The Typeface of Our Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Futura Franklin Gothic

Franklin Gothic Morris Fuller Paul Benton & Renner Futura Futura 1927 Designer Paul Renner created the designed by Renner. Futura has con- typeface Futura in 1927. Futura is a tinued to thrive even to this day with nice geometric sans-serif font, which the help of it’s nice and clean design, unlike typical sans-serif fonts used and is a staple in the typographic in the display world, featured a low world. Young, thriving designers look X-height. Renner wanted to stay to typefaces such as Futura as inspi- away from any decoration when de- ration in the use their own work. signing the font, leaving it with just a crisp and clean typeface. Futura also included some features such as small capitals and old style figures. Renner is a German citizen, so Futura was designed in Germany. Since it’s re- lease, Futura has become one of the most popular fonts, and a common- ly used one for headlines, posters, banners, etc. There have been a few versions that have stemmed off of it’s creation and popularity, including Futura Black, Futura Display, Futu- ra Condensed, and Steile Futura, all Franklin Gothic 1902 Franklin Gothic is a grotesque, over the years. Franklin Gothic is the sans-serif font, designed by Ameri- most popular of the gothic series can designer Morris Fuller Benton in that Benton designed throughout his 1902. Since he was American, nat- career. Due to it’s fame, this typeface urally Franklin Gothic was created is frequently talked about in high in the United States. The typeface is regards in classrooms and schools bolder than a regular font and named where typography history is taught. -

Surviving the TEX Font Encoding Mess Understanding The

Surviving the TEX font encoding mess Understanding the world of TEX fonts and mastering the basics of fontinst Ulrik Vieth Taco Hoekwater · EuroT X ’99 Heidelberg E · FAMOUS QUOTE: English is useful because it is a mess. Since English is a mess, it maps well onto the problem space, which is also a mess, which we call reality. Similary, Perl was designed to be a mess, though in the nicests of all possible ways. | LARRY WALL COROLLARY: TEX fonts are mess, as they are a product of reality. Similary, fontinst is a mess, not necessarily by design, but because it has to cope with the mess we call reality. Contents I Overview of TEX font technology II Installation TEX fonts with fontinst III Overview of math fonts EuroT X ’99 Heidelberg 24. September 1999 3 E · · I Overview of TEX font technology What is a font? What is a virtual font? • Font file formats and conversion utilities • Font attributes and classifications • Font selection schemes • Font naming schemes • Font encodings • What’s in a standard font? What’s in an expert font? • Font installation considerations • Why the need for reencoding? • Which raw font encoding to use? • What’s needed to set up fonts for use with T X? • E EuroT X ’99 Heidelberg 24. September 1999 4 E · · What is a font? in technical terms: • – fonts have many different representations depending on the point of view – TEX typesetter: fonts metrics (TFM) and nothing else – DVI driver: virtual fonts (VF), bitmaps fonts(PK), outline fonts (PFA/PFB or TTF) – PostScript: Type 1 (outlines), Type 3 (anything), Type 42 fonts (embedded TTF) in general terms: • – fonts are collections of glyphs (characters, symbols) of a particular design – fonts are organized into families, series and individual shapes – glyphs may be accessed either by character code or by symbolic names – encoding of glyphs may be fixed or controllable by encoding vectors font information consists of: • – metric information (glyph metrics and global parameters) – some representation of glyph shapes (bitmaps or outlines) EuroT X ’99 Heidelberg 24. -

Vision Performance Institute

Vision Performance Institute Technical Report Individual character legibility James E. Sheedy, OD, PhD Yu-Chi Tai, PhD John Hayes, PhD The purpose of this study was to investigate the factors that influence the legibility of individual characters. Previous work in our lab [2], including the first study in this sequence, has studied the relative legibility of fonts with different anti- aliasing techniques or other presentation medias, such as paper. These studies have tested the relative legibility of a set of characters configured with the tested conditions. However the relative legibility of individual characters within the character set has not been studied. While many factors seem to affect the legibility of a character (e.g., character typeface, character size, image contrast, character rendering, the type of presentation media, the amount of text presented, viewing distance, etc.), it is not clear what makes a character more legible when presenting in one way than in another. In addition, the importance of those different factors to the legibility of one character may not be held when the same set of factors was presented in another character. Some characters may be more legible in one typeface and others more legible in another typeface. What are the character features that affect legibility? For example, some characters have wider openings (e.g., the opening of “c” in Calibri is wider than the character “c” in Helvetica); some letter g’s have double bowls while some have single (e.g., “g” in Batang vs. “g” in Verdana); some have longer ascenders or descenders (e.g., “b” in Constantia vs. -

A Collection of Mildly Interesting Facts About the Little Symbols We Communicate With

Ty p o g raph i c Factettes A collection of mildly interesting facts about the little symbols we communicate with. Helvetica The horizontal bars of a letter are almost always thinner than the vertical bars. Minion The font size is approximately the measurement from the lowest appearance of any letter to the highest. Most of the time. Seventy-two points equals one inch. Fridge256 point Cochin most of 50the point Zaphino time Letters with rounded bottoms don’t sit on the baseline, but slightly below it. Visually, they would appear too high if they rested on the same base as the squared letters. liceAdobe Caslon Bold UNITED KINGDOM UNITED STATES LOLITA LOLITA In Ancient Rome, scribes would abbreviate et (the latin word for and) into one letter. We still use that abbreviation, called the ampersand. The et is still very visible in some italic ampersands. The word ampersand comes from and-per-se-and. Strange. Adobe Garamond Regular Adobe Garamond Italic Trump Mediaval Italic Helvetica Light hat two letters ss w it cam gue e f can rom u . I Yo t h d. as n b ha e rt en ho a s ro n u e n t d it r fo w r s h a u n w ) d r e e m d a s n o r f e y t e t a e r b s , a b s u d t e d e e n m t i a ( n l d o b s o m a y r S e - d t w A i e t h h t t , h d e n a a s d r v e e p n t m a o f e e h m t e a k i i l . -

Download Futura Font Word

1 / 5 Download Futura Font Word Futuristic Fonts Download Free futuristic fonts at UrbanFonts.com Our site carries ... '80s generator gives your words a neon retro tribute Oct 07, 2016 · Well, if you ... Futuristic Logos Futura Fonts generator tool will let you convert simple and .... Download Futura fonts from UrbanFonts.com for PC and Mac. Futura EF Fonts Free ... Futura Lt Font. How to Install Futura Font in Adobe, Ms Word, Mac or Pc?. 11 Free Chrome Graphics Generators Welcome to MyFonts, the #1 place to download great @font-face webfonts and desktop fonts: classics (Baskerville, Futura, .... Mar 12, 2020 — Want to use beautiful custom fonts in your WordPress theme? ... First thing you need to do is download the font that you like in a web format.. Download Futura PT font (22 styles). Futura PT FuturaPTBold.otf 126 Kb | Futura PT Bold Italic FuturaPTBoldOblique.otf 125 Kb | Futura PT FuturaPTBook.otf ... Download Futura PT Font click here: https://windows10freeapps.com/futura-pt-font-free-download .... Free Font for Designers! High quality design resources for free. And helps introduce first time customers to your products with free fonts downloads and allow .... I'll use Futura PT Heavy which I downloaded from Adobe Typekit, but any font will work: ... This Font used for copy and paste and also for word generator.. Sep 23, 2011 — This is the page of Futura font. You can download it for free and without registration here. This entry was published on Friday, September 23rd .... ... the text it generates may look similar to text generated using the HTML or tags or the CSS attributes font-weight: bold or font-style: italic , it isn't. -

Gotische Schrift

l Gutenberg l Gotische Schrift l Schwabacher l Fraktur l Renaissance-Antiqua l Barock-Antiqua l Klassizistische Antiqua l Egyptienne l Grotesk l Jugendstil DIE ENTWICKLUNG DER DRUCKSCHRIFTEN l Johannes Gensfleisch, genannt Gutenberg * um 1400 in Mainz † 1468 ebenda Mit Gutenbergs Erfindung des Buchdrucks mit beweglichen Metalllettern und der Druckerpresse begann eine ganz neue Epoche. Die Verwendung der beweglichen Lettern ab 1450 revolutionierte die her- kömmliche Methode der Buchproduktion (Handschriften). Der Buchdruck breitete sich schnell in Europa und später in der ganzen Welt aus. Es begann die große Zeit der Entwicklung der Druckschriften. Im deutschsprachigen Raum setzten sich die gebrochenen Schrif- ten durch: Textura (Gotisch), Schwabacher, Fraktur und Kanzlei. Im italienischen Sprachraum konnte sich die gotische Schrift nicht durchsetzen. Dort entstand um 1300 die Rotunda oder Rundgotisch, eine offene Schrift von guter Lesbarkeit und Vorläufer der Antiqua-Schriften. GEBROCHENE SCHRIFTEN l Gotische Schrift (1300 – 1450) Von der Normandie breitete sich in Frank- reich ein neuer Stil aus: die Gotik. Dem Baustil entsprechend war auch die Schrift kantig und hochaufragend, das Schriftbild wirkte eng und düster. Damals bestimmte der christliche Glaube maßgebend das Leben und Kunstschaffen. Die Schrift der Zeit, die Textura, wurde ihrer würdevollen Form wegen hauptsäch- lich für liturgische Bücher verwendet. Auch Gutenberg schnitt seine Typen in dieser Schrift für seine Bibel. Daneben entwickelten sich die gotischen Buchkursiven mit ihren teilweise verschleif- ten Formen von großer Lebendigkeit. GEBROCHENE SCHRIFTEN l Schwabacher (1400) Im 15. Jhd. entstand durch die Vermi- schung der Textura mit der gotischen Kursivschrift die gut lesbare Schwabacher mit ihren offenen Formen. Der derbe Charakter brachte ihr gro- ße Beliebtheit und sie wurde bald zur meistgedruckten Schrift der volkstümlichen Literatur. -

Language and Materiality Ethnographic and Theoretical Explorations

Language and Materiality Ethnographic and Theoretical Explorations Edited by Jillian R. Cavanaugh CUNY, New York Shalini Shankar Northwestern University University Printing House, Cambridge CB2 8BS, United Kingdom One Liberty Plaza, 20th Floor, New York, NY 10006, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia 4843/24, 2nd Floor, Ansari Road, Daryaganj, Delhi - 110002, India 79 Anson Road, #06-04/06, Singapore 079906 Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge. It furthers the University’s mission by disseminating knowledge in the pursuit of education, learning, and research at the highest international levels of excellence. www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9781107180949 DOI: 10.1017/9781316848418 C Cambridge University Press 2017 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2017 Printed in <country> by <printer> A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data ISBN 978-1-107-18094-9 Hardback Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. 4 Fontroversy! Or, How to Care about the Shape of Language Keith M. Murphy Introduction On July 4, 2012, standing in the well of a packed lecture hall on the cam- pus of the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), just outside Geneva, particle physicist Joseph Incandela looked up at the hall’s projection screen and, with only a hint of nerves in his voice, uttered the following pro- nouncement: “If we combine the ZZ and gamma-gamma, this is what we get. -

Futura Is a Geometric Sans-Serif Typeface

M g o U & 9 n 1 G U 2 a O k s C N B Z T A G J % 6 G D 0 y 8 z E i u g 6 o U A n d l q G 7 @ 1 B Z f D S y m X Q e L Y V R u F N H O 9 I A H G P J k 4 0 g 8 j x H Y z K s u l c Q E 6 J 7 T L F t g q E j O & y R w b d s E 2 O A p i Y F V M a w 4 x N J L o R E m A h j s q W O Y % 3 l P i t 0 # H B C $ q s h D c a 4 J u g k o M A T 7 E G O 3 G m a Y F W 5 X I l u i c a b d G j D E A J h r o & q w n X D Y U P Classification: Futura is a geometric sans-serif typeface. It was a movement toward the modern Roman letter. It is widely used by contemporary designers for its crisp geometric and formal simplicity. Futura evokes a feeling of efficiency and moderness. Classification: Futura is a geometric sans-serif typeface. It was a movement toward the modern Roman letter. It is widely used by contemporary designers for its crisp geometric and formal simplicity. -

Futura Condensed Medium Hooligan Jf Steile Futura Bq

Bunker Living Style Guide BRANDMARK COLOUR PALETTE Primarily a monochromatic, dark grey colour variation is used on the spreads, reflecting of the printing practices mid twentieth century. A selection of dynamic, supporting colours are used sparingly on the cover pages and in an advertisement page inside the publication. #58595B 100% 75% 50% 25% 10% PRIMARY IMAGE TREATMENT Graphic imagery should evoke a vintage feel through the application of grit and texture. Illustrated elements with- in the publication are displayed an a grey-scale format. #A73C36 #183763 #90AAAC #374B28 #77854A SUPPORTING TEXTURE PALETTE Texture is used to illuminate and authenticate the worn and torn vintage magazine feel. TYPOGRAPHIC PALETTE A variety of mid-century, vintage type styles have been combined for a nostalgic effect. There is a varying degree of combinations and arrangement of styles. As a guide, the type used for headings and body copy differ with a good balance between serif and sans-serif options. SANS-SERIF SERIF SCRIPT BERNHARD GOTHIC URW BODONI 72 BOOK FUTURA CONDENSED MEDIUM CLARENDON URW REGULAR Fairwater Script Regular CRAW MODERN Fenway Park FUTURA MEDIUM FILMOTYPE LAKESIDE HELVETICA NEUE MEDIUM HELLENIC WIDE HOOLIGAN JF SUPERCLARENDON REGULAR VOLTA OPTIMA REGULAR POSTER GOTHIC ROUND STEILE FUTURA BQ publication spread dimension 210mm x 297mm Rationale Bunker Living adopts a unique position in the magazine market which is often inundated Influenced by iconic 1950s type pairing, hand-crafted illustration styles and grainy, worn- by generic, repetitive material that solely focuses one a single topic. This publication crafts in textures, the publication aligns suitably to the mid-century style. -

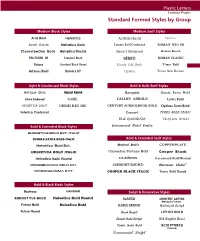

Standard Formed Styles by Group

Plastic Letters Formed Plastic Standard Formed Styles by Group Medium Block Styles Medium Serif Styles Arial Bold Helvetica Architectural Palatino Avant Garde Helvetica Italic Century Bold Condensed ROMAN NEO SB ClearviewOne Bold Helvetica Round Consort Condensed Roman Round FRUTIGER 65 Standard Block gemco ROMAN CLASSIC Futura Standard Block Round Goudy Old Style Times Bold Gil Sans Bold Univers 67 Optima Times New Roman Light & Condensed Block Styles Bold & Italic Serif Styles Antique Olive Impact Round Benguiat Goudy Extra Bold Futura Condensed KABEL CASLON ADBOLD Lotus Bold HELVETICA LIGHT standard block cond. CENTURY SCHOOLBOOK BOLD Optima Semi Bold Helvetica Condensed Consort TIMES BOLD ITALIC FRIZ QUADRATA TRAJAN BOLD Bold & Extended Block Styles Garamond Bold Italic EUROSTYLE BOLD EXT. ITALIC FUTURA EXTRA BOLD ITALIC Bold & Extended Serif Styles Helvetica Bold Ext. Bodoni Italic COPPERPLATE HELVETICA BOLD ITALIC Clarendon Fortune Bold Cooper Black Helvetica Italic Round clarion G a r a m ond B ol d R ou nd ® MICROGRAMMA BOLD EXT. CONSORT ROUND Herman Italic MICROGRAMMA EXT. COOPER BLACK ITALIC Times Bold Round Bold & Black Block Styles Bauhaus HARRIER Script & Decorative Styles EUROSTYLE BOLD Helvetica Bold Round BARNUM COUNTRY GOTHIC (Woodgrain Texture) Futura Bold Helvetica Bold CLASSIC BARNUM Italicized Script Futura Round Brush Script LITHOS BOLD Casual Italic Script Old English Bevel Comic Sans Bold SCULPTURED (Textured) Commercial Script Plastic Letters Formed Plastic MEDICAL SYMBOLS HEIGHT WIDTH DEPTH 12” 10” 1” 15 12 1 1/4 Staff of Asclepius Chiropractic Veterinary Symbol of Life 18 14 1 1/2 24 18 2 The Staff of Asclepius is the officially recognized medical DDS OD symbol of the American Medical Association. -

Modernizacijos Atspindžiai Lietuvos Taikomojoje Grafikoje. Art Deco Tipografika Ir Jos (Re)Aktualizacija

VILNIAUS DAILĖS AKADEMIJA GRAFINIO DIZAINO KATEDRA Magistro baigiamasis darbas Modernizacijos atspindžiai Lietuvos taikomojoje grafikoje. Art deco tipografika ir jos (re)aktualizacija Atliko: Jolanta Klišonytė . (parašas) Darbo vadovas: Prof. dr. Giedrė Jankevičiūtė . (parašas) Recenzentas: Dr. Gintarė Žemaitytė . (parašas) Vilnius 2015 Turinys Įvadas 1. Vakarų modernizmas ir tarpukario Lietuva 1.1.1 Lietuvos gyvenimo pokyčiai ir miesto kultūros raida 1.1.2 Art deco stilius ir jo apraiškos Lietuvoje 2. Tipografikos priemonių taikymas Lietuvos art deco taikomojoje grafikoje 2.1.1 Plakatai 2.1.2 Reklama 2.1.3 Knygų ir žurnalų viršeliai 2.2 Lietuvos tipografikos modernūs bruožai 3. Atvejo studija: Telesforo Kulakausko tipografika 4. Art deco tipografikos (re)aktualizacija Išvados Santrauka / Summary Priedai: A. M. Cassandre Nord Express 1927 plakato semiotinė analizė Literatūra Iliustracijos su pavadinimais 2 Aš, Jolanta Klišonytė, kandidatė grafinio dizaino magistro laipsniui gauti, pareiškiu, kad šis baigiamasis darbas paremtas mano paties tyrimais ir remiasi tik tokia papildoma informacija, kuri nurodyta nuorodose, paaiškinimuose, šaltinių, literatūros bei iliustracijų sąrašuose. Pareiškiu, kad baigiamajame darbe nėra naudojamasi kitų darbais to nenurodant ir nė viena baigiamojo darbo dalis nepažeidžia jokių asmens ar institucijos autorinių teisių. Taip pat nė viena baigiamojo darbo dalis nebuvo pateikta jokiai kitai aukštojo mokslo institucijai kaip akademinis atsiskaitymas ar siekiant gauti mokslo laipsnį. Vilnius, 2015 03 10 3 Įvadas Šią temą pasirinkau todėl, kad mane sudomino art deco stiliaus laikotarpyje pradėta naudoti tipografika ir jos ypatumai. Iki šiol tipografika, kaip XX a. Lietuvos modernizmo bruožas, nebuvo nagrinėta, ir tai mane paskatino labiau domėtis šia tema. Šis tyrimas yra glaudžiai susietas su praktiniu darbu, kuriame nagrinėju art deco modeliavimą šiuolaikiniame kontekste. -

„Bitstream“ Fonts

Key to the „Bitstream“ Fonts The history of typefaces is the history of forgeries. One of the greatest forgers of the 20th century was Matthew Carter. The Bitstream website (http://www.myfonts.com) describes him as follows: Matthew Carter of United Kingdom. Born: 1937 Son of Harry Carter, Royal Designer for Industry, contemporary British type designer and ultimate craftsman, trained as a punchcutter at Enschedé by Paul Rädisch, responsible for Crosfield's typographic program in the early 1960s, Mergenthaler Linotype's house designer 1965-1981. Carter co-founded Bitstream with Mike Parker in 1981. In 1991 he left Bitstream to form Carter & Cone with Cherie Cone. In 1997 he was awarded the TDC Medal, the award from the Type Directors Club presented to those „who have made significant contributions to the life, art, and craft of typography“. Carter’s „significant contribution to the life, art, and craft of typography“ consisted of forging the Linotype typeface collection. Carter can be characterized as a split personality. On the one hand, he has designed several original typefaces. On the other hand, he has forged hundreds of fonts. The following lists reveal that ca. 90% of the „Bitstream“ fonts are forgeries of the fonts contained in the catalog „LinoTypeCollection 1987“ („Mergenthaler Type Library“), i.e. the „Bitstream“ fonts are „nefarious evil knock-off clones“ (Bruno Steinert) of fonts sold by Linotype in the mid-1980s.1 „L“ in the following lists denotes that the font is contained in the „LinoTypeCollection 1987“. In the mid-1980s, the Linotype library comprised hundreds of typefaces with a total of 1700 fonts.