Art and Politics in China, 1949-1986

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Chen Qiulin), 25F a Cheng, 94F a Xian, 276 a Zhen, 142F Abso

Index Note: “f ” with a page number indicates a figure. Anti–Spiritual Pollution Campaign, 81, 101, 102, 132, 271 Apartment (gongyu), 270 “......” (Chen Qiulin), 25f Apartment art, 7–10, 18, 269–271, 284, 305, 358 ending of, 276, 308 A Cheng, 94f internationalization of, 308 A Xian, 276 legacy of the guannian artists in, 29 A Zhen, 142f named by Gao Minglu, 7, 269–270 Absolute Principle (Shu Qun), 171, 172f, 197 in 1980s, 4–5, 271, 273 Absolution Series (Lei Hong), 349f privacy and, 7, 276, 308 Abstract art (chouxiang yishu), 10, 20–21, 81, 271, 311 space of, 305 Abstract expressionism, 22 temporary nature of, 305 “Academic Exchange Exhibition for Nationwide Young women’s art and, 24 Artists,” 145, 146f Apolitical art, 10, 66, 79–81, 90 Academicism, 78–84, 122, 202. See also New academicism Appearance of Cross Series (Ding Yi), 317f Academic realism, 54, 66–67 Apple and thinker metaphor, 175–176, 178, 180–182 Academic socialist realism, 54, 55 April Fifth Tian’anmen Demonstration (Li Xiaobin), 76f Adagio in the Opening of Second Movement, Symphony No. 5 April Photo Society, 75–76 (Wang Qiang), 108f exhibition, 74f, 75 Adam and Eve (Meng Luding), 28 Architectural models, 20 Aestheticism, 2, 6, 10–11, 37, 42, 80, 122, 200 Architectural preservation, 21 opposition to, 202, 204 Architectural sites, ritualized space in, 11–12, 14 Aesthetic principles, Chinese, 311 Art and Language group, 199 Aesthetic theory, traditional, 201–202 Art education system, 78–79, 85, 102, 105, 380n24 After Calamity (Yang Yushu), 91f Art field (yishuchang), 125 Agree -

New China's Forgotten Cinema, 1949–1966

NEW CHINA’S FORGOTTEN CINEMA, 1949–1966 More Than Just Politics by Greg Lewis Several years ago when planning a course on modern Chinese history as seen through its cinema, I realized or saw a significant void. I hoped to represent each era of Chinese cinema from the Leftist movement of the 1930s to the present “Sixth Generation,” but found most available subtitled films are from the post-1978 reform period. Films from the Mao Zedong period (1949–76) are particularly scarce in the West due to Cold War politics, including a trade embargo and economic blockade lasting more than two decades, and within the arts, a resistance in the West to Soviet- influenced Socialist Realism. wo years ago I began a project, Translating New China’s Cine- Phase One. Economic Recovery, ma for English-Speaking Audiences, to bring Maoist Heroic Revolutionaries, and Workers, T cinema to students and educators in the US. Several genres Peasants, and Soldiers (1949–52) from this era’s cinema are represented in the fifteen films we have Despite differences in perspective on Maoist cinema, general agree- subtitled to date, including those of heroic revolutionaries (geming ment exists as to the demarcation of its five distinctive phases (four yingxiong), workers-peasants-soldiers (gongnongbing), minority of which are represented in our program). The initial phase of eco- peoples (shaoshu minzu), thrillers (jingxian), a children’s film, and nomic recovery (1949–52) began with the emergence of the Dong- several love stories. Collectively, these films may surprise teachers bei (later Changchun) Film Studio as China’s new film capital. -

Joan Lebold Cohen Interview Transcript

www.china1980s.org INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT JOAN LEBOLD COHEN Interviewer: Jane DeBevoise Date:31 Oct 2009 Duration: about 2 hours Location: New York Jane DeBevoise (JD): It would be great if you could speak a little bit about how you got to China, when you got to China – with dates specific to the ‘80s, and how you saw the 80’s develop. From your perspective what were some of the key moments in terms of the arts? Joan Lebold Cohen (JC): First of all, I should say that I had been to China three times before the 1980s. I went twice in 1972, once on a delegation in May for over three weeks, which took us to Beijing, Luoyang, Xi’an, and Shanghai and we flew into Nanchang too because there were clouds over Guangzhou and the planes couldn’t fly in. This was a period when, if you wanted to have a meal and you were flying, the airplane would land so that you could go to a restaurant (Laughter). They were old, Russian airplanes, and you sat in folding chairs. The conditions were rather…primitive. But I remember going down to the Shanghai airport and having the most delicious ‘8-precious’ pudding and sweet buns – they were fantastic. I also went to China in 1978. For each trip, I had requested to meet artists and to go to exhibitions, but was denied the privilege. However, there was one time, when I went to an exhibition in May of 1972 and it was one of the only exhibitions that exhibited Cultural Revolution model paintings; it was very amusing. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

P020110307527551165137.Pdf

CONTENT 1.MESSAGE FROM DIRECTOR …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 03 2.ORGANIZATION STRUCTURE …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 05 3.HIGHLIGHTS OF ACHIEVEMENTS …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 Coexistence of Conserve and Research----“The Germplasm Bank of Wild Species ” services biodiversity protection and socio-economic development ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 The Structure, Activity and New Drug Pre-Clinical Research of Monoterpene Indole Alkaloids ………………………………………… 09 Anti-Cancer Constituents in the Herb Medicine-Shengma (Cimicifuga L) ……………………………………………………………………………… 10 Floristic Study on the Seed Plants of Yaoshan Mountain in Northeast Yunnan …………………………………………………………………… 11 Higher Fungi Resources and Chemical Composition in Alpine and Sub-alpine Regions in Southwest China ……………………… 12 Research Progress on Natural Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV) Inhibitors…………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Predicting Global Change through Reconstruction Research of Paleoclimate………………………………………………………………………… 14 Chemical Composition of a traditional Chinese medicine-Swertia mileensis……………………………………………………………………………… 15 Mountain Ecosystem Research has Made New Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Plant Cyclic Peptide has Made Important Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 17 Progresses in Computational Chemistry Research ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 18 New Progress in the Total Synthesis of Natural Products ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… -

Cultural Significance and Artistic Value of Chinese Folk New Year Pictures in Traditional Festivals

2019 International Conference on Humanities, Cultures, Arts and Design (ICHCAD 2019) Cultural Significance and Artistic Value of Chinese Folk New Year Pictures in Traditional Festivals Zhiqiang Chena,*, Yongding Tanb Lingnan Normal University, Zhanjiang, 750021, China [email protected], [email protected] *Corresponding Author Keywords: New Year Pictures, Cultural Significance, Artistic Value Abstract: the History of Chinese Folk New Year Pictures Can Be Traced Back to the Han Dynasty. It Occupies an Important Position in People's Spiritual and Cultural Life and is a Valuable Cultural Heritage of the Chinese Nation. in the Long Process of Development, Chinese Traditional Folk New Year Paintings Have Formed a Unique Painting Style. Its Composition, Shape, Colour and Other Factors Have Strong Subjective Imagery, Reflecting People's Cognitive Concepts. New Year Pictures Express the Basic Spirit of Chinese Traditional Culture with the Cultural Form Closest to People and Life, Providing a Unique Spiritual Temperament for the Survival and Continuation of the Nation and Culture. It is a Popular Reading Material and Educational Reading Material for the People and Plays a Role in Popularizing Historical Knowledge and Moral Education. New Year Pictures Have Beautiful Shapes and Colours, Which Promote the Formation of People's Aesthetics, Spread Aesthetic Ideas and Form Their Own Unique Views on Shapes and Colours. 1. Introduction The Chinese culture and art have a long history, stretching from ancient times to modern times. The vast expanse of water is unbridled and brilliant, shining in the sky of world civilization. Chinese folk wood engraving New Year pictures have a long history and cover a wide range of areas in our country. -

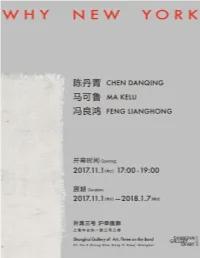

WHY-NEW-YORK-Artworks-List.Pdf

“Why New York” 是陈丹青、马可鲁、冯良鸿三人组合的第四次展览。这三位在中国当代艺术的不同阶 段各领风骚的画家在1990年代的纽约聚首,在曼哈顿和布鲁克林既丰饶又严酷的环境中白手起家,互 相温暖呵护,切磋技艺。到了新世纪,三人不约而同地回到中国,他们不忘艺术的初心,以难忘的纽约 岁月为缘由,频频举办联展。他们的组合是出于情谊,是在相互对照和印证中发现和发展各自的面目, 也是对艺术本心的坚守和砥砺。 不同于前几次带有回顾性的展览,这一次三位艺术家呈现了他们阶段性的新作。陈丹青带来了对毕加 索等西方艺术家以及中国山水及书法的研究,他呈现“画册”的绘画颇具观念性,背后有复杂的摹写、转 译、造型信息与图像意义的更替演化等话题。马可鲁的《Ada》系列在“无意识”中蕴含着规律,呈现出 书写性,在超越表面的技巧和情感因素的画面中触及“真实的自然”。冯良鸿呈现了2012年以来不同的 几种方向,在纯色色域的覆盖与黑白意境的推敲中展现视觉空间的质感。 在为展览撰写的文章中,陈丹青讲述了在归国十余年后三人作品中留有的纽约印记。这三位出生于上海 的画家此次回归家乡,又一次的聚首凝聚了岁月的光华,也映照着他们努力前行的年轻姿态。 “Why New York” marks the fourth exhibition of the artists trio, Chen Danqing, Ma Kelu and Feng Lianghong. Being the forerunners at the various stages in the progress of Chinese contemporary art, these artists first met in New York in the 1990s. In that culturally rich yet unrelenting environment of Manhattan and Brooklyn, they single-handedly launched their artistic practice, provided camaraderie to each other and exchanged ideas about art. In the new millennium, they’ve returned to China respectively. Bearing in mind their artistic ideals, their friendship and experiences of New York reunite them to hold frequent exhibitions together. With this collaboration built on friendship, they continue to discover and develop one’s own potential through the mirror of the others, as they persevere and temper in reaching their ideals in art. Unlike the previous retrospective exhibitions, the artists present their most recent works. Chen Danqing’s study on Picasso and other Western artists along with Chinese landscape painting and calligraphy is revealed in his conceptual painting “Catalogue”, a work that addresses the complex notions of drawing, translation, compositional lexicon and pictorial transformation. Ma Kelu’s “Ada” series embodies a principle of the “unconscious”, whose cursive and hyper expressive techniques adroitly integrates with the emotional elements of the painting to render “true nature”. -

Lucky Motifs in Chinese Folk Art: Interpreting Paper-Cut from Chinese Shaanxi

Asian Studies I (XVII), 2 (2013), pp. 123–141 Lucky Motifs in Chinese Folk Art: Interpreting Paper-cut from Chinese Shaanxi Xuxiao WANG Abstract Paper-cut is not simply a form of traditional Chinese folk art. Lucky motifs developed in paper-cut certainly acquired profound cultural connotations. As paper-cut is a time- honoured skill across the nation, interpreting those motifs requires cultural receptiveness and anthropological sensitivity. The author of this article analyzes examples of paper-cut from Northern Shaanxi, China, to identify the cohesive motifs and explore the auspiciousness of the specific concepts of Fu, Lu, Shou, Xi. The paper-cut of Northern Shaanxi is an ideal representative of the craft as a whole because of the relative stability of this region in history, in terms of both art and culture. Furthermore, its straightforward style provides a clear demonstration of motifs regarding folk understanding of expectations for life. Keywords: Paper-cut, Shaanxi, lucky motifs, cultural heritage Izvleček Izrezljanka iz papirja ni le ena izmed oblik tradicionalne kitajske ljudske umetnosti, saj določeni motivi sreče, ki so se razvili znotraj te umetnosti, zahtevajo poglobljeno razumevanje kulturnih konotacij. Ker je izrezljanka iz papirja častitljiva in stara veščina, ki se izdeluje po vsej državi, je za interpretacijo teh motivov potrebna kulturna receptivnost in antropološka senzitivnost. Avtorica pričujočega članka analizira primere izrezljank iz papirja iz severnega dela province Shaanxi na Kitajskem, da bi identificirala povezane motive ter raziskala dojemanje sreče in ugodnosti specifičnih konceptov, kot so Fu, Lu, Shou, Xi. Zaradi relativne stabilnosti severnega dela province Shaanxi v zgodovini, tako na področju umetnosti kot kulture, so izrezljanke iz papirja iz tega območja vzoren predstavnik rokodelstva kot celote. -

Final Program of CCC2020

第三十九届中国控制会议 The 39th Chinese Control Conference 程序册 Final Program 主办单位 中国自动化学会控制理论专业委员会 中国自动化学会 中国系统工程学会 承办单位 东北大学 CCC2020 Sponsoring Organizations Technical Committee on Control Theory, Chinese Association of Automation Chinese Association of Automation Systems Engineering Society of China Northeastern University, China 2020 年 7 月 27-29 日,中国·沈阳 July 27-29, 2020, Shenyang, China Proceedings of CCC2020 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP2040A -USB ISBN: 978-988-15639-9-6 CCC2020 Copyright and Reprint Permission: This material is permitted for personal use. For any other copying, reprint, republication or redistribution permission, please contact TCCT Secretariat, No. 55 Zhongguancun East Road, Beijing 100190, P. R. China. All rights reserved. Copyright@2020 by TCCT. 目录 (Contents) 目录 (Contents) ................................................................................................................................................... i 欢迎辞 (Welcome Address) ................................................................................................................................1 组织机构 (Conference Committees) ...................................................................................................................4 重要信息 (Important Information) ....................................................................................................................11 口头报告与张贴报告要求 (Instruction for Oral and Poster Presentations) .....................................................12 大会报告 (Plenary Lectures).............................................................................................................................14 -

Independent Cinema in the Chinese Film Industry

Independent cinema in the Chinese film industry Tingting Song A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology 2010 Abstract Chinese independent cinema has developed for more than twenty years. Two sorts of independent cinema exist in China. One is underground cinema, which is produced without official approvals and cannot be circulated in China, and the other are the films which are legally produced by small private film companies and circulated in the domestic film market. This sort of ‘within-system’ independent cinema has played a significant role in the development of Chinese cinema in terms of culture, economics and ideology. In contrast to the amount of comment on underground filmmaking in China, the significance of ‘within-system’ independent cinema has been underestimated by most scholars. This thesis is a study of how political management has determined the development of Chinese independent cinema and how Chinese independent cinema has developed during its various historical trajectories. This study takes media economics as the research approach, and its major methods utilise archive analysis and interviews. The thesis begins with a general review of the definition and business of American independent cinema. Then, after a literature review of Chinese independent cinema, it identifies significant gaps in previous studies and reviews issues of traditional definition and suggests a new definition. i After several case studies on the changes in the most famous Chinese directors’ careers, the thesis shows that state studios and private film companies are two essential domestic backers for filmmaking in China. -

UC Berkeley Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review

UC Berkeley Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review Title "Music for a National Defense": Making Martial Music during the Anti-Japanese War Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7209v5n2 Journal Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review, 1(13) ISSN 2158-9674 Author Howard, Joshua H. Publication Date 2014-12-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California “Music for a National Defense”: Making Martial Music during the Anti-Japanese War Joshua H. Howard, University of Mississippi Abstract This article examines the popularization of “mass songs” among Chinese Communist troops during the Anti-Japanese War by highlighting the urban origins of the National Salvation Song Movement and the key role it played in bringing songs to the war front. The diffusion of a new genre of march songs pioneered by Nie Er was facilitated by compositional devices that reinforced the ideological message of the lyrics, and by the National Salvation Song Movement. By the mid-1930s, this grassroots movement, led by Liu Liangmo, converged with the tail end of the proletarian arts movement that sought to popularize mass art and create a “music for national defense.” Once the war broke out, both Nationalists and Communists provided organizational support for the song movement by sponsoring war zone service corps and mobile theatrical troupes that served as conduits for musicians to propagate their art in the hinterland. By the late 1930s, as the United Front unraveled, a majority of musicians involved in the National Salvation Song Movement moved to the Communist base areas. Their work for the New Fourth Route and Eighth Route Armies, along with Communist propaganda organizations, enabled their songs to spread throughout the ranks. -

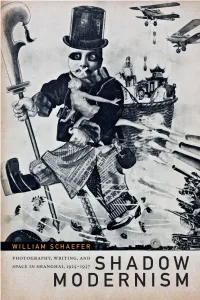

Read the Introduction

William Schaefer PhotograPhy, Writing, and SPace in Shanghai, 1925–1937 Duke University Press Durham and London 2017 © 2017 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Text designed by Mindy Basinger Hill Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Schaefer, William, author. Title: Shadow modernism : photography, writing, and space in Shanghai, 1925–1937 / William Schaefer. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and ciP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017007583 (print) lccn 2017011500 (ebook) iSbn 9780822372523 (ebook) iSbn 9780822368939 (hardcover : alk. paper) iSbn 9780822369196 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcSh: Photography—China—Shanghai—History—20th century. | Modernism (Art)—China—Shanghai. | Shanghai (China)— Civilization—20th century. Classification: lcc tr102.S43 (ebook) | lcc tr102.S43 S33 2017 (print) | ddc 770.951/132—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007583 Cover art: Biaozhun Zhongguoren [A standard Chinese man], Shidai manhua (1936). Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University Libraries. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of the University of Rochester, Department of Modern Languages and Cultures and the College of Arts, Sciences, and Engineering, which provided funds toward the publication