Defining Goan Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

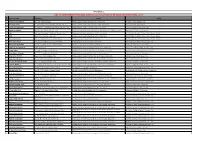

Wholesale List at Bardez

BARDEZ Sr.No Name & Address of The Firm Lic. No. Issued Dt. Validity Dt. Old Lic No. 1 M/s. Rohit Enterprises, 5649/F20B 01/05/1988 31/12/2021 913/F20B 23, St. Anthony Apts, Mapuca, Bardez- Goa 5651/F21B 914/F21B 5650/20D 24/20D 2 M/s. Shashikant Distributors., 6163F20B 13/04/2005 18/11/2019 651/F20B Ganesh Colony, HNo.116/2, Near Village 6164/F20D 652/F21B Panchyat Punola, Ucassim , Bardez – Goa. 6165/21B 122/20D 3 M/s. Raikar Distributors, 5022/F20B 27/11/2014 26/11/2019 Shop No. E-4, Feira Alto, Saldanha Business 5023/F21B Towers, Mapuca – Goa. 4 M/s. Drogaria Ananta, 7086/F20B 01/04/2008 31/03/2023 449/F20B Joshi Bldg, Shop No.1, Mapuca, Bardez- Goa. 7087/F21B 450/F21B 5 M/s. Union Chemist& Druggist, 5603/F20B 25/08/2011 24/08/2021 4542/F20B Wholesale (Godown), H No. 222/2, Feira Alto, 5605/F21B 4543/F21B Mapuca Bardez – Goa. 5604/F20D 6 M/s. Drogaria Colvalcar, 5925/F20D 09/11/2017 09/11/2019 156/F20B New Drug House, Devki Krishna Nagar, Opp. 6481/F20 B 157/F21B Fomento Agriculture, Mapuca, Bardez – Goa. 6482/F21B 121/F20D 5067/F20G 08/11/2022 5067/20G 7 M/s. Sharada Scientific House, 5730/F20B 07/11/1990 31/12/2021 1358/F20B Bhavani Apts, Dattawadi Road, Mapuca Goa. 5731/F21B 1359/F21B 8 M/s. Valentino F. Pinto, 6893/F20B 01/03/2013 28/02/2023 716/F20B H. No. 5/77A, Altinho Mapuca –Goa. 6894/F21B 717/F21B 9 M/s. -

Women´S Writing and Writings on Women In

WOMEN´S WRITING AND WRITINGS ON WOMEN IN THE GOAN MAGAZINE O ACADÉMICO (1940– 1943)1 A ESCRITA DE MULHERES E A ESCRITA SOBRE MULHERES NA REVISTA GOESA O ACADÉMICO (1940 – 1943) VIVIANE SOUZA MADEIRA2 ABSTRACT: This article discusses some texts, written by women, as well as texts on women, written by men, in the Goan magazineO Académico (1940-1943). Even though O Académico is not particularly aimed at women’s readership, but at a broader audience – the “Goan youth” – it contains articles that deal with the question of women in the spheres of science, politics and literature. As one of the magazine’s objectives was to “emancipate Goan youth intellectually”, we understand that young women’s education was also within their scope, focusing on the question of women’s roles. The Goan intelligentsia that made up the editorial board of the publication revealed their desire for modernization by showing their preoccupation with forward-looking ideas and by providing a space for women to publish their texts. KEYWORDS: Women’s writing, Men writing on women, Periodical Press,O Académico, Goa. RESUMO: Este artigo discute textos escritos sobre mulheres, por homens e por mulheres, na revista goesa O Académico (1940-1943). Embora não tenha sido particularmente voltada as leitoras, mas a um público mais amplo – a “juventude goesa” – a revista contém artigos que abordam a questão da mulher nas esferas da ciência, da política e da literatura. Como um dos seus objetivos era “emancipar intelectualmente a juventude goesa”, entendemos que a educação das jovens de Goa estava no escopo da publicação, focando também na questão dos papéis que essas mulheres cumpriam em sua sociedade. -

LIST of ENDOWMENT for XXIX ANNUAL CONVOCATION to BE HELD on 25TH APRIL, 2017 Sr

GOA UNIVERSITY TALEIGAO PLATEAU - GOA LIST OF ENDOWMENT FOR XXIX ANNUAL CONVOCATION TO BE HELD ON 25TH APRIL, 2017 Sr. Name of Candidate Endowment Criteria College No. 1 Palekar Prerna Sudhakar Shri. N. D. Naik Scholarship obtaining highest marks in Konkani at B.A. Examination St. Xaviers College, Mapusa - Goa. 2 Anil Kumar Yadav Shri Meghashyam Parshuram Deshprabhu Paritoshik obtaining highest marks in Portuguese at the M.A. examination Dept. of Portugese, Goa University 3 Khwaja Sana Najmuddin Smt. Mirabai Rudraji Sardessai (Vimalatai Usgaonkar) Prize obtaining highest marks at the Final B.Com. Examination S.S.Dempo College of Economics, Cujira 4 Aswathi R Jagadish Venkatesh Govind Sinai Virginkar Prize obtaining highest marks at the Final year M.A. examination in the subject of French Department of French, Goa University 5 Jyoti Smt. Manju Ghanashyam Nagarsekar Memorial Prize obtaining highest marks in English at the B.A. examination Smt. Parvatibai Chowgule College of Arts & Science, Margao 6 Jyoti Late Prof. Jose Carmelo Coelho Prize obtaining highest marks in English at the B.A. examination Smt. Parvatibai Chowgule College of Arts & Science, Margao 7 Keni Tanya Ashish Lions Club of Margao Silver Jubilee Scholarship obtaining highest marks at the B.A. examination Smt. Parvatibai Chowgule College of Arts & Science, Margao 8 Nadar Annie Princy Lions Club of Margao Silver Jubilee Scholarship obtaining highest marks at the B.Sc. Examination Carmel College for Women, Nuvem, Salcete Goa 9 Khwaja Sana Najmuddin Lions Club of Margao Silver Jubilee Scholarship obtaining highest marks at the B.Com. Examination S.S.Dempo College of Economics, Cujira 10 Prabhu Gaunker Diksha R. -

Heritage(S) of Portuguese Influence in the Indian Ocean Borders Syllabus

Walter Rossa Visitant Research Professor of the Cunha Rivara Chair at Goa University 15 - 23 July 2019 Heritage(s) of Portuguese Influence in the Indian Ocean Borders a 12 hours course + a Public Lecture syllabus [email protected] programme — 6 topics in sessions of 2 hours day 15 presentation 1. heritage/ heritages: international concepts and the specificity of the Heritage(s) of Portuguese Influence day 16 2. European cultural matrixes on an Atlantic-Mediterranean periphery; the arts in the framework of a gloBal market appeal day 17 3. the learning in the building of a first global Empire: factories, fortification, cities day 18 4. catholic architecture day 19 5. the Breakup of the 1st Portuguese Empire and the dawn of a Goan identity day 23 6. values, conflict and risks of Goa's Portuguese Influence built Heritage a seminar based on students essays preliminary presentations W. Rossa | Heritage(s) of Portuguese Influence on the Indian Ocean borders | Cunha Rivara Chair at Goa University | 2019 2 requirements and grading — To merit grading, the student must participate, at least, in the first and last sessions as well as in one other session. Students must also present for discussion and submit a circa 1.000 words essay developed during the course under the professor's guidance. — The essay themes will sprout from the research interests declared on the first session, but should fit under the broader concept of heritage values, taking into account risks contexts. — The essays must be delivered in pdf until 25 August. Previous presentation and discussion will be made during the last session seminar. -

If Goa Is Your Land, Which Are Your Stories? Narrating the Village, Narrating Home*

If Goa is your land, which are your stories? Narrating the Village, Narrating Home* Cielo Griselda Festinoa Abstract Goa, India, is a multicultural community with a broad archive of literary narratives in Konkani, Marathi, English and Portuguese. While Konkani in its Devanagari version, and not in the Roman script, has been Goa’s official language since 1987, there are many other narratives in Marathi, the neighbor state of Maharashtra, in Portuguese, legacy of the Portuguese presence in Goa since 1510 to 1961, and English, result of the British colonization of India until 1947. This situation already reveals that there is a relationship among these languages and cultures that at times is highly conflictive at a political, cultural and historical level. In turn, they are not separate units but are profoundly interrelated in the sense that histories told in one language are complemented or contested when narrated in the other languages of Goa. One way to relate them in a meaningful dialogue is through a common metaphor that, at one level, will help us expand our knowledge of the points in common and cultural and * This paper was carried out as part of literary differences among them all. In this article, the common the FAPESP thematic metaphor to better visualize the complex literary tradition from project "Pensando Goa" (proc. 2014/15657-8). The Goa will be that of the village since it is central to the social opinions, hypotheses structure not only of Goa but of India. Therefore, it is always and conclusions or recommendations present in the many Goan literary narratives in the different expressed herein are languages though from perspectives that both complement my sole responsibility and do not necessarily and contradict each other. -

Industrial Policy Daman & Diu and Dadra & Nagar Haveli

INDUSTRIAL POLICY DAMAN & DIU AND DADRA & NAGAR HAVELI SOCIO -DEMOGRAPHIC DEVELOPMENT INDICES S.N. INDICATOR DAMAN & DIU DNH A POPULATION Total Population (2011) 2,43,247 3,42,853 B LITERACY Male Literacy 2011 91.54 % 85.20 % Female Literacy 2011 79.54 % 64.30 % Total Literacy 2011 87.10 % 76.20 % C HOTELS Daman Diu DNH Total 93 60 106 Rooms available 4272 2336 1539 A’ Category Hotels 22 07 06 ‘A’ Category Rooms 961 274 435 PROFILE OF DAMAN AND DIU Head Quarter : Daman Parliament Constituency : 01 Area: Daman (72 sq.km.) : Diu (40 sq.km.) Diu is an Island near Junagarh ( Kachchh , GJ) INDUSTRIAL PROFILE DAMAN & DIU Industrial Estates : 39 Industrial Units : 3292 Capital Investment : 12,146 Cr. Employment in Industries : 83,143 Key Sectors: Plastics , Pharmaceutical, Chemical & Chemical Products, Textiles, Electrical Conductors, Basic Metals, Paper and Paper Products, Tourism etc.. INDUSTRIAL PROFILE Computers, Electroni Other cs & Optical Manufacturing, 8.9% Products, Machinery & Equipments and Beverages, 4.4% Paper & Paper Products, 2.7% Textiles, 2.8% Electrical Equipments, 33.2% Basic Metals, 2.8% Wearing Apparels, 4.9% Chemical & Chemical Products, 9.0% Plastic Products, 18.3% Pharmaceuticals,13% PROFILE OF DADRA & NAGAR HAVELI Head Quarter : Silvassa District: 01 Parliament Constituency : 01 Area : 491 sq. km. INDUSTRIAL PROFILE DADRA & NAGAR HAVELI Industrial Estates : 49 Industrial Units : 3175 Capital Investment : Rs. 20,000 Cr. Employment in Industries : 1,20,000 Key Sectors: • 80% of India`s Texturising Yarn is Contributed -

GOA UNIVERSITY Taleigao Plateau - Goa List of Rankers for the 31St Annual Convocation Gende Sr

GOA UNIVERSITY Taleigao Plateau - Goa List of Rankers for the 31st Annual Convocation Gende Sr. No. Degree / Exam Seat No. PR. NO. Name of Students Year of Exam CGPA/CPI Marks Perc Class /Grade Add 1 Ph. No. r FLAT NO 4 KAPIL BUILDING HOUSING BOARD COLONY 1 M.A. English EG-1316 201303249 F DO REGO MARIA DAZZLE SAVIA April, 2018 8.60 1496/2000 74.80 A FIRST 9881101875 GHANESHPURI MAPUSA BARDEZ GOA. 403507 HNO.1650 VASVADDO BENAULIM SALCETTE GOA. 2 EG-0116 201302243 F AFONSO VALENCIA SHAMIN April, 2018 8.49 1518/2000 75.90 A SECOND 8322770494 403716 3 EG-4316 201609485 M RODRIGUES AARON SAVIO April, 2018 8.23 1432/2000 71.60 A THIRD DONA PAULA, GOA. 403004 9763110945 1196/A DOMUS AUREA NEOVADDO GOGOL FATORDA 4 M.A. Portuguese PR-0216 201606566 M COTTA FRANZ SCHUBERT AGNELO DE MIRANDA April, 2018 9.29 1643/2000 82.15 A+ FIRST 8322759285 MARGAO GOA. 403602 HOUSE NO. 1403 DANGVADDO BENAULIM SALCETE 5 PR-0616 201606570 F VAS SANDRA CARMEN April, 2018 8.25 1465/2000 73.25 A SECOND 9049558659 GOA. 403716 F1 F2 SANTA CATARIA RESIDENCY SERAULIM SALCETE 6 PR-0316 201302493 F DE SCC REBELO NADIA MARIA DE JESUS April, 2018 7.58 1303/2000 65.15 B+ THIRD 8322789027 GOA. 403708 B-10 ADELVIN APTS SHETYEWADO DULER MAPUSA 7 M.A. Hindi HN-3216 201303177 F VERLEKAR MAMATA DEEPAK April, 2018 8.34 1460/2000 73.00 A FIRST 9226193838 BARDEZ GOA. 403507 H. NO. GUJRA BHAT TALALIM CURCA TISWADI GOA. 8 HN-1416 201307749 F MENKA KUMARI April, 2018 7.50 1281/2000 64.05 B+ SECOND 9763358712 403108 9 HN-3016 201303949 M VARAK DEEPAK PRABHAKAR April, 2018 7.36 1292/2000 64.60 B+ THIRD VALKINI COLONY NO. -

International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage

Abstract Volume: International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage International Conference of the International Association for Asian Heritage 2011 Abstract Volume: Intenational Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage 21th - 23rd August 2013 Sri Lanka Foundation, Colombo, Sri Lanka Editor Anura Manatunga Editorial Board Nilanthi Bandara Melathi Saldin Kaushalya Gunasena Mahishi Ranaweera Nadeeka Rathnabahu iii International Conference of the International Association for Asian Heritage 2011 Copyright © 2013 by Centre for Asian Studies, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka. First Print 2013 Abstract voiume: International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage Publisher International Association for Asian Heritage Centre for Asian Studies University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka. ISBN 978-955-4563-10-0 Cover Designing Sahan Hewa Gamage Cover Image Dwarf figure on a step of a ruined building in the jungle near PabaluVehera at Polonnaruva Printer Kelani Printers The views expressed in the abstracts are exclusively those of the respective authors. iv International Conference of the International Association for Asian Heritage 2011 In Collaboration with The Ministry of National Heritage Central Cultural Fund Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology Bio-diversity Secratariat, Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy v International Conference of the International Association for Asian Heritage 2011 Message from the Minister of Cultural and Arts It is with great pleasure that I write this congratulatory message to the Abstract Volume of the International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage, collaboratively organized by the Centre for Asian Studies, University of Kelaniya, Ministry of Culture and the Arts and the International Association for Asian Heritage (IAAH). It is also with great pride that I join this occasion as I am associated with two of the collaborative bodies; as the founder president of the IAAH, and the Minister of Culture and the Arts. -

An Issue of Mopa International Airport

ISSN No. 2394-5982 mySOCIETY X (1-2), 2015-16 ©University of Mysore Research Article http://mysociety.uni-mysore.ac.in LAND, DEVELOPMENT AND RESISTANCE: AN ISSUE OF MOPA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT - ■r'fyajbuM Ldr /P c ABSTRACT The changing development paradigm in the post-reform period brought along with growth new challenges and concerns. The pressure on land, the question of rehabilitation and resettlement, environmental degradation, growing inequalities are some such concerns. The mega projects initiated by both Central as well as Sfafe government are putting pressure on land and threatening the livelihood of people and environment. Goa is not immune to such developments. The article is concerned with the process of land acquisition to build international airport in Goa and in the course o f action affecting environment and livelihood of people. The article argues while such acquisition is necessary for development, its success depends upon consultation with stakeholders prior to such decisions and well thought out compensation and rehabilitation packages which are lacking in the process of land acquisition. Development discourse in the post reform period brought along with growth host of challenges. One of the major issue in the development discourse revolves around land acquisition and displacement. The increasing number of mega projects are putting pressure on the existing land and environment resultingin protest against such projects throughout the country. Goa being very small the stakes are high. In recent years Goa also witnessed number of protests against the planning and development of projects which risked the land, livelihood and environment. One such protest is the protest against construction of Mopa International Airport in PernemTaluka of Goa. -

Valvanti River Action Plan

The River Rejuvenation Committee Government of Goa Name of the work: Preparation of Action Plan for Rejuvenation of Polluted Stretches of Rivers in Goa Action Plan Report on Valvanti River March 2019 River Rejuvenation Committee (RRC), Goa River Rejuvenation Action Plan-Valvanti River Contents Executive Summary: 4 Action Plan Strategies: 9 1. Brief about Valvanti River: 14 1.1. River Valvanti: .......................................................................................................................14 1.2. Water Quality of River Valvanti: ............................................................................................15 1.3. Water Sampling Results:.......................................................................................................16 1.4. Data Analysis and interpretation: ..........................................................................................17 1.5. Action Plan Strategies:..........................................................................................................18 1.6. Major Concerns:....................................................................................................................18 2. Source Control: 19 3. River Catchment Management: 20 4. Flood Plain Zone: 21 5. Greenery Development- Plantation Plan: 22 6. Ecological / Environmental Flow (E-Flow): 23 7. Action Plan Strategies: 25 7.1. Conclusion & Remark: ..........................................................................................................27 1 River Rejuvenation Committee -

The Religious Lifeworlds of Canada's Goan and Anglo-Indian Communities

Brown Baby Jesus: The Religious Lifeworlds of Canada’s Goan and Anglo-Indian Communities Kathryn Carrière Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the PhD degree in Religion and Classics Religion and Classics Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Kathryn Carrière, Ottawa, Canada, 2011 I dedicate this thesis to my husband Reg and our son Gabriel who, of all souls on this Earth, are most dear to me. And, thank you to my Mum and Dad, for teaching me that faith and love come first and foremost. Abstract Employing the concepts of lifeworld (Lebenswelt) and system as primarily discussed by Edmund Husserl and Jürgen Habermas, this dissertation argues that the lifeworlds of Anglo- Indian and Goan Catholics in the Greater Toronto Area have permitted members of these communities to relatively easily understand, interact with and manoeuvre through Canada’s democratic, individualistic and market-driven system. Suggesting that the Catholic faith serves as a multi-dimensional primary lens for Canadian Goan and Anglo-Indians, this sociological ethnography explores how religion has and continues affect their identity as diasporic post- colonial communities. Modifying key elements of traditional Indian culture to reflect their Catholic beliefs, these migrants consider their faith to be the very backdrop upon which their life experiences render meaningful. Through systematic qualitative case studies, I uncover how these individuals have successfully maintained a sense of security and ethnic pride amidst the myriad cultures and religions found in Canada’s multicultural society. Oscillating between the fuzzy boundaries of the Indian traditional and North American liberal worlds, Anglo-Indians and Goans attribute their achievements to their open-minded Westernized upbringing, their traditional Indian roots and their Catholic-centred principles effectively making them, in their opinions, admirable models of accommodation to Canada’s system. -

Official ~79Gazette Government of Goa

IReg. NO,'GRlRNP/GOAl32I 12003 YEAR OF THE CHILD I IRNI No. GOAENGI20021641 0 I Panaji,7th August, 2003 (Sravana 16,1925)' . SERIES II No.19 . .,.'" OFFICIAL ~79GAZETTE GOVERNMENT OF GOA Note:- There are 'lWo Supplements and One Extraordinary Corrigendum issue to- the Official Gazette, Series II, No. 18.- dated :31·7·2003 as follows:· NO.3/201/SCD/D.Agri/2002·03/323 Read:· Notification No. 3/201/SCD/D.Agri/2002-03/ 1) Supplement dated 31·7·2003 from pages 299 to 328 /650 dated 13th January,; 2003. regarding -Notification -fiom Department of'Law and Judiciary (Legal Affairs Division) The Member of the State Level High Power Committee at Sr. No. 4 of the ahove notification may be read as 2) Extraordinary dated 1·8·2003 from pages 329 to 330 Superintending Engineer-! (WRD) instead of regarding Order from Department of Science, Superintending Engineer (WRD). Technology & Environment. By order and in the name of the Governor of Goa. 3) Supplement No.2 dated 6·8·2003 from pages 331 to 334 R. G. Joshi, Director of Agriculture & Ex-Officio Joint regarding Notification's and Corrigendum from Secretary: , Department of Revenue. Panaji, 24th July,' 2003 .. GOVERNMENT OF GOA --+++-'- Department of Agriculture Department of Finance Revenue & Control Division Directorate of Agriculture Order Order .. " No. 17/16/2002-Fin(R&C)-Part No. 24-83-AGR/2003/191 Gov~rnment i~ pleased to" con:stitut~ a cQinmitt~e of the following Members of the. Legislative Assembly to On the recommendations.,o{ the Goa Public SerVice go into disputes which arose out of the State Lottery Commission Vide their letter No.