DOWNLOAD Primerang Bituin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Southern Denmark

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN DENMARK THE CHRISTIAN KINGDOM AS AN IMAGE OF THE HEAVENLY KINGDOM ACCORDING TO ST. BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY INSTITUTE OF HISTORY, CULTURE AND CIVILISATION CENTRE FOR MEDIEVAL STUDIES BY EMILIA ŻOCHOWSKA ODENSE FEBRUARY 2010 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In my work, I had the privilege to be guided by three distinguished scholars: Professor Jacek Salij in Warsaw, and Professors Tore Nyberg and Kurt Villads Jensen in Odense. It is a pleasure to admit that this study would never been completed without the generous instruction and guidance of my masters. Professor Salij introduced me to the world of ancient and medieval theology and taught me the rules of scholarly work. Finally, he encouraged me to search for a new research environment where I could develop my skills. I found this environment in Odense, where Professor Nyberg kindly accepted me as his student and shared his vast knowledge with me. Studying with Professor Nyberg has been a great intellectual adventure and a pleasure. Moreover, I never would have been able to work at the University of Southern Denmark if not for my main supervisor, Kurt Villads Jensen, who trusted me and decided to give me the opportunity to study under his kind tutorial, for which I am exceedingly grateful. The trust and inspiration I received from him encouraged me to work and in fact made this study possible. Karen Fogh Rasmussen, the secretary of the Centre of Medieval Studies, had been the good spirit behind my work. -

Spanish Heritage.Pages

Heritage in Micronesia SPANISH PROGRAM FOR CULTURAL COOPERATION with the collaboration of the GUAM PRESERVATION TRUST and the HISTORIC RESOURCES DIVISION, DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION Spanish Spanish Program for Cultural Cooperation Conference Spanish Heritage in Micronesia Inventory and Assessment October 16, 2008 Hyatt Regency, Tumon Guam Spanish Program for Cultural Cooperation with the collaboration of the Guam Preservation Trust and the Historic Resources Division, Guam Department of Parks and Recreation Table of Contents Spanish Heritage in Micronesia: Inventory and Assessment 1 By Judith S. Flores, PhD Spanish Heritage Resources In The Mariana Islands 5 By Judith S. Flores, PhD The Archaeology of Spanish Period, Guam 11 By John A. Peterson Inventory and Assessment of Spanish Tangible Heritage in the Federated States of Micronesia 32 By Rufino Mauricio Heritage Preservation And Sustainability: Technical Recommendations And Community Participation 44 By Maria Lourdes Joy Martinez-Onozawa Historic Inalahan Field Workshop 52 By Judith S. Flores, PhD Spanish Heritage in Palau 61 By Filly Carabit and Errolflynn Kloulechad Spanish Heritage in Micronesia: Inventory and Assessment Introduction By Judith S. Flores, PhD President, Historic Inalahan Foundation, Inc. The second in a series of conferences funded by the Spanish Program for Cultural Cooperation (SPCC) opened in the Hyatt-Regency in Tumon, Guam on October 16, 2008. The first conference sponsored by SPCC was held the previous year in Guam on Nov. 14-15, 2007, entitled “Stonework Heritage in Micronesia”, organized by the Guam Preservation Trust. It brought together and introduced technical experts in Spanish stonework and Spanish heritage architects to a gathering of historic preservation officials and scholars who live and work in Guam and Micronesia. -

Early Colonial History Four of Seven

Early Colonial History Four of Seven Marianas History Conference Early Colonial History Guampedia.com This publication was produced by the Guampedia Foundation ⓒ2012 Guampedia Foundation, Inc. UOG Station Mangilao, Guam 96923 www.guampedia.com Table of Contents Early Colonial History Windfalls in Micronesia: Carolinians' environmental history in the Marianas ...................................................................................................1 By Rebecca Hofmann “Casa Real”: A Lost Church On Guam* .................................................13 By Andrea Jalandoni Magellan and San Vitores: Heroes or Madmen? ....................................25 By Donald Shuster, PhD Traditional Chamorro Farming Innovations during the Spanish and Philippine Contact Period on Northern Guam* ....................................31 By Boyd Dixon and Richard Schaefer and Todd McCurdy Islands in the Stream of Empire: Spain’s ‘Reformed’ Imperial Policy and the First Proposals to Colonize the Mariana Islands, 1565-1569 ....41 By Frank Quimby José de Quiroga y Losada: Conquest of the Marianas ...........................63 By Nicholas Goetzfridt, PhD. 19th Century Society in Agaña: Don Francisco Tudela, 1805-1856, Sargento Mayor of the Mariana Islands’ Garrison, 1841-1847, Retired on Guam, 1848-1856 ...............................................................................83 By Omaira Brunal-Perry Windfalls in Micronesia: Carolinians' environmental history in the Marianas By Rebecca Hofmann Research fellow in the project: 'Climates of Migration: -

Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States

Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States Winthrop D. Jordan1 Edited by Paul Spickard2 Editor’s Note Winthrop Jordan was one of the most honored US historians of the second half of the twentieth century. His subjects were race, gender, sex, slavery, and religion, and he wrote almost exclusively about the early centuries of American history. One of his first published articles, “American Chiaroscuro: The Status and Definition of Mulattoes in the British Colonies” (1962), may be considered an intellectual forerunner of multiracial studies, as it described the high degree of social and sexual mixing that occurred in the early centuries between Africans and Europeans in what later became the United States, and hinted at the subtle racial positionings of mixed people in those years.3 Jordan’s first book, White over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550–1812, was published in 1968 at the height of the Civil Rights Movement era. The product of years of painstaking archival research, attentive to the nuances of the thousands of documents that are its sources, and written in sparkling prose, White over Black showed as no previous book had done the subtle psycho-social origins of the American racial caste system.4 It won the National Book Award, the Ralph Waldo Emerson Prize, the Bancroft Prize, the Parkman Prize, and other honors. It has never been out of print since, and it remains a staple of the graduate school curriculum for American historians and scholars of ethnic studies. In 2005, the eminent public intellectual Gerald Early, at the request of the African American magazine American Legacy, listed what he believed to be the ten most influential books on African American history. -

Cebu 1(Mun to City)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Map of Cebu Province i Map of Cebu City ii - iii Map of Mactan Island iv Map of Cebu v A. Overview I. Brief History................................................................... 1 - 2 II. Geography...................................................................... 3 III. Topography..................................................................... 3 IV. Climate........................................................................... 3 V. Population....................................................................... 3 VI. Dialect............................................................................. 4 VII. Political Subdivision: Cebu Province........................................................... 4 - 8 Cebu City ................................................................. 8 - 9 Bogo City.................................................................. 9 - 10 Carcar City............................................................... 10 - 11 Danao City................................................................ 11 - 12 Lapu-lapu City........................................................... 13 - 14 Mandaue City............................................................ 14 - 15 City of Naga............................................................. 15 Talisay City............................................................... 16 Toledo City................................................................. 16 - 17 B. Tourist Attractions I. Historical........................................................................ -

New Spain and Early Independent Mexico Manuscripts New Spain Finding Aid Prepared by David M

New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts New Spain Finding aid prepared by David M. Szewczyk. Last updated on January 24, 2011. PACSCL 2010.12.20 New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts Table of Contents Summary Information...................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History.........................................................................................................................................3 Scope and Contents.......................................................................................................................................6 Administrative Information...........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory..................................................................................................................................... 9 - Page 2 - New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts Summary Information Repository PACSCL Title New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts Call number New Spain Date [inclusive] 1519-1855 Extent 5.8 linear feet Language Spanish Cite as: [title and date of item], [Call-number], New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts, 1519-1855, Rosenbach Museum and Library. Biography/History Dr. Rosenbach and the Rosenbach Museum and Library During the first half of this century, Dr. Abraham S. W. Rosenbach reigned supreme as our nations greatest bookseller. -

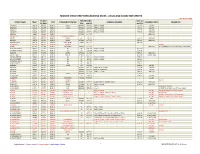

Residential Resurfacing List

MISSION VIEJO STREET RESURFACING INDEX - LOCAL AND COLLECTOR STREETS Rev. DEC 31, 2020 TB MAP RESURFACING LAST AC STREET NAME TRACT TYPE COMMUNITY/OWNER ADDRESS NUMBERS PAVEMENT INFO COMMENTS PG GRID TYPE MO/YR MO/YR ABADEJO 09019 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 28241 to 27881 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABADEJO 09018 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 27762 to 27832 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABANICO 09566 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27551 to 27581 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABANICO 09568 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27541 to 27421 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABEDUL 09563 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 .35AC/NS ABERDEEN 12395 922 C7 PRIVATE HIGHLAND CONDOS -- ABETO 08732 892 D5 PUBLIC MVEA AC JUL 15 JUL 15 .35AC/NS ABRAZO 09576 892 D3 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ACACIA COURT 08570 891 J6 PUBLIC TIMBERLINE TRMSS OCT 14 AUG 08 ACAPULCO 12630 892 F1 PRIVATE PALMIA -- GATED ACERO 79-142 892 A6 PUBLIC HIGHPARK TRMSS OCT 14 .55AC/NS 4/1/17 TRMSS 40' S of MAQUINA to ALAMBRE ACROPOLIS DRIVE 06667 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24582 to 24781 AUG 08 ACROPOLIS DRIVE 07675 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24801 to 24861 AUG 08 ADELITA 09078 892 D4 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ADOBE LANE 06325 922 C1 PUBLIC MVSRC RPMSS OCT 17 AUG 08 .17SAC/.58AB ADONIS STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24161 to 24232 SEP 14 ADONIS STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24101 to 24152 SEP 14 ADRIANA STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AEGEA STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AGRADO 09025 922 D1 PUBLIC OVGA AC AUG 18 AUG 18 .4AC/NS AGUILAR 09255 892 D1 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 PINAVETE -

Antonio De Mendoza; First Viceroy of Mexico. the Tinker Pamphlet

.4. DOCUMENT RESUME ED 114 227 RC 008' 850- AUTHOR Miller, Hubert J. TITLE Antonio de Mendola; First Viceroy of Mexico. The Tinker Pamphlet Series for the Teaching of.Mexican American Heritage. TB 73 NOTE 70p.; For related documents, see RC 008 851-853 AVAtLABL ROM' Mr. Al Ramirez, P.O. Box 471, Edinburg, Texas.78539 ($1.00) EDRS PRICE. MF-$0.76 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTO ji5*Administrator Background; American Indians; - *Biographies; Colonialism; Cultiral Education; Curriculum Enrichment; Curriculum Guides; Elementary Secondary Education; *Mexican.AmerieHistory; *Mexicaps; Resource Materials; Sociocultural Patterns; Vocabulait; *Western Civiliiation IDENTIFIERS *Mendoza (Antonio de) ABSTRACT .0 As Mexico's first viceroy, Antonio de Mendoza.s most noteworthy achievement was his laYing the basis of colonial government in New Spain which continued, with modifications, for 300. years. Although he was lenient in dealing with the shortcomingi of .his Indian and Spanish subjects; he took a'firm stand in dealing with the rebellious Indians in the Mixton War and the Cortes faction which threatened the Viceregal rule. His pridary concern was to keep New Spain for the crown while protecting the Indians from w#nt.and . inhumanity. Focusing o$ the institutions he founded and 'developed, this booklet provides a study of early Spanish colonial institutions. Although the biographical account is of secondary importance, the. description .of Hispanic colonial institutions arelPable'in presenting the Spaniards. colonization after the cconquest -ctica. applicAtion of the, material at both the elementary and 'se levels can be utilized in stimulating student discussionsa on the Merits and demerits of 2 colonial powers- -the English a the Spaniards. -

The Manila Galleon and the Opening of the Trans-Pacific West

Old Pueblo Archaeology Center presents The Manila Galleon and the Opening of the Trans-Pacific West A free presentation by Father Greg Adolf for Old Pueblo Archaeology Center’s “Third Thursday Food for Thought” Dinner Program Thursday September 19, 2019, from 6 to 8:30 p.m. This month’s program will be at Karichimaka Mexican Restaurant, 5252 S. Mission Rd., Tucson MAKE YOUR RESERVATION WITH OLD PUEBLO ARCHAEOLOGY CENTER: 520-798-1201 or [email protected] RESERVATIONS MUST BE REQUESTED AND CONFIRMED before 5 p.m. on the Wednesday before the program. The first of the galleons crossed the Pacific in 1565. The last one put into port in 1815. Yearly, for the two and a half centuries that lay between, the galleons made the long and lonely voyage between Manila in the Philippines and Acapulco in Mexico. No other commercial enterprise has ever endured so long. No other regular navigation has been so challenging and dangerous as this, for in its two hundred and fifty years, the ocean claimed dozens of ships and thousands of lives, and many millions in treasure. To the peoples of Spanish America, they were the “China Ships” or “Manila Galleons” that brought them cargoes of silks and spices and other precious merchandise of the Orient, forever changing the material culture of the Spanish Americas. To those in the Orient, they were the “Silver Ships” laden with Mexican and Peruvian pesos that were to become the standard form of currency throughout the Orient. To the Californias and the Spanish settlements of the Pimería Alta in what is now Arizona and Sonora, they furnished the motive and drive to explore and populate the long California coastline. -

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles The Chinese Navy Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Saunders, EDITED BY Yung, Swaine, PhILLIP C. SAUNderS, ChrISToPher YUNG, and Yang MIChAeL Swaine, ANd ANdreW NIeN-dzU YANG CeNTer For The STUdY oF ChINeSe MilitarY AffairS INSTITUTe For NATIoNAL STrATeGIC STUdIeS NatioNAL deFeNSe UNIverSITY COVER 4 SPINE 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY COVER.indd 3 COVER 1 11/29/11 12:35 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 1 11/29/11 12:37 PM 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 2 11/29/11 12:37 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Edited by Phillip C. Saunders, Christopher D. Yung, Michael Swaine, and Andrew Nien-Dzu Yang Published by National Defense University Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. 2011 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 3 11/29/11 12:37 PM Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Chapter 5 was originally published as an article of the same title in Asian Security 5, no. 2 (2009), 144–169. Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. Used by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Chinese Navy : expanding capabilities, evolving roles / edited by Phillip C. Saunders ... [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Comparison of Spanish Colonization—Latin America and the Philippines

Title: Comparison of Spanish Colonization—Latin America and the Philippines Teacher: Anne Sharkey, Huntley High School Summary: This lesson took part as a comparison of the different aspects of the Spanish maritime empires with a comparison of Spanish colonization of Mexico & Cuba to that of the Philippines. The lessons in this unit begin with a basic understanding of each land based empire of the time period 1450-1750 (Russia, Ottomans, China) and then with a movement to the maritime transoceanic empires (Spain, Portugal, France, Britain). This lesson will come after the students already have been introduced to the Spanish colonial empire and the Spanish trade systems through the Atlantic and Pacific. Through this lesson the students will gain an understanding of Spanish systems of colonial rule and control of the peoples and the territories. The evaluation of causes of actions of the Spanish, reactions to native populations, and consequences of Spanish involvement will be discussed with the direct correlation between the social systems and structures created, the influence of the Christian missionaries, the rebellions and conflicts with native populations between the two locations in the Latin American Spanish colonies and the Philippines. Level: High School Content Area: AP World History, World History, Global Studies Duration: Lesson Objectives: Students will be able to: Compare the economic, political, social, and cultural structures of the Spanish involvement in Latin America with the Spanish involvement with the Philippines Compare the effects of mercantilism on Latin America and the Philippines Evaluate the role of the encomienda and hacienda system on both regions Evaluate the influence of the silver trade on the economies of both regions Analyze the creation of a colonial society through the development of social classes—Peninsulares, creoles, mestizos, mulattos, etc. -

Education Membership of Associations

Prof. Susana Onega Jaén Phone: 34 976 76 15 21 Dpto. de Filología Inglesa y Alemana Fax: 34 976 76 15 19 Facultad de Filosofía y Letras E-mail: [email protected] Universidad de Zaragoza http://cne.literatureresearch.net/ E- 50009 http://filologiainglesa.unizar.es/ Orcid: 0000-0003-1672-4276 EDUCATION Official School of Languages (Madrid): Certificate of Aptitude in French, 1967; Official School of Languages (Madrid): Certificate of Aptitude in English, 1968; The New School of English (Cambridge): Diploma in Advanced English, 1969. University of Heidelberg: Diploma in German Language and Literature (Mittelstufe), 1969; Istituto Italiano di Cultura (Madrid): Diploma in Italian Language and Literature (Primo Umanistico), 1969. University of Cambridge: Certificate of Proficiency in English, 1970; Language Institute, University of Zaragoza: Diploma of Proficiency in German, 1977; University of Zaragoza: Degree in English Philology, 1975 (suma cum laude and extraordinary prize); University of Zaragoza: PhD in English Philology, 1979 (suma cum laude and extraordinary prize). MEMBERSHIP OF ASSOCIATIONS Spanish Association for Anglo-American Studies (AEDEAN), since 1977, Board member (December 1985–December1989), President (December 1990–December 1996); European Association for American Studies (EAAS), since 1977; Instituto de Estudios Ingleses (IEI), founding member, treasurer and secretary, 1985–90. European Society for the Study of Onega: CV 2 English (ESSE), member, since 1990, Spanish Board member, 1990-2000; International Association of University Professors of English (IAUPE), since 1995; National Federation of Associations of Spanish University Professors, 1997-2002; Association of Women Researchers and Technologists (AMIT), since 2003. The English Association, Corresponding Fellow (2003-2006). Member of The Gender Studies Network (within The European Society for the Study of English), since 14 November 2016.