The First Americans the 1941 US Codebreaking Mission to Bletchley Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To What Extent Did British Advancements in Cryptanalysis During World War II Influence the Development of Computer Technology?

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2016 Apr 28th, 9:00 AM - 10:15 AM To What Extent Did British Advancements in Cryptanalysis During World War II Influence the Development of Computer Technology? Hayley A. LeBlanc Sunset High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y LeBlanc, Hayley A., "To What Extent Did British Advancements in Cryptanalysis During World War II Influence the Development of Computer Technology?" (2016). Young Historians Conference. 1. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2016/oralpres/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. To what extent did British advancements in cryptanalysis during World War 2 influence the development of computer technology? Hayley LeBlanc 1936 words 1 Table of Contents Section A: Plan of Investigation…………………………………………………………………..3 Section B: Summary of Evidence………………………………………………………………....4 Section C: Evaluation of Sources…………………………………………………………………6 Section D: Analysis………………………………………………………………………………..7 Section E: Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………10 Section F: List of Sources………………………………………………………………………..11 Appendix A: Explanation of the Enigma Machine……………………………………….……...13 Appendix B: Glossary of Cryptology Terms.…………………………………………………....16 2 Section A: Plan of Investigation This investigation will focus on the advancements made in the field of computing by British codebreakers working on German ciphers during World War 2 (19391945). -

THE RADAR WAR Forward

THE RADAR WAR by Gerhard Hepcke Translated into English by Hannah Liebmann Forward The backbone of any military operation is the Army. However for an international war, a Navy is essential for the security of the sea and for the resupply of land operations. Both services can only be successful if the Air Force has control over the skies in the areas in which they operate. In the WWI the Air Force had a minor role. Telecommunications was developed during this time and in a few cases it played a decisive role. In WWII radar was able to find and locate the enemy and navigation systems existed that allowed aircraft to operate over friendly and enemy territory without visual aids over long range. This development took place at a breath taking speed from the Ultra High Frequency, UHF to the centimeter wave length. The decisive advantage and superiority for the Air Force or the Navy depended on who had the better radar and UHF technology. 0.0 Aviation Radio and Radar Technology Before World War II From the very beginning radar technology was of great importance for aviation. In spite of this fact, the radar equipment of airplanes before World War II was rather modest compared with the progress achieved during the war. 1.0 Long-Wave to Short-Wave Radiotelegraphy In the beginning, when communication took place only via telegraphy, long- and short-wave transmitting and receiving radios were used. 2.0 VHF Radiotelephony Later VHF radios were added, which made communication without trained radio operators possible. 3.0 On-Board Direction Finding A loop antenna served as a navigational aid for airplanes. -

Edsger Dijkstra: the Man Who Carried Computer Science on His Shoulders

INFERENCE / Vol. 5, No. 3 Edsger Dijkstra The Man Who Carried Computer Science on His Shoulders Krzysztof Apt s it turned out, the train I had taken from dsger dijkstra was born in Rotterdam in 1930. Nijmegen to Eindhoven arrived late. To make He described his father, at one time the president matters worse, I was then unable to find the right of the Dutch Chemical Society, as “an excellent Aoffice in the university building. When I eventually arrived Echemist,” and his mother as “a brilliant mathematician for my appointment, I was more than half an hour behind who had no job.”1 In 1948, Dijkstra achieved remarkable schedule. The professor completely ignored my profuse results when he completed secondary school at the famous apologies and proceeded to take a full hour for the meet- Erasmiaans Gymnasium in Rotterdam. His school diploma ing. It was the first time I met Edsger Wybe Dijkstra. shows that he earned the highest possible grade in no less At the time of our meeting in 1975, Dijkstra was 45 than six out of thirteen subjects. He then enrolled at the years old. The most prestigious award in computer sci- University of Leiden to study physics. ence, the ACM Turing Award, had been conferred on In September 1951, Dijkstra’s father suggested he attend him three years earlier. Almost twenty years his junior, I a three-week course on programming in Cambridge. It knew very little about the field—I had only learned what turned out to be an idea with far-reaching consequences. a flowchart was a couple of weeks earlier. -

The Turing Approach Vs. Lovelace Approach

Connecting the Humanities and the Sciences: Part 2. Two Schools of Thought: The Turing Approach vs. The Lovelace Approach* Walter Isaacson, The Jefferson Lecture, National Endowment for the Humanities, May 12, 2014 That brings us to another historical figure, not nearly as famous, but perhaps she should be: Ada Byron, the Countess of Lovelace, often credited with being, in the 1840s, the first computer programmer. The only legitimate child of the poet Lord Byron, Ada inherited her father’s romantic spirit, a trait that her mother tried to temper by having her tutored in math, as if it were an antidote to poetic imagination. When Ada, at age five, showed a preference for geography, Lady Byron ordered that the subject be replaced by additional arithmetic lessons, and her governess soon proudly reported, “she adds up sums of five or six rows of figures with accuracy.” Despite these efforts, Ada developed some of her father’s propensities. She had an affair as a young teenager with one of her tutors, and when they were caught and the tutor banished, Ada tried to run away from home to be with him. She was a romantic as well as a rationalist. The resulting combination produced in Ada a love for what she took to calling “poetical science,” which linked her rebellious imagination to an enchantment with numbers. For many people, including her father, the rarefied sensibilities of the Romantic Era clashed with the technological excitement of the Industrial Revolution. Lord Byron was a Luddite. Seriously. In his maiden and only speech to the House of Lords, he defended the followers of Nedd Ludd who were rampaging against mechanical weaving machines that were putting artisans out of work. -

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bombe: Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CURVE/open How I learned to stop worrying and love the Bombe: Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park Smith, C Author post-print (accepted) deposited by Coventry University’s Repository Original citation & hyperlink: Smith, C 2014, 'How I learned to stop worrying and love the Bombe: Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park' History of Science, vol 52, no. 2, pp. 200-222 https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0073275314529861 DOI 10.1177/0073275314529861 ISSN 0073-2753 ESSN 1753-8564 Publisher: Sage Publications Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. This document is the author’s post-print version, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer-review process. Some differences between the published version and this version may remain and you are advised to consult the published version if you wish to cite from it. Mechanising the Information War – Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park Christopher Smith Abstract The Bombe machine was a key device in the cryptanalysis of the ciphers created by the machine system widely employed by the Axis powers during the Second World War – Enigma. -

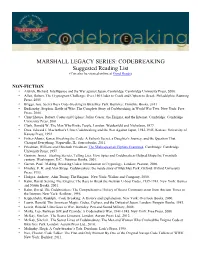

CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can Also Be Viewed Online at Good Reads)

MARSHALL LEGACY SERIES: CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can also be viewed online at Good Reads) NON-FICTION • Aldrich, Richard. Intelligence and the War against Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. • Allen, Robert. The Cryptogram Challenge: Over 150 Codes to Crack and Ciphers to Break. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2005 • Briggs, Asa. Secret Days Code-breaking in Bletchley Park. Barnsley: Frontline Books, 2011 • Budiansky, Stephen. Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War Two. New York: Free Press, 2000. • Churchhouse, Robert. Codes and Ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. • Clark, Ronald W. The Man Who Broke Purple. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1977. • Drea, Edward J. MacArthur's Ultra: Codebreaking and the War Against Japan, 1942-1945. Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 1992. • Fisher-Alaniz, Karen. Breaking the Code: A Father's Secret, a Daughter's Journey, and the Question That Changed Everything. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2011. • Friedman, William and Elizebeth Friedman. The Shakespearian Ciphers Examined. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957. • Gannon, James. Stealing Secrets, Telling Lies: How Spies and Codebreakers Helped Shape the Twentieth century. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2001. • Garrett, Paul. Making, Breaking Codes: Introduction to Cryptology. London: Pearson, 2000. • Hinsley, F. H. and Alan Stripp. Codebreakers: the inside story of Bletchley Park. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. • Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing: The Enigma. New York: Walker and Company, 2000. • Kahn, David. Seizing The Enigma: The Race to Break the German U-boat Codes, 1939-1943. New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 2001. • Kahn, David. The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet. -

The NAMTA Journal

The NAMTA Journal Back To The Future Volume 45. Number 1 May 2021 Molly OʼShaughnessy Jacqui Miller Kimberlee Belcher-Badal Ph.D. Robyn MilosGregory MacDonald Jennifer ShieldsJacquie Maughan Lena WikramaratneAudrey Sillick Gerard Leonard Kathleen Allen Jim RobbinsDeborah Bricker Dr. Maria Montessori Mario M. Montessori A.M. Joosten Mary Black Verschuur Ph.D. John McNamara David Kahn TABLE OF CONTENTS BACK TO THE FUTURE:WHY MONTESSORI STILL MATTERS …………..………….…….7 Molly O’Shaughnessy THE RETURN TO SCIENTIFIC PEDAGOGY: EMBRACING OUR ROOTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES……………………………………………………………………….33 Jacqui Miller and Kimberlee Belcher-Badal Ph.D. IN REMEMBRANCE………………………………..……………..……………………...53 Deborah Bricker TRIBUTE TO ANNETTE HAINES…………………..……………..……………………....56 Robyn Milos TRIBUTE TO KAY BAKER………………………..……………..…………………….... 59 Gregory MacDonald TRIBUTE TO JOEN BETTMANN………………..………………..………………………..62 Jennifer Shields GUIDED BY NATURE…………….…………..………….……..………………………..66 Jacquie Maughan THE CHILD IN THE WORLD OF NATURE…….………..…………………………..69 Lena Wikramaratne SOWING THE SEEDS OF SCIENCE:OUR GIFT TO THE FUTURE…………………...78 Audrey Sillick EXPERIENCES IN NATURE:RESOLUTE SECOND-PLANE DIRECTIONS……….……...88 TOWARD ERDKINDER Gerard Leonard and Kathleen Allen 2 The NAMTA Journal • Vol. 44, No. 1 • Winter 2020 ECOPSYCHOLOGY:HOW IMMERSION IN NATURE AFFECTS YOUR HEALTH……….107 TOWARD ERDKINDER Jim Robbins SILENCE AND LISTENING ……………………..………………...……..………….…….115 Gerard Leonard ABOUT THE IMPORTANCE AND THE NATURE OF THE SILENCE GAME…………………………………..………………...………………….. 117 -

Tyringham Hall Tyringhamtyringham

Tyringham Hall TyringhamTyringham ... Buckinghamshire Hall Tyringham Hall by H. Hobson, March 1890 A magnificent Grade I Listed Soane Georgian Mansion with garden buildings and landscape by Lutyens 1 Tyringham Hall TyringhamTyringham ... Buckinghamshire Hall Central London: 45 miles Olney: 4.5 miles M1 (Junction 14): 5 miles Trains to London Euston from 35 minutes (Milton Keynes) International Airport: 25 miles (Luton) in all about 59.21 ACRES (23.966 HECTARES) Please note: Freehold 37.50 acres (15.18 hectares) Leasehold 21.71 acres (8.786 hectares) 4 Crispin Holborow Nick Ingle Savills London Savills Harpenden Tel: 0207 409 8881 Tel: 01582 465 002 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text. 5 6 The Bridge over the River Ouse The founTain To The fronT elevaTion of The house feaTuring Diana anD apollo 7 TyringhamTyRingham HallHALL SUMMARY Lutyens masterpieces and one of Europe’s largest reflecting pools. Tyringham Hall is a beautiful Grade I listed English stately home The majority of furniture and contents in the house, stable house built by Sir John Soane with gardens and garden buildings by Sir and grounds will be available by separate negotiation. Edwin Lutyens, one of only a handful of country houses that can lay claim to have been worked on by two of England’s greatest architects. SITUATION Tyringham Hall is situated in magnificent parkland setting The 18th century neo-classical villa includes 4 magnificently approximately 4.5 miles south of the picturesque market town of proportioned reception rooms, a kitchen, breakfast room and Olney and 5 miles from Junction 14 of the M1. -

NSA's Efforts to Secure Private-Sector Telecommunications Infrastructure

Under the Radar: NSA’s Efforts to Secure Private-Sector Telecommunications Infrastructure Susan Landau* INTRODUCTION When Google discovered that intruders were accessing certain Gmail ac- counts and stealing intellectual property,1 the company turned to the National Security Agency (NSA) for help in securing its systems. For a company that had faced accusations of violating user privacy, to ask for help from the agency that had been wiretapping Americans without warrants appeared decidedly odd, and Google came under a great deal of criticism. Google had approached a number of federal agencies for help on its problem; press reports focused on the company’s approach to the NSA. Google’s was the sensible approach. Not only was NSA the sole government agency with the necessary expertise to aid the company after its systems had been exploited, it was also the right agency to be doing so. That seems especially ironic in light of the recent revelations by Edward Snowden over the extent of NSA surveillance, including, apparently, Google inter-data-center communications.2 The NSA has always had two functions: the well-known one of signals intelligence, known in the trade as SIGINT, and the lesser known one of communications security or COMSEC. The former became the subject of novels, histories of the agency, and legend. The latter has garnered much less attention. One example of the myriad one could pick is David Kahn’s seminal book on cryptography, The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet.3 It devotes fifty pages to NSA and SIGINT and only ten pages to NSA and COMSEC. -

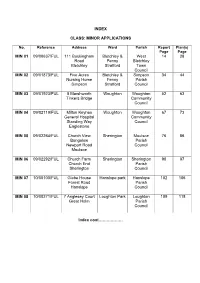

Index Class: Minor Applications Min 01 09/00637

INDEX CLASS: MINOR APPLICATIONS No. Reference Address Ward Parish Report Plan(s) Page Page MIN 01 09/00637/FUL 111 Buckingham Bletchley & West 14 28 Road Fenny Bletchley Bletchley Stratford Town Council MIN 02 09/01873/FUL Five Acres Bletchley & Simpson 34 44 Nursing Home Fenny Parish Simpson Stratford Council MIN 03 09/01923/FUL 8 Marshworth Woughton Woughton 52 63 Tinkers Bridge Community Council MIN 04 09/02119/FUL Milton Keynes Woughton Woughton 67 73 General Hospital Community Standing Way Council Eaglestone MIN 05 09/02264/FUL Church View Sherington Moulsoe 76 86 Bungalow Parish Newport Road Council Moulsoe MIN 06 09/02292/FUL Church Farm Sherington Sherington 90 97 Church End Parish Sherington Council MIN 07 10/00100/FUL Glebe House Hanslope park Hanslope 102 106 Forest Road Parish Hanslope Council MIN 08 10/00271/FUL 7 Anglesey Court Loughton Park Loughton 109 118 Great Holm Parish Council Index cont……………… CLASS: OTHER APPLICATIONS No. Reference Address Ward Parish Report Plan(s) Page Page OTH 01 09/01872/FUL 1 Rose Cottages Wolverton Wolverton & 122 130 Mill End Greenleys Wolverton Mill Town Council OTH 02 09/01907/FUL 6 Twyford Lane Walton park Walton 135 140 Walnut Tree parish Council OTH 03 09/02161/FUL 16 Stanbridge Stony Stony 143 148 Court Stratford Stratford Stony Stratford Town Council OTH 04 09/02217/FUL 220A Wolverton Linford North Great Linford 152 159 Road Parish Blakelands Council OTH 05 10/00117/FUL 98 High Street Olney Olney Town 162 166 Olney Council OTH 06 10/00049/FUL 63 Wolverton Newport Newport 168 174 Road Pagnell North Pagnell Newport Pagnell Town Council OTH 07 10/00056/FUL 24 Sitwell Close Newport Newport 177 182 Newport Pagnell Pagnell North Pagnell Town Council CLASS: OTHER APPLICATIONS – HOUSES IN MULTIPLE OCCUPATION No. -

ANNEX a to ITEM 8 Central Bletchley Regeneration Strategy

ANNEX A TO ITEM 8 Central Bletchley Regeneration Strategy - Executive Summary Key Principles Use & activities Currently, Bletchley town centre remains comparatively unattractive to property developers and occupiers. The environment is out dated and creates a negative image for the town and its communities; reducing its ability to attract significant investment. This in turn has led to less people using the centre, creating lower expenditure and investment within the town. Bletchley needs to move forward from its existing primary role as a discount and value retailing location and strengthen its role as the second centre for the city of Milton Keynes. The challenge for the Framework is to create the conditions for Bletchley to promote itself as a place quite distinctive from the rest of Milton Keynes, yet complementary to CMK in its scale and richness of uses and activities. Achieving this will require the town to increase the diversity, quality and range of uses and activities offered in the centre. The Framework promotes the growth of key uses and activities including diversified mixed-use development; new retailing opportunities; residential town centre living; an evening economy with a range of restaurants, bars and cafes; employment opportunities to stimulate appropriate town centre employment; a new leisure centre and cultural and civic uses to fulfil Central Bletchley’s role as the city’s second centre. Access and Movement Pedestrian movement and cycle access throughout Central Bletchley is severely constrained by highly engineered road infrastructure, the railway station and sidings and through severance of Queensway caused by the Brunel Centre. Congested double roundabouts at Watling Street and Buckingham Road offer poor arrival points into the town and restrict car access into Bletchley. -

STEM DISCOVERY: LONDON 8 Or 11 Days | England

® Learn more at Tour s for Girl Scouts eftours.com/girlscouts or call 800-457-9023 STEM DISCOVERY: LONDON 8 or 11 days | England Let STEM be your guide during your exploration of London. Uncover secret messages at Bletchley Park, the birthplace of modern information technology. Practice your sleuthing skills during a CSI-inspired forensics workshop. And plant your feet on two different hemispheres at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, with the English capital as your backdrop. Make a special visit to Pax Lodge in Hampstead where you will participate in unique Girl Scout programming. EVERYTHING YOU GET: Full-time Tour Director Sightseeing: 2 sightseeing tours led by expert, licensed local guides (3 with extension) Entrances: London Eye, Science Museum/Natural History Museum, Tower of London, theater show, National Museum of Computing, Thames River Cruise, Royal Observatory; with extension: Louvre; Notre-Dame Cathedral Experiential learning: Forensics workshop, Stonehenge activities, Bletchley Park interactive workshop WAGGGS Centre visit: Pax Lodge All of the details are covered: Round-trip flights on major carriers; Comfortable motorcoach; Eurostar high-speed train with extension; 7 overnight stays in hotels with private bathrooms (9 with extension); European breakfast and dinner daily DAY 1: FLY OVERNIGHT TO ENGLAND DAY 2: LONDON – Meet your Tour Director at the airport in London, a city that has become one of the world’s great melting pots while maintaining a distinct character that’s all its own. – Take a walking tour of the city and ride the London Eye, a large Ferris wheel along the River Thames that offers panoramic views of the city.