Vision Performance Institute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Garamond and the French Renaissance Garamond and the French Renaissance Compiled from Various Writings Edited by Kylie Harrigan for Everyone Ever

Garamond and The French Renaissance Garamond and The French Renaissance Compiled from Various Writings Edited by Kylie Harrigan For Everyone ever Design © 2014 Kylie Harrigan Garamond Typeface The French Renassaince Garamond, An Overview Garamond is a typeface that is widely used today. The namesake of that typeface was equally as popular as the typeface is now when he was around. Starting out as an apprentice punch cutter Claude Garamond 2 quickly made a name for himself in the typography industry. Even though the typeface named for Claude Garamond is not actually based on a design of his own it shows how much of an influence he was. He has his typefaces, typefaces named after him and typeface based on his original typefaces. As a major influence during the 16th century and continued influence all the way to today Claude Garamond has had a major influence in typography and design. Claude Garamond was born in Paris, France around 1480 or 1490. Rather quickly Garamond entered the industry of typography. He started out as an apprentice punch cutter and printer. Working for Antoine Augereau he specialized in type design as well as punching cutting and printing. Grec Du Roi Type The Renaissance in France It was under Francis 1, king of France The Francis 1 gallery in the Italy, including Benvenuto Cellini; he also from 1515 to 1547, that Renaissance art Chateau de Fontainebleau imported works of art from Italy. All this While artists and their patrons in France and and architecture first blossomed in France. rapidly galvanised a large part of the French the rest of Europe were still discovering and Shortly after coming to the throne, Francis, a Francis 1 not only encouraged the nobility into taking up the Italian style for developing the Gothic style, in Italy a new cultured and intelligent monarch, invited the Renaissance style of art in France, he their own building projects and artistic type of art, inspired by the Classical heritage, elderly Leonardo da Vinci to come and work also set about building fine Renaissance commissions. -

Supreme Court of the State of New York Appellate Division: Second Judicial Department

Supreme Court of the State of New York Appellate Division: Second Judicial Department A GLOSSARY OF TERMS FOR FORMATTING COMPUTER-GENERATED BRIEFS, WITH EXAMPLES The rules concerning the formatting of briefs are contained in CPLR 5529 and in § 1250.8 of the Practice Rules of the Appellate Division. Those rules cover technical matters and therefore use certain technical terms which may be unfamiliar to attorneys and litigants. The following glossary is offered as an aid to the understanding of the rules. Typeface: A typeface is a complete set of characters of a particular and consistent design for the composition of text, and is also called a font. Typefaces often come in sets which usually include a bold and an italic version in addition to the basic design. Proportionally Spaced Typeface: Proportionally spaced type is designed so that the amount of horizontal space each letter occupies on a line of text is proportional to the design of each letter, the letter i, for example, being narrower than the letter w. More text of the same type size fits on a horizontal line of proportionally spaced type than a horizontal line of the same length of monospaced type. This sentence is set in Times New Roman, which is a proportionally spaced typeface. Monospaced Typeface: In a monospaced typeface, each letter occupies the same amount of space on a horizontal line of text. This sentence is set in Courier, which is a monospaced typeface. Point Size: A point is a unit of measurement used by printers equal to approximately 1/72 of an inch. -

Design One Project Three Introduced October 21. Due November 11

Design One Project Three Introduced October 21. Due November 11. Typeface Broadside/Poster Broadsides have been an aspect of typography and printing since the earliest types. Printers and Typographers would print a catalogue of their available fonts on one large sheet of paper. The introduction of a new typeface would also warrant the issue of a broadside. Printers and Typographers continue to publish broadsides, posters and periodicals to advertise available faces. The Adobe website that you use for research is a good example of this purpose. Advertising often interprets the type creatively and uses the typeface in various contexts to demonstrate its usefulness. Type designs reflect their time period and the interests and experiences of the type designer. Type may be planned to have a specific “look” and “feel” by the designer or subjective meaning may be attributed to the typeface because of the manner in which it reflects its time, the way it is used, or the evolving fashion of design. For this third project, you will create two posters about a specific typeface. One poster will deal with the typeface alone, cataloguing the face and providing information about the type designer. The second poster will present a visual analogy of the typeface, that combines both type and image, to broaden the viewer’s knowledge of the type. Process 1. Research the history and visual characteristics of a chosen typeface. Choose a typeface from the list provided. -Write a minimum150 word description of the typeface that focuses on two themes: A. The historical background of the typeface and a very brief biography of the typeface designer. -

Cloud Fonts in Microsoft Office

APRIL 2019 Guide to Cloud Fonts in Microsoft® Office 365® Cloud fonts are available to Office 365 subscribers on all platforms and devices. Documents that use cloud fonts will render correctly in Office 2019. Embed cloud fonts for use with older versions of Office. Reference article from Microsoft: Cloud fonts in Office DESIGN TO PRESENT Terberg Design, LLC Index MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS A B C D E Legend: Good choice for theme body fonts F G H I J Okay choice for theme body fonts Includes serif typefaces, K L M N O non-lining figures, and those missing italic and/or bold styles P R S T U Present with most older versions of Office, embedding not required V W Symbol fonts Language-specific fonts MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS Abadi NEW ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Abadi Extra Light ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Note: No italic or bold styles provided. Agency FB MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Agency FB Bold ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Note: No italic style provided Algerian MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 01234567890 Note: Uppercase only. No other styles provided. Arial MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Italic ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Bold ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Bold Italic ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ -

Typography One Typeface Classification Why Classify?

Typography One typeface classification Why classify? Classification helps us describe and navigate type choices Typeface classification helps to: 1. sort type (scholars, historians, type manufacturers), 2. reference type (educators, students, designers, scholars) Approximately 250,000 digital typefaces are available today— Even with excellent search engines, a common system of description is a big help! classification systems Many systems have been proposed Francis Thibaudeau, 1921 Maximillian Vox, 1952 Vox-ATypI, 1962 Aldo Novarese, 1964 Alexander Lawson, 1966 Blackletter Venetian French Dutch-English Transitional Modern Sans Serif Square Serif Script-Cursive Decorative J. Ben Lieberman, 1967 Marcel Janco, 1978 Ellen Lupton, 2004 The classification system you will learn is a combination of Lawson’s and Lupton’s systems Black Letter Old Style serif Transitional serif Modern Style serif Script Cursive Slab Serif Geometric Sans Grotesque Sans Humanist Sans Display & Decorative basic characteristics + stress + serifs (or lack thereof) + shape stress: where the thinnest parts of a letter fall diagonal stress vertical stress no stress horizontal stress Old Style serif Transitional serif or Slab Serif or or reverse stress (Centaur) Modern Style serif Sans Serif Display & Decorative (Baskerville) (Helvetica) (Edmunds) serif types bracketed serifs unbracketed serifs slab serifs no serif Old Style Serif and Modern Style Serif Slab Serif or Square Serif Sans Serif Transitional Serif (Bodoni) or Egyptian (Helvetica) (Baskerville) (Rockwell/Clarendon) shape Geometric Sans Serif Grotesk Sans Serif Humanist Sans Serif (Futura) (Helvetica) (Gill Sans) Geometric sans are based on basic Grotesk sans look precisely drawn. Humanist sans are based on shapes like circles, triangles, and They have have uniform, human writing. -

15 the Effect of Font Type on Screen Readability by People with Dyslexia

The Effect of Font Type on Screen Readability by People with Dyslexia LUZ RELLO and RICARDO BAEZA-YATES, Web Research Group, DTIC, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain Around 10% of the people have dyslexia, a neurological disability that impairs a person’s ability to read and write. There is evidence that the presentation of the text has a significant effect on a text’s accessibility for people with dyslexia. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no experiments that objectively 15 measure the impact of the typeface (font) on screen reading performance. In this article, we present the first experiment that uses eye-tracking to measure the effect of typeface on reading speed. Using a mixed between-within subject design, 97 subjects (48 with dyslexia) read 12 texts with 12 different fonts. Font types have an impact on readability for people with and without dyslexia. For the tested fonts, sans serif , monospaced, and roman font styles significantly improved the reading performance over serif , proportional, and italic fonts. On the basis of our results, we recommend a set of more accessible fonts for people with and without dyslexia. Categories and Subject Descriptors: H.5.2 [Information Interfaces and Presentation]: User Interfaces— Screen design, style guides; K.4.2 [Computers and Society]: Social Issues—Assistive technologies for per- sons with disabilities General Terms: Design, Experimentation, Human Factors Additional Key Words and Phrases: Dyslexia, learning disability, best practices, web accessibility, typeface, font, readability, legibility, eye-tracking ACM Reference Format: Luz Rello and Ricardo Baeza-Yates. 2016. The effect of font type on screen readability by people with Dyslexia. -

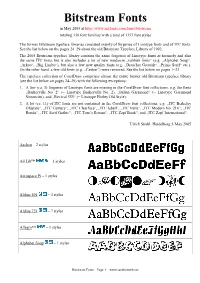

Bitstream Fonts in May 2005 at Totaling 350 Font Families with a Total of 1357 Font Styles

Bitstream Fonts in May 2005 at http://www.myfonts.com/fonts/bitstream totaling 350 font families with a total of 1357 font styles The former Bitstream typeface libraries consisted mainly of forgeries of Linotype fonts and of ITC fonts. See the list below on the pages 24–29 about the old Bitstream Typeface Library of 1992. The 2005 Bitstream typeface library contains the same forgeries of Linotype fonts as formerly and also the same ITC fonts, but it also includes a lot of new mediocre „rubbish fonts“ (e.g. „Alphabet Soup“, „Arkeo“, „Big Limbo“), but also a few new quality fonts (e.g. „Drescher Grotesk“, „Prima Serif“ etc.). On the other hand, a few old fonts (e.g. „Caxton“) were removed. See the list below on pages 1–23. The typeface collection of CorelDraw comprises almost the entire former old Bitstream typeface library (see the list below on pages 24–29) with the following exceptions: 1. A few (ca. 3) forgeries of Linotype fonts are missing in the CorelDraw font collections, e.g. the fonts „Baskerville No. 2“ (= Linotype Baskerville No. 2), „Italian Garamond“ (= Linotype Garamond Simoncini), and „Revival 555“ (= Linotype Horley Old Style). 2. A lot (ca. 11) of ITC fonts are not contained in the CorelDraw font collections, e.g. „ITC Berkeley Oldstyle“, „ITC Century“, „ITC Clearface“, „ITC Isbell“, „ITC Italia“, „ITC Modern No. 216“, „ITC Ronda“, „ITC Serif Gothic“, „ITC Tom’s Roman“, „ITC Zapf Book“, and „ITC Zapf International“. Ulrich Stiehl, Heidelberg 3-May 2005 Aachen – 2 styles Ad Lib™ – 1 styles Aerospace Pi – 1 styles Aldine -

Afgbaskerville (The Type Face)

gfaBaskerville (the type face) xagfi {the type} {the man} abcdefghijklmn opqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHI JKLMNOPQR STUVWXYZ Having been an early admirer of the beauty of letters, I vertical stress relatively low contrast “became insensibly desirous of contributing to the perfection Baskerville is a transitional type of them. I formed to myself ideas of greater accuracy than had yet appeared, and had endeavoured to produce a set of types according to what I conceived to be their true { old style type modern type proportion. oblique stress vertical stress —John Baskerville, preface to Milton, 1758 relatively low contrast high contrast (Anatomy of a Typeface) ” {looks} use of orthogonal lines use of orthogonal + curvy lines FHTt BDp use of curvy lines use of diagonal lines cOQ vwXZ In order to truely appreciate the quialities of Baskerville, one must understand the The Baskerville type is known for the crisp edges, high contrast and generous process of its creation. Being a printer, John Baskerville paid close attention to the proportions. Baskerville is categorized as a transitional typeface in between classical technology, creating his own intense black ink. He boiled fine linseed oil to a certain typefaces and the high contrast modern faces. density, dissolved rosin, and let it subside for months before using it. He also studied and invested in presses, resulting in the development of high standards for presses altogether. {anatomy} crossbar serif ear head serif ascender counter apex A a x g Q b q O spur x-height descender swash {characteristics} {1}g Q {2} A {3} {4}J {5}C {6}E {7}ea {1} tail on lower case g does not close {2} swash-like tail of Q {4} J well below baseline {3} high crossbar and pointed apex of A {5} top and bottom serifs on C {6} long lower arm of E {7} small counter of italic e compared to italic a {comparison} Bembo Baskerville Bembo Baskerville d The head serif of Baskerville is generally more horizontal than that of Bembo. -

Basic Styles of Lettering for Monuments and Markers.Indd

BASIC STYLES OF LETTERING FOR MONUMENTS AND MARKERS Monument Builders of North America, Inc. AA GuideGuide ToTo TheThe SelectionSelection ofof LETTERINGLETTERING From primitive times, man has sought to crude or garish or awkward letters, but in communicate with his fellow men through letters of harmonized alphabets which have symbols and graphics which conveyed dignity, balance and legibility. At the same meaning. Slowly he evolved signs and time, they are letters which are designed to hieroglyphics which became the visual engrave or incise cleanly and clearly into expression of his language. monumental stone, and to resist change or obliteration through year after year of Ultimately, this process evolved into the exposure. writing and the alphabets of the various tongues and civilizations. The early scribes The purpose of this book is to illustrate the and artists refi ned these alphabets, and the basic styles or types of alphabets which have development of printing led to the design been proved in memorial art, and which are of alphabets of related character and ready both appropriate and practical in the lettering readability. of monuments and markers. Memorial art--one of the oldest of the arts- Lettering or engraving of family memorials -was among the fi rst to use symbols and or individual markers is done today with “letters” to inscribe lasting records and history superb fi delity through the use of lasers or the into stone. The sculptors and carvers of each sandblast process, which employs a powerful generation infl uenced the form of letters and stream or jet of abrasive “sand” to cut into the numerals and used them to add both meaning granite or marble. -

Powerpoint 2007

Office 2007 Microsoft Office Fluent User Interface ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Key Components ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 The Office Button .................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 The Ribbon .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Contextual Tabs ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Galleries .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Live Preview ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Mini Toolbar .......................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Presentation

Born Broken: Fonts And Information Loss In Legacy Documents Geoffrey Brown and Kam Woods Indiana University School of Informatics and Computing Key Questions How pervasive are font substitution problems ? What information is available to identify fonts ? How well can we match the fonts required by a document collection ? How can we assist archivists in identifying serious font issues ? Page 8 MCTM Bulletin February 2005 K: I knew what you meant. I was just kidding. I’ll do XüLLbl (W):InputQ:FnOff :"""Y =! Y",Y#:PlotsOff the dishes tonight at dinner. YüL‚(W):Goto:0!Xscl:0!Yscl:Plot1(Scatt T er,L#,L$,&) PlotsOn 1:ZoomStat:StorePic Pic1 Lbl Q:FnOff :""üY :PlotsOff Jennifer felt better so offered the following challenge to Pause :Goto T Kevin. Lbl:0üXscl:0üYscl:Plot1(Scatt S:ClrHome:2!dim(L%er,L):dim(L ,L‚,Ñ)# )!N J: What type of general statement can you make DispPlotsOn "NO. 1:ZoomStat:StorePic OF Pic1 regarding the various polygons and, better yet, what PausePTS.":Output(1,13,N):Pause :Goto T can you say about a figure that looks like this? LblFor(I,1,N):ClrHome S:ClrHome:2üdim(Lƒ):dim(L )üN Disp "NO. "PT. OF NO.","":Output(1,9,I) PTS.":Output(1,13,N):Pause L#(I)!L%(1):L$(I)!L%(2) For(I,1,N):ClrHome Disp L%:Pause :End:Goto T LblDisp "PT.0:Menu(" NO.","":Output(1,9,I) MODELS R""," LINEAR (2)",1,"L(I)üLƒ(1):L‚(I)üLƒ(2) QUADRATIC",2," CUBIC/QUARTIC",3,"Disp Lƒ:Pause :End:Goto LOGARITHMIC",4," T LblEXPONENTIAL",5," 0:Menu(" MODELS POWER",6," RÜ"," LINEAR MAIN (2)",1," MENU",T) QUADRATIC",2," CUBIC/QUARTIC",3," Lbl 1:"aX+b"!Y# Kevin was impressed. -

A Baylor-Healthtexas Affiliate Practice Name

2 HealthTexas Communications Guide | Logo Guidelines Physician Practice Logo Guidelines Practice Name ABaylor-HealthTexas Affiliate Logos and stationery for HealthTexas physi- cian practices are designed to complement those of Baylor Health Care System, visually PRACTICE NAME reinforcing our relationship with the Baylor brand. The practice name is emphasized through the use of large type and color. The typeface and In addition, the consistency in design and the color is the same as the Baylor Health Care color visually link together physician prac- System logo. The blue ink is PMS 300. tices which do not share a common name. AFFILIATE LINE This information uses the Baylor flame icon and text to document the affiliate relationship between Baylor and HTPN. The style of this type is the same as the Baylor logo. To the left are examples of practices within the HTPN organization. The third example is a Baylor branded practice name, so the Baylor flame icon and Baylor logotype are used. Color Guidelines The practice logo is printed in PMS 300 blue and black for most stationery items. It can also be printed in all blue, all black, or reversed to white as shown below. Practice Name ABaylor-HealthTexas Affiliate Practice Name ABaylor-HealthTexas Affiliate Practice Name ABaylor-HealthTexas Affiliate 3 HealthTexas Communications Guide | Logo Guidelines Logo Misuses Typography The logo may not be recreated or used inconsistently with the Baylor The following are approved fonts and Baylor-HealthTexas Affiliate logo guidelines. Unacceptable uses for use in printed materials such include improper color usage or changes to the typography. Consis- as ads, brochures and newslet- tency with the graphic standards helps protect the Baylor-HealthTexas ters.