Guthnick, Director of the Berlin-Babelsberg Obser vatory; Dr. K110x-Shaw, Director of the Radcliffe Observatory; Mr. Greaves, of the Greenwich Observa tory; Mr. Wrigley, of the Edinburgh Observatory; Dr. Aston, of Cambridge, and I am pleased to say that at a later stage Lord Rayleigh will also be here. In the name of the Society I extend to these gentlemen a very hearty welcome. We have been familiar with them for a very long time by name, and through their scientific attainments; now we are delighted to have the honour of meeting them in person. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers Past Masters Since 1631

The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers Past Masters since 1631 1631 David Ramsey (named in the Charter) 1700 Charles Gretton 1800 Matthew Dutton 1632 David Ramsey (sworn 22nd October) 1701 William Speakman 1801 William Plumley 1633 David Ramsey, represented by his Deputy, Henry Archer 1702 Joseph Windmills 1802 Edward Gibson 1634 Sampson Shelton 1703 Thomas Tompion 1803 Timothy Chisman 1635 John Willow 1704 Robert Webster 1804 William Pearce 1636 Elias Allen 1705 Benjamin Graves 1805 William Robins 1638 John Smith 1706 John Finch 1806 Francis S Perigal Jnr 1639 Sampson Shelton 1707 John Pepys 1807 Samuel Taylor 1640 John Charleton 1708 Daniel Quare 1808 Thomas Dolley 1641 John Harris 1709 George Etherington 1809 William Robson 1642 Richard Masterson 1710 Thomas Taylor 1810 Paul Philip Barraud 1643 John Harris 1711 Thomas Gibbs 1811 Paul Philip Barraud 1644 John Harris 1712 John Shaw 1812 Harry Potter (died) 1645 Edward East 1713 Sir George Mettins (Lord Mayor 1724–1725) 1813 Isaac Rogers 1646 Simon Hackett 1714 John Barrow 1814 William Robins 1647 Simon Hackett 1715 Thomas Feilder 1815 John Thwaites 1648 Robert Grinkin 1716 William Jaques 1816 William Robson 1649 Robert Grinkin 1717 Nathaniel Chamberlain 1817 John Roger Arnold 1650 Simon Bartram 1718 Thomas Windmills 1818 William Robson 1651 Simon Bartram 1719 Edward Crouch 1819 John Thwaites 1652 Edward East 1720 James Markwick 1820 John Thwaites 1653 John Nicasius 1721 Martin Jackson 1821 Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy 1654 Robert Grinkin 1722 George Graham 1822 John Jackson Jnr 1655 John Nicasius -

Einstein, Eddington, and the Eclipse: Travel Impressions

EINSTEIN, EDDINGTON, AND THE ECLIPSE: TRAVEL IMPRESSIONS ESSAY 195 INTRODUCTION The total solar eclipse that occurred on 29 May 1919—perhaps considered the most famous solar eclipse ever—was exceptional for a variety of scientific, political, social, and even religious reasons. At just over five minutes of totality (more precisely, 302 seconds), it was a long eclipse. Behind the sun appeared the Taurus constellation, which included the Hyades, the brightest star cluster in the ecliptic. The preparations of the British teams that observed it, and which are the subject of this essay, took place in the middle of the Great War, during a period of international instability. The observation locations selected by these specialists were in the tropics, in distant regions unknown to most astronomers, and thus required extensive preparations. These places included the city of Sobral, in the north-eastern state of Ceará in Brazil, and the equatorial island of Príncipe, then part of the Portuguese empire, and today part of the Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe. Located in the Gulf of Guinea on the West African coast, Príncipe was then known as one of the world’s largest cocoa producers, and was under international suspicion for practicing slave labour. Additionally, among the teams of expeditionary astronomers from various countries—including the United Kingdom, the United States, and Brazil—there was not just one, but two British teams. This was an uncommon choice given the material, as well as the scientific and financial effort involved, accentuated by the unfavourable context of the war. The expedition that observed at Príncipe included Arthur Stanley Eddington (1882– 1944), the astrophysicist and young director of the Cambridge Observatory, as well as the clockmaker and calculator Edwin Turner Cottingham (1869–1940); the expedition that visited Brazil included Andrew Claude de la Cherois Crommelin (1865–1939), and Charles Rundle Davidson (1875–1970), both experienced astronomers at the Greenwich Observatory (see pp. -

Norman Lockyer Resources Information Sheet

Norman Lockyer resources information sheet Sir Joseph Lockyer was born in Rugby in 1836, the only son of a surgeon-apothecary, Joseph Hooley Lockyer and was educated privately in England and he also studied languages on the Continent. At the age of twenty-one he became a clerk in the War Office, and married Winifred James in the following year. He developed an interest in astronomy and journalism, and in 1863 began to give scientific papers to the Royal Astronomical Society. It is his discovery of helium which he has become most well known for. In 1869 Lockyer founded the journal 'Nature', which he edited until a few months before his death, and which remains to this day a major resource for international scientific knowledge. In 1870 he was appointed secretary to the Royal Commission on Scientific Instruction, which over the next five years reported on scientific education and resulted in the government setting up a laboratory of solar physics at South Kensington. To further this work Lockyer was transferred from the War Office to the Science and Art Department at South Kensington in 1875. Here he organised an international exhibition of scientific apparatus, as well as establishing the loan collection which eventually formed the nucleus of the collections of the Science Museum. Throughout this period, Lockyer continued to be active in astronomical observations and in spectroscopic studies in the laboratory of the College of Chemistry; he also wrote several books on astronomy and spectral analysis. Lockyer also studied the correlations between solar activity and weather, and developed interests in meteorology. -

How the Saha Ionization Equation Was Discovered

How the Saha Ionization Equation Was Discovered Arnab Rai Choudhuri Department of Physics, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore – 560012 Introduction Most youngsters aspiring for a career in physics research would be learning the basic research tools under the guidance of a supervisor at the age of 26. It was at this tender age of 26 that Meghnad Saha, who was working at Calcutta University far away from the world’s major centres of physics research and who never had a formal training from any research supervisor, formulated the celebrated Saha ionization equation and revolutionized astrophysics by applying it to solve some long-standing astrophysical problems. The Saha ionization equation is a standard topic in statistical mechanics and is covered in many well-known textbooks of thermodynamics and statistical mechanics [1–3]. Professional physicists are expected to be familiar with it and to know how it can be derived from the fundamental principles of statistical mechanics. But most professional physicists probably would not know the exact nature of Saha’s contributions in the field. Was he the first person who derived and arrived at this equation? It may come as a surprise to many to know that Saha did not derive the equation named after him! He was not even the first person to write down this equation! The equation now called the Saha ionization equation appeared in at least two papers (by J. Eggert [4] and by F.A. Lindemann [5]) published before the first paper by Saha on this subject. The story of how the theory of thermal ionization came into being is full of many dramatic twists and turns. -

One of the Most Celebrated Physics Experiments of the 20Th Cent

Not Only Because of Theory: Dyson, Eddington and the Competing Myths of the 1919 Eclipse Expedition Introduction One of the most celebrated physics experiments of the 20th century, a century of many great breakthroughs in physics, took place on May 29th, 1919 in two remote equatorial locations. One was the town of Sobral in northern Brazil, the other the island of Principe off the west coast of Africa. The experiment in question concerned the problem of whether light rays are deflected by gravitational forces, and took the form of astrometric observations of the positions of stars near the Sun during a total solar eclipse. The expedition to observe the eclipse proved to be one of those infrequent, but recurring, moments when astronomical observations have overthrown the foundations of physics. In this case it helped replace Newton’s Law of Gravity with Einstein’s theory of General Relativity as the generally accepted fundamental theory of gravity. It also became, almost immediately, one of those uncommon occasions when a scientific endeavor captures and holds the attention of the public throughout the world. In recent decades, however, questions have been raised about possible bias and poor judgment in the analysis of the data taken on that famous day. It has been alleged that the best known astronomer involved in the expedition, Arthur Stanley Eddington, was so sure beforehand that the results would vindicate Einstein’s theory that, for unjustifiable reasons, he threw out some of the data which did not agree with his preconceptions. This story, that there was something scientifically fishy about one of the most famous examples of an experimentum crucis in the history of science, has now become well known, both amongst scientists and laypeople interested in science. -

Book Reviews Biman Nath, the Story of Helium and the Birth of Astrophysics

Phys. Perspect. 15 (2013) 361–370 Ó 2013 Springer Basel 1422-6944/13/030361-10 DOI 10.1007/s00016-013-0121-5 Physics in Perspective Book Reviews Biman Nath, The Story of Helium and the Birth of Astrophysics. Heidelberg: Springer, 2012, 285 pages. $39.95 (cloth). Helium is the only chemical element ever to be first found anyplace except on earth, despite transitory claims for nebulium, coronium, aldebarium, asterium, cassiopeum, and more. Because the periodic table is now filled at least as far as Z = 112 (Copernicium, with a very short half-life) this will remain true at least as long as the only chemists and physicists we know are confined to terrestrial labs. Biman Nath’s history of the discovery of helium involves astronomy, chemistry, and physics, and so is particularly appropriate for 2013, which is the centenary both of the Bohr atom and of the first of two short papers by Henry Moseley (1887–1915) that established the primacy of Z (atomic number) over A (atomic weight) for constructing periodic tables and, in due course, for understanding the synthesis of the elements in stars. The crucial observations in the helium story were made from Guntur and Masulipam, India, during a long total solar eclipse in August 1868 by expeditions under the leadership of Jules Janssen (for France) and James Tennant and Norman Pogson (for England). John Herschel, son of the one most astronomers know, Captain Haig, and Professor Kero Laxuman also observed from other sites in India, and George Rayet (fresh from his 1867 triumph in codiscovering stars with emission-line spectra) from the Malay Peninsula. -

Hubble Sees Light Bending Around Nearby Star : Nature News

NATURE | NEWS Hubble sees light bending around nearby star Rare astronomical observation shows effects of relativity. Alexandra Witze 07 June 2017 STSI Stein 2051 B is a white-dwarf star in the constellation Camelopardalis. The Hubble Space Telescope has spotted light bending because of the gravity of a nearby white dwarf star — the first time astronomers have seen this type of distortion around a star other than the Sun. The finding once again confirms Einstein’s general theory of relativity. A team led by Kailash Sahu, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, watched the position of a distant star jiggle slightly, as its light bent around a white dwarf in the line of sight of observers on Earth. The amount of distortion allowed the researchers to directly calculate the white dwarf’s mass — 67% that of the Sun. “It’s a very difficult observation with a really nice result,” says Pier-Emmanuel Tremblay, an astrophysicist at the University of Warwick in Coventry, UK, who was not involved in the discovery. The findings were published in Science 1 and presented at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Austin, Texas, on 7 June. White dwarfs are the remains of stars that have finished burning their nuclear fuel. The Sun will eventually become one. Sahu’s team studied a white dwarf known as Stein 2051 B, in the constellation Camelopardalis. At 5 parsecs (17 light years) from Earth, it is the sixth-nearest white dwarf. Because it is so close, it appears to move quickly across the sky compared with more-distant stars. -

Smart Optics for ESA Space Science Missions

Smart Optics for ESA Space Science Missions • Gaia, JWST, Darwin • Scientific objectives • Payload description • Optical technology developments Dr. Ph. Gondoin (ESA) ESA’s IR and visible astronomy missions DARWIN GAIA Herschel Planck Eddington JWST 1 GAIA Science Objectives Understanding the structure and evolution of the Galaxy, i.e.: – census of the content of a large part of the Galaxy – quantification of the present spatial structure from distance (3-D map) – knowledge of the 3-D space motions Æ Complementary astrometry, photometry and radial velocities: – Astrometry: distance and tranverse kinematics – Photometry: extinction, intrinsic luminosity, abundances, ages, – Radial velocities: 3-D kinematics, gravitational forces, mass distribution, stellar orbits GAIA (compared with Hipparcos) Hipparcos GAIA Magnitude limit 12 20-21 mag Completeness 7.3 – 9.0 ~20 mag Bright limit ~0 ~3-7 mag Number of objects 120 000 26 million to V = 15 250 million to V = 18 1000 million to V = 20 Effective distance limit 1 kpc 1 Mpc Quasars None ~5 ×105 Galaxies None 106 - 107 Accuracy ~1 milliarcsec 4 µarcsec at V = 10 10 µarcsec at V = 15 200 µarcsec at V = 20 Broad band 2-colour (B and V) 4-colour to V = 20 Mediumphotometry band None 11-colour to V = 20 Radialphotometry velocity None 1-10 km/s to V = 16-17 Observing programme Pre-selected On-board and unbiased 2 PayloadGAIA payload • 2 astrometric telescopes: • Separated by 106o • SiC mirrors (1.4 m × 0.5 m) • Large focal plane (TDI operating CCDs) • 1 additional telescope equipped with: • Medium-band photometer • Radial-velocity spectrometer Optical technology for GAIA • CCD’s and focal plane technology: (ASTRIUM.GB+E2V under ESA TRP contract) – Astrometry: 3 side buttable, small pixel (9 µm), high perf.