Pictographs, Ideograms, and Alphabets in the Work of Paul Klee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes

Signmaking, Chino-Latino Style: Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes _______________________________________________ DAVID A. COLÓN TEXAS CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY Concrete poetry—the aesthetic instigated by the vanguard Noigandres group of São Paulo, in the 1950s—is a hybrid form, as its elements derive from opposite ends of visual comprehension’s spectrum of complexity: literature and design. Using Dick Higgins’s terminology, Claus Clüver concludes that “concrete poetry has taken the same path toward ‘intermedia’ as all the other arts, responding to and simultaneously shaping a contemporary sensibility that has come to thrive on the interplay of various sign systems” (Clüver 42). Clüver is considering concrete poetry in an expanded field, in which the “intertext” poems of the 1970s and 80s include photos, found images, and other non-verbal ephemera in the Concretist gestalt, but even in limiting Clüver’s statement to early concrete poetry of the 1950s and 60s, the idea of “the interplay of various sign systems” is still completely appropriate. In the Concretist aesthetic, the predominant interplay of systems is between literature and design, or, put another way, between words and images. Richard Kostelanetz, in the introduction to his anthology Imaged Words & Worded Images (1970), argues that concrete poetry is a term that intends “to identify artifacts that are neither word nor image alone but somewhere or something in between” (n/p). Kostelanetz’s point is that the hybridity of concrete poetry is deep, if not unmitigated. Wendy Steiner has put it a different way, claiming that concrete poetry “is the purest manifestation of the ut pictura poesis program that I know” (Steiner 531). -

Emojis and Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs

Emojis and Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs Emojis are often compared to Egyptian hieroglyphs because both use pictures to express meaning. However, Egyptian hieroglyphs were a writing system like the alphabet you are reading now and could be used to write anything. Instead of using letters for sounds, the ancient Egyptians used signs (pictures). Emojis are used differently. They add extra meaning to writing, a bit like how tone of voice and gestures add extra meaning when we’re speaking. You could write this paragraph using the emoji-alphabet at the top of the answer sheet, but that’s not how emojis are normally used. Aside from using signs instead of letters, there are lots of differences between the Scots and English writing systems and the ancient Egyptian one. For example, Egyptian hieroglyphs could be written either right to left or left to right and were often written in columns from top to bottom. Hieroglyphic writing didn’t use vowels. The name for this sort of writing system is an abjad. You can write out English and Scots with an abjad rather than an alphabet and still understand it without too much difficulty. For example: Ths sntnc sn’t vry hrd t rd. The biggest difference between alphabetic writing systems and the ancient Egyptian one is that in hieroglyphic writing a sign could be used in three ways. It could be used as a word (ideogram); as a sound (phonogram); or as an idea-sign (determinative) to make things easier to understand. For example, could be used as an ideogram for the word ‘bee’; as a phonogram for the first sound in ‘belief’; or as a determinative added to the end of the word ‘hive’ to distinguish it from ‘have’ and ‘heave’, which would all be written the same: hv. -

A STUDY of WRITING Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu /MAAM^MA

oi.uchicago.edu A STUDY OF WRITING oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu /MAAM^MA. A STUDY OF "*?• ,fii WRITING REVISED EDITION I. J. GELB Phoenix Books THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS oi.uchicago.edu This book is also available in a clothbound edition from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS TO THE MOKSTADS THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada Copyright 1952 in the International Copyright Union. All rights reserved. Published 1952. Second Edition 1963. First Phoenix Impression 1963. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE HE book contains twelve chapters, but it can be broken up structurally into five parts. First, the place of writing among the various systems of human inter communication is discussed. This is followed by four Tchapters devoted to the descriptive and comparative treatment of the various types of writing in the world. The sixth chapter deals with the evolution of writing from the earliest stages of picture writing to a full alphabet. The next four chapters deal with general problems, such as the future of writing and the relationship of writing to speech, art, and religion. Of the two final chapters, one contains the first attempt to establish a full terminology of writing, the other an extensive bibliography. The aim of this study is to lay a foundation for a new science of writing which might be called grammatology. While the general histories of writing treat individual writings mainly from a descriptive-historical point of view, the new science attempts to establish general principles governing the use and evolution of writing on a comparative-typological basis. -

Chapter 6, Writing Systems and Punctuation

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

Computational Pattern Recognition in Linear a Jajwalya Karajgikar, Amira Al-Khulaidy, Anamaria Berea

Computational Pattern Recognition in Linear A Jajwalya Karajgikar, Amira Al-Khulaidy, Anamaria Berea To cite this version: Jajwalya Karajgikar, Amira Al-Khulaidy, Anamaria Berea. Computational Pattern Recognition in Linear A. In press. hal-03207615 HAL Id: hal-03207615 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03207615 Preprint submitted on 26 Apr 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Computational Pattern Recognition in Linear A Jajwalya R. Karajgikar1*, Amira Al-Khulaidy 2 , Anamaria Berea3 1 Computational Sciences, MS, George Mason University 2 Computational Social Sciences, PhD student, George Mason University 3 Computational and Data Sciences, Associate Professor, George Mason University *Corresponding author: Jajwalya R. Karajgikar1 Abstract Linear A is an ancient Mycenaean Greek language that is as of yet undeciphered. Computational analysis of the symbols using natural language processing and data mining techniques can aid to better understand this logogram language, and to help us uncover interesting statistical and information-theoretic patterns even without deciphering the language. Using information theory and data science techniques, we show an exploratory analysis of these symbols. We use n-gram analysis to summarize and predict the possible symbols on lost stone tablets, while symbols are clustered by topic modeling as well as k-means, for comparison. -

COX-DISSERTATION-2018.Pdf (5.765Mb)

Copyright Copyright by Benjamin Davis Cox 2018 Signature Page The Dissertation Committee for Benjamin Davis Cox certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Gods Without Faces Childhood, Religion, and Imagination in Contemporary Japan Committee: ____________________________________ John W. Traphagan, Supervisor ____________________________________ A. Azfar Moin ____________________________________ Oliver Freiberger ____________________________________ Kirsten Cather Title Page Gods Without Faces Childhood, Religion, and Imagination in Contemporary Japan by Benjamin Davis Cox Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2018 Dedication For my mother, who tirelessly read all of my blasphemies, but corrected only my grammar. BB&tt. Acknowledgments Fulbright, CHLA This research was made possible by the Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship, a Hannah Beiter Graduate Student Research Grant from the Children’s Literature Association, and a grant from the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Endowment in the College of Liberal Arts, University of Texas at Austin. I would additionally like to thank Waseda University for sponsoring my research visa, and in particular Glenda Roberts for helping secure my affiliation. Thank you to the members of my committee—John Traphagan, Azfar Moin, Oliver Freiberger, and Kirsten Cather—for their years of support and intellectual engagement, and to my ‘grand-advisor’ Keith Brown, whose lifetime of work in Mizusawa opened many doors to me that would otherwise have remained firmly but politely shut. I am deeply indebted to the people of Mizusawa for their warmth, kindness, and forbearance. -

The Alphabet Tree Dren’S Puzzles

TUGboat, Volume 26 (2005), No. 3 199 A major intellectual step was the invention of Philology the rebus device. This is where the sounds cor- responding to pictograms are combined to form a word. We have all come across these, often as chil- The alphabet tree dren’s puzzles. For example, a picture of a bee Peter Wilson plus a picture of a tray can represent the word ‘be- tray’, or more obscurely a picture of a bee plus a 1 Introduction picure of a female deer can stand for the word ‘be- We got from via Akn and ’ k n to hind’. Even a single pictogram can suffice; for in- XPD stance a pictogram of the sun can be used for both ` k p A K N, and and @ ¼ à in only about 2000 the words ‘sun’ and ‘son’. Consequently symbols years. This is a short story of how that happened can be created that just stand for sounds and then and how we know what the strange symbols mean, they can be combined to form words. This can a k n a k n e.g., and . The fonts in all the markedly reduce the number of symbols required for examples were designed for use with TEX, especially a full writing system. Symbols representing sounds by humanities scholars, and are freely available. are called phonograms. Phonetic writing requires 1.1 Writing systems few glyphs. In these writing systems, the glyphs represent sounds. All writing systems are a com- The earliest known writing is from Sumeria dating bination of phonetic and logographic elements but from about 3400 bc. -

Abjad 1 Abjad Numerals 6 References Article Sources and Contributors 9 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 10 Article Licenses License 11 Abjad 1 Abjad

al-ʾAbǧad Two Wikipedia Articles PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 30 Sep 2013 21:20:08 UTC Contents Articles Abjad 1 Abjad numerals 6 References Article Sources and Contributors 9 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 10 Article Licenses License 11 Abjad 1 Abjad An abjad is a type of writing system where each symbol always or usually stands for a consonant, leaving the reader to supply the appropriate vowel. It is a term suggested by Peter T. Daniels to replace the common terms "consonantary", "consonantal alphabet" or "syllabary" to refer to the family of scripts called West Semitic. Abjad is thought to be based on the first letters (a,b,ǧ,d) found in all Semitic language such as Phoenician, Syriac, Hebrew, and Arabic. In Arabic, "A" (ʾAlif), "B" (Bāʾ), "Ǧ" (Ǧīm), "D" (Dāl) make the word "abjad" which means "alphabet". The modern Arabic word for "alphabet" and "abjad" is interchangeably either "abajadeyyah" or "alefbaaeyyah". The word "alphabet" in English has a source in Greek language in which the first two letters were "A" (alpha) and "B" (beta), hence "alphabeta" (in Spanish, "alfabeto", but also called "abecedario", from "a" "b" "c" "d"). In Hebrew the first two letters are "A" (Aleph), "B" (Bet) hence "alephbet." It is also used to enumerate a list in the same manner that "a, b, c, d" (etc.) are used in the English language. Writing systems • History • Grapheme • List of writing systems Types • Featural alphabet • Alphabet • Abjad • Abugida • Syllabary • Logography • Shorthand Related topics • Pictogram • Ideogram Etymology is derived from pronouncing the first letters of the Arabic alphabet in order. -

Two Advantages to a Writing System: 1

LING 110 Chapter IV: The Alphabet • Introduction – One of the most important inventions in human history. – Two Advantages to a writing system: 1. Allows us to communicate with others outside of shouting range. 2. An extension to our memory. Ling 110 Chapter IV: The Alphabet 1 LING 110 The History of Writing • There are many legends and stories about the invention of writing. – Greek Legend: Cadmus, prince of Phoenicia and founder of the city of Thebes, invented the alphabet and brought it with him to Greece. – Chinese Fable: the four-eyed dragon-god Cang Jie invented writing. – Icelandic Saga: Odin was the inventor or runic script. Ling 110 Chapter IV: The Alphabet 2 LING 110 The History of Writing con’t • However, it is evident that, before a single word wa written, uncountable billions were spoken. • Therefore, it is unlikely that a particularly gifted ancestor awoke one morning and decided, “Today I’ll invent a writing system.” • In fact, the invention of writing systems comes relatively late in human history, and its development was gradual. Ling 110 Chapter IV: The Alphabet 3 DifferentDifferent TypesTypes ofof WritingWriting SystemsSystems Different Writing Systems • We can distinguish among a number of different writing systems based on what the symbols represent. 1. Petroglyphs: • Cave drawings, drawn by people living more than 20, 000 years ago, can still be ‘read’ today. • They are literal portrayals of life at that time. • They may be aesthetic expressions rather than pictorial communications. • Example: Altamira cave in northern Spain. Ling 110 Chapter IV: The Alphabet 4 DifferentDifferent TypesTypes ofof WritingWriting SystemsSystems 2. -

Edward L. Shaughnessy Chinese Annals in the Western Observatory Library of Sinology

Edward L. Shaughnessy Chinese Annals in the Western Observatory Library of Sinology Editors Zhi Chen, Dirk Meyer Executive Editor Adam C. Schwartz Editorial Board Wolfgang Behr, Marc Kalinowski, Hans van Ess, Bernhard Fuehrer, Anke Hein, Clara Wing-chung Ho, Maria Khayutina, Michael Lackner, Yuri Pines, Alain Thote, Nicholas Morrow Williams Volume 4 Edward L. Shaughnessy Chinese Annals in the Western Observatory An Outline of Western Studies of Chinese Unearthed Documents The publication of the series has been supported by the HKBU Jao Tsung-I Academy of Sinology — Amway Development Fund. ISBN 978-1-5015-1693-1 e-ISBN [PDF] 978-1-5015-1694-8 e-ISBN [EPUB] 978-1-5015-1710-5 ISSN 2625-0616 This work is licensed under the Creatice Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019953355 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Shaughnessy/JAS, published by Walter de Gruyter Inc., Boston/Berlin Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Dedicated to the memory of LI Xueqin 李學勤 (1933-2019) 南山有杞,北山有李。 樂只君子,德音不已。 On South Mountain is a willow, On North Mountain is a plum tree. Such joy has the noble-man brought, Sounds of virtue never ending. CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES | XI PREFACE TO THE CHINESE EDITION | -

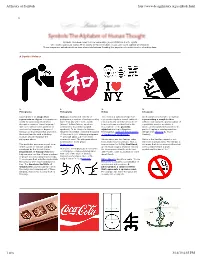

A History of Symbols

A History of Symbols http://www.designhistory.org/symbols.html > Symbols have been used to show ownership, group affiliations and to signify who made a particular object. They convey direct information or can carry quiet subliminal messages. These images are edited selections from class slide lectures. Reading this page is not a substitute for attending class. A Symbol Primer 1. 1. 2. 3. Pictograms Pictograms Rebus Ideogram A pictogram is an image that Chinese is composed entirely of The rebus is a pictorial image that An ideogram is a character or symbol represents an object. Pictograms are pictograms, a system of writing used by represents a spoken sound. Today the representing a complete idea useful for conveying information more than any other in the world. rebus is mostly used for amusement without expressing the pronunciation of through a common "visual language" (About 1 billion Chinese speakers however it was a critical link in the a particular word or words for it. able to be understood regardless of compared to 350 million English development of the phonetic Above, an ideogram demonstrates the one's native language or degree of speakers). To be literate in Chinese alphabet starting in Egyptian perils of tipping a vending machine. literacy. So that means that anyone in requires knowledge of several thousand hieroglyphics. (See the "Development (Image from Warning by Nicole the world familiar with a drinking of the over 80,000 Chinese pictograms of Handwriting" on this site). Recchia) fountain should recognize the — although about 3,500 are most pictogram above. commonly used. The pictogram above Shown above are two famous rebus Below is the familiar request to not is Chinese for world peace logos from the 20th century. -

Chinese Writing and Abstract Thought: a Historical-Sociological Critique of a Longstanding Thesis

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 4, No. 8(1); June 2014 Chinese Writing and Abstract Thought: A Historical-Sociological Critique of a Longstanding Thesis Raymond W.K. Lau, PhD Professor in Sociology School of Arts & Social Sciences The Open University of Hong Kong 30 Good Shepherd Street Homantin, Kowloon Hong Kong Abstract For centuries, numerous Western scholars have argued that Chinese writing is concrete-bound and hence inhibitive of abstract thought in pre-modern China, while alphabetic writing is abstract, and hence enabling of abstract thought. This longstanding and popular view, while originating in Europe, has also had considerable impact in Chinese and other non-Western academic circles. The present paper devises a special-purpose historical-sociological framework in order to examine, in a theoretically-informed way, writing’s invention and subsequent development in Mesopotamia/East Mediterranean area and China, on the basis of which the concrete- bound-versus-abstract distinction between different writing systems is debunked. The claim concerning the supposed effects of writing system on mode of thinking is then shown to be theoretically vacuous, logically illegitimate, and empirically ill-informed concerning ancient Chinese thoughts. The present paper’s analysis complements that of scholars who show that the ancient Chinese language was not (grammatically or otherwise) inhibitive of abstract logical thought and reasoning. Keywords: Chinese writing and abstract thought, alphabetic writing and abstract thought, alphabetic literacy theory 1. Introduction Early in his career, French sociologist-cum-sinologist Marcel Granet commented on Chinese writing as follows: [Western languages] are instruments of analysis which allow one to define classes, which teach one to think logically, and which also make it easy to transmit in a clear and distinct fashion a very elaborate way of thinking.