Bodhidharma and Peace of Mind Teisho by Rafe Martin, Endless Path Zendo, October 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Path to Bodhidharma

The Path to Bodhidharma The teachings of Shodo Harada Roshi 1 Table of Contents Preface................................................................................................ 3 Bodhidharma’s Outline of Practice ..................................................... 5 Zazen ................................................................................................ 52 Hakuin and His Song of Zazen ......................................................... 71 Sesshin ........................................................................................... 100 Enlightenment ................................................................................. 115 Work and Society ............................................................................ 125 Kobe, January 1995 ........................................................................ 139 Questions and Answers ................................................................... 148 Glossary .......................................................................................... 174 2 Preface Shodo Harada, the abbot of Sogenji, a three-hundred-year-old Rinzai Zen Temple in Okayama, Japan, is the Dharma heir of Yamada Mumon Roshi (1890-1988), one of the great Rinzai masters of the twentieth century. Harada Roshi offers his teachings to everyone, ordained monks and laypeople, men and women, young and old, from all parts of the world. His students have begun more than a dozen affiliated Zen groups, known as One Drop Zendos, in the United States, Europe, and Asia. The material -

PUBLICATION of SAN FRANCISCO ZEN CENTER Vol. XXXVI No. 1 Spring I Summer 2002 CONTENTS

PUBLICATION OF SAN FRANCISCO ZEN CENTER Vol. XXXVI No. 1 Spring I Summer 2002 CONTENTS TALKS 3 The Gift of Zazen BY Shunryu Suzuki-roshi 16 Practice On and Off the Cushion BY Anna Thom 20 The World Is Vast and Wide BY Gretel Ehrlich 36 An Appropriate Response BY Abbess Linda Ruth Cutts POETRY AND ART 4 Kannon in Waves BY Dan Welch (See also front cover and pages 9 and 46) 5 Like Water BY Sojun Mel Weitsman 24 Study Hall BY Zenshin Philip Whalen NEWS AND FEATURES 8 orman Fischer Revisited AN INTERVIEW 11 An Interview with Annie Somerville, Executive Chef of Greens 25 Projections on an Empty Screen BY Michael Wenger 27 Sangha-e! 28 Through a Glass, Darkly BY Alan Senauke 42 'Treasurer's Report on Fiscal Year 2002 DY Kokai Roberts 2 covet WNO eru 111 -ASSl\ll\tll.,,. o..N WEICH The Gi~ of Zazen Shunryu Suzuki Roshi December 14, 1967-Los Altos, California JAM STILL STUDYING to find out what our way is. Recently I reached the conclusion that there is no Buddhism or Zen or anythjng. When I was preparing for the evening lecture in San Francisco yesterday, I tried to find something to talk about, but I couldn't; then I thought of the story 1 was told in Obun Festival when I was young. The story is about water and the people in Hell Although they have water, the people in hell cannot drink it because the water burns like fire or it looks like blood, so they cannot drink it. -

On Lay Practice Within North American Soto Zen James Ishmael Ford 5 February 2018 Blue Cliff Zen Sangha Costa Mesa, California L

On Lay Practice Within North American Soto Zen James Ishmael Ford 5 February 2018 Blue Cliff Zen Sangha Costa Mesa, California Last week I posted on my Monkey Mind blog an essay I titled Soto Zen Buddhism in North America: Some Random Notes From a Work in Progress. There I wrote, along with a couple of small digressions and additions I add for this talk: Probably the most important thing here (within our North American Zen and particularly our North American Soto Zen) has been the rise in the importance of lay practice. My sense is that the Japanese hierarchy pretty close to completely have missed this as something important. And, even within the convert Soto ordained community, a type of clericalism that is a sense that only clerical practice is important exists that has also blinded many to this reality. That reality is how Zen practice belongs to all of us, whatever our condition in life, whether ordained, or lay. Now, this clerical bias comes to us honestly enough. Zen within East Asia is project for the ordained only. But, while that is an historical fact, it is very much a problem here. Actually a profound problem here. Throughout Asia the disciplines of Zen have largely been the province of the ordained, whether traditional Vinaya monastics or Japanese and Korean non-celibate priests. This has been particularly so with Japanese Soto Zen, where the myth and history of Dharma transmission has been collapsed into the normative ordination model. Here I feel it needful to note this is not normative in any other Zen context. -

A Departure for Returning to Sabha: a Study of Koan Practice of Silence Jea Sophia Oh West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

West Chester University Digital Commons @ West Chester University Philosophy College of Arts & Humanities 12-2017 A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence Jea Sophia Oh West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/phil_facpub Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons Recommended Citation Oh, J. S. (2017). A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence. International Journal of Dharma Studies, 5(12) http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40613-017-0059-7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Humanities at Digital Commons @ West Chester University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ West Chester University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Oh International Journal of Dharma Studies (2017) 5:12 International Journal of DOI 10.1186/s40613-017-0059-7 Dharma Studies RESEARCH Open Access A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence Jea Sophia Oh Correspondence: [email protected] West Chester University of Abstract Pennsylvania, 700 S High St. AND 108D, West Chester, PA 19383, USA This paper deals with koan practice of silence through analyzing the Korean Zen Buddhist film, Why Has Boddhidharma Left for the East? (Bae, Yong-Kyun, Why Has Bodhidharma Left for the East? 1989). This paper follows Kibong's path along with the Buddha's journey of 1) departure, 2) journey in the middle way, and 3) returning with a particular focus on koan practice of silence as the transformative element of enlightenment. -

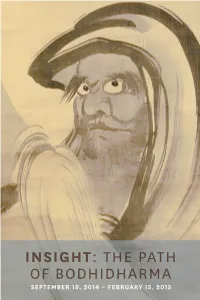

Insight: the Path of Bodhidharma

INSIGHT: THE PATH OF BODHIDHARMA SEPTEMBER 19, 2014 – FEBRUARY 15, 2015 Credited with introducing Chan (Zen in Japanese) Buddhism to China in the sixth century, the Indian monk Bodhidharma (known as Daruma in Japan) has become a well-known subject in Buddhist art. As Chan Buddhism gained popularity, various legends associated with the Chan patriarch evolved, and artists began to depict those legends alongside his conventional portraits. Traditional depictions of Bodhidharma were executed in ink monochrome with free, expressive brush strokes, alluding to his teaching on the spontaneous nature of reaching enlightenment through meditation. During the Edo period (1603-1868) in Japan, the depiction of this pious monk’s stern expression went through a radical change as he was often paired with a courtesan of the pleasure quarters—a parody to expose the hypocrisy of society. Today, Bodhidharma is still widely represented both in fine art and as a pop culture icon of good luck. Through an array of objects from paintings and sculptures to decorative objects and toys, Insight: The Path of Bodhidharma illustrates the visual and conceptual shift in depictions of this religious figure from the 17th century through today. BODHIDHARMA AS CHAN PATRIARCH One of the most common portrayals of Bodhidharma is a bust portrait revealing only the upper half of his body. In a three- quarter profile, he was frequently depicted in ways that emphasize his non-East Asian heritage and iconoclastic persona with large glaring eyes, a prominent nose and beard—sometimes an earring and red hooded robe. The primary goal of Bodhidharma’s teaching is to reach personal enlightenment through meditation that clears one’s mind from distracting thoughts and worldly concerns. -

Hakuin on Kensho: the Four Ways of Knowing/Edited with Commentary by Albert Low.—1St Ed

ABOUT THE BOOK Kensho is the Zen experience of waking up to one’s own true nature—of understanding oneself to be not different from the Buddha-nature that pervades all existence. The Japanese Zen Master Hakuin (1689–1769) considered the experience to be essential. In his autobiography he says: “Anyone who would call himself a member of the Zen family must first achieve kensho- realization of the Buddha’s way. If a person who has not achieved kensho says he is a follower of Zen, he is an outrageous fraud. A swindler pure and simple.” Hakuin’s short text on kensho, “Four Ways of Knowing of an Awakened Person,” is a little-known Zen classic. The “four ways” he describes include the way of knowing of the Great Perfect Mirror, the way of knowing equality, the way of knowing by differentiation, and the way of the perfection of action. Rather than simply being methods for “checking” for enlightenment in oneself, these ways ultimately exemplify Zen practice. Albert Low has provided careful, line-by-line commentary for the text that illuminates its profound wisdom and makes it an inspiration for deeper spiritual practice. ALBERT LOW holds degrees in philosophy and psychology, and was for many years a management consultant, lecturing widely on organizational dynamics. He studied Zen under Roshi Philip Kapleau, author of The Three Pillars of Zen, receiving transmission as a teacher in 1986. He is currently director and guiding teacher of the Montreal Zen Centre. He is the author of several books, including Zen and Creative Management and The Iron Cow of Zen. -

Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit Name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit Dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist Influences (C

7/11/2014 Zen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen is a school of Mahayana Buddhism[note 1] that Zen developed in China during the 6th century as Chán. From China, Zen spread south to Vietnam, northeast to Korea and Chinese name east to Japan.[2] Simplified Chinese 禅 Traditional Chinese 禪 The word Zen is derived from the Japanese pronunciation of the Middle Chinese word 禪 (dʑjen) (pinyin: Chán), which in Transcriptions turn is derived from the Sanskrit word dhyāna,[3] which can Mandarin be approximately translated as "absorption" or "meditative Hanyu Pinyin Chán state".[4] Cantonese Zen emphasizes insight into Buddha-nature and the personal Jyutping Sim4 expression of this insight in daily life, especially for the benefit Middle Chinese [5][6] of others. As such, it de-emphasizes mere knowledge of Middle Chinese dʑjen sutras and doctrine[7][8] and favors direct understanding Vietnamese name through zazen and interaction with an accomplished Vietnamese Thiền teacher.[9] Korean name The teachings of Zen include various sources of Mahāyāna Hangul 선 thought, especially Yogācāra, the Tathāgatagarbha Sutras and Huayan, with their emphasis on Buddha-nature, totality, Hanja 禪 and the Bodhisattva-ideal.[10][11] The Prajñāpāramitā Transcriptions literature[12] and, to a lesser extent, Madhyamaka have also Revised Romanization Seon been influential. Japanese name Kanji 禅 Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist influences (c. 200- 500) 1.3 Legendary or Proto-Chán - Six Patriarchs (c. 500-600) 1.4 Early Chán - Tang Dynasty (c. -

The Zen Koan; Its History and Use in Rinzai

NUNC COCNOSCO EX PARTE TRENT UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation https://archive.org/details/zenkoanitshistorOOOOmiur THE ZEN KOAN THE ZEN KOAN ITS HISTORY AND USE IN RINZAI ZEN ISSHU MIURA RUTH FULLER SASAKI With Reproductions of Ten Drawings by Hakuin Ekaku A HELEN AND KURT WOLFF BOOK HARCOURT, BRACE & WORLD, INC., NEW YORK V ArS) ' Copyright © 1965 by Ruth Fuller Sasaki All rights reserved First edition Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 65-19104 Printed in Japan CONTENTS f Foreword . PART ONE The History of the Koan in Rinzai (Un-chi) Zen by Ruth F. Sasaki I. The Koan in Chinese Zen. 3 II. The Koan in Japanese Zen. 17 PART TWO Koan Study in Rinzai Zen by Isshu Miura Roshi, translated from the Japanese by Ruth F. Sasaki I. The Four Vows. 35 II. Seeing into One’s Own Nature (i) . 37 vii 8S988 III. Seeing into One’s Own Nature (2) . 41 IV. The Hosshin and Kikan Koans. 46 V. The Gonsen Koans . 52 VI. The Nanto Koans. 57 VII. The Goi Koans. 62 VIII. The Commandments. 73 PART THREE Selections from A Zen Phrase Anthology translated by Ruth F. Sasaki. 79 Drawings by Hakuin Ekaku.123 Index.147 viii FOREWORD The First Zen Institute of America, founded in New York City in 1930 by the late Sasaki Sokei-an Roshi for the purpose of instructing American students of Zen in the traditional manner, celebrated its twenty-fifth anniversary on February 15, 1955. To commemorate that event it invited Miura Isshu Roshi of the Koon-ji, a monastery belonging to the Nanzen-ji branch of Rinzai Zen and situated not far from Tokyo, to come to New York and give a series of talks at the Institute on the subject of koan study, the study which is basic for monks and laymen in traditional, transmitted Rinzai Zen. -

A Beginner's Guide to Meditation

ABOUT THE BOOK As countless meditators have learned firsthand, meditation practice can positively transform the way we see and experience our lives. This practical, accessible guide to the fundamentals of Buddhist meditation introduces you to the practice, explains how it is approached in the main schools of Buddhism, and offers advice and inspiration from Buddhism’s most renowned and effective meditation teachers, including Pema Chödrön, Thich Nhat Hanh, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, Sharon Salzberg, Norman Fischer, Ajahn Chah, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, Sylvia Boorstein, Noah Levine, Judy Lief, and many others. Topics include how to build excitement and energy to start a meditation routine and keep it going, setting up a meditation space, working with and through boredom, what to look for when seeking others to meditate with, how to know when it’s time to try doing a formal meditation retreat, how to bring the practice “off the cushion” with walking meditation and other practices, and much more. ROD MEADE SPERRY is an editor and writer for the Shambhala Sun magazine. Sign up to receive news and special offers from Shambhala Publications. Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala. A BEGINNER’S GUIDE TO Meditation Practical Advice and Inspiration from Contemporary Buddhist Teachers Edited by Rod Meade Sperry and the Editors of the Shambhala Sun SHAMBHALA Boston & London 2014 Shambhala Publications, Inc. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com © 2014 by Shambhala Sun Cover art: André Slob Cover design: Liza Matthews All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

The Koan : Texts and Contexts in Zen Buddhism

Introduction Koan Tradition: Self-Narrative an d Contemporary Perspective s STEVEN HEINE AND DALE S. WRIGHT Aims The term koa n (C . kung-an, literall y "public cases" ) refer s t o enigmati c an d often shockin g spiritual expressions based o n dialogica l encounters between masters and disciples that were used as pedagogical tools for religious training in th e Ze n (C . Ch'an) Buddhist tradition . Thi s innovative practic e i s one of the best-known and most distinctive elements of Zen Buddhism. Originating in T'ang/Sung China, the use of koans spread t o Vietnam, Korea, an d Japa n and now attracts international attention. What is unique about the koan is the way i n whic h i t i s thought t o embod y th e enlightenmen t experienc e o f th e Buddha an d Ze n masters through a n unbroken lin e of succession. Th e koan was conceived as both the tool by which enlightenment is brought abou t an d an expression of the enlightened mind itself. Koans ar e generally appreciate d today as pithy, epigrammatic, elusiv e utterances that see m to hav e a psycho- therapeutic effec t i n liberatin g practitioner s fro m bondag e t o ignorance , a s well a s fo r th e wa y they ar e containe d i n th e complex , multilevele d literary form o f koan collectio n commentaries . Perhap s n o dimensio n o f Asian reli - gions has attracted s o much interest and attention i n the West, from psycho - logical interpretations and comparative mystical theology to appropriations i n beat poetry and deconstractive literary criticism. -

Soto Zen: an Introduction to Zazen

SOT¯ O¯ ZEN An Introduction to Zazen SOT¯ O¯ ZEN: An Introduction to Zazen Edited by: S¯ot¯o Zen Buddhism International Center Published by: SOTOSHU SHUMUCHO 2-5-2, Shiba, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-8544, Japan Tel: +81-3-3454-5411 Fax: +81-3-3454-5423 URL: http://global.sotozen-net.or.jp/ First printing: 2002 NinthFifteenth printing: printing: 20122017 © 2002 by SOTOSHU SHUMUCHO. All rights reserved. Printed in Japan Contents Part I. Practice of Zazen....................................................7 1. A Path of Just Sitting: Zazen as the Practice of the Bodhisattva Way 9 2. How to Do Zazen 25 3. Manners in the Zend¯o 36 Part II. An Introduction to S¯ot¯o Zen .............................47 1. History and Teachings of S¯ot¯o Zen 49 2. Texts on Zazen 69 Fukan Zazengi 69 Sh¯ob¯ogenz¯o Bend¯owa 72 Sh¯ob¯ogenz¯o Zuimonki 81 Zazen Y¯ojinki 87 J¯uniji-h¯ogo 93 Appendixes.......................................................................99 Takkesa ge (Robe Verse) 101 Kaiky¯o ge (Sutra-Opening Verse) 101 Shigu seigan mon (Four Vows) 101 Hannya shingy¯o (Heart Sutra) 101 Fuek¯o (Universal Transference of Merit) 102 Part I Practice of Zazen A Path of Just Sitting: Zazen as the 1 Practice of the Bodhisattva Way Shohaku Okumura A Personal Reflection on Zazen Practice in Modern Times Problems we are facing The 20th century was scarred by two World Wars, a Cold War between powerful nations, and countless regional conflicts of great violence. Millions were killed, and millions more displaced from their homes. All the developed nations were involved in these wars and conflicts. -

Zen Masters at Play and on Play: a Take on Koans and Koan Practice

ZEN MASTERS AT PLAY AND ON PLAY: A TAKE ON KOANS AND KOAN PRACTICE A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Brian Peshek August, 2009 Thesis written by Brian Peshek B.Music, University of Cincinnati, 1994 M.A., Kent State University, 2009 Approved by Jeffrey Wattles, Advisor David Odell-Scott, Chair, Department of Philosophy John R.D. Stalvey, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements iv Chapter 1. Introduction and the Question “What is Play?” 1 Chapter 2. The Koan Tradition and Koan Training 14 Chapter 3. Zen Masters At Play in the Koan Tradition 21 Chapter 4. Zen Doctrine 36 Chapter 5. Zen Masters On Play 45 Note on the Layout of Appendixes 79 APPENDIX 1. Seventy-fourth Koan of the Blue Cliff Record: 80 “Jinniu’s Rice Pail” APPENDIX 2. Ninty-third Koan of the Blue Cliff Record: 85 “Daguang Does a Dance” BIBLIOGRAPHY 89 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are times in one’s life when it is appropriate to make one’s gratitude explicit. Sometimes this task is made difficult not by lack of gratitude nor lack of reason for it. Rather, we are occasionally fortunate enough to have more gratitude than words can contain. Such is the case when I consider the contributions of my advisor, Jeffrey Wattles, who went far beyond his obligations in the preparation of this document. From the beginning, his nurturing presence has fueled the process of exploration, allowing me to follow my truth, rather than persuading me to support his.