November 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What the Renaissance Knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018

What the Renaissance knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 http://www.scaruffi.com/know 1 What the Renaissance knew • The 17th Century – For tens of thousands of years, humans had the same view of the universe and of the Earth. – Then the 17th century dramatically changed the history of humankind by changing the way we look at the universe and ourselves. – This happened in a Europe that was apparently imploding politically and militarily, amid massive, pervasive and endless warfare – Grayling refers to "the flowering of genius“: Galileo, Pascal, Kepler, Newton, Cervantes, Shakespeare, Donne, Milton, Racine, Moliere, Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Locke, Rubens, El Greco, Rembrandt, Vermeer… – Knowledge spread, ideas circulated more freely than people could travel 2 What the Renaissance knew • Collapse of classical dogmas – Aristotelian logic vs Rene Descartes' "Discourse on the Method" (1637) – Galean medicine vs Vesalius' anatomy (1543), Harvey's blood circulation (1628), and Rene Descartes' "Treatise of Man" (1632) – Ptolemaic cosmology vs Copernicus (1530) and Galileo (1632) – Aquinas' synthesis of Aristotle and the Bible vs Thomas Hobbes' synthesis of mechanics (1651) and Pierre Gassendi's synthesis of Epicurean atomism and anatomy (1655) – Papal unity: the Thirty Years War (1618-48) shows endless conflict within Christiandom 3 What the Renaissance knew • Decline of – Feudalism – Chivalry – Holy Roman Empire – Papal Monarchy – City-state – Guilds – Scholastic philosophy – Collectivism (Church, guild, commune) – Gothic architecture 4 What -

Ocabulary of Definitions : P

Service bibliothèque Catalogue historique de la bibliothèque de l’Observatoire de Nice Source : Monographie de l’Observatoire de Nice / Charles Garnier, 1892. Marc Heller © Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur Février 2012 Présentation << On trouve… à l’Ouest … la bibliothèque avec ses six mille deux cents volumes et ses trentes journaux ou recueils périodiques…. >> (Façade principale de la Bibliothèque / Phot. attribuée à Michaud A. – 188? - Marc Heller © Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur) C’est en ces termes qu’Henri Joseph Anastase Perrotin décrivait la bibliothèque de l’Observatoire de Nice en 1899 dans l’introduction du tome 1 des Annales de l’Observatoire de Nice 1. Un catalogue des revues et ouvrages 2 classé par ordre alphabétique d’auteurs et de lieux décrivait le fonds historique de la bibliothèque. 1 Introduction, Annales de l’Observatoire de Nice publiés sous les auspices du Bureau des longitudes par M. Perrotin. Paris,Gauthier-Villars,1899, Tome 1,p. XIV 2 Catalogue de la bibliothèque, Annales de l’Observatoire de Nice publiés sous les auspices du Bureau des longitudes par M. Perrotin. Paris,Gauthier-Villars,1899, Tome 1,p. 1 Le présent document est une version remaniée, complétée et enrichie de ce catalogue. (Bibliothèque, vue de l’intérieur par le photogr. Jean Giletta, 191?. - Marc Heller © Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur) Chaque référence est reproduite à l’identique. Elle est complétée par une notice bibliographique et éventuellement par un lien électronique sur la version numérisée. Les titres et documents non encore identifiés sont signalés en italique. Un index des auteurs et des titres de revues termine le document. -

Dr. Julie Brown, CTO of UDC, Awarded Prestigious 2020 Karl Ferdinand Braun Prize from the Society of Information Display

8/3/2020 Dr. Julie Brown, CTO of UDC, Awarded Prestigious 2020 Karl Ferdinand Braun Prize from the Society of Information Display Dr. Mike Weaver, VP of UDC, Honored with 2020 SID Fellow Award EWING, N.J.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Universal Display Corporation (Nasdaq: OLED), enabling energy-efficient displays and lighting with its UniversalPHOLED® technology and materials, today announced that Dr. Julie Brown, Senior Vice President and Chief Technical Officer, was awarded the 2020 Karl Ferdinand Braun Prize by the Society of Information Display (SID). Additionally, Dr. Mike Weaver, Vice President of PHOLED R&D, was named a 2020 SID Fellow. The Karl Ferdinand Braun Prize was awarded to Dr. Brown for her outstanding technical achievements and contributions to the development and commercialization of phosphorescent OLED materials and display technology. The Society for Information Display created this prize in 1987 in honor of the German physicist and Nobel Laureate Karl Ferdinand Braun who invented the cathode-ray tube (CRT). Dr. Brown has been a leading innovator in the discovery and development of state-of-the-art OLED technologies and materials for display and lighting applications for over two decades, and is the first woman to be awarded this prestigious prize. Joining Universal Display (UDC) in 1998, Dr. Brown leads a global team of unique chemists, physicists and engineers and spearheads the R&D vision of UDC, from its start-up years to its successful commercial present, and continues to create and shape the Company’s innovation strategy for its future growth. The distinction of Fellow honors an SID member of outstanding qualifications and experience as a scientist or engineer in the field of information display. -

Great Physicists

Great Physicists Great Physicists The Life and Times of Leading Physicists from Galileo to Hawking William H. Cropper 1 2001 1 Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogota´ Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence HongKong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris Sao Paulo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright ᭧ 2001 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cropper, William H. Great Physicists: the life and times of leadingphysicists from Galileo to Hawking/ William H. Cropper. p. cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–19–513748–5 1. Physicists—Biography. I. Title. QC15 .C76 2001 530'.092'2—dc21 [B] 2001021611 987654321 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Contents Preface ix Acknowledgments xi I. Mechanics Historical Synopsis 3 1. How the Heavens Go 5 Galileo Galilei 2. A Man Obsessed 18 Isaac Newton II. Thermodynamics Historical Synopsis 41 3. A Tale of Two Revolutions 43 Sadi Carnot 4. On the Dark Side 51 Robert Mayer 5. A Holy Undertaking59 James Joule 6. Unities and a Unifier 71 Hermann Helmholtz 7. The Scientist as Virtuoso 78 William Thomson 8. -

Insights Into Abdominal Pregnancy Gwinyai Masukume

WikiJournal of Medicine, 2014, 1 (2) doi: 10.15347/wjm/2014.012 Review Article Insights into abdominal pregnancy Gwinyai Masukume Editor’s note This article provided a great deal of valuable evidence that was not mentioned in the Wikipedia article on ab- dominal pregnancy, and the Wikipedia article has subsequently been expanded with text from this publication. However, because of this purpose, it has never been the aim of this article in itself to be a complete review of the subject, and many aspects of abdominal pregnancy are not included herein. This article also provides an example of how to contribute to Wikimedia projects such as Wikipedia by means of academic publishing. Introduction Risk factors While rare, abdominal pregnancies have a higher Risk factors are similar to tubal pregnancy with sexually chance of maternal mortality, perinatal mortality and transmitted disease playing a major role.[7] However, morbidity compared to normal and ectopic pregnan- about half of those with ectopic pregnancy have no cies, but on occasion a healthy viable infant can be de- known risk factors - known risk factors include damage livered.[1] to the Fallopian tubes from previous surgery or from previous ectopic pregnancy and tobacco smoking.[8] Because tubal, ovarian and broad ligament pregnancies are as difficult to diagnose and treat as abdominal preg- nancies, their exclusion from the most common defini- tion of abdominal pregnancy has been debated.[2] Mechanism Others - in the minority - are of the view that abdominal Typically an abdominal -

Von Richthofen, Einstein and the AGA Estimating Achievement from Fame

Von Richthofen, Einstein and the AGA Estimating achievement from fame Every schoolboy has heard of Einstein; fewer have heard of Antoine Becquerel; almost nobody has heard of Nils Dalén. Yet they all won Nobel Prizes for Physics. Can we gauge a scientist’s achievements by his or her fame? If so, how? And how do fighter pilots help? Mikhail Simkin and Vwani Roychowdhury look for the linkages. “It was a famous victory.” We instinctively rank the had published. However, in 2001–2002 popular French achievements of great men and women by how famous TV presenters Igor and Grichka Bogdanoff published they are. But is instinct enough? And how exactly does a great man’s fame relate to the greatness of his achieve- ment? Some achievements are easy to quantify. Such is the case with fighter pilots of the First World War. Their achievements can be easily measured and ranked, in terms of their victories – the number of enemy planes they shot down. These aces achieved varying degrees of fame, which have lasted down to the internet age. A few years ago we compared1 the fame of First World War fighter pilot aces (measured in Google hits) with their achievement (measured in victories); and we found that We can estimate fame grows exponentially with achievement. fame from Google; Is the same true in other areas of excellence? Bagrow et al. have studied the relationship between can this tell us 2 achievement and fame for physicists . The relationship Manfred von Richthofen (in cockpit) with members of his so- about actual they found was linear. -

Issue N°2: Modeling Nothingness

t a m i n g _ t h e h o r r o r vacui issue #2 modeling nothingness March 2020. Reeds from the River Rupel in a potential state before being set in motion at Rib. IN ABSENCE OF SPIRIT by Christiane Blattmann Do houses have a soul that dwells within? A place has a spirit – Why should a habitation, then, not have a soul? Can buildings contain evil? When I studied architecture for a brief period of time, I had a professor who was obsessed with Heidegger. Her lectures were poetic and heavy, and we had to spend hours looking at slides of her watercolors in which she tried to capture the spirit of places she would travel to on weekends. The genius loci of a site – she explained. Der Ort. She always said DER ORT in a religious way that I found puzzling – the me of first semester, who had never read a line of Heidegger (and still don’t get much of it). Whenever she said DER ORT, I felt strangely ashamed, for I couldn’t decipher the charge of her expression. I had a feeling that I didn’t share in her religion. What I could explain better to myself was the much older understanding my professor was referring to. The genii in ancient belief were protective spirits that guarded a place or a house. They would make the difference between a place and DER ORT: between an anonymous area on the map, a mere fenced-off field and a textured site, with history, character, a view, underground, traps, and inexplicable vibes to it. -

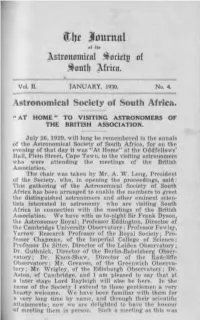

Assaj V2 N4 1930-Jan

ijtlJt Journal {If tl]t J\.strauamital ~ add!,! af ~ autb J\.frita. Vol. II. JANUARY, 1930. No.4. Astronomical Society of South Africa~ "' AT HOME" TO VISITING ASTRONOMERS OF THE BRITISH ASSOCIATION. July 26, 1929, will long be remembered in the annals of the Astronomical Society of South Africa, for on the evening of that day it was "At Home" at the Oddfellows' Hall, Plein Street, Cape Town, to the visiting astronomers who were attending the meetings of the British Association. The chair was taken by Mr. A. W. Long, President of the Society, who, in opening the proceedings, said: This gathering of the Astronomical Society of South Africa has been arranged to enable the members to greet the distinguished astronomers and other eminent scien tists interested in astronomy who are visiting South Africa in connection with the meetings of the British Association. We have with us to-night Sir Frank Dyson, the Astronomer Royal; Professor Eddington, Director of the Cambridge University Observatory; Professor Fowl~r, Yarrow Research Professor of the Royal Society; Pro fessor Chapman, of the Imperial College of Science; Professor De Sitter, Director of the Leiden Observatory; Dr. Guthnick, Director of the Berlin-Babelsberg Obser vatory; Dr. K110x-Shaw, Director of the Radcliffe Observatory; Mr. Greaves, of the Greenwich Observa tory; Mr. Wrigley, of the Edinburgh Observatory; Dr. Aston, of Cambridge, and I am pleased to say that at a later stage Lord Rayleigh will also be here. In the name of the Society I extend to these gentlemen a very hearty welcome. We have been familiar with them for a very long time by name, and through their scientific attainments; now we are delighted to have the honour of meeting them in person. -

Extra Uterine Pregnancy

University of Nebraska Medical Center DigitalCommons@UNMC MD Theses Special Collections 5-1-1933 Extra uterine pregnancy Jacob F. Schultz University of Nebraska Medical Center This manuscript is historical in nature and may not reflect current medical research and practice. Search PubMed for current research. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/mdtheses Recommended Citation Schultz, Jacob F., "Extra uterine pregnancy" (1933). MD Theses. 290. https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/mdtheses/290 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at DigitalCommons@UNMC. It has been accepted for inclusion in MD Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNMC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EX! R A - U ! E R I N E PRE G NAN C Y. JACOB F. SCHUL!Z. 480528 1 HISTORY Extra-ute ine pregn_cy was apparently Ul'lkna1'lll to the ancleJllts, theft- bei~ no reference to the su.b~ee't in the works on Greek or Roman meti eiDt. The f'ir st recorded case is that of' A1bucasis, an Arabian ph7s1cian living in Spain about the middle of' tbt eleventh century. He reports a ease whe re he saw parts of' a foetal body escaping from the abdomen of a woman by the process of suppurat ion. This was a case of a long retained secondary abdominal pregnaBcy, and all at the older eases that were reported were of - this type. Al'lother interesting example is that of the lithopedion of sens, Reported by Cordeaus early in the sixteenth century. -

Keeping the Promise: Phys Rev Completes Online Archive the Physical Review Be Explored

August/September 2001 NEWS Volume 10, No. 8 A Publication of The American Physical Society http://www.aps.org/apsnews Keeping the Promise: Phys Rev Completes Online Archive The Physical Review be explored. The earliest volumes institutions and others to link to Online Archive or of the journals can be examined at APS publications, both current ma- PRL Gets a PROLA is now com- length, in detail and at ease. Histo- terial and PROLA. Authors are also plete: every paper in rians and biographers can track the free to mount their Physical Review New Face every journal that APS expansion of the knowledge of papers on their own sites. has published since physics that took place over the PROLA is composed of scanned 1893 (excepting the previous century in Physical Review. images of the printed journals, op- present and past three Research published in Physical Re- tical character recognition (OCR) years, which are held view by any particular author or material, and a searchable separately for current group or institution can be col- richly-tagged XML bibliographic subscribers) mounted lected and perused with a search database. Each year, another year online in a friendly, of PROLA and a second search of of this material is added to PROLA Bob Kelly/APS powerful, fully search- PROLA team at APS Editorial Office in Ridge, NY: Louise current content. Journalists can ac- from the current subscription con- able system. The project Bogan; Paul Dlug; Mark Doyle, Project Manager; Maxim cess physics Nobel Prize winning tent; 1997 was added in January took just under ten Gregoriev; Gerard Young; Rosemary Clark. -

Curren T Anthropology

Forthcoming Current Anthropology Wenner-Gren Symposium Curren Supplementary Issues (in order of appearance) t Humanness and Potentiality: Revisiting the Anthropological Object in the Anthropolog Current Context of New Medical Technologies. Klaus Hoeyer and Karen-Sue Taussig, eds. Alternative Pathways to Complexity: Evolutionary Trajectories in the Anthropology Middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age. Steven L. Kuhn and Erella Hovers, eds. y THE WENNER-GREN SYMPOSIUM SERIES Previously Published Supplementary Issues December 2012 HUMAN BIOLOGY AND THE ORIGINS OF HOMO Working Memory: Beyond Language and Symbolism. omas Wynn and Frederick L. Coolidge, eds. GUEST EDITORS: SUSAN ANTÓN AND LESLIE C. AIELLO Engaged Anthropology: Diversity and Dilemmas. Setha M. Low and Sally Early Homo: Who, When, and Where Engle Merry, eds. Environmental and Behavioral Evidence V Dental Evidence for the Reconstruction of Diet in African Early Homo olum Corporate Lives: New Perspectives on the Social Life of the Corporate Form. Body Size, Body Shape, and the Circumscription of the Genus Homo Damani Partridge, Marina Welker, and Rebecca Hardin, eds. Ecological Energetics in Early Homo e 5 Effects of Mortality, Subsistence, and Ecology on Human Adult Height 3 e Origins of Agriculture: New Data, New Ideas. T. Douglas Price and Plasticity in Human Life History Strategy Ofer Bar-Yosef, eds. Conditions for Evolution of Small Adult Body Size in Southern Africa Supplement Growth, Development, and Life History throughout the Evolution of Homo e Biological Anthropology of Living Human Populations: World Body Size, Size Variation, and Sexual Size Dimorphism in Early Homo Histories, National Styles, and International Networks. Susan Lindee and Ricardo Ventura Santos, eds. -

The Place of Otherness and Indeterminacy in Aristotelian Science

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1997 The Place of Otherness and Indeterminacy in Aristotelian Science Joshua William Rayman Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Rayman, Joshua William, "The Place of Otherness and Indeterminacy in Aristotelian Science" (1997). Master's Theses. 4266. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/4266 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1997 Joshua William Rayman LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO THE PLACE OF OTHERNESS AND INDETERMINACY IN ARISTOTELIAN SCIENCE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY BY JOSHUA WILLIAM RAYMAN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY 1997 Copyright by Joshua William Rayman, 1997 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION For Allison, Graham, young William Henry, and Mom and Dad TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT........................................................................ v INTRODUCTION . 1 CHAPTER ONE--OTHERNESS AND INDETERMINACY . 4 CHAPTER TWO--POTENTIAL AND MATTER........................... 53 CHAPTER THREE--THE ACCIDENTAL..................................