Typography Is a Very Powerful Design Element

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smashing Ebook

IMPRINT Imprint © 2014 Smashing Magazine GmbH, Freiburg, Germany ISBN (PDF): 978-3-94454087-0 Cover Design: Veerle Pieters eBook Strategy and Editing: Vitaly Friedman Technical Editing: Cosima Mielke Planning and Quality Control: Vitaly Friedman, Iris Lješnjanin Tools: Elja Friedman Syntax Highlighting: Prism by Lea Verou Idea & Concept: Smashing Magazine GmbH 2 About This Book Slow loading times break the user experience of any web- site—no matter how well crafted it might be. In fact, it only takes three seconds until users lose their interest in a site if they don’t get a response immediately. If another site happens to be 250ms faster than yours, then users are more inclined to switch to a competitor’s website in no time. Web fonts, heavy JavaScript, third-party widgets — all of them can sum up to become a real performance bot- tleneck. Nevertheless, tracking that down does not only improve loading times but also results in a much snappi- er experience and a higher user engagement. In this eBook, we’ve compiled an entire selection of front-end and server-side techniques that will help you tackle such bottlenecks. Find out how to speed up exist- ing websites, build high-performance sites (for both mo- bile and desktop), and prepare them for heavy-load situa- tions. Furthermore, you’ll learn more about how perfor- mance improvements and a 97–99 Google PageSpeed score were achieved on Smashing Magazine, as well as how optimization strategies can enhance real-life projects by taking a closer look at Pinterest’s paint performance case study. -

Dockerdocker

X86 Exagear Emulation • Android Gaming • Meta Package Installation Year Two Issue #14 Feb 2015 ODROIDMagazine DockerDocker OS Spotlight: Deploying ready-to-use Ubuntu Studio containers for running complex system environments • Interfacing ODROID-C1 with 16 Channel Relay Play with the Weather Board • ODROID-C1 Minimal Install • Device Configuration for Android Development • Remote Desktop using Guacamole What we stand for. We strive to symbolize the edge of technology, future, youth, humanity, and engineering. Our philosophy is based on Developers. And our efforts to keep close relationships with developers around the world. For that, you can always count on having the quality and sophistication that is the hallmark of our products. Simple, modern and distinctive. So you can have the best to accomplish everything you can dream of. We are now shipping the ODROID U3 devices to EU countries! Come and visit our online store to shop! Address: Max-Pollin-Straße 1 85104 Pförring Germany Telephone & Fax phone : +49 (0) 8403 / 920-920 email : [email protected] Our ODROID products can be found at http://bit.ly/1tXPXwe EDITORIAL ow that ODROID Magazine is in its second year, we’ve ex- panded into several social networks in order to make it Neasier for you to ask questions, suggest topics, send article submissions, and be notified whenever the latest issue has been posted. Check out our Google+ page at http://bit.ly/1D7ds9u, our Reddit forum at http://bit. ly/1DyClsP, and our Hardkernel subforum at http://bit.ly/1E66Tm6. If you’ve been following the recent Docker trends, you’ll be excited to find out about some of the pre-built Docker images available for the ODROID, detailed in the second part of our Docker series that began last month. -

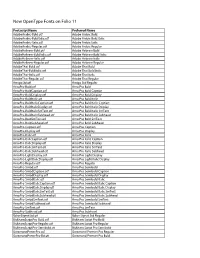

New Opentype Fonts on Folio 11

New OpenType Fonts on Folio 11 Postscript Name Preferred Name AdobeArabic-Bold.otf Adobe Arabic Bold AdobeArabic-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Arabic Bold Italic AdobeArabic-Italic.otf Adobe Arabic Italic AdobeArabic-Regular.otf Adobe Arabic Regular AdobeHebrew-Bold.otf Adobe Hebrew Bold AdobeHebrew-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Hebrew Bold Italic AdobeHebrew-Italic.otf Adobe Hebrew Italic AdobeHebrew-Regular.otf Adobe Hebrew Regular AdobeThai-Bold.otf Adobe Thai Bold AdobeThai-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Thai Bold Italic AdobeThai-Italic.otf Adobe Thai Italic AdobeThai-Regular.otf Adobe Thai Regular AmigoStd.otf Amigo Std Regular ArnoPro-Bold.otf Arno Pro Bold ArnoPro-BoldCaption.otf Arno Pro Bold Caption ArnoPro-BoldDisplay.otf Arno Pro Bold Display ArnoPro-BoldItalic.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic ArnoPro-BoldItalicCaption.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Caption ArnoPro-BoldItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Display ArnoPro-BoldItalicSmText.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic SmText ArnoPro-BoldItalicSubhead.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Subhead ArnoPro-BoldSmText.otf Arno Pro Bold SmText ArnoPro-BoldSubhead.otf Arno Pro Bold Subhead ArnoPro-Caption.otf Arno Pro Caption ArnoPro-Display.otf Arno Pro Display ArnoPro-Italic.otf Arno Pro Italic ArnoPro-ItalicCaption.otf Arno Pro Italic Caption ArnoPro-ItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Italic Display ArnoPro-ItalicSmText.otf Arno Pro Italic SmText ArnoPro-ItalicSubhead.otf Arno Pro Italic Subhead ArnoPro-LightDisplay.otf Arno Pro Light Display ArnoPro-LightItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Light Italic Display ArnoPro-Regular.otf Arno Pro Regular ArnoPro-Smbd.otf -

AVENIR Family

An Introduction To The AVENIR Family By Stacey Chen O V E R V I E W l Avenir was designed by Adrian Frutiger. l The typeface was first released in 1988 with three weights, before being expanded to six weights. l In 2004, together with Akira Kobayashi, Frutiger reworked the Avenir family. l Avenir has now become a common font in web, print, and graphic design, etc. l Frutiger was born in Unterseen, Switzerland 1928. l At age 16, Frutiger was apprenticed as a compositor to a printer, while taking classes in woodcuts and drawing. l With his second wife, Frutiger had two daughters, who both experienced mental health problems and committed suicide as adolescents. l Frutiger spent most of his professional career working in Paris and living in France, returning to Switzerland later in life. A D R I A N F R U T I G E R l Charles Peignot of Deberny Et Peignot recruited Frutiger based on the quality of the wood- engraved illustrations of his essay. l Impressed by the success of Futura typeface, Peignot encouraged a new, geometric sans-serif type in competition. l Frutiger disliked the regimentation of Futura, and persuaded Peignot that the new sans-serif be based on the realist model. l In 1988, Frutiger completed the family Avenir. Frutiger intended the font to be a more human version of geometric sans-serif types popular in the 1930s, such as Erbar and Futura. A D R I A N F R U T I G E R “Avenir” = “Future” French English A V E N I R i s l Futura is a geometric sans-serif typeface designed in 1927 by Paul Renner. -

Vision Performance Institute

Vision Performance Institute Technical Report Individual character legibility James E. Sheedy, OD, PhD Yu-Chi Tai, PhD John Hayes, PhD The purpose of this study was to investigate the factors that influence the legibility of individual characters. Previous work in our lab [2], including the first study in this sequence, has studied the relative legibility of fonts with different anti- aliasing techniques or other presentation medias, such as paper. These studies have tested the relative legibility of a set of characters configured with the tested conditions. However the relative legibility of individual characters within the character set has not been studied. While many factors seem to affect the legibility of a character (e.g., character typeface, character size, image contrast, character rendering, the type of presentation media, the amount of text presented, viewing distance, etc.), it is not clear what makes a character more legible when presenting in one way than in another. In addition, the importance of those different factors to the legibility of one character may not be held when the same set of factors was presented in another character. Some characters may be more legible in one typeface and others more legible in another typeface. What are the character features that affect legibility? For example, some characters have wider openings (e.g., the opening of “c” in Calibri is wider than the character “c” in Helvetica); some letter g’s have double bowls while some have single (e.g., “g” in Batang vs. “g” in Verdana); some have longer ascenders or descenders (e.g., “b” in Constantia vs. -

Fonts for 2021!

Fonts for 2021! Amienne* Basic Class Display Fonts 1234567890 1234567890 * Font families available abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ Anaconda Baveuse Abigail * 1234567890 1234567890 1234567890 abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz avbcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ Argentine Belinda* Abyss* 1234567890 1234567890 1234567890 abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ Arizona Benjamin* Adria Deco 1234567890 1234567890 1234567890 abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ Austere Berkley* Agnes 1234567890 1234567890 1234567890 abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ Ballad Script Bernhard Fashion FS Aladdin* 1234567890 1234567890 1234567890 abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ Bamboo Big Fiction* Alex Brush 1234567890 1234567890 1234567890 abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ Banker -

The Press of A. Colish Archives

Special Collections Department The Press of A. Colish Archives 1913 - 1990 (bulk dates 1930s - 1950s) Manuscript Collection Number: 358 Accessioned: Purchase, September 1991. Extent: 5 linear ft. plus oversize material Content: Correspondence, galley and page proofs, drafts, notes, photographs, negatives, illustrations, advertisements, clippings, broadsides, books, chapbooks, pamphlets, journals, typography specimens, financial documents, and ephemera. Access: The collection is open for research. Processed: March 1998, by Shanon Lawson for reference assistance email Special Collections or contact: Special Collections, University of Delaware Library Newark, Delaware 19717-5267 (302) 831-2229 Table of Contents Biographical and Historical Note Scope and Contents Note Series Outline Contents List Biographical and Historical Note American fine printer and publisher Abraham Colish (1882-1963) immigrated with his family to the United States from Eastern Europe in the late nineteenth century. In 1894, at the age of twelve, he took an after-school job with a small printing shop in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Over the next few years, his duties progressed from sweeping the shop and selling papers to feeding the press and composing type. When he was sixteen, Colish and his mother moved to New York City, where he quickly found a position as a typesetter for Kane Brothers, a Broadway printing company. In 1907, Colish left his position as a composing room foreman at Rogers and Company and opened his own composing office. His business specialized in advertising typography and is credited as the first shop to exclusively cater to the advertising market. By the next year, Colish moved into larger quarters and began printing small orders. After several moves to successively larger offices in New York City, the Press of A. -

Eurostile Masking Film and Many Other Graphic the Strong Solid Look of Eurostile Is EXTRA BOLD Croissant Ron* Aids Illustrated

( £.%!?() H AaBbCcDdFeFfGgHhIiJjKkLIMmNnOoPp Qq Rr SsTt UuVvWwXxYyZz1234567890&7ECESS PUBLISHED BY INTERNATIONALTYPEFACE CORPORATION,VOLUME SEVEN, NUMBER ONE,MARCH 1980 UPPER AND LOWER CASE.THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF TYPOGRAPHICS VOLUME SEVEN. NUMBER ONE, MARCH, 1980 HERB LUBALIN. EDITORIAL & DESIGN DIRECTOR AARON BURNS, EDITORIAL DIRECTOR EDWARD RONOTHALER. EDITORIAL DIRECTOR MARION MULLER, ASSOCIATE EDITOR MICHAEL ARON. JASON CALFO, HAU-CHEE CHUNG. CLAUDIA CLAY, TONY DISPIGNA, SHARON GRESH. LESLIE MORRIS. KAREN ZIAMAN. JUREK WAJDOWIC2. ART 6 PRODUCTION EDITORS JOHN PRENTKI, BUSINESS MANAGER, LORNA SHANKS, ADVERTISING MANAGER EDWARD GOTTSCHALL. EDITORIAL COORDINATOR. HELENA WALLSCHLAG. TRAFFIC AND PRODUCTION MANAGER INTERNATIONAL TYPEFACE CORPORATION 1979 PUBLISHED FOUR TIMES A YEAR IN MARCH. JUNE. SEPTEMBER AND DECEMBER BY INTERNATIONAL TYPEFACE CORPORATION 216 EAST 4STH STREET. NEW YORK. N.,10017 A JOINTLY OWNED SUBSIDIARY OF PHOTO.LETTERING, INC. AND LUBALIN. BURNS ar CO., INC. CONTROLLED CIRCULATION POSTAGE PAID AT NEW YORK. N.Y. AND AT FARMINGDALE. N.Y. USTS PURL 073430 PUBLISHED IN U.S.A. ITC OFFICERS, EDWARD RONOTHALER, CHAIRMAN AARON BURNS. PRESIDENT HERB LUBALIN. EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT JOHN PRENTKI,VICE PRESIDENT. GENERAL MANAGER BOB FARBER. SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT ED BENGUIAT.VICE PRESIDENT STEPHEN KOPEC.VICE PRESIDENT U.S. SINGLE COPIES 51.50 ELSEWHERE. SINGLE COPIES 52.50 TO QUALIFY FOR FREE SUBSCRIPTION COMPLETE AND RETURN THE SUBSCRIPTION FORM IN THIS ISSUE TO ITC OR WRITE TO THE ITC EXECUTIVE OFFICE. 2 HANIMARSKJOLD PLAZA. NEW YORK, N.Y. 10017 In This Issue: Editorial Are You Confused? ITC is producing a 100,000 word diagrammatic and pictorial report on the new typographic technologies. Do the new technologies get you up, or down? Do you know which ones matter It's called Vision'80s, and Ed Gottschall tells you to you—and how? Do you feel challenged or threatened by them? about it. -

Type Classification Ebook

Before You Begin... 6.The last 4 pages of the book explain what a “font flag” is and gives an example and also what a “font specimen sheet” it and an example. This book has been made to help you learn the 10 broad classifications of type. I won’t go into why you need to know them, but just face the fact... Regards, k you do. This book was specifically made for printing and web viewing. Jacob Cass jacobcassATjustcreativedesignDOTcom o Below is a brief description of what is inside the book and how it is layed http://justcreativedesign.com o out which will help you get more out of the book. © Copyright Jacob Cass - This book is licensed under a Attribution b Noncommercial Share Alike 2.0 Generic Creative Commons license. This 1. On the next page there are all 10 type classifications on one page. (ie. d Humanist, Garalde, Didone, Transitional, Lineal, Mechanistic, Blackletter, means you CAN copy, distribute, display, and use this work for any Decorative, Script and Manual.) These are the types classifications we will purpose under the conditions that you give me credit for the work and n that you do not make money from it, nor build upon or alter the work. be discussing. a 2. On the next two pages are layout guides to help you get familar with the layout of the book. H 3. The next page then continues to give a description of each type classification (ie. the 10 mentioned above). It will also provide the history n and characteristics of each type classification and appropriate font o examples on the same page as seen in the LAYOUT GUIDE. -

Bibliographica (Issue 3)

Bibliographica (Issue 3) Item Type Newsletter (Paginated) Authors Henry, John G.; Schanilec, Gaylord; Hardesty, Skye Citation Bibliographica (Issue 3) 2005-07, Download date 26/09/2021 12:16:22 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/106505 Issue Number 3 Summer 2005 biBIblBiLIoOGgRrAPapHhICAic a Cedar Creek Press collection of text sizes in Caslon, Garamond, Euse- bius, and Goudy Oldstyle. By John G. Henry Henry’s journey has taken him through high school, Cedar Creek Press has produced a variety of printed a B.A. from the University of Iowa with majors in materials since its inception in 1967. What started English & Journalism, an M.S. degree in Printing entirely as a hobby venture by a high school student Technology from the Rochester Institute of Tech- and a single press has expanded to fill a 25’ x 50’ nology, and many other practical learning experiences. workshop. The reason for being of Cedar Creek Cedar Creek Press has published many books of Press has always been the printer’s enjoyment of Poetry by primarily Midwestern poets. Mostly first the letterpress process. books for the authors, the editions have been small, Proprietor John G. Henry spent many hours poring but have given a published voice to many fine poets. over the catalogs of the Kelsey Company, making The emphasis of the publishing has been to produce his wish-list and saving his allowance for purchase nicely-designed and produced books at a reasonable of a basic set of printing equipment. One day Henry price. saw an advertisement in the local classifieds for an Recent ventures have been in the world of miniature entire print shop for $50. -

ERIC GILL SAGGIO an Essay SULLA on TIPO Typography GRAFIA

ERIC GILL SAGGIO An Essay SULLA on TIPO Typography GRAFIA RONZANI EDITORE typographica storia e culture del libro 2 Eric Gill, foto di Howard Coster, 1928 ERIC GILL Saggio sulla tipografia Ronzani Editore Eric gill, Saggio Sulla tipografia Titolo originale: An Essay on Typography Traduzione di Lucio Passerini Seconda edizione italiana interamente riveduta dall’editore con il testo originale inglese © 2019 Ronzani Editore S.r.l. | Tutti i diritti riservati www.ronzanieditore.it | [email protected] ISBN 978-88-94911-15-2 SOMMARIO Introduzione, di Lucio Passerini 7 Saggio sulla tipografia 23 Il Tema 25 1. Composizione del tempo e del luogo 29 2. Disegno delle lettere 45 3. Tipografia 77 4. Incisione dei punzoni 89 5. Carta e inchiostro 93 6. Il letto di Procuste 99 7. Lo strumento 105 8. Il libro 111 9. Perché le lettere ? 123 An Essay on Typography 135 INTRODUZIONE di Lucio Passerini La prima edizione di questo saggio di Eric Gill fu eseguita sotto il diretto controllo dell’autore. Composta nel 1931, venne stampata in 500 copie firmate, su carta apposita- mente fabbricata a mano, nella tipografia che lo stesso Gill aveva impiantato l’anno precedente insieme al gene- ro René Hague presso la casa in cui risiedeva. Il libro fu composto con un nuovo carattere disegnato apposita- mente da Gill per questa impresa editoriale di famiglia, inciso e fuso per la composizione a mano dalla Caslon Letter Foundry di Londra. Il carattere venne chiamato Joanna, come la figlia di Gill, moglie di René Hague. Pubblicato a Londra da Sheed & Ward, il volume portava sulla sovraccoperta la dicitura « Printing & Piety. -

The Impact of the Historical Development of Typography on Modern Classification of Typefaces

M. Tomiša et al. Utjecaj povijesnog razvoja tipografije na suvremenu klasifikaciju pisama ISSN 1330-3651 (Print), ISSN 1848-6339 (Online) UDC/UDK 655.26:003.2 THE IMPACT OF THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF TYPOGRAPHY ON MODERN CLASSIFICATION OF TYPEFACES Mario Tomiša, Damir Vusić, Marin Milković Original scientific paper One of the definitions of typography is that it is the art of arranging typefaces for a specific project and their arrangement in order to achieve a more effective communication. In order to choose the appropriate typeface, the user should be well-acquainted with visual or geometric features of typography, typographic rules and the historical development of typography. Additionally, every user is further assisted by a good quality and simple typeface classification. There are many different classifications of typefaces based on historical or visual criteria, as well as their combination. During the last thirty years, computers and digital technology have enabled brand new creative freedoms. As a result, there are thousands of fonts and dozens of applications for digitally creating typefaces. This paper suggests an innovative, simpler classification, which should correspond to the contemporary development of typography, the production of a vast number of new typefaces and the needs of today's users. Keywords: character, font, graphic design, historical development of typography, typeface, typeface classification, typography Utjecaj povijesnog razvoja tipografije na suvremenu klasifikaciju pisama Izvorni znanstveni članak Jedna je od definicija tipografije da je ona umjetnost odabira odgovarajućeg pisma za određeni projekt i njegova organizacija s ciljem ostvarenja što učinkovitije komunikacije. Da bi korisnik mogao odabrati pravo pismo za svoje potrebe treba prije svega dobro poznavati optičke ili geometrijske značajke tipografije, tipografska pravila i povijesni razvoj tipografije.