Signs & Symbols

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes

Signmaking, Chino-Latino Style: Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes _______________________________________________ DAVID A. COLÓN TEXAS CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY Concrete poetry—the aesthetic instigated by the vanguard Noigandres group of São Paulo, in the 1950s—is a hybrid form, as its elements derive from opposite ends of visual comprehension’s spectrum of complexity: literature and design. Using Dick Higgins’s terminology, Claus Clüver concludes that “concrete poetry has taken the same path toward ‘intermedia’ as all the other arts, responding to and simultaneously shaping a contemporary sensibility that has come to thrive on the interplay of various sign systems” (Clüver 42). Clüver is considering concrete poetry in an expanded field, in which the “intertext” poems of the 1970s and 80s include photos, found images, and other non-verbal ephemera in the Concretist gestalt, but even in limiting Clüver’s statement to early concrete poetry of the 1950s and 60s, the idea of “the interplay of various sign systems” is still completely appropriate. In the Concretist aesthetic, the predominant interplay of systems is between literature and design, or, put another way, between words and images. Richard Kostelanetz, in the introduction to his anthology Imaged Words & Worded Images (1970), argues that concrete poetry is a term that intends “to identify artifacts that are neither word nor image alone but somewhere or something in between” (n/p). Kostelanetz’s point is that the hybridity of concrete poetry is deep, if not unmitigated. Wendy Steiner has put it a different way, claiming that concrete poetry “is the purest manifestation of the ut pictura poesis program that I know” (Steiner 531). -

Emojis and Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs

Emojis and Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs Emojis are often compared to Egyptian hieroglyphs because both use pictures to express meaning. However, Egyptian hieroglyphs were a writing system like the alphabet you are reading now and could be used to write anything. Instead of using letters for sounds, the ancient Egyptians used signs (pictures). Emojis are used differently. They add extra meaning to writing, a bit like how tone of voice and gestures add extra meaning when we’re speaking. You could write this paragraph using the emoji-alphabet at the top of the answer sheet, but that’s not how emojis are normally used. Aside from using signs instead of letters, there are lots of differences between the Scots and English writing systems and the ancient Egyptian one. For example, Egyptian hieroglyphs could be written either right to left or left to right and were often written in columns from top to bottom. Hieroglyphic writing didn’t use vowels. The name for this sort of writing system is an abjad. You can write out English and Scots with an abjad rather than an alphabet and still understand it without too much difficulty. For example: Ths sntnc sn’t vry hrd t rd. The biggest difference between alphabetic writing systems and the ancient Egyptian one is that in hieroglyphic writing a sign could be used in three ways. It could be used as a word (ideogram); as a sound (phonogram); or as an idea-sign (determinative) to make things easier to understand. For example, could be used as an ideogram for the word ‘bee’; as a phonogram for the first sound in ‘belief’; or as a determinative added to the end of the word ‘hive’ to distinguish it from ‘have’ and ‘heave’, which would all be written the same: hv. -

Pictograms: Purely Pictorial Symbols

toponymy course 10. Writing systems Ferjan Ormeling This chapter shows the semantic, phonetic and graphic aspects of language. It traces the development of the graphic aspects from Sumeria 3500BC, from logographic or ideographic via syllabic into alphabetic scripts resulting in a number of script families. It gives examples of the various scripts in maps (see underlined script names) and finally deals with combination of scripts on maps. 03/07/2011 1 Meaning, sound and looks What is the name? - Is it what it means? - Is it what it sounds? - Is it what it looks? 03/07/2011 2 Meaning: the semantic aspect As long as a name is what it means, both its sound and its looks (spelling) are only relevant as far as they support the meaning. The name ‘Nederland’ is wat it means to our neighbours: ‘Low country’. So they translate it for instance into ‘Pays- Bas’ (French) or Netherlands (English) or Niederlande (German), even though that does neither sound nor look like ‘Nederland’. To Romans and Italians, however, the names Qart Hadasht and Neapolis had never been what they meant (‘new towns’). So they became what they sounded: Carthago (to the Roman ear) and Napoli. 03/07/2011 3 Sound: the phonetic aspect As soon as a name is what it sounds, its meaning has become irrelevant. Its looks (spelling) then may or may not be adapted to its sound. The dominance of the phonetic aspect to a name (the ‘oral tradition’) allows the name to degenerate graphically. Eventually, the name may be adapted semantically to its perceived sound, through a process called ‘popular etymology’. -

The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized

American Journal of Applied Psychology 2017; 6(5): 88-92 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ajap doi: 10.11648/j.ajap.20170605.11 ISSN: 2328-5664 (Print); ISSN: 2328-5672 (Online) The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized Marcienne Martin ORACLE Laboratory, Observatory of Arts, Civilizations and Literatures, in Their Environment, University of Reunion Island, France Email address: [email protected] To cite this article: Marcienne Martin. The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized. American Journal of Applied Psychology. Vol. 6, No. 5, 2017, pp. 88-92. doi: 10.11648/j.ajap.20170605.11 Received: January 16, 2017; Accepted: January 25, 2017; Published: October 18, 2017 Abstract: The digital paradigm to which these new technologies (NTIC) belong is at the origin of particular linguistic practices. Internet is an innovator in this field. Indeed, its users want their written communications to be as fast as during oral exchanges; they will choose their knowledge to write on a saving in expressive type. Also wishing to transmit feelings and emotions, they will call upon an iconography, which uses the diacritics as material serving creation of logograms. This redundancy of a diverted punctuation of its original use, but being used “to punctuate” the speech by figurines translating the emotional state of the speaker, is a characteristic of this numerical space. Through the analysis of the corpus taken on the Internet and put in comparison with the hieroglyphic system introduced by Champollion Le Jeune [5] and the graphic evolution of some ideograms, it will be shown that it is always about the same used model, in which a key always initiates a semantic field, and that this process orders a reorganization of the objects of the world through a new scriptural writing. -

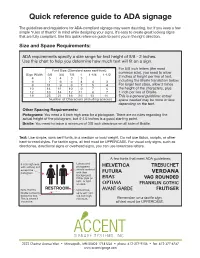

Quick Reference Guide to ADA Signage

Quick reference guide to ADA signage The guidelines and regulations for ADA-compliant signage may seem daunting, but if you keep a few simple “rules of thumb” in mind while designing your signs, it’s easy to create great looking signs that are fully compliant. Use this quick reference guide to point you in the right direction. Size and Space Requirements: ADA requirements specify a size range for text height of 5/8 - 2 inches. Use this chart to help you determine how much text will fit on a sign. For 5/8 inch letters (the most common size), you need to allow 2 inches of height per line of text, including the Braille translation below. For larger text sizes, allow 2 times the height of the characters, plus 1 inch per line of Braille. This is a general guideline; actual space needed may be more or less depending on the text. Other Spacing Requirements: Pictograms: You need a 6 inch high area for a pictogram. There are no rules regarding the actual height of the pictogram, but 4-4.5 inches is a good starting point. Braille: You need to leave a minimum of 3/8 inch clearance on all side of Braille. Text: Use simple, sans serif fonts, in a medium or bold weight. Do not use italics, scripts, or other hard-to-read styles. For tactile signs, all text must be UPPERCASE. For visual only signs, such as directories, directional signs or overhead signs, you can use lowercase letters. A few fonts that meet ADA guidelines: 6 inch high area Letters and with nothing in it pictograms except the should contrast pictogram. -

A STUDY of WRITING Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu /MAAM^MA

oi.uchicago.edu A STUDY OF WRITING oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu /MAAM^MA. A STUDY OF "*?• ,fii WRITING REVISED EDITION I. J. GELB Phoenix Books THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS oi.uchicago.edu This book is also available in a clothbound edition from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS TO THE MOKSTADS THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada Copyright 1952 in the International Copyright Union. All rights reserved. Published 1952. Second Edition 1963. First Phoenix Impression 1963. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE HE book contains twelve chapters, but it can be broken up structurally into five parts. First, the place of writing among the various systems of human inter communication is discussed. This is followed by four Tchapters devoted to the descriptive and comparative treatment of the various types of writing in the world. The sixth chapter deals with the evolution of writing from the earliest stages of picture writing to a full alphabet. The next four chapters deal with general problems, such as the future of writing and the relationship of writing to speech, art, and religion. Of the two final chapters, one contains the first attempt to establish a full terminology of writing, the other an extensive bibliography. The aim of this study is to lay a foundation for a new science of writing which might be called grammatology. While the general histories of writing treat individual writings mainly from a descriptive-historical point of view, the new science attempts to establish general principles governing the use and evolution of writing on a comparative-typological basis. -

ICA Course on Toponymy

S10: Writing systems 2. SCRIPTS, THE GRAPHICS OF LANGUAGE <previous - next> The cradle of most of the modern phonographic scripts is the Middle East. The oldest known Sumerian and Home Egyptian pictographic inscriptions considered to be scripts date from the 4th millennium BC. | Self study : Scripts were developed to extend man’s scope and range. Writing Systems | Pictograms: purely pictorial symbols. Contents | Pictograms were used to represent the concepts (ideograms) or words (logograms) they represented. Intro | 1.Meaning, Ultimately, logograms develop into phonograms, in which the sound value (phoneme) of mono- sound & looks (a/b/c) syllabic words is attached to the symbols representing these words. | 2.Scripts | Finally the syllabic script develops into an alphabetic script in which symbols represent single 3.Script phonemes instead of syllables. development | 4.Division Universal sequence from purely pictorial representation (pictograms) to sets of abstracted sound- | 5.Basic unit representing symbols (phonograms). of writing Pictograms convey meaning without intervention of sound values; there may be a symbol meaning ‘town’, | ‘river’ or ‘mountain’ irrespective of what the word for ‘town’, ‘river’ or ‘mountain’ sounds like, and thus 6.Logograms | regardless of any specific language. Such a symbol is named a logogram (pictogram for a specific word). 7.Ideographic The advantage of logograms is their universal applicability – because they are language-independent – but and they have the obvious disadvantage that there must be a separate symbol for every word. logographic scripts | All complete writing systems the world has ever known, do effectively contain both logograms and 8.Syllabic phonograms. As purely pictorial ‘proto-scripts’ develop into ‘scripts’ or writing systems, naturally drawn scripts pictograms are stylised and augmented with drawings for abstract phenomena (hence called ideograms), | 9.Alphabetic and will ultimately contain logograms for all basic words of a specific language. -

Pictograms and Visual Cognition

Damian Goidich Professor Diane Zeeuw New Visual Studies April 5, 2011 Pictograms and Visual Cognition Pictograms are a unique addition to the history of our pictorial language. Initially devised as a 20th century solution to the complications created by the globalization of mass transit, communication and travel, their effectiveness at transmitting messages, commands and direction through a distinct set of graphic shapes, symbols and colors has revolutionized how we visually interpret images and communicate on an international scale in the 21st century. Pictograms as a visual form of communication have their roots in ancient civilizations dating back to the fourth millennium BCE. The earliest use of pictograms as a form of communication or “writing” is generally attributed to the Sumerian civilization circa 3500 BCE (Fig. 1). While little is known of the details surrounding their culture, archaeological evidence suggests that their use of cuneiforms was a specialized form of object representation used to record, amongst other things, economic transactions such as the buying and selling of livestock and foodstuffs (Frutiger 119-20). This form of communication through images has continued virtually uninterrupted down through the historical timeline, being well documented in the cultures of Egypt, China, the Middle East, the Mayan and Aztec civilizations of Mesoamerica, and throughout Medieval Europe. The 20th century brought about a tremendous acceleration in the fields of technology, most evident in the invention and proliferation of the automobile which effected both national and international commerce. This led to the development of an extensive grid of roads and highways necessary for the accommodation of the burgeoning mobile culture. -

The Story of Writing: Alphabets, Hieroglyphs and Pictograms Free

FREE THE STORY OF WRITING: ALPHABETS, HIEROGLYPHS AND PICTOGRAMS PDF Andrew Robinson | 232 pages | 01 May 2007 | Thames & Hudson Ltd | 9780500286609 | English | London, United Kingdom Ancient Egypt's cryptic hieroglyphs | Nature A pictogram or pictograph is a symbol representing a concept, object, activity, place or event by illustration. Pictography is a form of writing whereby ideas are transmitted through drawing. It is the basis of cuneiform and hieroglyphs. Early written symbols were based on pictograms pictures which resemble what they signify and ideograms Hieroglyphs and Pictograms which represent ideas. It is commonly believed that pictograms appeared before ideograms. They were used by various ancient cultures all Hieroglyphs and Pictograms the world since around BC and began to develop into logographic writing systems around BC. Pictograms are still in use as the main medium of written communication in some non-literate cultures in Africa, The Americas, and Oceania, and are often used as simple symbols by most contemporary cultures. An ideogram or ideograph is a graphical symbol that represents an idea, rather than a group of letters arranged according to the phonemes of a spoken language, as is done in alphabetic languages. Examples of ideograms include wayfinding signage, such as in airports and other environments where many people may not be familiar with the language of the place they are in, as well as Arabic numerals and mathematical notation, which are used worldwide regardless of how they are pronounced in different languages. The term "ideogram" is commonly used to describe logographic writing systems such as Egyptian hieroglyphs and Chinese characters. However, symbols in logographic systems generally represent words or morphemes rather than pure ideas. -

Chapter 6, Writing Systems and Punctuation

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

Computational Pattern Recognition in Linear a Jajwalya Karajgikar, Amira Al-Khulaidy, Anamaria Berea

Computational Pattern Recognition in Linear A Jajwalya Karajgikar, Amira Al-Khulaidy, Anamaria Berea To cite this version: Jajwalya Karajgikar, Amira Al-Khulaidy, Anamaria Berea. Computational Pattern Recognition in Linear A. In press. hal-03207615 HAL Id: hal-03207615 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03207615 Preprint submitted on 26 Apr 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Computational Pattern Recognition in Linear A Jajwalya R. Karajgikar1*, Amira Al-Khulaidy 2 , Anamaria Berea3 1 Computational Sciences, MS, George Mason University 2 Computational Social Sciences, PhD student, George Mason University 3 Computational and Data Sciences, Associate Professor, George Mason University *Corresponding author: Jajwalya R. Karajgikar1 Abstract Linear A is an ancient Mycenaean Greek language that is as of yet undeciphered. Computational analysis of the symbols using natural language processing and data mining techniques can aid to better understand this logogram language, and to help us uncover interesting statistical and information-theoretic patterns even without deciphering the language. Using information theory and data science techniques, we show an exploratory analysis of these symbols. We use n-gram analysis to summarize and predict the possible symbols on lost stone tablets, while symbols are clustered by topic modeling as well as k-means, for comparison. -

Interface Aesthetics Week 8 Signs, Pictograms, and Icons

Interface Aesthetics Week 8 Signs, pictograms, and icons Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 OUTLINE - Semiotics - Building symbols - Pictograms - Icons - Logos Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 INTERFACE AESTHETICS Assignment 5 Design a new pictogram/ logo/icon for: • I School, or • Your school or program (non-I School), or • Your own project Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 Semiotics: The study of signs Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 SIGNS Signified Signifier Sense The physical thing or The representation of The understanding idea that the sign the object, which that an observer gets stands for. could be a word, a from seeing or picture, or a sound. experiencing either the signified or its signifier. Warm, hot, burn, bright, dangerous, etc. Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 Signs - Symbolic - Iconic - Indexical [Charles Sanders Peirce, 1839-1914] Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 SIGNS Symbolic signs Code or rule-following conventions required Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 SIGNS Symbolic signs Language characters, numbers Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 AMBIENT MEDIA Orb [Ambient Devices] Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 AMBIENT MEDIA Orb [Ambient Devices] Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 SIGNS Symbolic signs Abstract visual representations Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 SIGNS Iconic signs An intermediate degree of transparency to the signified object Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 SIGNS Iconic signs Drawings and caricatures Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 SIGNS Iconic signs Metaphors [Jeremijenko , 1995] Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 SIGNS Indexical signs Directly connected to the signified. Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 Indexical signs Natural signs 16 Jason Courtney http://www.perdador.com/f6update/Oc3.html SIGNS Indexical signs Measuring instruments (scale, thermometer, clock) Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 Indexical signs Countdowns 18 SIGNS Symbolic Iconic Indexical Language Drawings, Measuring characters, caricatures, instruments numbers, metaphors abstract mapping (e.g.