Docib: 3853634

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bombe: Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CURVE/open How I learned to stop worrying and love the Bombe: Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park Smith, C Author post-print (accepted) deposited by Coventry University’s Repository Original citation & hyperlink: Smith, C 2014, 'How I learned to stop worrying and love the Bombe: Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park' History of Science, vol 52, no. 2, pp. 200-222 https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0073275314529861 DOI 10.1177/0073275314529861 ISSN 0073-2753 ESSN 1753-8564 Publisher: Sage Publications Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. This document is the author’s post-print version, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer-review process. Some differences between the published version and this version may remain and you are advised to consult the published version if you wish to cite from it. Mechanising the Information War – Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park Christopher Smith Abstract The Bombe machine was a key device in the cryptanalysis of the ciphers created by the machine system widely employed by the Axis powers during the Second World War – Enigma. -

VISIT to BLETCHLEY PARK

REPORT of STAR GROUP – VISIT to BLETCHLEY PARK It was 8-30 on the damp drizzly Monday morning of 5th October when our intrepid group of bleary-eyed third-agers left Keyworth to visit the former codebreaking and cipher centre at Bletchley Park. As we progressed south along the M1 motorway the weather started to clear and by the time we arrived in Milton Keynes the rain and drizzle had stopped. For me the first stop was a cup of coffee in the Block C Visitor Centre. We moved out of the Visitor Centre and towards the lake. We were told that many a wartime romantic coupling around this beautiful lake had led to marriage. The beautiful Bletchley Park Lake So… Moving on. We visited the Mansion House with it’s curious variety of styles of architecture. The original owners of the estate had travelled abroad extensively and each time they returned home they added an extension in the styles that they visited on their travels. The Mansion House At the Mansion we saw the sets that had been designed for the Film “The Imitation Game.” The attention to detail led one to feel that you were back there in the dark days of WWII. History of The Mansion Captain Ridley's Shooting Party The arrival of ‘Captain Ridley's Shooting Party’ at a mansion house in the Buckinghamshire countryside in late August 1938 was to set the scene for one of the most remarkable stories of World War Two. They had an air of friends enjoying a relaxed weekend together at a country house. -

Inside Russia's Intelligence Agencies

EUROPEAN COUNCIL ON FOREIGN BRIEF POLICY RELATIONS ecfr.eu PUTIN’S HYDRA: INSIDE RUSSIA’S INTELLIGENCE SERVICES Mark Galeotti For his birthday in 2014, Russian President Vladimir Putin was treated to an exhibition of faux Greek friezes showing SUMMARY him in the guise of Hercules. In one, he was slaying the • Russia’s intelligence agencies are engaged in an “hydra of sanctions”.1 active and aggressive campaign in support of the Kremlin’s wider geopolitical agenda. The image of the hydra – a voracious and vicious multi- headed beast, guided by a single mind, and which grows • As well as espionage, Moscow’s “special services” new heads as soon as one is lopped off – crops up frequently conduct active measures aimed at subverting in discussions of Russia’s intelligence and security services. and destabilising European governments, Murdered dissident Alexander Litvinenko and his co-author operations in support of Russian economic Yuri Felshtinsky wrote of the way “the old KGB, like some interests, and attacks on political enemies. multi-headed hydra, split into four new structures” after 1991.2 More recently, a British counterintelligence officer • Moscow has developed an array of overlapping described Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) as and competitive security and spy services. The a hydra because of the way that, for every plot foiled or aim is to encourage risk-taking and multiple operative expelled, more quickly appear. sources, but it also leads to turf wars and a tendency to play to Kremlin prejudices. The West finds itself in a new “hot peace” in which many consider Russia not just as an irritant or challenge, but • While much useful intelligence is collected, as an outright threat. -

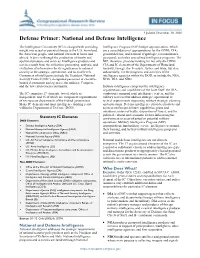

Defense Primer: National and Defense Intelligence

Updated December 30, 2020 Defense Primer: National and Defense Intelligence The Intelligence Community (IC) is charged with providing Intelligence Program (NIP) budget appropriations, which insight into actual or potential threats to the U.S. homeland, are a consolidation of appropriations for the ODNI; CIA; the American people, and national interests at home and general defense; and national cryptologic, reconnaissance, abroad. It does so through the production of timely and geospatial, and other specialized intelligence programs. The apolitical products and services. Intelligence products and NIP, therefore, provides funding for not only the ODNI, services result from the collection, processing, analysis, and CIA and IC elements of the Departments of Homeland evaluation of information for its significance to national Security, Energy, the Treasury, Justice and State, but also, security at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels. substantially, for the programs and activities of the Consumers of intelligence include the President, National intelligence agencies within the DOD, to include the NSA, Security Council (NSC), designated personnel in executive NGA, DIA, and NRO. branch departments and agencies, the military, Congress, and the law enforcement community. Defense intelligence comprises the intelligence organizations and capabilities of the Joint Staff, the DIA, The IC comprises 17 elements, two of which are combatant command joint intelligence centers, and the independent, and 15 of which are component organizations military services that address strategic, operational or of six separate departments of the federal government. tactical requirements supporting military strategy, planning, Many IC elements and most intelligence funding reside and operations. Defense intelligence provides products and within the Department of Defense (DOD). -

Considering the Creation of a Domestic Intelligence Agency in the United States

HOMELAND SECURITY PROGRAM and the INTELLIGENCE POLICY CENTER THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Homeland Security Program RAND Intelligence Policy Center View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. -

Russian Law Enforcement and Internal Security Agencies

September 14, 2020 Russian Law Enforcement and Internal Security Agencies Russia has an extensive internal security system, with Competition frequently leads to arrests and prosecutions, multiple, overlapping, and competitive security agencies often for real or imagined corruption allegations to undercut vying for bureaucratic, political, and economic influence. targeted organizations and senior leadership both Since Vladimir Putin assumed Russia’s leadership, these institutionally and politically. agencies have grown in both size and power, and they have become integral to the security and stability of the Russian Law Enforcement and Internal government. If Putin extends his rule beyond 2024, as is Security Agencies and Heads now legally permissible, these agencies could play a role in (as of September 2020) the leadership succession process and affect the ability of a transitional regime to quell domestic dissent. For Members Ministry of Interior (MVD): Vladimir Kolokoltsev of Congress, understanding the numerous internal security National Guard (Rosgvardiya, FSVNG): Viktor Zolotov agencies in Russia could be helpful in assessing the x Special Purpose Mobile Units (OMON) prospects of regime stability and dynamics of a transition x Special Rapid Response Detachment (SOBR) after Putin leaves office. In addition, Russian security agencies and their personnel have been targeted by U.S. x Interior Troops (VV) sanctions for cyberattacks and human rights abuses. x Kadyrovtsy Overview and Context Federal Security Service (FSB): Alexander Bortnikov -

APPENDIX D Common Abbreviations

ABBREVIATIONS APPENDIX D Common Abbreviations BIS Bureau of Industry and Security (Department of Commerce) BW Biological Weapons or Biological Warfare CBP Customs and Border Protection (Department of Homeland Security) CBRN Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear Weapons CCDC Collection Concepts Development Center CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CIA Central Intelligence Agency CIFA Counterintelligence Field Activity (Department of Defense) CPD Counterproliferation Division (CIA) CTC Counterterrorist Center CW Chemical Weapons or Chemical Warfare D&D Denial and Deception DCI Director of Central Intelligence DCIA Director of Central Intelligence Agency DHS Department of Homeland Security DIA Defense Intelligence Agency DNI Director of National Intelligence DO Directorate of Operations (CIA) DOD Department of Defense DOE Department of Energy DOJ Department of Justice DS&T Directorate of Science and Technology (CIA) FBI Federal Bureau of Investigation FBIS Foreign Broadcast Information Service FIG Field Intelligence Group (FBI) FISA Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act HPSCI House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence HUMINT Human Intelligence IAEA International Atomic Energy Agency IAEC Iraqi Atomic Energy Commission 591 APPENDIX D ICE Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Department of Homeland Security) INC Iraqi National Congress INR Bureau of Intelligence and Research (Department of State) INS Immigration and Naturalization Services IRTPA Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 ISB Intelligence -

THREAT BULLETINS Joint Cybersecurity Advisory on Russian

THREAT BULLETINS Joint Cybersecurity Advisory on Russian GRU Kubernetes Brute Force Campaign TLP:WHITE Jul 06, 2021 On July 1, 2021, the National Security Agency (NSA), Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) released a Joint Cybersecurity Advisory regarding Russian General Staff Main Intelligence Directorate’s (GRU) 85th Main Special Service Center (GTsSS), Unit 26165. The joint advisory outlines Russia’s malicious use of Kubernetes clusters cloaked by various virtual private network (VPN) providers and The Onion Router (TOR) to conduct widespread, distributed, and anonymized brute force access attempts against several government and private sector targets globally. Kubernetes is an open-source system for orchestrating the deployment and management of software containers. This advisory is being shared to prevent a disruption of your network posture as these efforts are almost certainly still ongoing according to the Joint Cybersecurity Advisory. The malicious cyber activity has previously been attributed to threat groups identified as Fancy Bear, APT28, Strontium, and a variety of others by the private sector. A significant amount of malicious activity was directed at organizations using Microsoft Office 365 cloud services in addition to targeting other service providers and on-premises email servers using a variety of different protocols. This brute force capability allows the 85th GTsSS actors to access protected data, including email, and identify valid account credentials. Those credentials may then be used for a variety of purposes, including initial access, persistence, privilege escalation, and defense evasion. The actors have used identified account credentials in conjunction with exploiting publicly known vulnerabilities, such as exploiting Microsoft Exchange servers using CVE 2020-0688 and CVE 2020-17144, for remote code execution and further access to target networks. -

The First Americans the 1941 US Codebreaking Mission to Bletchley Park

United States Cryptologic History The First Americans The 1941 US Codebreaking Mission to Bletchley Park Special series | Volume 12 | 2016 Center for Cryptologic History David J. Sherman is Associate Director for Policy and Records at the National Security Agency. A graduate of Duke University, he holds a doctorate in Slavic Studies from Cornell University, where he taught for three years. He also is a graduate of the CAPSTONE General/Flag Officer Course at the National Defense University, the Intelligence Community Senior Leadership Program, and the Alexander S. Pushkin Institute of the Russian Language in Moscow. He has served as Associate Dean for Academic Programs at the National War College and while there taught courses on strategy, inter- national relations, and intelligence. Among his other government assignments include ones as NSA’s representative to the Office of the Secretary of Defense, as Director for Intelligence Programs at the National Security Council, and on the staff of the National Economic Council. This publication presents a historical perspective for informational and educational purposes, is the result of independent research, and does not necessarily reflect a position of NSA/CSS or any other US government entity. This publication is distributed free by the National Security Agency. If you would like additional copies, please email [email protected] or write to: Center for Cryptologic History National Security Agency 9800 Savage Road, Suite 6886 Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755 Cover: (Top) Navy Department building, with Washington Monument in center distance, 1918 or 1919; (bottom) Bletchley Park mansion, headquarters of UK codebreaking, 1939 UNITED STATES CRYPTOLOGIC HISTORY The First Americans The 1941 US Codebreaking Mission to Bletchley Park David Sherman National Security Agency Center for Cryptologic History 2016 Second Printing Contents Foreword ................................................................................ -

2019 National Intelligence Strategy of the United State

The National Intelligence Strategy of the United States of America IC Vision A Nation made more secure by a fully integrated, agile, resilient, and innovative Intelligence Community that exemplifies America’s values. IC Mission Provide timely, insightful, objective, and relevant intelligence and support to inform national security decisions and to protect our Nation and its interests. This National Intelligence Strategy (NIS) provides the Intelligence Community (IC) with strategic direction from the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) for the next four years. It supports the national security priorities outlined in the National Security Strategy as well as other national strategies. In executing the NIS, all IC activities must be responsive to national security priorities and must comply with the Constitution, applicable laws and statutes, and Congressional oversight requirements. All our activities will be conducted consistent with our guiding principles: We advance our national security, economic strength, and technological superiority by delivering distinctive, timely insights with clarity, objectivity, and independence; we achieve unparalleled access to protected information and exquisite understanding of our adversaries’ intentions and capabilities; we maintain global awareness for strategic warning; and we leverage what others do well, adding unique value for the Nation. IAL-INTE AT LL SP IG O E E N G C E L A A G N E O I N T C A Y N U N A I IC T R E E D S M TATES OF A From the Director of National Intelligence As the Director of National Intelligence, I am fortunate to lead an Intelligence Community (IC) composed of the best and brightest professionals who have committed their careers and their lives to protecting our national security. -

The Poisoned Madeleine: Stasi Files As Evidence and History

Faculty of Information Quarterly Vol 1, No 4 (August 2009) former East German government’s The Poisoned secret police agency, the Stasi. The Stasi records of mass surveillance and Madeleine: Stasi punishment of citizens serve as both a record of the East German people’s Files As Evidence oppression and a vital tool for coming to terms with the communist and History dictatorship in East Germany. Debates about opening versus sealing these files allowed Germans to analyze the disconnect between rights of privacy Rachel E. Beattie and rights of information. The success Rachel E. Beattie, a recent graduate of the laws created to both open and of University of Toronto’s Faculty of restrict the use of the Stasi files can be Information, has an interest in both attributed to the innovative way that Archives and Libraries. She combines these laws were able to these interests with her background in accommodate those who needed English and Film, which she hopes will the information as well as those lead her to a career in an audio-visual concerned about their privacy. archive or library. This paper builds on Further, the whole debate raises many the work of her Film Masters thesis that questions about the power of sensitive dealt with German reunification in documents. In the course of the 1989 and its representation in debate, the veracity of the files was contemporary German film. She is questioned repeatedly, and interested in how the German people individually they are highly suspect. use the tools of information, from However, taken as a group, they build historical records to fictional texts, to a very accurate picture of a repressive deal with their troubled history. -

Churchill's Diplomatic Eavesdropping and Secret Signals Intelligence As

CHURCHILL’S DIPLOMATIC EAVESDROPPING AND SECRET SIGNALS INTELLIGENCE AS AN INSTRUMENT OF BRITISH FOREIGN POLICY, 1941-1944: THE CASE OF TURKEY Submitted for the Degree of Ph.D. Department of History University College London by ROBIN DENNISTON M.A. (Oxon) M.Sc. (Edin) ProQuest Number: 10106668 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10106668 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 2 ABSTRACT Churchill's interest in secret signals intelligence (sigint) is now common knowledge, but his use of intercepted diplomatic telegrams (bjs) in World War Two has only become apparent with the release in 1994 of his regular supply of Ultra, the DIR/C Archive. Churchill proves to have been a voracious reader of diplomatic intercepts from 1941-44, and used them as part of his communication with the Foreign Office. This thesis establishes the value of these intercepts (particularly those Turkey- sourced) in supplying Churchill and the Foreign Office with authentic information on neutrals' response to the war in Europe, and analyses the way Churchill used them.