Post-War State-Making in the Angolan Periphery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Angola's New President

Angola’s new president Reforming to survive Paula Cristina Roque President João Lourenço – who replaced José Eduardo dos Santos in 2017 – has been credited with significant progress in fighting corruption and opening up the political space in Angola. But this has been achieved against a backdrop of economic decline and deepening poverty. Lourenço’s first two years in office are also characterised by the politicisation of the security apparatus, which holds significant risks for the country. SOUTHERN AFRICA REPORT 38 | APRIL 2020 Key findings The anti-corruption drive is not transparent While fear was endemic among the people and President João Lourenço is accused of under Dos Santos, there is now ‘fear among targeting political opponents and protecting the elites’ due to the perceived politicised those who support him. anti-corruption drive. Despite this targeted approach, there is an Economic restructuring is leading to austerity attempt by the new president to reform the measures and social tension – the greatest risk economy and improve governance. to Lourenço’s government. After decades of political interference by The greatest challenge going forward is reducing the Dos Santos regime, the fight against poverty and reviving the economy. corruption would need a complete overhaul of Opposition parties and civil society credit the judiciary and public institutions. Lourenço with freeing up the political space The appointment of a new army chief led and media. to the deterioration and politicisation of the Angolan Armed Forces. Recommendations For the president and the Angolan government: Use surplus troops and military units to begin setting up cooperative farming arrangements Urgently define, fund and implement an action with diverse communities, helping establish plan to alleviate the effects of the recession on irrigation systems with manual labour. -

Eliana Miss Angola Em Portugal

Jornal Bimestral de Actualidade Angolana SETEMBRO | OUTUBRO 2009 EDIÇÃO GRATUITA www.embaixadadeangola.org EDIÇÃO DOS SERVIÇOS DE IMPRENSA DA EMBAIXADA DE ANGOLA EM PORTUGAL ELIANA MISS ANGOLA EM PORTUGAL Pág. 16 EMBAIXADOR STÉLVIO COMENTA PATRIÓTICO! RELAÇÕES COM PORTUGAL Pág. 14 FESTA DOS FAMOSOS EM LISBOA Pág. 11 ASSUNÇÃO DOS ANJOS DISCURSA NA ONU Pág. 3 Pág. 2 2 Política SETEMBRO • OUTUBRO 2009 NA 64ª SESSÃO DA AG DA ONU ASSUNÇÃO DOS ANJOS PEDE CONCLUSÃO DAS REFORMAS Governo angolano apelou à con- igualmente, factores de extrema im- desarmamento, a persistência dos con- ca, o desenvolvimento e o progresso O clusão das negociações iniciadas portância que requerem permanente- flitos armados e as suas consequências do continente. O ministro sublinhou em 2005, tendo em vista a reforma mente a atenção das Nações Unidas, na vida das populações, a fome e a que Angola acredita ser possível re- do Conselho de Segurança das Na- reclamando maior eficácia nas medi- pobreza, as doenças endémicas, como duzir, substancialmente, o défice da ções Unidas, particularmente no que das a adoptar e um maior engaja- a malária e a tuberculose, que provo- segurança alimentar em África se a diz respeito à sua composição e de- mento da comunidade Internacional”, cam milhões de mortes por ano, e, em comunidade internacional se congre- mocratização do seu mecanismo de frisou. Assunção dos Anjos apontou África, devastam toda uma geração, gar em torno de eixos fundamentais, tomada de decisões. O apelo foi feito outros desafios, como as questões do pondo em causa, de forma dramáti- como a manutenção das reservas pelo ministro das Relações Exteriores, mínimas de alimentos e medicamen- Assunção dos Anjos, quando discursa- tos para as ajudas de emergência e va, em Nova Iorque, na 64ª sessão da humanitárias às populações carentes. -

2007 Outubro 06-13 Imperícia, Falta De Independência Do Judiciário Ou Parcialidade? Três Actos Da Trama Que Condenou Graça Campos

2007 Outubro 06-13 Imperícia, falta de independência do judiciário ou parcialidade? Três actos da trama que condenou Graça Campos O julgamento que condenou Graça Campos a oito meses de prisão efectiva e ao pagamento de uma indemnização de 250 mil dólares a Paulo Tjipilica foi feito à revelia, decorrendo na sua ausência e também na dos seus representantes legais. A 25 de Agosto último, quando o juiz Pedro Viana reuniu o tribunal para deliberar a acção em que o Provedor de Justiça pedia que Graça Campos fosse condenado e reparasse alegados crimes de injúria e difamação por via de uma indemnização, o jornalista não se encontrava em Angola. Os seus advogados, João Gourgel e Paulo Rangel, não estavam avisados da ocorrência do julgamento e também não compareceram ao tribunal. Quando, regressado ao país, o jornalista se apercebeu do desenrolar dos acontecimentos, accionou os serviços dos seus advogados, que se apressaram a justificar as faltas e solicitaram a realização de novo julgamento, tudo isso de acordo com aquilo que a lei prevê para situações do género. Os advogados justificaram a falta com «dificuldades com as notificações e ausência do país do seu constituinte». Com isso, a defesa pretendia esclarecer plenamente os factos em resposta às petições de Paulo Tjipilica e permitir que fossem produzidas as provas que possibilitassem que fosse feita justiça. Mas o juiz Paulo Viana indeferiu essa petição dos advogados, dando prosseguimento à acção no quadro das precárias «démarches» já encetadas. Segundo informações disponíveis, quando Graça Campos estava ausente de Angola e não pôde zelar pela sua defesa e muito menos fazer-se presente para julgamento, Pedro Viana escreveu â Ordem dos Advogados de Angola (Oaa) solicitando defesa oficiosa. -

Angola: Parallel Governments, Oil and Neopatrimonial System Reproduction

Institute for Security Studies Situation Report Date issued: 6 June 2011 Author: Paula Cristina Roque* Distribution: General Contact: [email protected] Angola: Parallel governments, oil and neopatrimonial system reproduction Introduction Over the last 35 years, the central government in Luanda has not only survived a potent insurgency, external intervention, international isolation, sanctions and economic collapse, but it has also managed to emerge victorious from a highly destructive and divisive civil war, achieving double-digit economic growth less than a decade after the cessation of hostilities. Hence the state in Angola may be regarded as resilient and even effective. However, closer examination of the Angolan political order reveals a very distinct reality of two parallel ruling structures: the formal, fragile government ruled by the Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA) and the more resilient ‘shadow’ government controlled and manipulated by the presidency, with Sonangol, the national oil company, as its chief economic motor. While these structures are mutually dependent, their internal functions are sometimes at odds with each other. Recent changes to these structures reveal the faultlines the ruling elite has tried to conceal, as well as new opportunities for engagement with the ruling structures of Angola by African and international policymakers. The Angolan The Angolan state displays several aspects of failure and resilience that, in its oil state: Two hybrid configuration, combines formal and informal operating procedures, is governments highly adaptable and able to survive great difficulties. Reforms in Angola are between more a reflection of the need to adapt to change as a means to maintain control democracy of the state – and to control the rate at which any change occurs – than a genuine and hegemony opening of the political space to ideas of good governance, let alone popular (2008–2010) accountability. -

Angola Achieves Output Record with Greater Plutonio Startup

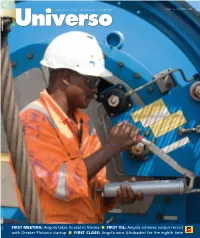

SONANGOL ANGOLA | OIL | BUSINESS | CULTURE ISSUE 16 WINTER 2007 UNIVERSO Universo ISSUE 16 – WINTER 2007 FIRST MEETING: Angola takes its seat in Vienna ■ FIRST OIL: Angola achieves output record with Greater Plutonio startup ■ FIRST CLASS: Angola wins Afrobasket for the eighth time ISSUE 16 WINTER 2007 INSIDE SONANGOL INSIDE ANGOLA Moving On 8. Turned On 32. Weekend Away The amazing changes that have Eight years after the initial discovery on With every year that passes since the materialised in Angola Block 18, first oil flows from the Greater end of hostilities in 2003, the possibil- during the four years Plutonio field bringing Angola’s production ities for tourism offered by Angola’s that Universo has goal of 2 million barrels per day a signifi- welcoming coast and countryside been published seem TENTS cant step closer become increasingly evident scarcely credible. In 2004, the coun- try was little known except as a war zone. Now it is one of Africa’s major oil pro- ducers, set to achieve CON the coveted daily production level of 2 million 38. The Hungry bpd in the new year. In September Angola took Dragon its seat in Vienna as member of the exclusive Opec club – and in another demonstration of China’s rising profile on the the country’s coming of age as an oil state, 12. In the Big League Now African continent, particularly in Luanda was recently the setting for the 2nd Angola, offers important oppor- Admission to Opec has put Angola on the front line of Deepwater Offshore West Africa Conference, tunities as well as challenges for global petropolitics, so Universo joined the international attended by leading oil engineers, scientists the countries involved media corps to catch the tension and drama in Vienna and other industry leaders from all over the world. -

Angola Country Report

ANGOLA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Angola October 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of the document 1.1 2. Geography 2.1 3. Economy 3.1 4. History Post-Independence background since 1975 4.1 Multi-party politics and the 1992 Elections 4.2 Lusaka Peace Accord 4.6 Political Situation and Developments in the Civil War September 1999 - February 4.13 2002 End of the Civil War and Political Situation since February 2002 4.19 5. State Structures The Constitution 5.1 Citizenship and Nationality 5.4 Political System 5.9 Presidential and Legislative Election Plans 5.14 Judiciary 5.19 Court Structure 5.20 Traditional Courts 5.23 UNITA - Operated Courts 5.24 The Effect of the Civil War on the Judiciary 5.25 Corruption in the Judicial System 5.28 Legal Documents 5.30 Legal Rights/Detention 5.31 Death Penalty 5.38 Internal Security 5.39 Angolan National Police (ANP) 5.40 Armed Forces of Angola (Forças Armadas de Angola, FAA) 5.43 Prison and Prison Conditions 5.45 Military Service 5.49 Forced Conscription 5.52 Draft Evasion and Desertion 5.54 Child Soldiers 5.56 Medical Services 5.59 HIV/AIDS 5.67 Angola October 2004 People with Disabilities 5.72 Mental Health Treatment 5.81 Educational System 5.82 6. Human Rights 6.A Human Rights Issues General 6.1 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.5 Newspapers 6.10 Radio and Television 6.13 Journalists 6.18 Freedom of Religion 6.25 Religious Groups 6.28 Freedom of Association and Assembly 6.29 Political Activists – UNITA 6.43 -

The Clinton Administration Has Failed to Recognize and Shore up the Newly-Elected Multiparty Government

THE WASHINGTON OFFICE ON AFRICA 110 M ARYLA ND A VENUE , N . E . WASH I NGTON , D .C. 20002 PHONE (202 ) 546 - 7 96 1 FA X ( 202 ) 546- 1545 February 10, 1993 Dear Friend, The situation in Angola is dire. Having lost the September elections, Jonas Savimbi and his UNITA (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola) forces plunged the country back into full-scale war. As a result of UNIT A's latest round of attacks, over 16,000 people have been killed, thousands have fled UNITA-held areas, and over 1.4 million people currently face starvation. For almost two weeks now, UNITA has cut off the water supply to Luanda, the capital. On 31 January 1993, the United Nations extended its mandate in Angola until April. However, the UN is considering a scale-down of its already modest force to below 100, which would leave Angolans at the mercy of UNIT A forces currently poised to take military control over the country. UNIT A has already seized 75 percent of the country, including much of the northern oil and diamond rich areas which has placed a stranglehold on the Angolan economy. As indicated in the enclosed articles, UNIT A's current military offensive is being heavily assisted by South Africans and Zairians as well as white mercenaries. The Frontline States called an emergency meeting in December to protest South African destabilization tactics, and Namibian authorities recently seized three South African planes attempting to ferry supplies to UNIT A from the northern Namibian town of Rundu. -

2008 Higino Carneiro Anuncia Reposição De Mil E 500 Pontes Até

2008 Higino Carneiro anuncia reposição de mil e 500 pontes até 2012 Angop O ministro das Obras Públicas, Higino Carneiro, anunciou hoje (quinta-feira), em Luanda, a intenção do Governo Angolano construir ou reconstruir cerca de mil e 500 pontes de médio e grande porte, assim como reabilitar mais de 12 mil quilómetros da rede nacional de estradas até 2012. Falando na sessão de abertura do II Congresso Africano de Estradas, que decorre de 26 a 28 deste mês no Centro de Convenções Talatona, o governante sublinhou que o governo, sob direcção do Presidente da República, José Eduardo dos Santos, tem vindo a desenvolver um amplo programa de reconstrução nacional de infra-estruturas rodoviárias. Segundo disse, o Instituto de Estradas de Angola (INEA) está a promover agora a actualização dos estatutos das estradas nacionais e o plano rodoviário nacional. Acrescentou que a instituição está ainda a fixar um plano director de passagem para controlo das cargas dos veículos em circulação e a concluir um novo manual de sinalização, a fim de compatibilizar-se com as normas da Comunidade dos Países da África Austral (SADC). Segundo afirmou, os resultados até hoje alcançados ilustram bem os esforços realizados, os benefícios obtidos e a satisfação que os cidadãos expressam pelas mudanças visíveis na circulação de pessoas e bens. “ Esta verdade é indesmentível, traduz-se hoje num elemento facilitador para organização e realização das eleições legislativas que terão lugar a 5 de Setembro de 2008 ”, referiu o ministro das Obras Públicas. Na sua óptica, a estabilidade política, a estabilização macro-económica, o desenvolvimento dos actores públicos e privados nos diferentes sectores da economia asseguram o crescimento económico que o país vem registando. -

20111011 Corruption in Angola

Corruption in Angola: An Impediment to Democracy Rafael Marques de Morais* * The author is currently writing a book on corruption in Angola. He has recently published a book on human rights abuses and corruption in the country’s diamond industry (Diamantes de Sangue: Tortura e Corrupção em Angola. Tinta da China: Lisboa, 2011), and is developing the anti-corruption watchdog Maka Angola www.makaangola.org. He holds a BA in Anthropology and Media from Goldsmiths College, University of London, and an MSc in African Studies from the University of Oxford. © 2011 by Rafael Marques de Morais. All rights reserved. ii | Corruption in Angola Table of Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 2 I. Consolidation of Presidential Powers: Constitutional and Legal Measures ........................... 4 The Concept of Democracy ......................................................................................................... 4 The Consolidation Process .......................................................................................................... 4 The Consequences ...................................................................................................................... 9 II. Tightening the Net: Available Space for Angolan Civil Society ............................................. -

Negociação Da Normalidade Durante E Após O Conflito Armado Em Malanje, Angola

Escola de Sociologia e Políticas Públicas Dinâmicas da violência política: negociação da normalidade durante e após o conflito armado em Malanje, Angola GILSON LÁZARO Tese submetida como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Doutor em Estudos Africanos Orientador (a): Jean-Michel MABEKO-TALI Professor Catedrático da Howard University, Washington DC Coorientador(a): Doutora Cristina Rodrigues, Investigadora do CEA-IUL Dezembro, 2015 Escola de Sociologia e Políticas Públicas Dinâmicas da violência política: negociação da normalidade durante e após o conflito armado em Malanje, Angola GILSON LÁZARO Júri: Doutora Helena Maria Barroso Carvalho, Professora Auxiliar com agregação do ISCTE- Instituto Universitário de Lisboa Doutor José Carlos Gaspar Venâncio, Professor Catedrático da Universidade da Beira Interior Doutora Sónia Infante Girão Frias Piepoli, Professora Auxiliar do Instituto Superior de Ciências Sociais e Políticas da Universidade de Lisboa Doutor Fernando José Pereira Florêncio, Professor Auxiliar da Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade de Coimbra Doutor Nuno Carlos de Fragoso Vidal, Investigador do Centro de Estudos Internacionais do ISCTE – Instituto Universitário de Lisboa Doutor Jean- Michel Mabeko-Tali, Professor Catedrático do Departamento de História da Universidade de Howard, Washington, DC Doutora Cristina Odete Udelsmann Rodrigues, Investigadora Auxiliar do Centro de Estudos Internacionais do ISCTE – Instituto Universitário de Lisboa Dezembro, 2015 Índice AGRADECIMENTOS ................................................................................................................................... -

Download Folha 8

EDIÇÃONACIONAL KZ250.00 ANO18 EDIÇÃO1154 SÁBADO 10 DEAGOSTO DE/2013 DIRECTOR WILLIAM TONET Discriminação +291dias Judicial Procurador mentiu... O Procurador Geral Adjunto da República, Adão Adriano, mentiu, no dia 06 de Novembro de 2012, ao País sobre o advogado William Tonet, caluniando, difamando e colocando - o no desemprego sem provas. Até hoje nin- guém toma medidas. É a justiça ideológica, Folha WWW.JORNALF8.NET8 submissa e militarizada. REGIME COM LUXO NA MISÉRIA 130 MILHÕES NUM MUNDIAL DE DÓLARES DE HÓQUEI PATINS enquanto 13 MILHÕES MORREM DE FOME regime vai organizar e O gastar no Campeonato Mundial de Hóquei em Patins, a realizar no nosso país, USD 130 milhões de dólares (provavelmente peca por defeito), enquanto 13 milhões de angolanos definham a fome, a sede e não têm serviços básicos de saúde, de educação e emprego. Com tanta miséria é uma insensibilidade que deveria mobilizar-nos a todos como diz o Papa, para exigirmos aos governantes um maior compromisso com a cidadania. Morte no Rocha Paulo Kassoma No Bié Aeroporto de Luanda HOMEM DE SETE OFÍCIOS JOVEM VIOLADA E ASSASSINADA Paulo Kassoma, já foi tanta coisa O crime continua a pulular em Lu- CONSERVADOR FAZ ESQUEMAS CARTÉIS FAZEM FESTA que qualquer dia será coisa tanta, anda e a trazer cenas horripilantes, O conservador do Registo Civil do O aeroporto de Luanda é a principal quando já esteve num pedestal que poderia augurar que um dia, como foi a violação e assassinato da Bié, Aníbal Lumati é acusado de via de entrada de droga em Angola, jovem Jeovania Morais, no fatídico mais tarde, muito mais tarde, ele liderar falcatruas que envergonham reconhece o chefe do departamento pudesse vir a ser presidente da dia 08, precisamente data do seu República de Angola. -

Security Council Distr

UNITED NATIONS Security Council Distr. GENERAL S/1997/640 13 August 1997 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH PROGRESS REPORT OF THE SECRETARY- GENERAL ON THE UNITED ..-,-*(W^vtS-,> NATIONS OBSERVER MISSION IN ANGOLA (MONUA) I . INTRODUCTION 1 . The present report is submitted pursuant to paragraph 3 of Security Council resolution 1118 (1997) of 30 June 1997, by which the Council, inter alia, requested me to report by 15 August 1997 on developments in the Angolan peace process. The present report covers major developments since my last report, dated 5 June 1997 (S/1997/438) . II. POLITICAL ASPECTS 2. During the past two and one-half months, the Angolan peace process continued to experience serious difficulties. In view of the deteriorating military situation and the continued delays in the implementation of the Lusaka Protocol (S/1994/1441, annex), I addressed letters on 3 July 1997 to the President of Angola, Mr. Jose Eduardo dos Santos, and to the leader of the Uniao Nacional para a Independencia Total de Angola (UNITA), Mr. Jonas Savimbi, expressing my serious concern at the increase in tensions in the north-eastern provinces and at the delay in the extension of State administration throughout the country. I also drew their attention to the provisions of Security Council resolution 1118 (1997) and encouraged President dos Santos and Mr. Savimbi to meet, within the national territory of Angola, in order to remove the remaining obstacles to the earliest completion of the Lusaka Protocol. I urged them both to exercise maximum restraint and called on UNITA, in particular, to abide by its commitments under the Protocol.