Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Southern Denmark

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN DENMARK THE CHRISTIAN KINGDOM AS AN IMAGE OF THE HEAVENLY KINGDOM ACCORDING TO ST. BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY INSTITUTE OF HISTORY, CULTURE AND CIVILISATION CENTRE FOR MEDIEVAL STUDIES BY EMILIA ŻOCHOWSKA ODENSE FEBRUARY 2010 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In my work, I had the privilege to be guided by three distinguished scholars: Professor Jacek Salij in Warsaw, and Professors Tore Nyberg and Kurt Villads Jensen in Odense. It is a pleasure to admit that this study would never been completed without the generous instruction and guidance of my masters. Professor Salij introduced me to the world of ancient and medieval theology and taught me the rules of scholarly work. Finally, he encouraged me to search for a new research environment where I could develop my skills. I found this environment in Odense, where Professor Nyberg kindly accepted me as his student and shared his vast knowledge with me. Studying with Professor Nyberg has been a great intellectual adventure and a pleasure. Moreover, I never would have been able to work at the University of Southern Denmark if not for my main supervisor, Kurt Villads Jensen, who trusted me and decided to give me the opportunity to study under his kind tutorial, for which I am exceedingly grateful. The trust and inspiration I received from him encouraged me to work and in fact made this study possible. Karen Fogh Rasmussen, the secretary of the Centre of Medieval Studies, had been the good spirit behind my work. -

Downloaded4.0 License

New West Indian Guide 94 (2020) 39–74 nwig brill.com/nwig A Disagreeable Text The Uncovered First Draft of Bryan Edwards’s Preface to The History of the British West Indies, c. 1792 Devin Leigh Department of History, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, USA [email protected] Abstract Bryan Edwards’s The History of the British West Indies is a text well known to histori- ans of the Caribbean and the early modern Atlantic World. First published in 1793, the work is widely considered to be a classic of British Caribbean literature. This article introduces an unpublished first draft of Edwards’s preface to that work. Housed in the archives of the West India Committee in Westminster, England, this preface has never been published or fully analyzed by scholars in print. It offers valuable insight into the production of West Indian history at the end of the eighteenth century. In particular, it shows how colonial planters confronted the challenges of their day by attempting to wrest the practice of writing West Indian history from their critics in Great Britain. Unlike these metropolitan writers, Edwards had lived in the West Indian colonies for many years. He positioned his personal experience as being a primary source of his historical legitimacy. Keywords Bryan Edwards – West Indian history – eighteenth century – slavery – abolition Bryan Edwards’s The History, Civil and Commercial, of the British Colonies in the West Indies is a text well known to scholars of the Caribbean (Edwards 1793). First published in June of 1793, the text was “among the most widely read and influential accounts of the British Caribbean for generations” (V. -

Can Money Whiten? Exploring Race Practice in Colonial Venezuela and Its Implications for Contemporary Race Discourse

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 3 1998 Can Money Whiten? Exploring Race Practice in Colonial Venezuela and Its Implications for Contemporary Race Discourse Estelle T. Lau State University of New York at Buffalo Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Law and Race Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Estelle T. Lau, Can Money Whiten? Exploring Race Practice in Colonial Venezuela and Its Implications for Contemporary Race Discourse, 3 MICH. J. RACE & L. 417 (1998). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol3/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CAN MONEY WHITEN? EXPLORING RACE PRACTICE IN COLONIAL VENEZUELA AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR CONTEMPORARY RACE DISCOURSE Estelle T. Lau* The Gracias al Sacar, a fascinating and seemingly inconceivable practice in eighteenth century colonial Venezuela, allowed certain individuals of mixed Black and White ancestry to purchase "Whiteness" from their King. The author exposes the irony of this system, developed in a society obsessed with "natural" ordering that labeled individuals according to their precise racial ancestry. While recognizing that the Gracias al Sacar provided opportunities for advancement and an avenue for material and social struggle, the author argues that it also justified the persistence of racial hierarchy. -

Than Segregation, Racial Identity: the Neglected Question in Plessy V

Washington and Lee Journal of Civil Rights and Social Justice Volume 10 | Issue 1 Article 3 Spring 4-1-2004 MORE THAN SEGREGATION, RACIAL IDENTITY: THE NEGLECTED QUESTION IN PLESSY V. FERGUSON Thomas J. Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/crsj Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Thomas J. Davis, MORE THAN SEGREGATION, RACIAL IDENTITY: THE NEGLECTED QUESTION IN PLESSY V. FERGUSON, 10 Wash. & Lee Race & Ethnic Anc. L. J. 1 (2004). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/crsj/vol10/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Journal of Civil Rights and Social Justice at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Journal of Civil Rights and Social Justice by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MORE THAN SEGREGATION, RACIAL IDENTITY: THE NEGLECTED QUESTION IN PLESSY V. FERGUSON Thomas J. Davis* I. INTRODUCTION The U.S. Supreme Court's 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson' has long stood as an ignominious marker in U.S. law, symbolizing the nation's highest legal sanction for the physical separation by race of persons in the United States. In ruling against thirty-four-year-old New Orleans shoemaker Homer Adolph Plessy's challenge to Louisiana's Separate Railway Act of 1890,2 the Court majority declared that we think the enforced separation of the races, as applied to the internal commerce of the state, neither abridges the privileges or immunities of the colored man, deprives him of his property without due process of law, nor denies him the equal protection of the laws, within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment.3 One commentator on the Court's treatment of African-American civil rights cast the Plessy decision as "the climactic Supreme Court pronouncement on segregated institutions."4 Historian C. -

The Zacuto Complex: on Reading the Jews in South Africa

Richard Mendelsohn, Milton Shain. The Jews in South Africa: An Illustrated History. Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, 2008. x + 234 pp. $31.95, cloth, ISBN 978-1-86842-281-4. Reviewed by Jonathan Judaken Published on H-Judaic (August, 2009) Commissioned by Jason Kalman (Hebrew Union College - Jewish Institute of Religion) While the frst Jews to officially settle in South hand, Europeans colonized him in the name of Africa did so in the early nineteenth century, the the same basic ideas that justified European ex‐ history of their antecedents is much longer. They pansion and exploitation, notions that we can include Abraham ben Samuel Zacuto, distin‐ name in one word: racism. The "Zacuto complex," guished astronomer and astrologist at the Univer‐ as I want to call it, has played out through most of sity of Salamanca prior to the expulsion of the the history of Jews in South Africa, as this won‐ Jews from Spain in 1492. His astrological tables derful book demonstrates. were published in Hebrew, and then translated The Jews in South Africa, by two of the lead‐ into Latin, and then into Spanish. They were used ing living historians of South Africa’s Jewish past, by Christopher Columbus, and more importantly is the frst general history of South African Jewry by Vasco da Gama, for whom he also selected the in over ffty years. It is written in lively prose, scientific instruments and joined on his voyage to sumptuously illustrated, and includes rare photo‐ Africa.Zacuto, thereby, “was probably the frst Jew graphs as well as documents culled from the ar‐ to land on South African soil when, in mid-No‐ chives, which are inserted into offset “boxes” that vember 1497, the Da Gama party went ashore at help illuminate the forces at work in South St Helena Bay on the Cape west coast” (p. -

Biden Appoints Sociologist to Top Us Science Post

News in focus quite so stark as they are today,” she said. “I believe we have a responsibility to work together to make sure that our science and technology reflects us.” On Biden’s first day as president, his team announced a government-wide effort to pro- mote equity and dismantle structural racism, led by former US ambassador to the United Nations Susan Rice. The team also noted that confronting inequalities and injustice will be central to how the Biden administration tackles climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic. Wide-ranging influence News of Nelson’s leadership role triggered a wave of praise on Twitter from research- ers across disciplines, including computer science, history and American studies. “I think that that outpouring of support is indicative of her impact, and her impact across ALEX WONG/GETTY a whole bunch of different fields,” says Victor Alondra Nelson will help lead the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. Ray, a sociologist who studies race and ethnic- ity at the University of Iowa in Iowa City. The plaudits also acknowledged Nelson’s gener- osity to junior scholars, says Ray — something ‘INSPIRED CHOICE’: BIDEN he experienced when meeting her. She had “a genuine interest in me and my ideas, which APPOINTS SOCIOLOGIST junior scholars really appreciate from some- one of her stature”, he adds. TO TOP US SCIENCE POST Nelson has been president of the Social Science Research Council, a non-profit organ- Scientists praise president’s selection of Alondra ization that supports research in the social sciences, and a professor at the Institute for Nelson, a specialist in bioethics and social inequality. -

Hispanic Minority's Threat to American Identity: Fact Or Fiction

People’s Democratic and Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Larbi Ben M'Hidi University -Oum El Bouaghi- Faculty of Letters and Foreign Languages Department of Letters and English Language Hispanic Minority’s Threat to American Identity: Fact or Fiction A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Master’s Degree in English Literature and Civilization Submitted by: Alligui Amina Bouzid Safia Board of Examiners: Supervisor: Ms. Badi Rima Chairman: Mr. Dalichaouch Abderrahmane Examiner: Ms. Merah Fahima 2019/2020 DEDICATION I dedicate this work: To my beloved mother and my dear father for their love, devotion, and unlimited sacrifice. To my sisters, my brothers, and my friends for their support and encouragement. To my friend Safia, who shared this thesis with me. May Allah bless you all. Amina My successes are because of her and my failures are because of me, to my biggest supporter, to my mother. Also I would like to thank my little family especially my father for his engorgement, patience and assistance over the years, he always kept me in his prayers. To my darling sisters Sarra, Ahlem and Nihal. To my beloved brothers Abdrahmen and Yaakoub. Without forgetting my two angels Zaid and Ayoub Taim Allah. And to my dear colleague Amina, for her continuous support and her beautiful spirit. Safia I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, we thank Allah who gave us the strength and success in writing this work. We would like to thank our supervisor Ms. Badi for her invaluable remarks, as well as her encouragement, enduring support, and wise advice throughout this year. -

New Spain and Early Independent Mexico Manuscripts New Spain Finding Aid Prepared by David M

New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts New Spain Finding aid prepared by David M. Szewczyk. Last updated on January 24, 2011. PACSCL 2010.12.20 New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts Table of Contents Summary Information...................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History.........................................................................................................................................3 Scope and Contents.......................................................................................................................................6 Administrative Information...........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory..................................................................................................................................... 9 - Page 2 - New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts Summary Information Repository PACSCL Title New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts Call number New Spain Date [inclusive] 1519-1855 Extent 5.8 linear feet Language Spanish Cite as: [title and date of item], [Call-number], New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts, 1519-1855, Rosenbach Museum and Library. Biography/History Dr. Rosenbach and the Rosenbach Museum and Library During the first half of this century, Dr. Abraham S. W. Rosenbach reigned supreme as our nations greatest bookseller. -

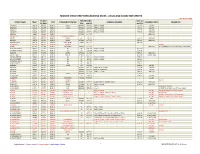

Residential Resurfacing List

MISSION VIEJO STREET RESURFACING INDEX - LOCAL AND COLLECTOR STREETS Rev. DEC 31, 2020 TB MAP RESURFACING LAST AC STREET NAME TRACT TYPE COMMUNITY/OWNER ADDRESS NUMBERS PAVEMENT INFO COMMENTS PG GRID TYPE MO/YR MO/YR ABADEJO 09019 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 28241 to 27881 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABADEJO 09018 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 27762 to 27832 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABANICO 09566 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27551 to 27581 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABANICO 09568 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27541 to 27421 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABEDUL 09563 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 .35AC/NS ABERDEEN 12395 922 C7 PRIVATE HIGHLAND CONDOS -- ABETO 08732 892 D5 PUBLIC MVEA AC JUL 15 JUL 15 .35AC/NS ABRAZO 09576 892 D3 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ACACIA COURT 08570 891 J6 PUBLIC TIMBERLINE TRMSS OCT 14 AUG 08 ACAPULCO 12630 892 F1 PRIVATE PALMIA -- GATED ACERO 79-142 892 A6 PUBLIC HIGHPARK TRMSS OCT 14 .55AC/NS 4/1/17 TRMSS 40' S of MAQUINA to ALAMBRE ACROPOLIS DRIVE 06667 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24582 to 24781 AUG 08 ACROPOLIS DRIVE 07675 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24801 to 24861 AUG 08 ADELITA 09078 892 D4 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ADOBE LANE 06325 922 C1 PUBLIC MVSRC RPMSS OCT 17 AUG 08 .17SAC/.58AB ADONIS STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24161 to 24232 SEP 14 ADONIS STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24101 to 24152 SEP 14 ADRIANA STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AEGEA STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AGRADO 09025 922 D1 PUBLIC OVGA AC AUG 18 AUG 18 .4AC/NS AGUILAR 09255 892 D1 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 PINAVETE -

Deborah Gochfield

DEBORAH JEAN GOCHFELD National Center for Natural Products Research P.O. Box 1848, University of Mississippi University, MS 38677-1848 Phone (662) 915-6769; Home (662) 281-0313 Fax: (662) 915-7062; Email: [email protected] EDUCATION: Ph.D. Zoology, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii. Dec. 1997. Dissertation title: Mechanisms of coexistence between corals and coral-feeding butterflyfishes: territoriality, foraging behavior, and prey defense. B.A. Biology, Phi Beta Kappa, Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, New York. May 1988. RESEARCH EXPERIENCE: Senior Scientist, National Center for Natural Products Research, University of Mississippi, Oxford, MS. July 2006-present. Diseases of coral reef organisms. Chemical ecology of marine invertebrates. Phenotypic plasticity in chemical defenses of corals and sponges, particularly as they relate to pathogens and predators. Use of chemical ecology to direct drug discovery efforts from marine resources of Caribbean and Indo-Pacific reefs. Visiting Scientist, Caribbean Coral Reef Ecosystem Program, Smithsonian Marine Science Network. 2008-present. Prevalence and virulence of sponge diseases in the Caribbean. Visiting Scientist, Caribbean Marine Research Center, Lee Stocking Island, Bahamas. 2000-present. Chemical ecology, physiology and microbiology of corals and sponges as related to disease and other environmental stressors. Behavioral ecology of sponge- and coral-feeding fishes. Pheromones as signals for sex change in a marine goby. Antimicrobial and antipredator natural products from cave and reef sponges. Research Scientist, National Center for Natural Products Research and Ocean Biotechnology Center and Repository of the National Institute of Undersea Science and Technology, University of Mississippi, Oxford, MS. Sept. 2001-June 2006. Chemical ecology of marine invertebrates. Phenotypic plasticity in chemical defenses of corals, particularly as they relate to coral pathogens and predators. -

Early Mexican American Literature and the Production of Transnational Counterspaces, 1885-1958 Diana Noreen Rivera

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository English Language and Literature ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 9-12-2014 Remapping the U.S. "Southwest": Early Mexican American Literature and the Production of Transnational Counterspaces, 1885-1958 Diana Noreen Rivera Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/engl_etds Recommended Citation Rivera, Diana Noreen. "Remapping the U.S. "Southwest": Early Mexican American Literature and the Production of Transnational Counterspaces, 1885-1958." (2014). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/engl_etds/30 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Language and Literature ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Díana Noreen Rivera Candidate English Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jesse Alemán, Chairperson Dr. María Cotera Dr. Kathleen Washburn Dr. Emilio Zamora ii REMAPPING THE U.S. “SOUTHWEST”: EARLY MEXICAN AMERICAN LITERATURE AND THE PRODUCTION OF TRANSNATIONAL COUNTERSPACES, 1885-1958 By DÍANA NOREEN RIVERA B.A., English, University of Texas Pan American, 2003 M.A., English, University of Texas Pan American, 2005 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy English The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July, 2014 iii ©2014, Díana Noreen Rivera iv Dedication To my mother and father Whose never-ending love, encouragement and wisdom Guides me, always To Sam Whose partnership, support and love Fulfills me on this journey through life To the memory of my grandmothers And todo mi familia Who have crisscrossed Borders, nations, oceans, and towns And shared with me their stories. -

From African to African American: the Creolization of African Culture

From African to African American: The Creolization of African Culture Melvin A. Obey Community Services So long So far away Is Africa Not even memories alive Save those that songs Beat back into the blood... Beat out of blood with words sad-sung In strange un-Negro tongue So long So far away Is Africa -Langston Hughes, Free in a White Society INTRODUCTION When I started working in HISD’s Community Services my first assignment was working with inner city students that came to us straight from TYC (Texas Youth Commission). Many of these young secondary students had committed serious crimes, but at that time they were not treated as adults in the courts. Teaching these young students was a rewarding and enriching experience. You really had to be up close and personal with these students when dealing with emotional problems that would arise each day. Problems of anguish, sadness, low self-esteem, disappointment, loneliness, and of not being wanted or loved, were always present. The teacher had to administer to all of these needs, and in so doing got to know and understand the students. Each personality had to be addressed individually. Many of these students came from one parent homes, where the parent had to work and the student went unsupervised most of the time. In many instances, students were the victims of circumstances beyond their control, the problems of their homes and communities spilled over into academics. The teachers have to do all they can to advise and console, without getting involved to the extent that they lose their effectiveness.