Vulgaris Seu Universalis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Southern Denmark

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN DENMARK THE CHRISTIAN KINGDOM AS AN IMAGE OF THE HEAVENLY KINGDOM ACCORDING TO ST. BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY INSTITUTE OF HISTORY, CULTURE AND CIVILISATION CENTRE FOR MEDIEVAL STUDIES BY EMILIA ŻOCHOWSKA ODENSE FEBRUARY 2010 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In my work, I had the privilege to be guided by three distinguished scholars: Professor Jacek Salij in Warsaw, and Professors Tore Nyberg and Kurt Villads Jensen in Odense. It is a pleasure to admit that this study would never been completed without the generous instruction and guidance of my masters. Professor Salij introduced me to the world of ancient and medieval theology and taught me the rules of scholarly work. Finally, he encouraged me to search for a new research environment where I could develop my skills. I found this environment in Odense, where Professor Nyberg kindly accepted me as his student and shared his vast knowledge with me. Studying with Professor Nyberg has been a great intellectual adventure and a pleasure. Moreover, I never would have been able to work at the University of Southern Denmark if not for my main supervisor, Kurt Villads Jensen, who trusted me and decided to give me the opportunity to study under his kind tutorial, for which I am exceedingly grateful. The trust and inspiration I received from him encouraged me to work and in fact made this study possible. Karen Fogh Rasmussen, the secretary of the Centre of Medieval Studies, had been the good spirit behind my work. -

Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States

Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States Winthrop D. Jordan1 Edited by Paul Spickard2 Editor’s Note Winthrop Jordan was one of the most honored US historians of the second half of the twentieth century. His subjects were race, gender, sex, slavery, and religion, and he wrote almost exclusively about the early centuries of American history. One of his first published articles, “American Chiaroscuro: The Status and Definition of Mulattoes in the British Colonies” (1962), may be considered an intellectual forerunner of multiracial studies, as it described the high degree of social and sexual mixing that occurred in the early centuries between Africans and Europeans in what later became the United States, and hinted at the subtle racial positionings of mixed people in those years.3 Jordan’s first book, White over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550–1812, was published in 1968 at the height of the Civil Rights Movement era. The product of years of painstaking archival research, attentive to the nuances of the thousands of documents that are its sources, and written in sparkling prose, White over Black showed as no previous book had done the subtle psycho-social origins of the American racial caste system.4 It won the National Book Award, the Ralph Waldo Emerson Prize, the Bancroft Prize, the Parkman Prize, and other honors. It has never been out of print since, and it remains a staple of the graduate school curriculum for American historians and scholars of ethnic studies. In 2005, the eminent public intellectual Gerald Early, at the request of the African American magazine American Legacy, listed what he believed to be the ten most influential books on African American history. -

The Status of the Least Documented Language Families in the World

Vol. 4 (2010), pp. 177-212 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4478 The status of the least documented language families in the world Harald Hammarström Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen and Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig This paper aims to list all known language families that are not yet extinct and all of whose member languages are very poorly documented, i.e., less than a sketch grammar’s worth of data has been collected. It explains what constitutes a valid family, what amount and kinds of documentary data are sufficient, when a language is considered extinct, and more. It is hoped that the survey will be useful in setting priorities for documenta- tion fieldwork, in particular for those documentation efforts whose underlying goal is to understand linguistic diversity. 1. InTroducTIon. There are several legitimate reasons for pursuing language documen- tation (cf. Krauss 2007 for a fuller discussion).1 Perhaps the most important reason is for the benefit of the speaker community itself (see Voort 2007 for some clear examples). Another reason is that it contributes to linguistic theory: if we understand the limits and distribution of diversity of the world’s languages, we can formulate and provide evidence for statements about the nature of language (Brenzinger 2007; Hyman 2003; Evans 2009; Harrison 2007). From the latter perspective, it is especially interesting to document lan- guages that are the most divergent from ones that are well-documented—in other words, those that belong to unrelated families. I have conducted a survey of the documentation of the language families of the world, and in this paper, I will list the least-documented ones. -

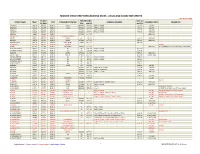

Residential Resurfacing List

MISSION VIEJO STREET RESURFACING INDEX - LOCAL AND COLLECTOR STREETS Rev. DEC 31, 2020 TB MAP RESURFACING LAST AC STREET NAME TRACT TYPE COMMUNITY/OWNER ADDRESS NUMBERS PAVEMENT INFO COMMENTS PG GRID TYPE MO/YR MO/YR ABADEJO 09019 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 28241 to 27881 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABADEJO 09018 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 27762 to 27832 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABANICO 09566 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27551 to 27581 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABANICO 09568 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27541 to 27421 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABEDUL 09563 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 .35AC/NS ABERDEEN 12395 922 C7 PRIVATE HIGHLAND CONDOS -- ABETO 08732 892 D5 PUBLIC MVEA AC JUL 15 JUL 15 .35AC/NS ABRAZO 09576 892 D3 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ACACIA COURT 08570 891 J6 PUBLIC TIMBERLINE TRMSS OCT 14 AUG 08 ACAPULCO 12630 892 F1 PRIVATE PALMIA -- GATED ACERO 79-142 892 A6 PUBLIC HIGHPARK TRMSS OCT 14 .55AC/NS 4/1/17 TRMSS 40' S of MAQUINA to ALAMBRE ACROPOLIS DRIVE 06667 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24582 to 24781 AUG 08 ACROPOLIS DRIVE 07675 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24801 to 24861 AUG 08 ADELITA 09078 892 D4 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ADOBE LANE 06325 922 C1 PUBLIC MVSRC RPMSS OCT 17 AUG 08 .17SAC/.58AB ADONIS STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24161 to 24232 SEP 14 ADONIS STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24101 to 24152 SEP 14 ADRIANA STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AEGEA STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AGRADO 09025 922 D1 PUBLIC OVGA AC AUG 18 AUG 18 .4AC/NS AGUILAR 09255 892 D1 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 PINAVETE -

TURBANS and TOP HATS Indian Interpreters in the Colony of Natal

TURBANS AND TOP HATS Indian Interpreters in the Colony of Natal, 1880-1910 by PRINISHA BADASSY A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Social Science – Honours in the Department of Historical Studies, Faculty of Human Science, University of Natal 2002 University of Natal Abstract TURBANS AND TOP HATS Indian Interpreters in the Colony of Natal, 1880-1910 by PRINISHA BADASSY Supervised by: Professor Jeff Guy Department of Historical Studies This dissertation is concerned with an historical examination of Indian Interpreters in the British Colony of Natal during the period, 1880 to 1910. These civil servants were intermediaries between the Colonial State and the wider Indian population, who apart from the ‘Indentureds’, included storekeepers, traders, politicians, railway workers, constables, court messengers, teachers and domestic servants. As members of an Indian elite and the Natal Civil Service, they were pioneering figures in overcoming the shackles of Indenture but at the same time they were active agents in the perpetuation of colonial oppression, and hegemonic imperialist ideas. Theirs was an ambiguous and liminal position, existing between worlds, as Occidentals and Orientals. Contents Acknowledgements iii List of Images iv List of Tables v List of Abbreviations vi Introduction 8 Chapter One – Indenture, Interpreters and Empire 13 Chapter Two – David Vinden 30 Chapter Three – Cows and Heifers 51 Chapter Four – A Diabolical Conspiracy 74 Conclusion 94 Appendix 98 Bibliography 124 Acknowledgments Out of a sea-bed of my search years I have put together again a million fragments of my brother’s ancient mirror… and as I look deep into it I see a million shades of fractured brown, merging into an unstoppable tide… David Campbell The history of Indians in Natal is one that is incomplete and developing. -

Grammar 03M Hindi'jstani' Language

G R A M M A R 03 m ' ' H I N D IJ S TA N I L A N G U A G E , IN T HE ORIENTA L A ND ROMA N C A RA CTER H , W ITH I I NUM E RO US COP PE R-P LATE ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE P E RSIAN A ND DEVANAGARI S Y STEM S OF ALP HABETIC V V BITING a m Is m TO en , A COPIOUS SELECTIONOF EASY EXTRACTS FOR READING, IN T HE I-A A BI A ND D A AGA I A A PERS R C EV N R CH R CTERS, FORM IN G A C OMP LET E IN TR ODUCTION T O u mTori-ma in; A N D BAGH- O-BAHAR ; W H TOG ETHER. IT A V O C A BU L A R Y O F A L L T H E O R D W S , AND VARIOUS EXP LAN ATORY NOTm A NEW DI IO E T N . N A N FORBES D BY DU C L . , L . , ' PROF SS OR O, OBIRH‘I‘AL N GUAG S ND T R ATU R mKIN G S C O G ONDON “ HE RB 0 ! E LA E A LI E E LLE E , L ; O ABIA TIO S OC Y OF GR BR N ND ND THE R Y A T T TA R BI O. L IE EA I I A I ELA . “ E B rmr u n s u n g mmA cormrnr “ ro an a n mmA N NT R ANC mo m me me n E E . -

DOWNLOAD Primerang Bituin

A publication of the University of San Francisco Center for the Pacific Rim Copyright 2006 Volume VI · Number 1 15 May · 2006 Special Issue: PHILIPPINE STUDIES AND THE CENTENNIAL OF THE DIASPORA Editors Joaquin Gonzalez John Nelson Philippine Studies and the Centennial of the Diaspora: An Introduction Graduate Student >>......Joaquin L. Gonzalez III and Evelyn I. Rodriguez 1 Editor Patricia Moras Primerang Bituin: Philippines-Mexico Relations at the Dawn of the Pacific Rim Century >>........................................................Evelyn I. Rodriguez 4 Editorial Consultants Barbara K. Bundy Hartmut Fischer Mail-Order Brides: A Closer Look at U.S. & Philippine Relations Patrick L. Hatcher >>..................................................Marie Lorraine Mallare 13 Richard J. Kozicki Stephen Uhalley, Jr. Apathy to Activism through Filipino American Churches Xiaoxin Wu >>....Claudine del Rosario and Joaquin L. Gonzalez III 21 Editorial Board Yoko Arisaka The Quest for Power: The Military in Philippine Politics, 1965-2002 Bih-hsya Hsieh >>........................................................Erwin S. Fernandez 38 Uldis Kruze Man-lui Lau Mark Mir Corporate-Community Engagement in Upland Cebu City, Philippines Noriko Nagata >>........................................................Francisco A. Magno 48 Stephen Roddy Kyoko Suda Worlds in Collision Bruce Wydick >>...................................Carlos Villa and Andrew Venell 56 Poems from Diaspora >>..................................................................Rofel G. Brion -

Burmese, a Grammar of (Soe).Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. A GRAMMAR OF BURMESE by MYINTSOE A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Linguistics and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment o f the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 1999 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

KONKANI's OWN Devanagarl SCR1PT

KONKANI’S OWN DEVANAGARl SCR1PT : THE JESUIT CONTRIBUTION by Mariano Jose Dias Explicit evidence to the effect that Devanagari is the natural script of the Konkani language, comes from none other than Jesuit sources in Goa, in the 16th century. This was dealt with by this writer in his article “Liturgical books in Devanagari Konkani”, in Renovaςão, 25 (1995), pp.203-204. The dynamic organizer of Jesuit missions in the East Visitor Alessandro Valignano (1539- 1606) was keen that Konkani language be learnt in its own script that could be none other than Devanagari, then called letra da terra. It is sufficient to recall what the chronicler of the Society Fr. Francisco de Sousa ( ? -1712) recorded in his Oriente Conquistado (Lisboa,1710) 2nd Part C.I. Div.II, 9, Bombay edition, 1886: "The Visitor ordered that eight scholastics learning Moral theology, be relieved from any other ministry so that they speak only in Konkani among themselves and the Rector ensured strict observance of this order: at certain time during the day they would practice by talking to local people and learn to read and write in the script of the place" (Ao Collegio de Salsete se applicaram este anno oito Irmãos moralistas ao estudo da lingua Canarina, tão necessaria para a cultura dos Christãos e conversão dos gentios. Ordenou o Padre Visitador, que os desoccupassem de qualquer outro ministerio, que não fallassem entre si senão na lingua da terra, e o Padre Reitor era exactissimo em fazer observar esta ordem: que todos os dias praticassem com os naturaes a certas__horas determinadas, que aprendessem a ler e escrever nos proprios caracteres do paiz..). -

The Absent Vedas

The Absent Vedas Will SWEETMAN University of Otago The Vedas were first described by a European author in a text dating from the 1580s, which was subsequently copied by other authors and appeared in transla- tion in most of the major European languages in the course of the seventeenth century. It was not, however, until the 1730s that copies of the Vedas were first obtained by Europeans, even though Jesuit missionaries had been collecting Indi- an religious texts since the 1540s. I argue that the delay owes as much to the rela- tive absence of the Vedas in India—and hence to the greater practical significance for missionaries of other genres of religious literature—as to reluctance on the part of Brahmin scholars to transmit their texts to Europeans. By the early eighteenth century, a strange dichotomy was apparent in European views of the Vedas. In Europe, on the one hand, the best-informed scholars believed the Vedas to be the most ancient and authoritative of Indian religious texts and to preserve a monotheistic but secret doctrine, quite at odds with the popular worship of multiple deities. The Brahmins kept the Vedas, and kept them from those outside their caste, especially foreigners. One or more of the Vedas was said to be lost—perhaps precisely the one that contained the most sublime ideas of divinity. By the 1720s scholars in Europe had begun calling for the Vedas to be translated so that this secret doctrine could be revealed, and from the royal library in Paris a search for the texts of the Vedas was launched. -

Keywords of Identity, Race, and Human Mobility in Early Modern

CONNECTED HISTORIES IN THE EARLY MODERN WORLD Das, Melo, SmithDas, & Working Melo, in Early Modern England Modern Early in Mobility Human and Race, Identity, of Keywords Nandini Das, João Vicente Melo, Haig Z. Smith, and Lauren Working Keywords of Identity, Race, and Human Mobility in Early Modern England Keywords of Identity, Race, and Human Mobility in Early Modern England Connected Histories in the Early Modern World Connected Histories in the Early Modern World contributes to our growing understanding of the connectedness of the world during a period in history when an unprecedented number of people—Africans, Asians, Americans, and Europeans—made transoceanic or other long distance journeys. Inspired by Sanjay Subrahmanyam’s innovative approach to early modern historical scholarship, it explores topics that highlight the cultural impact of the movement of people, animals, and objects at a global scale. The series editors welcome proposals for monographs and collections of essays in English from literary critics, art historians, and cultural historians that address the changes and cross-fertilizations of cultural practices of specific societies. General topics may concern, among other possibilities: cultural confluences, objects in motion, appropriations of material cultures, cross-cultural exoticization, transcultural identities, religious practices, translations and mistranslations, cultural impacts of trade, discourses of dislocation, globalism in literary/visual arts, and cultural histories of lesser studied regions (such as the -

Imagines-Number-2-2018-August

Imagines è pubblicata a Firenze dalle Gallerie degli Uffizi Direttore responsabile Eike D. Schmidt Redazione Dipartimento Informatica e Strategie Digitali Coordinatore Gianluca Ciccardi Coordinatore delle iniziative scientifiche delle Gallerie degli Uffizi Fabrizio Paolucci Hanno lavorato a questo numero Andrea Biotti, Patrizia Naldini, Marianna Petricelli Traduzioni: Eurotrad con la supervisione di Giovanna Pecorilla ISSN n. 2533-2015 2 august 2018 index n. 2 (2018, August) 6 EIKE SCHMIDT Digital reflexions 10 SILVIA MASCALCHI School/Work programmes at the Uffizi Galleries. Diary of an experience in progress 20 SIMONE ROVIDA When Art Takes Centre Stage. Uffizi Live and live performance arts as a means to capitalise on museum resources 38 ELVIRA ALTIERO, FEDERICA CAPPELLI, LUCIA LO STIMOLO, GIANLUCA MATARRELLI An online database for the conservation and study of the Uffizi ancient sculptures 52 ALESSANDRO MUSCILLO The forgotten Grand Duke. The series of Medici-Lorraine busts and their commendation in the so-called Antiricetto of the Gallery of Statues and Paintings 84 ADELINA MODESTI Maestra Elisabetta Sirani, “Virtuosa del Pennello” 98 CARLA BASAGNI PABLO LÓPEZ MARCOS Traces of the “Museo Firenze com’era in the Uffizi: the archive of Piero Aranguren (Prato 1911- Florence 1988), donated to the Library catalog 107 FABRIZIO PAOLUCCI ROMAN ART II SEC. D. C., Sleepimg Ariadne 118 VINCENZO SALADINO ROMAN ART, Apoxyomenos (athlete with a Scraper) 123 DANIELA PARENTI Spinello Aretino, Christ Blessing Niccolò di Pietro Gerini, Crocifixion 132 ELVIRA ALTIERO Niccolò di Buonaccorso, Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple n.2 | august 2018 Eike Schmidt DIGITAL REFLEXIONS 6 n Abbas Kiarostami’s film Shirin (2008), sing questions of guilt and responsibility for an hour and a half we see women – would have been superimposed upon Iin a theatre in Iran watching a fictio- its famous first half, the action-packed nal movie based on the tragic and twi- Nibelungenlied (Song of the Nibelungs).