Researchcommons.Waikato.Ac.Nz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gotische Schrift

l Gutenberg l Gotische Schrift l Schwabacher l Fraktur l Renaissance-Antiqua l Barock-Antiqua l Klassizistische Antiqua l Egyptienne l Grotesk l Jugendstil DIE ENTWICKLUNG DER DRUCKSCHRIFTEN l Johannes Gensfleisch, genannt Gutenberg * um 1400 in Mainz † 1468 ebenda Mit Gutenbergs Erfindung des Buchdrucks mit beweglichen Metalllettern und der Druckerpresse begann eine ganz neue Epoche. Die Verwendung der beweglichen Lettern ab 1450 revolutionierte die her- kömmliche Methode der Buchproduktion (Handschriften). Der Buchdruck breitete sich schnell in Europa und später in der ganzen Welt aus. Es begann die große Zeit der Entwicklung der Druckschriften. Im deutschsprachigen Raum setzten sich die gebrochenen Schrif- ten durch: Textura (Gotisch), Schwabacher, Fraktur und Kanzlei. Im italienischen Sprachraum konnte sich die gotische Schrift nicht durchsetzen. Dort entstand um 1300 die Rotunda oder Rundgotisch, eine offene Schrift von guter Lesbarkeit und Vorläufer der Antiqua-Schriften. GEBROCHENE SCHRIFTEN l Gotische Schrift (1300 – 1450) Von der Normandie breitete sich in Frank- reich ein neuer Stil aus: die Gotik. Dem Baustil entsprechend war auch die Schrift kantig und hochaufragend, das Schriftbild wirkte eng und düster. Damals bestimmte der christliche Glaube maßgebend das Leben und Kunstschaffen. Die Schrift der Zeit, die Textura, wurde ihrer würdevollen Form wegen hauptsäch- lich für liturgische Bücher verwendet. Auch Gutenberg schnitt seine Typen in dieser Schrift für seine Bibel. Daneben entwickelten sich die gotischen Buchkursiven mit ihren teilweise verschleif- ten Formen von großer Lebendigkeit. GEBROCHENE SCHRIFTEN l Schwabacher (1400) Im 15. Jhd. entstand durch die Vermi- schung der Textura mit der gotischen Kursivschrift die gut lesbare Schwabacher mit ihren offenen Formen. Der derbe Charakter brachte ihr gro- ße Beliebtheit und sie wurde bald zur meistgedruckten Schrift der volkstümlichen Literatur. -

Modernizacijos Atspindžiai Lietuvos Taikomojoje Grafikoje. Art Deco Tipografika Ir Jos (Re)Aktualizacija

VILNIAUS DAILĖS AKADEMIJA GRAFINIO DIZAINO KATEDRA Magistro baigiamasis darbas Modernizacijos atspindžiai Lietuvos taikomojoje grafikoje. Art deco tipografika ir jos (re)aktualizacija Atliko: Jolanta Klišonytė . (parašas) Darbo vadovas: Prof. dr. Giedrė Jankevičiūtė . (parašas) Recenzentas: Dr. Gintarė Žemaitytė . (parašas) Vilnius 2015 Turinys Įvadas 1. Vakarų modernizmas ir tarpukario Lietuva 1.1.1 Lietuvos gyvenimo pokyčiai ir miesto kultūros raida 1.1.2 Art deco stilius ir jo apraiškos Lietuvoje 2. Tipografikos priemonių taikymas Lietuvos art deco taikomojoje grafikoje 2.1.1 Plakatai 2.1.2 Reklama 2.1.3 Knygų ir žurnalų viršeliai 2.2 Lietuvos tipografikos modernūs bruožai 3. Atvejo studija: Telesforo Kulakausko tipografika 4. Art deco tipografikos (re)aktualizacija Išvados Santrauka / Summary Priedai: A. M. Cassandre Nord Express 1927 plakato semiotinė analizė Literatūra Iliustracijos su pavadinimais 2 Aš, Jolanta Klišonytė, kandidatė grafinio dizaino magistro laipsniui gauti, pareiškiu, kad šis baigiamasis darbas paremtas mano paties tyrimais ir remiasi tik tokia papildoma informacija, kuri nurodyta nuorodose, paaiškinimuose, šaltinių, literatūros bei iliustracijų sąrašuose. Pareiškiu, kad baigiamajame darbe nėra naudojamasi kitų darbais to nenurodant ir nė viena baigiamojo darbo dalis nepažeidžia jokių asmens ar institucijos autorinių teisių. Taip pat nė viena baigiamojo darbo dalis nebuvo pateikta jokiai kitai aukštojo mokslo institucijai kaip akademinis atsiskaitymas ar siekiant gauti mokslo laipsnį. Vilnius, 2015 03 10 3 Įvadas Šią temą pasirinkau todėl, kad mane sudomino art deco stiliaus laikotarpyje pradėta naudoti tipografika ir jos ypatumai. Iki šiol tipografika, kaip XX a. Lietuvos modernizmo bruožas, nebuvo nagrinėta, ir tai mane paskatino labiau domėtis šia tema. Šis tyrimas yra glaudžiai susietas su praktiniu darbu, kuriame nagrinėju art deco modeliavimą šiuolaikiniame kontekste. -

„Bitstream“ Fonts

Key to the „Bitstream“ Fonts The history of typefaces is the history of forgeries. One of the greatest forgers of the 20th century was Matthew Carter. The Bitstream website (http://www.myfonts.com) describes him as follows: Matthew Carter of United Kingdom. Born: 1937 Son of Harry Carter, Royal Designer for Industry, contemporary British type designer and ultimate craftsman, trained as a punchcutter at Enschedé by Paul Rädisch, responsible for Crosfield's typographic program in the early 1960s, Mergenthaler Linotype's house designer 1965-1981. Carter co-founded Bitstream with Mike Parker in 1981. In 1991 he left Bitstream to form Carter & Cone with Cherie Cone. In 1997 he was awarded the TDC Medal, the award from the Type Directors Club presented to those „who have made significant contributions to the life, art, and craft of typography“. Carter’s „significant contribution to the life, art, and craft of typography“ consisted of forging the Linotype typeface collection. Carter can be characterized as a split personality. On the one hand, he has designed several original typefaces. On the other hand, he has forged hundreds of fonts. The following lists reveal that ca. 90% of the „Bitstream“ fonts are forgeries of the fonts contained in the catalog „LinoTypeCollection 1987“ („Mergenthaler Type Library“), i.e. the „Bitstream“ fonts are „nefarious evil knock-off clones“ (Bruno Steinert) of fonts sold by Linotype in the mid-1980s.1 „L“ in the following lists denotes that the font is contained in the „LinoTypeCollection 1987“. In the mid-1980s, the Linotype library comprised hundreds of typefaces with a total of 1700 fonts. -

Calligraphic Tendencies in the Development of Sanserif Types in the Twentieth Century

Keith Tam 62 Calligraphic tendencies in the development of sanserif types in the twentieth century Abstract Dissertation submitted in Sanserif typefaces are often perceived as something inextricably linked partial fulfillment of the to ideals of Swiss modernism. They are also often thought of as some- requirements for the thing as far as one can get from calligraphic writing. Yet, throughout Master of Arts in Typeface Design, University of the twentieth century and especially in the past decade or so, the design Reading, 2002 of sanserif typefaces have been consistently inspired by calligraphic writing. This dissertation hence explores the relationship between calli- graphic writing and the formal developments of sanserif typefaces in the twentieth century. Although type design is an inherently different dis- cipline from writing, conventions of calligraphic writing did and still do impose certain important characteristics on the design of typefaces that modern readers expect. This paper traces and analyzes the formal devel- opments of sanserif typefaces through the use of written forms. It gives a historical account of the development of sanserif typefaces by charting six distinct phases of sanserif designs that were in some ways informed by calligraphic writing: • Humanist sanserifs: Britain 1900s • Geometric sanserifs: 1920s–30s • Contrast sanserifs: 1920s–50s • Sanserif as a book type: 1960s–80s • Neo-humanist sanserifs: 1990s Three primary ways to create calligraphic writing, namely the broadnib pen, flexible pointed pen and monoline pen are studied and linages drawn to how designers imitate or subvert the conventions of these tools. These studies are put into historical perspective and links made to the contexts of use. -

Bitstream Font Name Aliases Fontotéka 3.0 Compiled by Petr Somol, Based on Jon A

Bitstream Font Name Aliases fontotéka 3.0 Compiled by Petr Somol, based on Jon A. Pastor‘s list from http://cgm.cs.mcgill.ca/~luc/jonpastor.txt. E-mail: [email protected] The list should not be considered complete, nor accurate. It is more a work in progress than anything else. Bitstream Name Common Name Designer(s) Date(s) Orig. Remarks/Attributions Vend. (all) (M.Macrone/J.Pastor,P.S.) (M.M,P.S.) (J.P., P.S.) Aachen Aachen Colin Brignall, Alan Meeks 1969-1977 17 Ad Lib Ad Lib Freeman Craw 1961 6 Aldine 401 Bembo Stanley Morison after Francesco 1929 after 1,4 Griffo / Giovanni Tagliente 1495 / 1520 Aldine 721 Plantin Frank Hinman Pierpont after ~1930 after 1,4 Robert Granjon‘s type used by 16th ~1550 / 16h century printer Christophe Plantin cent. Alternate Gothic No. 2 Alternate Gothic Morris Fuller Benton 1903 6 Amazone Amazone Leonard H. D. Smit 1958 12 Amelia Amelia Stanley Davis 1967 18, 2 American Text American Text Morris Fuller Benton 1932 6 Americana Americana Richard Isbell, Whedon Davis 1965 6 Aurora Aurora ? 1928 (c.) 11 Baker Signet Baker Signet Arthur Baker 1965 18 Balloon Balloon Max R. Kaufmann 1939 6 Bank Gothic Bank Gothic Morris Fuller Benton 1930-33 6 Baskerville Baskerville George W. Jones after John 1929 after 2 Baskerville ~1754-1775 Baskerville No.2 Baskerville No.2 ? ? 19 Bauer Bodoni Bauer Bodoni Heinrich Jost, Louis Höll after 1926 after 8 Giambattista Bodoni ~1800 Bell Gothic Bell Gothic Chauncey H. Griffith 1938 2 Belwe Belwe Georg Belwe before 1950 20 Bernhard Bold Con- Bernhard Bold Con- Lucian Bernhard -

Neotipografia Material Poetics In

NEO-TIPO-GRAFÍA: MATERIAL POETICS IN THE SPANISH HISTORICAL AVANT-GARDE Zachary Rockwell Ludington Severna Park, Maryland Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2007 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Spanish, Italian & Portuguese University of Virginia August, 2014 © 2014 Zachary Rockwell Ludington 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND DEDICATION I must first extend my warmest thanks to my advisor, Andrew A. Anderson, for his scholarship and for his sharp and supportive critical eye. My work in this dissertation owes a great deal not only to his previous research but also to his helpful comments and his guidance throughout the course of the project. I would also like to thank every member of the Department of Spanish, Italian & Portuguese at the University of Virginia, past and present. I owe specific debts of gratitude to a few friends in the department who have especially enriched my experience during my time at the University, both academically and personally. They are Fernando Operé, David T. Gies, Gustavo Pellón, Randolph Pope, Mané Lagos, Daniel Chávez, Eli Carter, Omar Velázquez Mendoza, Tally Sanford, Shawn Harris, Julia Garner, Luca Prazeres, Diana Arbaiza, Stephen Silverstein, Jülide Etem, Sarah Bogard, Alejandra Gutiérrez, Keith Howard, Tim McAllister, Adriana Rojas Campbell, Gabrielle Miller, Gillian Price, Melissa Frost, and Diana Galarreta. Friends and colleagues outside the department but ever present and interested in my work are Ana Elia García Pérez, Nathan Brown, John Lyons, Paul A. Cantor, Shaun Cullen, Chicho Lorenzo, Tico Braun, Antonio Reyes, Manuela Jiménez, Brian Carr, and Erik J. -

New Typography in Scandinavia 2 in the Design Histories of Kjetil Fallan and Julia Meer.2 Titled

New Ty pog raphy in Scandinavia: Domesticating theory and practice amongst the graphic trades, 1927–43 Trond Klevgaard A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Royal College of Art for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The Royal College of Art / Victoria and Albert Museum 22 December 2017 79,976 words ii Copyright statement This text represents the submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Royal College of Art. This copy has been supplied for the purpose of research for private study, on the understanding that it is copyright material, and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. iii Abstract This work provides the first extended account of New Typography’s path in Scandinavian countries, a topic which has yet to receive attention beyond a handful of articles and book chapters. Based on an exhaustive study of graphic trade journals published in Denmark, Norway and Sweden between the years of 1927 and 1943, it charts debate on New Typography and discusses the journals’ changing designs. Additional visual material has been sourced from a number of Scandinavian archives. In discussing the spread of New Typography’s theory and aesthetic from elsewhere in Europe, and then primarily from Germany, the thesis uses the concepts of domestication and networks, rather than those of diffusion or influence and centre–periphery. Dealing with a period in which the graphic designer had yet to appear as a professional figure, New Typography’s impact on a range of professional groups — all of which held responsibility for the design of graphic materials — is considered. -

Alphabet Book, So If You’D Like Curved Leg to Find a Letter, You’Re Going to Have to Know What Letter It Comes After

history and meggsy The evolution of the i and j Kerning typo graphy/graphers Lowercase/uppercase (majuscule/miniscule) Mechanical typesetting The Beowulf typeface Old style figures Distinguishing typefaces Roman Futura Serif/Sans Serif Claude Garamond and his face The W and U, and their parent the V Bradbury Thompson (badass) Univers (Adrian Frutiger) Wolfgang Weingart, educator Hermann Zapf, calligrapher drooling and geeky Chinese Calligraphy Emigre Q x height rhetoric and banter Handwriting Never! Prehistoric vs PostScript Y - the Crystal Goblet R Of course this is an alphabet book, so if you’d like curved leg to find a letter, you’re going to have to know what letter it comes after. If you’re not to good with the alphabet, you can find it on the V page. Fonts that are used by a printer are actually computer programs. They consist of 3 10 lineto a lot of numbers and statements 3 7 lineto like the commands lineto or curve- to which draw (think hard) lines and 487 256 522 7 9 c 205 urv curves. The example b is shown eto For the Beowulf 4 9 3 5 2 with the postscript code that is used 2 5 typeface, van 6 5 4 0 to draw it. 1 1 Rossum and van 0 6 c u r v e Blockum replaced all 0 10 lineto t o the lineto and curveto commands with something they 5 6 5 1 2 wrote called freakto. Instead of a straight line or a curve, 4 5 0 0 - 1 2 it draws a random spikey-looking line. -

Sans Serif Typefaces By: Years, All of Which Were Designed by Ben- Ton and Issued by A.T.F

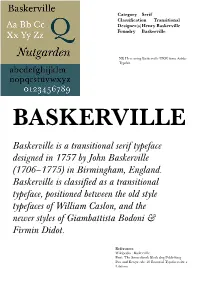

Category Serif Classification Transitional Designer(s) Henry Baskerville Foundry Baskerville NB Here using Baskerville URW from Adobe Typekit BASKERVILLE Baskerville is a transitional serif typeface designed in 1757 by John Baskerville (1706–1775) in Birmingham, England. Baskerville is classified as a transitional typeface, positioned between the old style typefaces of William Caslon, and the newer styles of Giambattista Bodoni & Firmin Didot. References Wikipedia : Baskerville Font: The Sourcebook Black dog Publishing Pau and Berger eds: 30 Essential Typefaces for a Lifetime History CHARACTERISTICS In Birmingham, England, Henry Baskerville ad- vanced the use of more delicate typefaces that could The Baskerville typeface is the result of withstand the repeated poundings on the press. He John Baskerville’s intent to improve upon also developed smoother paper so the typefaces could the types of William Caslon. He was aim- print without breaks or clogs. Had an airy quality ing at simplicity and quiet refinement due to the lightness of the letterforms and generosity though: of the page margins. Melted down his type after each printing. • increasing the contrast between thick and thin strokes Baskerville’s typeface was the culmination of a larg- • making the serifs sharper and more er series of experiments to improve legibility which tapered also included paper making and ink manufactur- • shifting the axis of rounded letters to a ing. His background as a writing master is evident more vertical position. in the distinctive swash tail on the uppercase Q and • making curved strokes more circular in in the cursive serifs in the Baskerville Italic. shape and making characters more regu- lar. -

Capítulo 1. Historia De La Tipografía

Historia de la tipografía En este capítulo conoceremos el desarrollo de la tipogra- fía, desde Gutenberg, con la invención de los tipos móvi- les de metal, hasta la actualidad. Encontraremos informa- ción de tipógrafos, tipografías, innovaciones técnicas, fundiciones tipográficas y otros acontecimientos relevan- tes que ocurrieron durante estos 5 siglos y que además 1nos adentrarán en el universo de la tipografía. 1.1 Incunables: 1440-1500 Con la disponibilidad del papel, la impresión con bloques de madera tallada y la creciente demanda de libros, naciones como Italia, Alemania, Francia y los Países Bajos, buscaban la produc- ción de textos por medio de la mecanización utilizando tipos móviles. Alrededor de 1440, Johann Gensfleisch zum Gutenberg, desarrolló en Alemania una técnica para elaborar moldes de tipos que se utilizarían para la impresión de letras individuales (los chi- nos fueron los primeros en utilizar tipos móviles, hechos de made- ra, durante la primera mitad del siglo xi); escogió el tipo textura como modelo, imitando el trabajo de los escribas de la época, para que el nuevo estilo fuera aceptado. La obra más representa- tiva de Gutenberg es su Biblia de 42 líneas que desarrolló con esta técnica, la cual estuvo vigente por 500 años. Los tipos móviles 1 Retrato del s. xvi de la posible apariencia de Gutenberg (A. Thevet, Pourtraits et vies, 1584). Página de la Biblia de 42 líneas de Gutenberg. Las ilustraciones, así como algunos detalles en la composición del texto, fueron añadidas a mano después de haberse impreso. Este ejemplar se encuentra en la Biblioteca Británica en 2 Londres. -

2012 Slanted 380356

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Form folgt Architektur: deutsche Egyptienne-Schriften des frühen 20. Jahrhunderts und ihre Schriftproben Lommen, M. Publication date 2012 Document Version Final published version Published in Slanted Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Lommen, M. (2012). Form folgt Architektur: deutsche Egyptienne-Schriften des frühen 20. Jahrhunderts und ihre Schriftproben. Slanted, 20, 108-111. http://www.slanted.de/shop/slanted-20-slab-serif General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:04 Oct 2021 WINTIR -ISSN 2012113 1887-8510 EUR DE EUR CH CHf UK US OTHERS ... , I" .... I "'"111 ,.11111 141 251 118 I S 28 I 18 .... •' .-� •·. ;..:-= ' L l.' � . I.,. 11 . � · , .. · ..,., l -- . -.. I 'lv � · � • ..· - .,..._'!- .,, ,"t" ,.- ( ' ... • I J -!lil ) �:· I ·�.. -

Doug Olena Geboren Am 5

Doug Olena Geboren am 5. Mai 1953. http://www.olena.com/ Abernathy Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ Abernathy Italic Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ Adastra Doug Olena Linotype ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 1234567890 Adastra Plain Doug Olena Linotype Herbert Thannhaeuser · 1928 · D. Stempel AG Alais Califfa Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ Alfereta Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ Ambergris Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ Ambergris Italic Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ Ampersands Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ ABCDEFGHIJKLM abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz Aquarium Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ Ark Casual Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ Arwen Doug Olena Linotype ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 1234567890 Barko Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ Barko Italic Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ http://www.klingspor-museum.de Basaltic Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ Basaltic Incline Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ Basaltic Foil Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ Basaltic Foil Incline Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ Blackface Two Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ Blocks Doug Olena Linotype ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 1234567890 Bones Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ FFD Broadway Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ FFD Broadway Engraved Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ Morris F. Benton · 1928 · ATF Burrito Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ Calvin Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ Carver’s Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ Casablanca Doug Olena http://www.olena.com/ Chevalier