An Introduction to Practice from a Soto-Rinzai Dialogue with Daigaku

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Path to Bodhidharma

The Path to Bodhidharma The teachings of Shodo Harada Roshi 1 Table of Contents Preface................................................................................................ 3 Bodhidharma’s Outline of Practice ..................................................... 5 Zazen ................................................................................................ 52 Hakuin and His Song of Zazen ......................................................... 71 Sesshin ........................................................................................... 100 Enlightenment ................................................................................. 115 Work and Society ............................................................................ 125 Kobe, January 1995 ........................................................................ 139 Questions and Answers ................................................................... 148 Glossary .......................................................................................... 174 2 Preface Shodo Harada, the abbot of Sogenji, a three-hundred-year-old Rinzai Zen Temple in Okayama, Japan, is the Dharma heir of Yamada Mumon Roshi (1890-1988), one of the great Rinzai masters of the twentieth century. Harada Roshi offers his teachings to everyone, ordained monks and laypeople, men and women, young and old, from all parts of the world. His students have begun more than a dozen affiliated Zen groups, known as One Drop Zendos, in the United States, Europe, and Asia. The material -

Reflections on Zen and Ethics Jan Van Bragt Introduction Quite a Few

Reflections on Zen and Ethics1 Jan Van Bragt Introduction Quite a few years ago already, the fast-growing Zen world in the United States was shocked by the news of scandals discovered in some U.S. Zen halls, sexual and financial abuses committed by Zen Masters. I have forgotten all the details already, but the facts confronted us all with an intriguing question, namely: How is it possible that Zen Masters (Rôshis) – people who are supposed to be enlightened – commit such unethical, immoral acts? From the Zen world two. rather contradictory, answers were soon heard. One, (the answer explicitly voiced by Abe Masao): “A Zen Master who commits such acts proves thereby that he is not enlightened.” The presupposition here seems to be that transcendental wisdom is intrinsically linked to morality and directs the subject to spontaneously lead a highly ethical life. – The problem here is only that doubt is thrown at the system of attestation of the enlightenment of the disciple by the master (inka). The second answer is rather the opposite of the first: “Enlightenment has nothing to do with ethics,” and further: “Zen has nothing to do with ethics.” I must confess that I never heard this answer explicitly formulated, in all its definiteness, by any of my Zen friends. The nearest thing I ever heard directly was a statement made, at the 1991 meeting of the Japan Society for Buddhist-Christian Studies, by Nishimura Eshin, presently president of Hanazono University at Kyoto: “Zen has nothing to do with social engagement.” For the sake of possible later -

A Departure for Returning to Sabha: a Study of Koan Practice of Silence Jea Sophia Oh West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

West Chester University Digital Commons @ West Chester University Philosophy College of Arts & Humanities 12-2017 A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence Jea Sophia Oh West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/phil_facpub Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons Recommended Citation Oh, J. S. (2017). A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence. International Journal of Dharma Studies, 5(12) http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40613-017-0059-7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Humanities at Digital Commons @ West Chester University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ West Chester University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Oh International Journal of Dharma Studies (2017) 5:12 International Journal of DOI 10.1186/s40613-017-0059-7 Dharma Studies RESEARCH Open Access A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence Jea Sophia Oh Correspondence: [email protected] West Chester University of Abstract Pennsylvania, 700 S High St. AND 108D, West Chester, PA 19383, USA This paper deals with koan practice of silence through analyzing the Korean Zen Buddhist film, Why Has Boddhidharma Left for the East? (Bae, Yong-Kyun, Why Has Bodhidharma Left for the East? 1989). This paper follows Kibong's path along with the Buddha's journey of 1) departure, 2) journey in the middle way, and 3) returning with a particular focus on koan practice of silence as the transformative element of enlightenment. -

ZEN at WAR War and Peace Library SERIES EDITOR: MARK SELDEN

ZEN AT WAR War and Peace Library SERIES EDITOR: MARK SELDEN Drugs, Oil, and War: The United States in Afghanistan, Colombia, and Indochina BY PETER DALE SCOTT War and State Terrorism: The United States, Japan, and the Asia-Pacific in the Long Twentieth Century EDITED BY MARK SELDEN AND ALVIN Y. So Bitter Flowers, Sweet Flowers: East Timor, Indonesia, and the World Community EDITED BY RICHARD TANTER, MARK SELDEN, AND STEPHEN R. SHALOM Politics and the Past: On Repairing Historical Injustices EDITED BY JOHN TORPEY Biological Warfare and Disarmament: New Problems/New Perspectives EDITED BY SUSAN WRIGHT BRIAN DAIZEN VICTORIA ZEN AT WAR Second Edition ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Oxford ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Published in the United States of America by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowmanlittlefield.com P.O. Box 317, Oxford OX2 9RU, UK Copyright © 2006 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. Cover image: Zen monks at Eiheiji, one of the two head monasteries of the Sōtō Zen sect, undergoing mandatory military training shortly after the passage of the National Mobilization Law in March 1938. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Victoria, Brian Daizen, 1939– Zen at war / Brian Daizen Victoria.—2nd ed. -

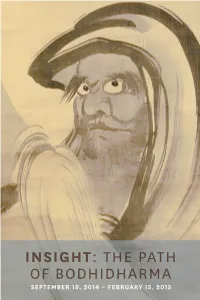

Insight: the Path of Bodhidharma

INSIGHT: THE PATH OF BODHIDHARMA SEPTEMBER 19, 2014 – FEBRUARY 15, 2015 Credited with introducing Chan (Zen in Japanese) Buddhism to China in the sixth century, the Indian monk Bodhidharma (known as Daruma in Japan) has become a well-known subject in Buddhist art. As Chan Buddhism gained popularity, various legends associated with the Chan patriarch evolved, and artists began to depict those legends alongside his conventional portraits. Traditional depictions of Bodhidharma were executed in ink monochrome with free, expressive brush strokes, alluding to his teaching on the spontaneous nature of reaching enlightenment through meditation. During the Edo period (1603-1868) in Japan, the depiction of this pious monk’s stern expression went through a radical change as he was often paired with a courtesan of the pleasure quarters—a parody to expose the hypocrisy of society. Today, Bodhidharma is still widely represented both in fine art and as a pop culture icon of good luck. Through an array of objects from paintings and sculptures to decorative objects and toys, Insight: The Path of Bodhidharma illustrates the visual and conceptual shift in depictions of this religious figure from the 17th century through today. BODHIDHARMA AS CHAN PATRIARCH One of the most common portrayals of Bodhidharma is a bust portrait revealing only the upper half of his body. In a three- quarter profile, he was frequently depicted in ways that emphasize his non-East Asian heritage and iconoclastic persona with large glaring eyes, a prominent nose and beard—sometimes an earring and red hooded robe. The primary goal of Bodhidharma’s teaching is to reach personal enlightenment through meditation that clears one’s mind from distracting thoughts and worldly concerns. -

Hakuin on Kensho: the Four Ways of Knowing/Edited with Commentary by Albert Low.—1St Ed

ABOUT THE BOOK Kensho is the Zen experience of waking up to one’s own true nature—of understanding oneself to be not different from the Buddha-nature that pervades all existence. The Japanese Zen Master Hakuin (1689–1769) considered the experience to be essential. In his autobiography he says: “Anyone who would call himself a member of the Zen family must first achieve kensho- realization of the Buddha’s way. If a person who has not achieved kensho says he is a follower of Zen, he is an outrageous fraud. A swindler pure and simple.” Hakuin’s short text on kensho, “Four Ways of Knowing of an Awakened Person,” is a little-known Zen classic. The “four ways” he describes include the way of knowing of the Great Perfect Mirror, the way of knowing equality, the way of knowing by differentiation, and the way of the perfection of action. Rather than simply being methods for “checking” for enlightenment in oneself, these ways ultimately exemplify Zen practice. Albert Low has provided careful, line-by-line commentary for the text that illuminates its profound wisdom and makes it an inspiration for deeper spiritual practice. ALBERT LOW holds degrees in philosophy and psychology, and was for many years a management consultant, lecturing widely on organizational dynamics. He studied Zen under Roshi Philip Kapleau, author of The Three Pillars of Zen, receiving transmission as a teacher in 1986. He is currently director and guiding teacher of the Montreal Zen Centre. He is the author of several books, including Zen and Creative Management and The Iron Cow of Zen. -

Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit Name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit Dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist Influences (C

7/11/2014 Zen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen is a school of Mahayana Buddhism[note 1] that Zen developed in China during the 6th century as Chán. From China, Zen spread south to Vietnam, northeast to Korea and Chinese name east to Japan.[2] Simplified Chinese 禅 Traditional Chinese 禪 The word Zen is derived from the Japanese pronunciation of the Middle Chinese word 禪 (dʑjen) (pinyin: Chán), which in Transcriptions turn is derived from the Sanskrit word dhyāna,[3] which can Mandarin be approximately translated as "absorption" or "meditative Hanyu Pinyin Chán state".[4] Cantonese Zen emphasizes insight into Buddha-nature and the personal Jyutping Sim4 expression of this insight in daily life, especially for the benefit Middle Chinese [5][6] of others. As such, it de-emphasizes mere knowledge of Middle Chinese dʑjen sutras and doctrine[7][8] and favors direct understanding Vietnamese name through zazen and interaction with an accomplished Vietnamese Thiền teacher.[9] Korean name The teachings of Zen include various sources of Mahāyāna Hangul 선 thought, especially Yogācāra, the Tathāgatagarbha Sutras and Huayan, with their emphasis on Buddha-nature, totality, Hanja 禪 and the Bodhisattva-ideal.[10][11] The Prajñāpāramitā Transcriptions literature[12] and, to a lesser extent, Madhyamaka have also Revised Romanization Seon been influential. Japanese name Kanji 禅 Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist influences (c. 200- 500) 1.3 Legendary or Proto-Chán - Six Patriarchs (c. 500-600) 1.4 Early Chán - Tang Dynasty (c. -

Omori Sogen the Art of a Zen Master

Omori Sogen The Art of a Zen Master Omori Roshi and the ogane (large temple bell) at Daihonzan Chozen-ji, Honolulu, 1982. Omori Sogen The Art of a Zen Master Hosokawa Dogen First published in 1999 by Kegan Paul International This edition first published in 2011 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © The Institute of Zen Studies 1999 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 10: 0–7103–0588–5 (hbk) ISBN 13: 978–0–7103–0588–6 (hbk) Publisher’s Note The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. The publisher has made every effort to contact original copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace. Dedicated to my parents Contents Acknowledgements Introduction Part I - The Life of Omori Sogen Chapter 1 Shugyo: 1904–1934 Chapter 2 Renma: 1934–1945 Chapter 3 Gogo no Shugyo: 1945–1994 Part II - The Three Ways Chapter 4 Zen and Budo Chapter 5 Practical Zen Chapter 6 Teisho: The World of the Absolute Present Chapter 7 Zen and the Fine Arts Appendices Books by Omori Sogen Endnotes Index Acknowledgments Many people helped me to write this book, and I would like to thank them all. -

Soto Zen: an Introduction to Zazen

SOT¯ O¯ ZEN An Introduction to Zazen SOT¯ O¯ ZEN: An Introduction to Zazen Edited by: S¯ot¯o Zen Buddhism International Center Published by: SOTOSHU SHUMUCHO 2-5-2, Shiba, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-8544, Japan Tel: +81-3-3454-5411 Fax: +81-3-3454-5423 URL: http://global.sotozen-net.or.jp/ First printing: 2002 NinthFifteenth printing: printing: 20122017 © 2002 by SOTOSHU SHUMUCHO. All rights reserved. Printed in Japan Contents Part I. Practice of Zazen....................................................7 1. A Path of Just Sitting: Zazen as the Practice of the Bodhisattva Way 9 2. How to Do Zazen 25 3. Manners in the Zend¯o 36 Part II. An Introduction to S¯ot¯o Zen .............................47 1. History and Teachings of S¯ot¯o Zen 49 2. Texts on Zazen 69 Fukan Zazengi 69 Sh¯ob¯ogenz¯o Bend¯owa 72 Sh¯ob¯ogenz¯o Zuimonki 81 Zazen Y¯ojinki 87 J¯uniji-h¯ogo 93 Appendixes.......................................................................99 Takkesa ge (Robe Verse) 101 Kaiky¯o ge (Sutra-Opening Verse) 101 Shigu seigan mon (Four Vows) 101 Hannya shingy¯o (Heart Sutra) 101 Fuek¯o (Universal Transference of Merit) 102 Part I Practice of Zazen A Path of Just Sitting: Zazen as the 1 Practice of the Bodhisattva Way Shohaku Okumura A Personal Reflection on Zazen Practice in Modern Times Problems we are facing The 20th century was scarred by two World Wars, a Cold War between powerful nations, and countless regional conflicts of great violence. Millions were killed, and millions more displaced from their homes. All the developed nations were involved in these wars and conflicts. -

Why Did Bodhidharma Go to the East? Buddhism's Struggle with The

Why Did Bodhidharma Go to the East? Buddhism’s Struggle with the Mind in the World If someone asks the meaning of Bodhidharma coming from the West, It is that the handle of a wooden ladle is long, and the mountain torrents run deep; If you want to know the boundless meaning of this, Wait for the wind blowing in the pines to drown out the sound of koto strings. [Koan 18, tr Heine] This question—why did Bodhidharma come from the West?—is ubiquitous in Chinese Ch’an Buddhist literature. Though some see it as an arbitrary question intended merely as an opener to obscure puzzles, I think it represents a genuine intellectual puzzle: Why did Bodhidharma come from the West—that is, from India? Why couldn’t China with its rich literary and philosophical tradition have given rise to Buddhism? We will approach that question, but I prefer to do so backwards. I want to ask instead, “why was it so fortuitous for the development of Buddhist philosophy that Bodhidharma went East? I will argue that by doing so he gave a trajectory to Buddhist thought about the mind and knowledge that allows certain issues that are obscure in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, despite their centrality to the Buddhist critique of Indian orthodoxy, to come into sharper relief, and hence to complete a project begun, but not completable, in that Indo-European context. 1. China and India on mind and world Why did Bodhidharma go to China? This koan is an old one, and I am sure that the answer I will give would disturb even the most realized roshi. -

Karma and the Animal Realm Envisioned Through an Early Yogācāra Lens

Article Becoming Animal: Karma and the Animal Realm Envisioned through an Early Yogācāra Lens Daniel M. Stuart Department of Religious Studies, University of South Carolina, Rutledge College, Columbia, SC 29208, USA; [email protected] Received: 24 April 2019; Accepted: 28 May 2019; Published: 1 June 2019 Abstract: In an early discourse from the Saṃyuttanikāya, the Buddha states: “I do not see any other order of living beings so diversified as those in the animal realm. Even those beings in the animal realm have been diversified by the mind, yet the mind is even more diverse than those beings in the animal realm.” This paper explores how this key early Buddhist idea gets elaborated in various layers of Buddhist discourse during a millennium of historical development. I focus in particular on a middle period Buddhist sūtra, the Saddharmasmṛtyupasthānasūtra, which serves as a bridge between early Buddhist theories of mind and karma, and later more developed theories. This third- century South Asian Buddhist Sanskrit text on meditation practice, karma theory, and cosmology psychologizes animal behavior and places it on a spectrum with the behavior of humans and divine beings. It allows for an exploration of the conceptual interstices of Buddhist philosophy of mind and contemporary theories of embodied cognition. Exploring animal embodiments—and their karmic limitations—becomes a means to exploring all beings, an exploration that can’t be separated from the human mind among beings. Keywords: Buddhism; contemplative practice; mind; cognition; embodiment; the animal realm (tiryaggati); karma; yogācāra; Saddharmasmṛtyupasthānasūtra 1. Introduction In his 2011 book Becoming Animal, David Abram notes a key issue in the field of philosophy of mind, an implication of the emergent full-blown physicalism of the modern scientific materialist episteme. -

Prayer Beads in Japanese Soto Sect

4 Prayer Beads in Japanese Sōtō Zen Michaela Mross WHen a lay parishioner visits a Buddhist temple, he or she usually car- ries a Buddhist rosary.1 It marks a parishioner versus the occasional visi- tor and is considered a necessary item of proper attire. For most Japanese, not wearing a rosary when putting the hands in prayer or reverence seems to be improper.2 Likewise, the official webpage of the Sōtō Zen school instructs lay followers to not forget prayer beads when attending funerals or memorial services. Parishioners should further put a rosary on the lowest shelf of their home altar, ready to be used during prayers.3 Also, the members of the choirs singing Buddhist hymns at Sōtō tem- ples wear short rosaries while singing and playing a bell. Thus, prayer beads serve “as sources of identification,” to borrow John Kieschnick’s words.4 The rosary is an especially interesting object because— besides the robe or o- kesa— “prayer beads are kept closer to the practitioner than any other ritual object. They become physical evidence of faith, devotion, and practice.”5 In contrast to Tendai, Shingon, or Pure Land clerics, Sōtō clerics rarely use prayer beads in ritual settings. Moreover, images of Zen masters usu- ally do not depict monks or nuns holding prayer beads; instead, a fly-whisk or another kind of staff signifies their status as a Zen cleric. Therefore, Buddhist rosaries are typically not associated with Zen. Nevertheless, prayer beads have been used for various purposes in the Sōtō school as well. This chapter aims to illuminate some of the functions and interpre- tations of the rosary in Japanese Sōtō Zen.