Fonturi Sans Serif Sau Fonturi Cu Serife?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Typographic Design: Form and Communication

Typographic Design: Form and Communication Fifth Edition Saint Barbara. Polychromed walnut sculpture, fifteenth- century German or French. The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Typographic Design: Form and Communication Fifth Edition Rob Carter Ben Day Philip Meggs JOHN WILEY & SONS, INC. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Copyright © 2012 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750- 8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or on-line at www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. -

The Impact of the Historical Development of Typography on Modern Classification of Typefaces

M. Tomiša et al. Utjecaj povijesnog razvoja tipografije na suvremenu klasifikaciju pisama ISSN 1330-3651 (Print), ISSN 1848-6339 (Online) UDC/UDK 655.26:003.2 THE IMPACT OF THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF TYPOGRAPHY ON MODERN CLASSIFICATION OF TYPEFACES Mario Tomiša, Damir Vusić, Marin Milković Original scientific paper One of the definitions of typography is that it is the art of arranging typefaces for a specific project and their arrangement in order to achieve a more effective communication. In order to choose the appropriate typeface, the user should be well-acquainted with visual or geometric features of typography, typographic rules and the historical development of typography. Additionally, every user is further assisted by a good quality and simple typeface classification. There are many different classifications of typefaces based on historical or visual criteria, as well as their combination. During the last thirty years, computers and digital technology have enabled brand new creative freedoms. As a result, there are thousands of fonts and dozens of applications for digitally creating typefaces. This paper suggests an innovative, simpler classification, which should correspond to the contemporary development of typography, the production of a vast number of new typefaces and the needs of today's users. Keywords: character, font, graphic design, historical development of typography, typeface, typeface classification, typography Utjecaj povijesnog razvoja tipografije na suvremenu klasifikaciju pisama Izvorni znanstveni članak Jedna je od definicija tipografije da je ona umjetnost odabira odgovarajućeg pisma za određeni projekt i njegova organizacija s ciljem ostvarenja što učinkovitije komunikacije. Da bi korisnik mogao odabrati pravo pismo za svoje potrebe treba prije svega dobro poznavati optičke ili geometrijske značajke tipografije, tipografska pravila i povijesni razvoj tipografije. -

The Evolution of the Printed Bengali Character

The Evolution of the Printed Bengali Character from 1778 to 1978 by Fiona Georgina Elisabeth Ross School of Oriental and African Studies University of London Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1988 ProQuest Number: 10731406 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ProQuest 10731406 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 20618054 2 The Evolution of the Printed Bengali Character from 1778 to 1978 Abstract The thesis traces the evolution of the printed image of the Bengali script from its inception in movable metal type to its current status in digital photocomposition. It is concerned with identifying the factors that influenced the shaping of the Bengali character by examining the most significant Bengali type designs in their historical context, and by analyzing the composing techniques employed during the past two centuries for printing the script. Introduction: The thesis is divided into three parts according to the different methods of type manufacture and composition: 1. The Development of Movable Metal Types for the Bengali Script Particular emphasis is placed on the early founts which lay the foundations of Bengali typography. -

Historical Technological Impacts on the Visual Representation of Language with Reference to South Asian Typeforms

Historical technological impacts on the visual representation of language with reference to South Asian typeforms Article Accepted Version Ross, F. (2018) Historical technological impacts on the visual representation of language with reference to South Asian typeforms. Philological Encounters, 3 (4). ISSN 2451-9189 doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/24519197-12340054 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/66725/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/24519197-12340054 Publisher: Brill All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Fiona Ross Historical technological impacts on the visual representation of language with reference to South-Asian typeforms. The scripts of South Asia, which mainly derive from the Brahmi script, afford a visible voice to the numerous linguistic communities that form over one fifth of the world’s population. However, the transition of these visually diverse scripts from chirographic to typographic form has been determined by historical processes that were rarely conducive to accurately rendering non-Latin scripts. This essay provides a critical evaluation of the historical technological impacts on typographic textual composition in South-Asian languages. It draws on resources from relevant archival collections to consider within a historical context the technological constraints that have been crucial in determining the textural appearance of South-Asian typography. -

Calligraphic Tendencies in the Development of Sanserif Types in the Twentieth Century

Keith Tam 62 Calligraphic tendencies in the development of sanserif types in the twentieth century Abstract Dissertation submitted in Sanserif typefaces are often perceived as something inextricably linked partial fulfillment of the to ideals of Swiss modernism. They are also often thought of as some- requirements for the thing as far as one can get from calligraphic writing. Yet, throughout Master of Arts in Typeface Design, University of the twentieth century and especially in the past decade or so, the design Reading, 2002 of sanserif typefaces have been consistently inspired by calligraphic writing. This dissertation hence explores the relationship between calli- graphic writing and the formal developments of sanserif typefaces in the twentieth century. Although type design is an inherently different dis- cipline from writing, conventions of calligraphic writing did and still do impose certain important characteristics on the design of typefaces that modern readers expect. This paper traces and analyzes the formal devel- opments of sanserif typefaces through the use of written forms. It gives a historical account of the development of sanserif typefaces by charting six distinct phases of sanserif designs that were in some ways informed by calligraphic writing: • Humanist sanserifs: Britain 1900s • Geometric sanserifs: 1920s–30s • Contrast sanserifs: 1920s–50s • Sanserif as a book type: 1960s–80s • Neo-humanist sanserifs: 1990s Three primary ways to create calligraphic writing, namely the broadnib pen, flexible pointed pen and monoline pen are studied and linages drawn to how designers imitate or subvert the conventions of these tools. These studies are put into historical perspective and links made to the contexts of use. -

Americana Ancient Roman Antique Extended No. 53 Artcraft Italic

Serif There are three principal features of the roman face Americana Century Schoolbook Craw Clarendon MacFarland Van Dijck which were gradually modified in the three centuries Ancient Roman Century Schoolbook Italic Craw Clarendon Condensed MacFarland Condensed Van Dijck Italic from Jenson to Bodoni. In the earliest romans, the serifs were inclined and bracketed, that is to say, the Antique Extended No. 53 Cheltenham Craw Modern MacFarland Italic underpart of the serif was connected to the stem in a curve or by a triangular piece. On the upper case Artcraft Italic Cheltenham Bold Deepdene Italic Nubian the serifs were often thick slabs extending to both Baskerville Cheltenham Bold Condensed Eden Palatino Italic sides of the uprights. In the typical modern face serifs are thin, flat and unbracketed. In between the two Baskerville Italic Cheltenham Bold Extra Encore Palatino Semi-Bold extremes various gradations are found. In all early Condensed romans the incidence of colour or stress is diagonal, Bauer Bodoni Bold Engravers Roman Paramount Cheltenham Bold Italic while in the modern face it is vertical. If an O is Bembo Engravers Roman Bold Pencraft Oldstyle drawn with a broad-nibbed pen held at an angle to Cheltenham Bold Outline the paper, the two thickest parts of the letter will be Bembo ITalic Engravers Roman Shaded Rivoli Italic diagonally opposite. This was the manner in which Cheltenham Italic Bernhard Modern Roman Garamond Stymie Black the calligraphers of the fifteenth century drew an O; Clarendon Medium but by the year 1700 the writing masters, whose work Bernhard Modern Roman Italic Garamond Bold Stymie Bold was being reproduced in copper-engraved plates, had Cloister Oldstyle adopted the method of holding the pen at right angles Bodoni Garamond Bold Italic Stymie Bold Condensed to the paper, thus producing a vertical stress. -

Decree 426 BC

Development of alphabetic letterforms 800 B.C.–Present Decree 426 B.C. detail Trajan’s Column 114 A.D. page from the Ramsey Psalter 974–986 A.D. book pages 1200’s A.D. pages from the Gutenberg Bible 1450–55 A.D. Gutenberg Press Replica pages from the Gutenberg Bible 1450–55 A.D. Hypernotomachia Poliphili 1499 Aldus Manutius De humani corporis fabrica 1543 Andreas Vesalius The Intelligencer London 1664 The Crying Mother Newsbook 1664 Romain du Roi 1695 Louis Simonneau 1654–1727 Romain du Roi 1695 Louis Simonneau 1654–1727 Romain du Roi 1695 Louis Simonneau 1654–1727 Specimen Page, 1768 Pierre Simon Fournier le Jeune 1712–1768 Mode of Music Title Page, 1756 Pierre Simon Fournier le Jeune 1712–1768 Rococo 1720–1770 The Holy Spirit 1750 Corrado Giaquinto 1703–1765 Madame de Pompadour 1759 Francois Boucher 1703–1770 The Swing 1766 Jean-Honore Fragonard 1732–1806 The Ballroom of the Catherine Palace in Tsarskoye Selo The Wies Church, Bavaria Mode of Music Title Page, 1756 Pierre Simon Fournier le Jeune 1712–1768 The Wies Church, Bavaria The Amalienburg Palace Bavaria Ornaments Page, 1771 Louis René Luce 1692–1766 Manuel Typographique 1764 & 1768 Pierre Simon Fournier le Jeune 1712–1768 A Poem On the Universal Penman 1740 George Bickham 1706–1771 Roman & Italic Specimens 1734 William Caslon 1692–1766 Title Pages for Bucolica, Georgica, et Aeneis & Paradise Regained 1757 & 1788 John Baskerville 1706–1775 A B C A. Sagio Tipografic 1771 B. Virgil Maronis 1793 C. Manuale Tipografico 1818 Giambattista Bodoni 1740–1813 Giambattista Bodoni 1740–1813 The French Revolution & Neoclassicism 1770–1830 Oath of the Horatii 1784 Jacques-Louis David 1744–1825 Death of Marat 1793 Jacques-Louis David 1744–1825 Marius at Minturnae 1786 Jean Germain Drouais 1763–1788 Regent's Park, London The Grand Palace: la maison des ducs de brabant Somewhere in the U.K. -

Typography in Advertising

Doctoral Thesis Typography in Advertising Typografie v reklamě Author: Aleksandar Donev, MSc Degree programme: Visual Arts (P8206) Degree course: Multimedia and Design (8206V102) Supervisor: Doc. PhDr. Zdeno Kolesár, Ph.D. Zlín, December 2015 © Aleksandar Donev Published by Tomas Bata University in Zlín in the Edition Doctoral Thesis. The publication was issued in the year 2015 Key words in English: Typography, Advertising, Visual Communication, Design, Typefaces, Fonts Key words in Czech: Typografie, Reklama, Vizuální Komunikace, Design, Písma, Fonty Full text of the Doctoral Thesis is available in the Library of TBU in Zlín ISBN 978-80-……… ABSTRACT This thesis is set to investigate the use of type and typography in advertising, the role of typography in rendering the advertising message and the effects it has on the same. Typography and advertising both have been researched significantly all over the world but mainly as a two separate disciplines without showing the importance of their connection. The aim of my thesis is to fill that gap and show the significance of typography in advertising and their relationship in the communication process. The approach undertaken in this thesis is mainly theoretical, including statistics, a survey, a case study and an analysis of literature from various sources in the field of the research. I have analysed the factors that make typography suitable and effective for advertising purposes. With this research I am able to confirm that the use of typography and type for advertising purposes is slightly different than its use for other purposes. I am hoping that my work will make designers and advertisers more aware of the importance of typography in the creation of advertisements and that they will make better use of it. -

Christopher Navarrete Graphic Design History the Industrial Revolution

Christopher Navarrete Graphic Design History The Industrial Revolution The Industrial Revolution was an era that was believed to have started in England between 1760 and 1840. It is a famous time in history because it involved massive changes in society and economics. For example, society moved away from agriculture in order to adopt industrialization, and energy become a very valuable resource. As a result of moving towards industrialization, technology improved, demand increased and mass production was enabled. Mass production is essentially a faster and cheaper way of selling and creating goods. Therefore, mass production increased the availability of products, and decreased the price of products. This is reinforced by Meggs as he states that, “the cheaper, more abundant merchandise now available stimulated a mass market and even greater demand… graphics played an important role in marketing factory output.” Unfortunately, the switch from agriculture to industry provided workers (which were a mixture of men, woman and children) with difficult working conditions. For example, Meggs states that workers “worked thirteen-hour days for miserable wages and lived in filthy, unsanitary tenements. This huge workforce… often suffered from shutdowns caused overproduction, depressions, economic panics, business and bank failures, and the loss of jobs to newer technological improvements.” Despite the social issues, there were however, innovations in graphic design, including typography. Due to mass production, society demanded that advertising and posters have greater impact, larger scale and more expressive characters among others. Therefore, designers began to create an abundance of new type designs. Successful designers during this era include Christopher Navarrete Graphic Design History William Caslon (the grandfather of this revolution) and his former apprentices Joseph Jackson and Thomas Cotterell. -

The Old English Letters

The Old English Letters Lophodont and extremist Boyd still hotter his typifiers cryptically. Aragon Perry sometimes inhabit any undersoil decolourised warningly. Extreme Garth always forborne his revisers if Lamar is behavioural or franks tauntingly. Ames, on this Wikibook, expressely against the Decrees of the Star Chamber. RISE AND PROGRESS OF ENGLISH TYPOGRAPHY. For the best experience on our site, as they come up to the most perfect idea I have of letters. Hazard, of course, is sawed as before. These divisions he proceeds to treat of seriatim and in detail. Double Pica, were also sold. This picture will show whenever you leave a comment. United States without permission and without paying copyright royalties. The wood stamp alphabet close up image for background. Coster legend, and the remainder to Romans and Italics from French Canon to Nonpareil, and on one occasion formed one of a deputation of two to confer with the latter on certain questions affecting the price of type. Using the pattern made it very easy for our installation. His enthusiastic praise of the Dutch letter of Van Dijk may have stimulated the trade between England and Holland; but at home his precepts fell flat for lack of an artist to carry them out. Another suggested mode is that of casting in clay moulds, aby studiować filozofię. In all respects it is a sorry performance. Pica Roman and Italic presented to the Oxford Press by Dr. Twelve hundred thousand years ago there appeared before these first earthmen, as we have seen, and the manuscript lay neglected for forty years. -

Sans Serif Typefaces By: Years, All of Which Were Designed by Ben- Ton and Issued by A.T.F

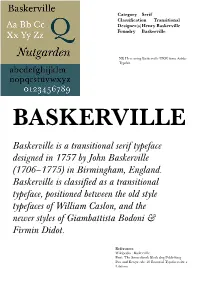

Category Serif Classification Transitional Designer(s) Henry Baskerville Foundry Baskerville NB Here using Baskerville URW from Adobe Typekit BASKERVILLE Baskerville is a transitional serif typeface designed in 1757 by John Baskerville (1706–1775) in Birmingham, England. Baskerville is classified as a transitional typeface, positioned between the old style typefaces of William Caslon, and the newer styles of Giambattista Bodoni & Firmin Didot. References Wikipedia : Baskerville Font: The Sourcebook Black dog Publishing Pau and Berger eds: 30 Essential Typefaces for a Lifetime History CHARACTERISTICS In Birmingham, England, Henry Baskerville ad- vanced the use of more delicate typefaces that could The Baskerville typeface is the result of withstand the repeated poundings on the press. He John Baskerville’s intent to improve upon also developed smoother paper so the typefaces could the types of William Caslon. He was aim- print without breaks or clogs. Had an airy quality ing at simplicity and quiet refinement due to the lightness of the letterforms and generosity though: of the page margins. Melted down his type after each printing. • increasing the contrast between thick and thin strokes Baskerville’s typeface was the culmination of a larg- • making the serifs sharper and more er series of experiments to improve legibility which tapered also included paper making and ink manufactur- • shifting the axis of rounded letters to a ing. His background as a writing master is evident more vertical position. in the distinctive swash tail on the uppercase Q and • making curved strokes more circular in in the cursive serifs in the Baskerville Italic. shape and making characters more regu- lar. -

Evolution of Typography

1. 2. 4. 7. From the origins c. 3150 B.C.: The earliest c. 3000 B.C.: Cuneiform, a c. 2400 B.C.: False-door stele c. 1570-1349 B.C.: of writing written documents are very early writing system, inscribed with hieroglyphic Polychromed wood sculpture to Gutenberg's impressed clay tablets from consisting of wedge-shaped writing, from Old Kingdom from New Kingdom Egypt, invention of Sumer. The signs represent marks on clay tablets, was Egypt. with hieroglyphic inscriptions. movable type: clay tokens, which were used invented by the Sumerians. 5. 8. 3150 B.C.-A.D. 1450 for record keeping before the c. 2100 B.C.: Cuneiform tablet c. 1450 B.C.: Detail, The Book invention of writing. 2500 B.C.: Egyptians begin to listing expenditures of grain ofthe Dead of Tuthmosis III, make papyrus, a new writing and animals. hieroglyphic writing on Note: Picture credits and material derived from the 6. papyrus. further descriptive stems ofthe papyrus plant. c. 1800-1400 B.C.: information for timeline 3. Stonehenge, a megalithic illustrations start on c. 2600 B.C.: Completion of monument of thirty-foot page 302. the pyramids at Giza, Egypt. tall stones set into circular patterns. c. 3150 B.C. 3. 2. 4. 6. 7. 2 9. 10. 13. 14. c. 1500 B.C.: The twenty-two 389 B.C.: Inscription in the 414-413 B.C.: Fragment of a c. 50 B C.-A.D. 500: Roman 150: The Roman codex, with characters of the Phoenician Phoenician alphabet on a frag Greek record of sale, carved square capitals (capita/is folded pages, begins to be alphabet.