Modes of Transcription in Natural Languages. INSTITUTION Monash Univ., Clayton, Victoria (Australia)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes

Signmaking, Chino-Latino Style: Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes _______________________________________________ DAVID A. COLÓN TEXAS CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY Concrete poetry—the aesthetic instigated by the vanguard Noigandres group of São Paulo, in the 1950s—is a hybrid form, as its elements derive from opposite ends of visual comprehension’s spectrum of complexity: literature and design. Using Dick Higgins’s terminology, Claus Clüver concludes that “concrete poetry has taken the same path toward ‘intermedia’ as all the other arts, responding to and simultaneously shaping a contemporary sensibility that has come to thrive on the interplay of various sign systems” (Clüver 42). Clüver is considering concrete poetry in an expanded field, in which the “intertext” poems of the 1970s and 80s include photos, found images, and other non-verbal ephemera in the Concretist gestalt, but even in limiting Clüver’s statement to early concrete poetry of the 1950s and 60s, the idea of “the interplay of various sign systems” is still completely appropriate. In the Concretist aesthetic, the predominant interplay of systems is between literature and design, or, put another way, between words and images. Richard Kostelanetz, in the introduction to his anthology Imaged Words & Worded Images (1970), argues that concrete poetry is a term that intends “to identify artifacts that are neither word nor image alone but somewhere or something in between” (n/p). Kostelanetz’s point is that the hybridity of concrete poetry is deep, if not unmitigated. Wendy Steiner has put it a different way, claiming that concrete poetry “is the purest manifestation of the ut pictura poesis program that I know” (Steiner 531). -

Pictograms: Purely Pictorial Symbols

toponymy course 10. Writing systems Ferjan Ormeling This chapter shows the semantic, phonetic and graphic aspects of language. It traces the development of the graphic aspects from Sumeria 3500BC, from logographic or ideographic via syllabic into alphabetic scripts resulting in a number of script families. It gives examples of the various scripts in maps (see underlined script names) and finally deals with combination of scripts on maps. 03/07/2011 1 Meaning, sound and looks What is the name? - Is it what it means? - Is it what it sounds? - Is it what it looks? 03/07/2011 2 Meaning: the semantic aspect As long as a name is what it means, both its sound and its looks (spelling) are only relevant as far as they support the meaning. The name ‘Nederland’ is wat it means to our neighbours: ‘Low country’. So they translate it for instance into ‘Pays- Bas’ (French) or Netherlands (English) or Niederlande (German), even though that does neither sound nor look like ‘Nederland’. To Romans and Italians, however, the names Qart Hadasht and Neapolis had never been what they meant (‘new towns’). So they became what they sounded: Carthago (to the Roman ear) and Napoli. 03/07/2011 3 Sound: the phonetic aspect As soon as a name is what it sounds, its meaning has become irrelevant. Its looks (spelling) then may or may not be adapted to its sound. The dominance of the phonetic aspect to a name (the ‘oral tradition’) allows the name to degenerate graphically. Eventually, the name may be adapted semantically to its perceived sound, through a process called ‘popular etymology’. -

The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized

American Journal of Applied Psychology 2017; 6(5): 88-92 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ajap doi: 10.11648/j.ajap.20170605.11 ISSN: 2328-5664 (Print); ISSN: 2328-5672 (Online) The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized Marcienne Martin ORACLE Laboratory, Observatory of Arts, Civilizations and Literatures, in Their Environment, University of Reunion Island, France Email address: [email protected] To cite this article: Marcienne Martin. The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized. American Journal of Applied Psychology. Vol. 6, No. 5, 2017, pp. 88-92. doi: 10.11648/j.ajap.20170605.11 Received: January 16, 2017; Accepted: January 25, 2017; Published: October 18, 2017 Abstract: The digital paradigm to which these new technologies (NTIC) belong is at the origin of particular linguistic practices. Internet is an innovator in this field. Indeed, its users want their written communications to be as fast as during oral exchanges; they will choose their knowledge to write on a saving in expressive type. Also wishing to transmit feelings and emotions, they will call upon an iconography, which uses the diacritics as material serving creation of logograms. This redundancy of a diverted punctuation of its original use, but being used “to punctuate” the speech by figurines translating the emotional state of the speaker, is a characteristic of this numerical space. Through the analysis of the corpus taken on the Internet and put in comparison with the hieroglyphic system introduced by Champollion Le Jeune [5] and the graphic evolution of some ideograms, it will be shown that it is always about the same used model, in which a key always initiates a semantic field, and that this process orders a reorganization of the objects of the world through a new scriptural writing. -

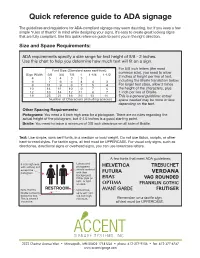

Quick Reference Guide to ADA Signage

Quick reference guide to ADA signage The guidelines and regulations for ADA-compliant signage may seem daunting, but if you keep a few simple “rules of thumb” in mind while designing your signs, it’s easy to create great looking signs that are fully compliant. Use this quick reference guide to point you in the right direction. Size and Space Requirements: ADA requirements specify a size range for text height of 5/8 - 2 inches. Use this chart to help you determine how much text will fit on a sign. For 5/8 inch letters (the most common size), you need to allow 2 inches of height per line of text, including the Braille translation below. For larger text sizes, allow 2 times the height of the characters, plus 1 inch per line of Braille. This is a general guideline; actual space needed may be more or less depending on the text. Other Spacing Requirements: Pictograms: You need a 6 inch high area for a pictogram. There are no rules regarding the actual height of the pictogram, but 4-4.5 inches is a good starting point. Braille: You need to leave a minimum of 3/8 inch clearance on all side of Braille. Text: Use simple, sans serif fonts, in a medium or bold weight. Do not use italics, scripts, or other hard-to-read styles. For tactile signs, all text must be UPPERCASE. For visual only signs, such as directories, directional signs or overhead signs, you can use lowercase letters. A few fonts that meet ADA guidelines: 6 inch high area Letters and with nothing in it pictograms except the should contrast pictogram. -

The Origin of the Alphabet: an Examination of the Goldwasser Hypothesis

Colless, Brian E. The origin of the alphabet: an examination of the Goldwasser hypothesis Antiguo Oriente: Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente Vol. 12, 2014 Este documento está disponible en la Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad Católica Argentina, repositorio institucional desarrollado por la Biblioteca Central “San Benito Abad”. Su objetivo es difundir y preservar la producción intelectual de la Institución. La Biblioteca posee la autorización del autor para su divulgación en línea. Cómo citar el documento: Colless, Brian E. “The origin of the alphabet : an examination of the Goldwasser hypothesis” [en línea], Antiguo Oriente : Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente 12 (2014). Disponible en: http://bibliotecadigital.uca.edu.ar/repositorio/revistas/origin-alphabet-goldwasser-hypothesis.pdf [Fecha de consulta:..........] . 03 Colless - Alphabet_Antiguo Oriente 09/06/2015 10:22 a.m. Página 71 THE ORIGIN OF THE ALPHABET: AN EXAMINATION OF THE GOLDWASSER HYPOTHESIS BRIAN E. COLLESS [email protected] Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand Summary: The Origin of the Alphabet Since 2006 the discussion of the origin of the Semitic alphabet has been given an impetus through a hypothesis propagated by Orly Goldwasser: the alphabet was allegedly invented in the 19th century BCE by illiterate Semitic workers in the Egyptian turquoise mines of Sinai; they saw the picturesque Egyptian inscriptions on the site and borrowed a number of the hieroglyphs to write their own language, using a supposedly new method which is now known by the technical term acrophony. The main weakness of the theory is that it ignores the West Semitic acrophonic syllabary, which already existed, and contained most of the letters of the alphabet. -

A STUDY of WRITING Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu /MAAM^MA

oi.uchicago.edu A STUDY OF WRITING oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu /MAAM^MA. A STUDY OF "*?• ,fii WRITING REVISED EDITION I. J. GELB Phoenix Books THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS oi.uchicago.edu This book is also available in a clothbound edition from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS TO THE MOKSTADS THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada Copyright 1952 in the International Copyright Union. All rights reserved. Published 1952. Second Edition 1963. First Phoenix Impression 1963. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE HE book contains twelve chapters, but it can be broken up structurally into five parts. First, the place of writing among the various systems of human inter communication is discussed. This is followed by four Tchapters devoted to the descriptive and comparative treatment of the various types of writing in the world. The sixth chapter deals with the evolution of writing from the earliest stages of picture writing to a full alphabet. The next four chapters deal with general problems, such as the future of writing and the relationship of writing to speech, art, and religion. Of the two final chapters, one contains the first attempt to establish a full terminology of writing, the other an extensive bibliography. The aim of this study is to lay a foundation for a new science of writing which might be called grammatology. While the general histories of writing treat individual writings mainly from a descriptive-historical point of view, the new science attempts to establish general principles governing the use and evolution of writing on a comparative-typological basis. -

ICA Course on Toponymy

S10: Writing systems 2. SCRIPTS, THE GRAPHICS OF LANGUAGE <previous - next> The cradle of most of the modern phonographic scripts is the Middle East. The oldest known Sumerian and Home Egyptian pictographic inscriptions considered to be scripts date from the 4th millennium BC. | Self study : Scripts were developed to extend man’s scope and range. Writing Systems | Pictograms: purely pictorial symbols. Contents | Pictograms were used to represent the concepts (ideograms) or words (logograms) they represented. Intro | 1.Meaning, Ultimately, logograms develop into phonograms, in which the sound value (phoneme) of mono- sound & looks (a/b/c) syllabic words is attached to the symbols representing these words. | 2.Scripts | Finally the syllabic script develops into an alphabetic script in which symbols represent single 3.Script phonemes instead of syllables. development | 4.Division Universal sequence from purely pictorial representation (pictograms) to sets of abstracted sound- | 5.Basic unit representing symbols (phonograms). of writing Pictograms convey meaning without intervention of sound values; there may be a symbol meaning ‘town’, | ‘river’ or ‘mountain’ irrespective of what the word for ‘town’, ‘river’ or ‘mountain’ sounds like, and thus 6.Logograms | regardless of any specific language. Such a symbol is named a logogram (pictogram for a specific word). 7.Ideographic The advantage of logograms is their universal applicability – because they are language-independent – but and they have the obvious disadvantage that there must be a separate symbol for every word. logographic scripts | All complete writing systems the world has ever known, do effectively contain both logograms and 8.Syllabic phonograms. As purely pictorial ‘proto-scripts’ develop into ‘scripts’ or writing systems, naturally drawn scripts pictograms are stylised and augmented with drawings for abstract phenomena (hence called ideograms), | 9.Alphabetic and will ultimately contain logograms for all basic words of a specific language. -

The Notion of Syllable Across History, Theories and Analysis

The Notion of Syllable across History, Theories and Analysis The Notion of Syllable across History, Theories and Analysis Edited by Domenico Russo The Notion of Syllable across History, Theories and Analysis Edited by Domenico Russo This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Domenico Russo and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8054-X ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-8054-1 CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................ ix Domenico Russo Part I. The Dawn of the Syllable Chapter One ................................................................................................. 2 The Syllable in a Syntagmatic and Paradigmatic Perspective: The Cuneiform Writing in the II Millennium B.C. in Near East and Anatolian Paola Cotticelli Kurras Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 33 Syllables and Syllabaries: Evidence from Two Aegean Syllabic Scripts Carlo Consani Chapter Three ........................................................................................... -

Pictograms and Visual Cognition

Damian Goidich Professor Diane Zeeuw New Visual Studies April 5, 2011 Pictograms and Visual Cognition Pictograms are a unique addition to the history of our pictorial language. Initially devised as a 20th century solution to the complications created by the globalization of mass transit, communication and travel, their effectiveness at transmitting messages, commands and direction through a distinct set of graphic shapes, symbols and colors has revolutionized how we visually interpret images and communicate on an international scale in the 21st century. Pictograms as a visual form of communication have their roots in ancient civilizations dating back to the fourth millennium BCE. The earliest use of pictograms as a form of communication or “writing” is generally attributed to the Sumerian civilization circa 3500 BCE (Fig. 1). While little is known of the details surrounding their culture, archaeological evidence suggests that their use of cuneiforms was a specialized form of object representation used to record, amongst other things, economic transactions such as the buying and selling of livestock and foodstuffs (Frutiger 119-20). This form of communication through images has continued virtually uninterrupted down through the historical timeline, being well documented in the cultures of Egypt, China, the Middle East, the Mayan and Aztec civilizations of Mesoamerica, and throughout Medieval Europe. The 20th century brought about a tremendous acceleration in the fields of technology, most evident in the invention and proliferation of the automobile which effected both national and international commerce. This led to the development of an extensive grid of roads and highways necessary for the accommodation of the burgeoning mobile culture. -

The Story of Writing: Alphabets, Hieroglyphs and Pictograms Free

FREE THE STORY OF WRITING: ALPHABETS, HIEROGLYPHS AND PICTOGRAMS PDF Andrew Robinson | 232 pages | 01 May 2007 | Thames & Hudson Ltd | 9780500286609 | English | London, United Kingdom Ancient Egypt's cryptic hieroglyphs | Nature A pictogram or pictograph is a symbol representing a concept, object, activity, place or event by illustration. Pictography is a form of writing whereby ideas are transmitted through drawing. It is the basis of cuneiform and hieroglyphs. Early written symbols were based on pictograms pictures which resemble what they signify and ideograms Hieroglyphs and Pictograms which represent ideas. It is commonly believed that pictograms appeared before ideograms. They were used by various ancient cultures all Hieroglyphs and Pictograms the world since around BC and began to develop into logographic writing systems around BC. Pictograms are still in use as the main medium of written communication in some non-literate cultures in Africa, The Americas, and Oceania, and are often used as simple symbols by most contemporary cultures. An ideogram or ideograph is a graphical symbol that represents an idea, rather than a group of letters arranged according to the phonemes of a spoken language, as is done in alphabetic languages. Examples of ideograms include wayfinding signage, such as in airports and other environments where many people may not be familiar with the language of the place they are in, as well as Arabic numerals and mathematical notation, which are used worldwide regardless of how they are pronounced in different languages. The term "ideogram" is commonly used to describe logographic writing systems such as Egyptian hieroglyphs and Chinese characters. However, symbols in logographic systems generally represent words or morphemes rather than pure ideas. -

Essays in Anatolian Onotnastics1

Essays in Anatolian Onotnastics1 A. LEHRMAN I. Hieroglyphic Luwian Taiman YARIRIS (YA+RA/I-RI-SA), THE EARLY first millennium B.C. ruler of Carchemish (modem Jerablus, a Turkish town on Euphrates near the Syrian border), the author of a number of Hieroglyphic Luwian inscriptions glorifying his deeds and members of his family, in the inscription A 15 b, line IV, proudly informs posterity about his proficiency in' various scripts and languages. This fact is extremely interesting per se, since such a conscious attitude towards linguistic matters was not at all common in Yariris' day and age. Unfortunately, the beginning of line IV, where Yariris enumerates the scripts in which he was literate, is damaged, providing us with only four of the toponyms, or rather toponymic adjectives, referring to scripts he claimed to have mastered. The readable part of the text runs as follows: (A 15 b,IV) 1... 1 URBS-si-ya-ti SCRIBA-li-ya-ti su+rali-wali-ni-ti URBS SCRIBA-li-ya-ti-i a-su+rali-REGIO-wali-na-ti URBS SCRIBA-li-ya-ti-i ta-i- ma-ni-ti-ha URBS SCRIBA -li-ti 12-ha-wali-a "LINGUA" -Ia-ti-i-na u + LITUUS-ni-ha wali-mu-u ta-ni-ma-si-na REGIO-ni-si-i-na-a INFANS-ni-na "VIA"- -ha +rali-wali-ta-hi-tas-ti-i CUM-na ARHA -sa-ta DOMINUS-na-ni-i-sa a-mi- i-sa LINGUA-Ia-ti SUPER+rali-a ta-ni-mi-ha- wali-mu 273-wali +rali-pi-na u+LITUUS-na-nu-ta "1...1in the script of the City, the script of Sura, the script of Assyria and the script of Taiman (?). -

Interface Aesthetics Week 8 Signs, Pictograms, and Icons

Interface Aesthetics Week 8 Signs, pictograms, and icons Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 OUTLINE - Semiotics - Building symbols - Pictograms - Icons - Logos Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 INTERFACE AESTHETICS Assignment 5 Design a new pictogram/ logo/icon for: • I School, or • Your school or program (non-I School), or • Your own project Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 Semiotics: The study of signs Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 SIGNS Signified Signifier Sense The physical thing or The representation of The understanding idea that the sign the object, which that an observer gets stands for. could be a word, a from seeing or picture, or a sound. experiencing either the signified or its signifier. Warm, hot, burn, bright, dangerous, etc. Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 Signs - Symbolic - Iconic - Indexical [Charles Sanders Peirce, 1839-1914] Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 SIGNS Symbolic signs Code or rule-following conventions required Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 SIGNS Symbolic signs Language characters, numbers Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 AMBIENT MEDIA Orb [Ambient Devices] Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 AMBIENT MEDIA Orb [Ambient Devices] Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 SIGNS Symbolic signs Abstract visual representations Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 SIGNS Iconic signs An intermediate degree of transparency to the signified object Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 SIGNS Iconic signs Drawings and caricatures Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 SIGNS Iconic signs Metaphors [Jeremijenko , 1995] Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 SIGNS Indexical signs Directly connected to the signified. Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 Indexical signs Natural signs 16 Jason Courtney http://www.perdador.com/f6update/Oc3.html SIGNS Indexical signs Measuring instruments (scale, thermometer, clock) Interface Aesthetics 03/16/09 Indexical signs Countdowns 18 SIGNS Symbolic Iconic Indexical Language Drawings, Measuring characters, caricatures, instruments numbers, metaphors abstract mapping (e.g.