Calligraphic Tendencies in the Development of Sanserif Types in the Twentieth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dubrovnik Manuscripts and Fragments Written In

Rozana Vojvoda DALMATIAN ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPTS WRITTEN IN BENEVENTAN SCRIPT AND BENEDICTINE SCRIPTORIA IN ZADAR, DUBROVNIK AND TROGIR PhD Dissertation in Medieval Studies (Supervisor: Béla Zsolt Szakács) Department of Medieval Studies Central European University BUDAPEST April 2011 CEU eTD Collection TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 7 1.1. Studies of Beneventan script and accompanying illuminations: examples from North America, Canada, Italy, former Yugoslavia and Croatia .................................................................................. 7 1.2. Basic information on the Beneventan script - duration and geographical boundaries of the usage of the script, the origin and the development of the script, the Monte Cassino and Bari type of Beneventan script, dating the Beneventan manuscripts ................................................................... 15 1.3. The Beneventan script in Dalmatia - questions regarding the way the script was transmitted from Italy to Dalmatia ............................................................................................................................ 21 1.4. Dalmatian Benedictine scriptoria and the illumination of Dalmatian manuscripts written in Beneventan script – a proposed methodology for new research into the subject .............................. 24 2. ZADAR MANUSCRIPTS AND FRAGMENTS WRITTEN IN BENEVENTAN SCRIPT ............ 28 2.1. Introduction -

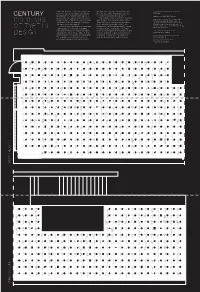

Century 100 Years of Type in Design

Bauhaus Linotype Charlotte News 702 Bookman Gilgamesh Revival 555 Latin Extra Bodoni Busorama Americana Heavy Zapfino Four Bold Italic Bold Book Italic Condensed Twelve Extra Bold Plain Plain News 701 News 706 Swiss 721 Newspaper Pi Bodoni Humana Revue Libra Century 751 Boberia Arriba Italic Bold Black No.2 Bold Italic Sans No. 2 Bold Semibold Geometric Charlotte Humanist Modern Century Golden Ribbon 131 Kallos Claude Sans Latin 725 Aurora 212 Sans Bold 531 Ultra No. 20 Expanded Cockerel Bold Italic Italic Black Italic Univers 45 Swiss 721 Tannarin Spirit Helvetica Futura Black Robotik Weidemann Tannarin Life Italic Bailey Sans Oblique Heavy Italic SC Bold Olbique Univers Black Swiss 721 Symbol Swiss 924 Charlotte DIN Next Pro Romana Tiffany Flemish Edwardian Balloon Extended Bold Monospaced Book Italic Condensed Script Script Light Plain Medium News 701 Swiss 721 Binary Symbol Charlotte Sans Green Plain Romic Isbell Figural Lapidary 333 Bank Gothic Bold Medium Proportional Book Plain Light Plain Book Bauhaus Freeform 721 Charlotte Sans Tropica Script Cheltenham Humana Sans Script 12 Pitch Century 731 Fenice Empire Baskerville Bold Bold Medium Plain Bold Bold Italic Bold No.2 Bauhaus Charlotte Sans Swiss 721 Typados Claude Sans Humanist 531 Seagull Courier 10 Lucia Humana Sans Bauer Bodoni Demi Bold Black Bold Italic Pitch Light Lydian Claude Sans Italian Universal Figural Bold Hadriano Shotgun Crillee Italic Pioneer Fry’s Bell Centennial Garamond Math 1 Baskerville Bauhaus Demian Zapf Modern 735 Humanist 970 Impuls Skylark Davida Mister -

Donald Jackson

Donald Jackson Calligrapher Artistic Director Donald Jackson was born in Lancashire, England in 1938 and is considered one of the world's foremost Western calligraphers. At the age of 13, he won a scholarship to art school where he spent six years studying drawing, painting, design and the traditional Western calligraphy and illuminating. He completed his post-graduate specialization in London. From an early age he sought to combine the use of the ancient techniques of the calligrapher's art with the imaginary and spontaneous letter forms of his own time. As a teenager his first ambition was to be "The Queen's Scribe" and a close second was to inscribe and illuminate the Bible. His talents were soon recognized. At the age of 20, while still a student himself, he was appointed a visiting lecturer (professor) at the Camberwell College of Art, London. Within six years he became the youngest artist calligrapher chosen to take part in the Victoria and Albert Museum's first International Calligraphy Show after the war and appointed a scribe to the Crown Office at the House of Lords. In other words, he became "The Queen's Scribe." Since then, in conjunction with a wide range of other calligraphic projects, he has continued to execute Historic Royal documents including Letters Patent under The Great Seal and Royal Charters. He was decorated by the Queen with the Medal of The Royal Victorian Order (MVO) which is awarded for personal services to the Sovereign in 1985. Jackson is an elected Fellow and past Chairman of the prestigious Society of Scribes and Illuminators, and in 1997, Master of 600-year-old Guild of Scriveners of the city of London. -

Fritz Kredel, Woodcutter and Book Illustrator, Hermann Zapf

— 1 >vN^ MOIiniliSNI_NVINOSHilWS S3 I d VH 8 n_LI B RAR I ES SMlTHSONlAN_INSTn LI B RAR I Es'^SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION o XI _ z NoiiniiiSNrNviNOSHiiws~s3iyvyan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniiisNi nvinoshiiws S3ia libraries smithsonian~institution NoiiniiiSNi nvinoshiiws S3iyvyan libraries Smithsonian insti N0linillSNrNVlN0SHilWs'^S3 IdVHan^LIBRARI ES*"sMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIifliliSNI NVIN0SHllWs'"s3 1 libraries SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIiniUSNI NVmOSHilWS S3iavaan LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTI -^ — z (^ — 2 u) £ w ^ </> NOIifliliSNI NVINOSHimS SBiyvyaiT libraries SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIifliliSNI NVINOSHIIWS S3 1 i: TUTiON Noiin±iiSNi_MviNOSHiiws saiavyan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniiisNi nvinoshii ^ y> ^ tn - to = , . _. 2 \ ^ 5 vaan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniiiSNi nvinoshiiims S3iavaan libraries smithsoni •- 2 ^ ^ ^ z r- 2 t- z TUTION NOIinillSNl NVINOSHIIIMStfiN0SHiiiMS^S3S3iaVyaniavyan~LiBRARilibrarieses^smithsonian'instituiSMITHSONIAN institution NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHil w ..-. </> V. (rt z 2 2 V C" z * 2 W 2 CO •2 J^ 2 W Vaan_l-IBRARIES SMITHS0NIAN_INSTITUTI0N NOIJ.nillSNI_NVINOSHillMS S3lbVaan_LIBRARIES SMITHSONI/ 2 __ _ _ _ ruTioN NOIiniliSNI NViNosHiiws S3iyvaan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniiiSNi''NviNOSHiii/ ^S^TlfS^ ^A 3 fe; /^ KREDEL ZAPF THE COOPER UNION MUSEUM FOR THE ARTS OF DECORATION A JOINT EXHIBITION AT THE COOPER UNION MUSEUM FOR THE ARTS OF DECORATION • COOPER SQUARE AT 7TH STREET. NEW YORK FRITZ KREDEL woodcutter and book illustrator HERMANN ZAPF calligrapher and type designer MONDAY 15 OCTOBER UNTIL THURSDAY 25 OCTOBER 1951 MUSEUM HOURS: MONDAY THROUGH SATURDAY, 10 A. M. TO 5 P. M. • TUESDAY AND THURSDAY EVENINGS UNTIL 9:30 Acknowledgment this display of the work of Mr. Fritz Kredel and Mr. Hermann Zapf, the third to be held in the Museum in recent years in which the graphic arts have figured, reflects at once a growing pubHc interest in the design of books and an increased emphasis placed upon book design in the art training of today. -

Writing As Material Practice Substance, Surface and Medium

Writing as Material Practice Substance, surface and medium Edited by Kathryn E. Piquette and Ruth D. Whitehouse Writing as Material Practice: Substance, surface and medium Edited by Kathryn E. Piquette and Ruth D. Whitehouse ]u[ ubiquity press London Published by Ubiquity Press Ltd. Gordon House 29 Gordon Square London WC1H 0PP www.ubiquitypress.com Text © The Authors 2013 First published 2013 Front Cover Illustrations: Top row (from left to right): Flouda (Chapter 8): Mavrospelio ring made of gold. Courtesy Heraklion Archaelogical Museum; Pye (Chapter 16): A Greek and Latin lexicon (1738). Photograph Nick Balaam; Pye (Chapter 16): A silver decadrachm of Syracuse (5th century BC). © Trustees of the British Museum. Middle row (from left to right): Piquette (Chapter 11): A wooden label. Photograph Kathryn E. Piquette, courtesy Ashmolean Museum; Flouda (Chapter 8): Ceramic conical cup. Courtesy Heraklion Archaelogical Museum; Salomon (Chapter 2): Wrapped sticks, Peabody Museum, Harvard. Photograph courtesy of William Conklin. Bottom row (from left to right): Flouda (Chapter 8): Linear A clay tablet. Courtesy Heraklion Archaelogical Museum; Johnston (Chapter 10): Inscribed clay ball. Courtesy of Persepolis Fortification Archive Project, Oriental Institute, University of Chicago; Kidd (Chapter 12): P.Cairo 30961 recto. Photograph Ahmed Amin, Egyptian Museum, Cairo. Back Cover Illustration: Salomon (Chapter 2): 1590 de Murúa manuscript (de Murúa 2004: 124 verso) Printed in the UK by Lightning Source Ltd. ISBN (hardback): 978-1-909188-24-2 ISBN (EPUB): 978-1-909188-25-9 ISBN (PDF): 978-1-909188-26-6 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/bai This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. -

Consuming Fashions: Typefaces, Ubiquity and Internationalisation

CONSUMING FASHIONS: TYPEFACES, UBIQUITY AND INTERNATIONALISATION Anthony Cahalan School of Design and Architecture University of Canberra ACT ABSTRACT Typefaces are essential to a designer’s ability to communicate visually. The late twentieth century witnessed the democratisation and internationalisation of typeface design and usage due to the ease of access to desktop computer technology and a related exponential growth in the number of typefaces available to users of type. In this paper, theories of fashion, consumption and material culture are used to explain and understand this phenomenon of the proliferation of typefaces. Theories are explored from outside art and design to position typeface designing as an activity, and typefaces as artefacts, within a more comprehensive societal picture than the expected daily professional practice of graphic designers and everyday computer users. This paper also shows that by tracking and thereby understanding the cultural significance of ubiquitous typefaces, it is possible to illustrate the effects of internationalisation in the broader sphere of art and design. CONSUMING FASHIONS: TYPEFACES, UBIQUITY AND INTERNATIONALISATION Technological and stylistic developments in the design, use and reproduction of text since the invention of the alphabet three-and-a-half thousand years ago were exponential in the last two decades of the twentieth century, due significantly to the ready access of designers to the desktop computer and associated software. The parallels between fashion and typefaces—commonly called ‘fonts’— are explored in this paper, with particular reference to theories of fashion, consumption and material culture. This represents the development of a theoretical framework which positions typeface design as an activity, and typefaces as artefacts, within a broader societal picture than the expected daily professional practice of graphic designers and everyday computer users. -

Gotische Schrift

l Gutenberg l Gotische Schrift l Schwabacher l Fraktur l Renaissance-Antiqua l Barock-Antiqua l Klassizistische Antiqua l Egyptienne l Grotesk l Jugendstil DIE ENTWICKLUNG DER DRUCKSCHRIFTEN l Johannes Gensfleisch, genannt Gutenberg * um 1400 in Mainz † 1468 ebenda Mit Gutenbergs Erfindung des Buchdrucks mit beweglichen Metalllettern und der Druckerpresse begann eine ganz neue Epoche. Die Verwendung der beweglichen Lettern ab 1450 revolutionierte die her- kömmliche Methode der Buchproduktion (Handschriften). Der Buchdruck breitete sich schnell in Europa und später in der ganzen Welt aus. Es begann die große Zeit der Entwicklung der Druckschriften. Im deutschsprachigen Raum setzten sich die gebrochenen Schrif- ten durch: Textura (Gotisch), Schwabacher, Fraktur und Kanzlei. Im italienischen Sprachraum konnte sich die gotische Schrift nicht durchsetzen. Dort entstand um 1300 die Rotunda oder Rundgotisch, eine offene Schrift von guter Lesbarkeit und Vorläufer der Antiqua-Schriften. GEBROCHENE SCHRIFTEN l Gotische Schrift (1300 – 1450) Von der Normandie breitete sich in Frank- reich ein neuer Stil aus: die Gotik. Dem Baustil entsprechend war auch die Schrift kantig und hochaufragend, das Schriftbild wirkte eng und düster. Damals bestimmte der christliche Glaube maßgebend das Leben und Kunstschaffen. Die Schrift der Zeit, die Textura, wurde ihrer würdevollen Form wegen hauptsäch- lich für liturgische Bücher verwendet. Auch Gutenberg schnitt seine Typen in dieser Schrift für seine Bibel. Daneben entwickelten sich die gotischen Buchkursiven mit ihren teilweise verschleif- ten Formen von großer Lebendigkeit. GEBROCHENE SCHRIFTEN l Schwabacher (1400) Im 15. Jhd. entstand durch die Vermi- schung der Textura mit der gotischen Kursivschrift die gut lesbare Schwabacher mit ihren offenen Formen. Der derbe Charakter brachte ihr gro- ße Beliebtheit und sie wurde bald zur meistgedruckten Schrift der volkstümlichen Literatur. -

Typographic Design: Form and Communication

Typographic Design: Form and Communication Fifth Edition Saint Barbara. Polychromed walnut sculpture, fifteenth- century German or French. The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Typographic Design: Form and Communication Fifth Edition Rob Carter Ben Day Philip Meggs JOHN WILEY & SONS, INC. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Copyright © 2012 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750- 8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or on-line at www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. -

The Impact of the Historical Development of Typography on Modern Classification of Typefaces

M. Tomiša et al. Utjecaj povijesnog razvoja tipografije na suvremenu klasifikaciju pisama ISSN 1330-3651 (Print), ISSN 1848-6339 (Online) UDC/UDK 655.26:003.2 THE IMPACT OF THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF TYPOGRAPHY ON MODERN CLASSIFICATION OF TYPEFACES Mario Tomiša, Damir Vusić, Marin Milković Original scientific paper One of the definitions of typography is that it is the art of arranging typefaces for a specific project and their arrangement in order to achieve a more effective communication. In order to choose the appropriate typeface, the user should be well-acquainted with visual or geometric features of typography, typographic rules and the historical development of typography. Additionally, every user is further assisted by a good quality and simple typeface classification. There are many different classifications of typefaces based on historical or visual criteria, as well as their combination. During the last thirty years, computers and digital technology have enabled brand new creative freedoms. As a result, there are thousands of fonts and dozens of applications for digitally creating typefaces. This paper suggests an innovative, simpler classification, which should correspond to the contemporary development of typography, the production of a vast number of new typefaces and the needs of today's users. Keywords: character, font, graphic design, historical development of typography, typeface, typeface classification, typography Utjecaj povijesnog razvoja tipografije na suvremenu klasifikaciju pisama Izvorni znanstveni članak Jedna je od definicija tipografije da je ona umjetnost odabira odgovarajućeg pisma za određeni projekt i njegova organizacija s ciljem ostvarenja što učinkovitije komunikacije. Da bi korisnik mogao odabrati pravo pismo za svoje potrebe treba prije svega dobro poznavati optičke ili geometrijske značajke tipografije, tipografska pravila i povijesni razvoj tipografije. -

Zapfcoll Minikatalog.Indd

Largest compilation of typefaces from the designers Gudrun and Hermann Zapf. Most of the fonts include the Euro symbol. Licensed for 5 CPUs. 143 high quality typefaces in PS and/or TT format for Mac and PC. Colombine™ a Alcuin™ a Optima™ a Marconi™ a Zapf Chancery® a Aldus™ a Carmina™ a Palatino™ a Edison™ a Zapf International® a AMS Euler™ a Marcon™ a Medici Script™ a Shakespeare™ a Zapf International® a Melior™ a Aldus™ a Melior™ a a Melior™ Noris™ a Optima™ a Vario™ a Aldus™ a Aurelia™ a Zapf International® a Carmina™ a Shakespeare™ a Palatino™ a Aurelia™ a Melior™ a Zapf book® a Kompakt™ a Alcuin™ a Carmina™ a Sistina™ a Vario™ a Zapf Renaissance Antiqua® a Optima™ a AMS Euler™ a Colombine™ a Alcuin™ a Optima™ a Marconi™ a Shakespeare™ a Zapf Chancery® Aldus™ a Carmina™ a Palatino™ a Edison™ a Zapf international® a AMS Euler™ a Marconi™ a Medici Script™ a Shakespeare™ a Zapf international® a Aldus™ a Melior™ a Zapf Chancery® a Kompakt™ a Noris™ a Zapf International® a Car na™ a Zapf book® a Palatino™ a Optima™ Alcuin™ a Carmina™ a Sistina™ a Melior™ a Zapf Renaissance Antiqua® a Medici Script™ a Aldus™ a AMS Euler™ a Colombine™ a Vario™ a Alcuin™ a Marconi™ a Marconi™ a Carmina™ a Melior™ a Edison™ a Shakespeare™ a Zapf book® aZapf international® a Optima™ a Zapf International® a Carmina™ a Zapf Chancery® Noris™ a Optima™ a Zapf international® a Carmina™ a Sistina™ a Shakespeare™ a Palatino™ a a Kompakt™ a Aurelia™ a Melior™ a Zapf Renaissance Antiqua® Antiqua® a Optima™ a AMS Euler™ a Introduction Gudrun & Hermann Zapf Collection The Gudrun and Hermann Zapf Collection is a special edition for Macintosh and PC and the largest compilation of typefaces from the designers Gudrun and Hermann Zapf. -

Fonturi Sans Serif Sau Fonturi Cu Serife?

Fonturi sans serif sau fonturi cu serife? Disputa serif versus sans serif este una epică. Ca și în cazurile Mac vs. PC, Adidas vs. Nike, Cola vs. Pepsi, etc. există argumente pro și contra, diferențe de gusturi și opinii, dar niciuna dintre părți nu deține adevărul absolut. Aflați în cele ce urmează mai multe despre cele două tipuri de fonturi și câteva sfaturi de folosire a lor. Fonturile cu serife Fonturile cu serife își au originea în alfabetul roman inventat în timpul Imperiului Roman, exemplul clasic fiind majusculele de pe coloana lui Traian (113 e.n.), deși primele inscripții cu caractere cu serife provin din Grecia antică (secolele IV-II î.e.n.). Originea lor nu este stabilită clar: Edward Catich, în studiul său, “The Origin of the Serif”, consideră că serifele sunt o rămășiță a procesului de pictare a literelor pe piatră înainte de sculptarea efectivă cu dalta. Originea cuvântului în sine nu este clară, cele mai credibile explicații fiind cea din Dictionarul Oxford de Limba Engleză potrivit căruia cuvântul s-a format dupa apariția lui “sanserif”, citat în Dictionarul Oxford în 1841 și cea oferită de un al doilea dictionar, Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, care leagă noțiunea de cuvântul “schreef” care în olandeză înseamnă “linie” sau “semn de peniță”. Clasificarea pe scurt a fonturilor cu serife (old style, transitional, modern, latin serif și slab serif) o puteți reciti în articolul “Type, typeface și tipuri de fonturi” (http://typography.ro/2008/11/23/type-typeface-si-tipuri-de-fonturi/), dar o voi relua și în cele ce urmează mai detaliat: Old Style: apărute în secolele al XV-lea și al XVI-lea în timpul Renașterii, au avut drept inspirație inițialele romane și minuscula carolingiană, motiv pentru care se mai numesc și “anticve” sau “antique”, termen folosit de altfel pentru toate fonturile create după epoca “Blackletter”. -

TEX Support for the Fontsite 500 Cd 30 May 2003 · Version 1.1

TEX support for the FontSite 500 cd 30 May 2003 · Version 1.1 Christopher League Here is how much of TeX’s memory you used: 3474 strings out of 12477 34936 string characters out of 89681 55201 words of memory out of 263001 3098 multiletter control sequences out of 10000+0 1137577 words of font info for 1647 fonts, out of 2000000 for 2000 Copyright © 2002 Christopher League [email protected] Permission is granted to make and distribute verbatim copies of this manual provided the copyright notice and this permission notice are preserved on all copies. The FontSite and The FontSite 500 cd are trademarks of Title Wave Studios, 3841 Fourth Avenue, Suite 126, San Diego, ca 92103. i Table of Contents 1 Copying ........................................ 1 2 Announcing .................................... 2 User-visible changes ..................................... 3 3 Installing....................................... 5 3.1 Find a suitable texmf tree............................. 5 3.2 Copy files into the tree .............................. 5 3.3 Tell drivers how to use the fonts ...................... 6 3.4 Test your installation ................................ 7 3.5 Other applications .................................. 8 3.6 Notes for Windows users ............................ 9 3.7 Notes for Mac users................................. 9 4 Using ......................................... 10 4.1 With TeX ........................................ 10 4.2 Accessing expert sets ............................... 11 4.3 Using CombiNumerals ............................