CS Rheintal.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schulen in Vorarlberg 9

Schulen in Vorarlberg 9. 1 10. 11. 12. 13. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. Polytechnische Bludenz, Bartholomäberg-Gantschier, Thüringen, Bregenz, Hittisau, Sozialberufe Bildungsanstalt für Elementarpädagogik (BAfEP) Schulen Bezau, Kleinwalsertal, Dornbirn, Feldkirch, Rankweil, Lauterach Feldkirch Voraussetzung: Kolleg für Elementarpädagogik BB BB BB AHS – Oberstufen Gymnasium Feldkirch Matura, BRP, SBP Bludenz, Bregenz (4x), Dornbirn (2x), Feldkirch, Lustenau Langformen Voraussetzung : Kolleg Dual für Elementarpädagogik Matura, BRP, SBP, BB BB BB BB Berufserfahrung Realgymnasium Feldkirch Bludenz, Bregenz, Dornbirn (2x), Feldkirch (2x) Fachschule für Pflege und Gesundheit Feldkirch AHS – Oberstufen ORG Schwerpunkt: Instrumentalunterricht Oberstufen- Dornbirn, Egg, Feldkirch, Götzis, Lauterach Technische Fachschule Maschinenbau - Fertigungstechnik + realgymnasium Schulen Werkzeug- und Vorrichtungsbau (ORG) ORG Schwerpunkt: Bildn. Gestalten + Werkerziehung HTL Maschinenbau Dornbirn, Egg, Feldkirch, Götzis, Lauterach HTL Bregenz HTL Automatisierungstechnik Smart Factory ORG Schwerpunkt: Naturwissenschaft Egg, Feldkirch, Götzis, Lauterach HTL Kunststofftechnik Product + Process Engineering ORG Bewegung & Gesundheit Bludenz HTL Elektrotechnik Smart Power + Motion ORG Wirtschaft & Digitales Voraus s etzung: Matura, B R P, SBP od. einschl. Fachschule od. Bludenz Kolleg/Aufbaulehrgang Maschinenbau Lehre u. Vorbereitungslg. oder Sportgymnasium, Dornbirn Technische Fachschule für Chemie Schulen Musikgymnasium, Feldkirch HTL Dornbirn Fachschule für Informationstechnik -

Spielplan Vorarlbergliga Saison 2019/2020

Spielplan Vorarlbergliga Saison 2019/2020 Runde Datum Heimverein Gastverein 1. Runde Sa., 27.07.2019 FC Nenzing VfB Bezau 1. Runde Sa., 27.07.2019 FC Schruns FC Hard 1. Runde Sa., 27.07.2019 FC Egg FC BW Feldkirch 1. Runde Sa., 27.07.2019 FC Alberschwende SC Göfis 1. Runde Sa., 27.07.2019 FC Andelsbuch SV Ludesch 1. Runde Sa., 27.07.2019 FC Lustenau SC Admira Dornbirn 1. Runde Sa., 27.07.2019 SV Lochau SC Fussach 1. Runde Sa., 27.07.2019 FC Bizau FC Höchst 2. Runde Sa., 03.08.2019 SC Fussach FC Lustenau 2. Runde Sa., 03.08.2019 SC Admira Dornbirn FC Andelsbuch 2. Runde Sa., 03.08.2019 SV Ludesch FC Alberschwende 2. Runde Sa., 03.08.2019 SC Göfis FC Egg 2. Runde Sa., 03.08.2019 FC BW Feldkirch FC Schruns 2. Runde Sa., 03.08.2019 FC Hard FC Bizau 2. Runde Sa., 03.08.2019 FC Höchst FC Nenzing 2. Runde Sa., 03.08.2019 VfB Bezau SV Lochau 3. Runde Sa., 10.08.2019 FC Nenzing SV Lochau 3. Runde Sa., 10.08.2019 FC Schruns SC Göfis 3. Runde Sa., 10.08.2019 FC Egg SV Ludesch 3. Runde Sa., 10.08.2019 FC Alberschwende SC Admira Dornbirn 3. Runde Sa., 10.08.2019 FC Andelsbuch SC Fussach 3. Runde Sa., 10.08.2019 FC Lustenau VfB Bezau 3. Runde Sa., 10.08.2019 FC Höchst FC Hard 3. Runde Sa., 10.08.2019 FC Bizau FC BW Feldkirch 4. Runde Mi., 14.08.2019 SC Fussach FC Alberschwende 4. -

Die Welt Beginnt Im Kleinen Engagiere Dich Mit Uns!

die welt beginnt im kleinen engagiere dich mit uns! FÖRDERN ENGAGEMENT AKTION B(r)OTSCHAFTEN VERTEILEN B(r)OTSCHAFTEN WIR BIN ICH Bürgerschaftliches Engagement ist Es soll bewusst gemacht werden, dass das tägliche Brot einer gesunden Ge- jeder Einzelne wichtig ist und etwas be- sellschaft. Das Wortspiel „WIR bin ICH“ wegen kann. bringt tiefgründig zum Ausdruck, wie wichtig das Füreinander in der Gesell- Die B(r)OTSCHAFTEN verschaffen schaft ist. uns die Möglichkeit, diese Inhalte und Gedanken einer größeren Zielgruppe In einer gemeinsamen Initiative von (mehr als 80.000 Brotsäcke) näher zu acht Bäckereien des Bregenzerwalds bringen. So wird ein Anstoß zur persön- und des Leiblachtals werden die Papier- lichen Weiterentwicklung gegeben und säcke, in denen das tägliche Brot über die Saat für mögliche Aktivitäten für den Ladentisch wandert, mit verschie- das Gemeinwohl gelegt. denen B(r)OTSCHAFTEN bedruckt. Diese zeigen auf, wie wichtig und nötig Rolle „Engagiert sein“ das „sich einbringen“ jedes Einzelnen Die Freiwilligenkoordinatorinnen ha- in unsere Gesellschaft ist. Gleichzeitig ben die Aktion mit den acht Bäckereien ist durchaus beabsichtigt, dass die Brot- initiiert und begleitet. Bezugnehmend käuferInnen die eigene persönliche auf die B(r)OTSCHAFTEN Aktion und Haltung und Einstellung kritisch hin- dem transportierten Slogan „WIR bin terfragen. ICH“ werden im Herbst 2018 über das Projekt „Engagiert sein“ verschiedene Es gibt 100 große und kleine Dinge die Veranstaltungen zu diesem Thema ICH jeden Tag für ein besseres WIR tun stattfinden. kann. TU ES! [email protected] www.engagiert-sein.at SCHAFFEN WORTORTE KINDERBÜCHERKÄSTEN Bilder: Ariane Grimm Ariane Bilder: UNTERSTÜTZEN DAS LESEN WORTORTE IM BREGENZERWALD Die bunten Würfel sind kleine Bibliotheken im öffentlichen Raum, voll mit aussortierten Büchern für Kinder bis zehn Jahre. -

MONTFORT Zeitschrift Für Geschichte Vorarlbergs

65. Jahrgang 2013 BAND 1 MONTFORT Zeitschrift für Geschichte Vorarlbergs Walserspuren – 700 Jahre Walser in Vorarlberg Innsbruck Wien StudienVerlag Bozen Impressum Gefördert vom Land Vorarlberg Schriftleitung: ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Alois Niederstätter, Vorarlberger Landesarchiv, Kirchstraße 28, A-6900 Bregenz, Tel.: +43 (0)5574 511 45005, Fax: + 43 (0)5574 511 45095; E-Mail: [email protected] © 2013 by StudienVerlag Layout und Satz: Karin Berner/StudienVerlag Verlag: StudienVerlag, Erlerstraße 10, A-6020 Innsbruck; Tel.: +43 (0)512 395045, Fax: +43 (0)512 395045-15; E-Mail: [email protected]; Internet: http://www.studienverlag.at Bezugsbedingungen: Montfort erscheint zweimal jährlich. Einzelheft € 21.00/sfr 28.90, Jahresabonnement € 36.50/sfr 46.50 (inkl. 10 % MwSt., zuzügl. Versand). Alle Bezugspreise und Versandkosten unterliegen der Preisbindung. Abbestellungen müssen spätestens drei Monate vor Ende des Kalenderjahres schriftlich erfolgen. Abonnement-Bestellungen richten Sie bitte an den Verlag, redaktionelle Zuschriften (Artikel, Besprechungsexemplare) an die Schriftleitung. Für den Inhalt der einzelnen Beiträge sind ausschließlich die Autorinnen und Autoren verantwortlich. Für unverlangt eingesandte Manuskripte übernehmen Schriftleitung und Verlag keine Haftung. Die Zeitschrift und alle in ihr enthaltenen Beiträge sind urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlags unzulässig. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, -

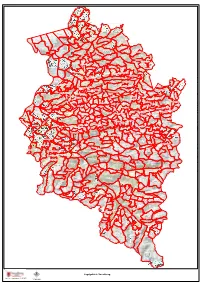

Jagdgebiete.Pdf (4.9

GJ Hohenweiler GJ Möggers GJ Hörbranz il e T r e r e t n u - g r e b l n i e e T h c r i e E r e J b G o - GJ Langen III g E r J e b B n EJ Hirschberg/Bregenz o e GJ Sulzberg II d h e c n i E s e GJ Lochau J e G GJ Sulzberg I -B r e EJ Bodensee-Rieden g e n z GJ Langen I GJ Langen II GJ Riefensberg GJ Höchst (See) GJ Doren II EJ Bregenz GJ Rieden GJ Hard GJ Fluh G GJ Fussach J G a i ß GJ Doren I a G u J Ke GJ Krumbach nne GJ Buch I lbac I h e d n GJ Höchst (Land) e GJ Bolgenach I w h c s r e b GJ Buch l GJ Bolgenach III A GJ Lauterach GJ Wolfurt J GJ Langenegg/Bregenz GJ Bolgenach II G EJ Koppach-Ochsenlager GJ Al ber GJ Bildstein sch we nd e I -No E rd J GJ Hittisau II A u G GJ Hittisau I er -R J GJ Lingenau ie A GJ Alberschwende I-Süd d l b e GJ Schwarzach r s c h w EJ Galtburst e EJ Wolfurter-Vorderries n d e I G GJ Winsau I EJ Gmeiners Burst I J GJ Egg II S ib GJ Egg IV ra t GJ Dornbirn - Fallenberg s r I g g e er f GJ Dornbirn - Ried-Nord nb ä t ze G t ar ll GJ Sibratsgfäll-Ost EJ Bödele-Oberlose w J - ä Sch S W t J c s G h e w s r a e E rz t u J en e b B e r F GJ Lustenau g ö II GJ Egg V GJ Egg I J d G e l e GJ Schwarzenberg III EJ Althauserwies - O V b rg GJ Egg III GJ e be Sib r n r at l e sg o f rz äll-S s a ü G V w d e I ch J g S r J n D e e b G l o n r e h n GJ Dornbirn - Schwende z ü b r G GJ Andelsbuch III J EJ Hinterbrongen-Triesten B i a A - r n z EJ Krähenberg n w d l h e EJ Finne-Gunten - c ls a b f R S uc r i J h e e G II t d n - U S GJ Andelsbuch I ü J EJ Oster-Ödgunten d E E J EJ Rothenbach GJ Staufen-Haslach GJ Kehlegg -

Elternbildungs- Einrichtungen

Ermässigung von 30 Prozent: Elternbildungs- Bildungshaus Batschuns Zwischenwasser, T +43 5522 44290 0, www.bildungshaus-batschuns.at einrichtungen „Familiengespräche" Vorarlberger Familienverband Vergünstigte Angebote: Bregenz, T +43 5574 47671, www.familie.or.at Jugend- und Bildungshaus St. Arbogast Erfahrungen mit anderen Eltern austau- „Gigagampfa" Götzis, T +43 5523 625010, schen, praktische Anregungen für den Ehe- und Familienzentrum www.arbogast.at Erziehungsalltag mitnehmen, eigene Stärken der Diözese Feldkirch entdecken, eine Auszeit vom Alltag Feldkirch, T +43 5522 74139, Katholische ArbeitnehmerInnen- nehmen und das Zusammensein mit Kindern www.efz.at Bewegung Vorarlberg in entspannter Atmosphäre erleben – das ist Götzis, T +43 664 2146651, das Ziel von Weiterbildungs an geboten. „Kinder brauchen Antworten“ www.kab-vorarlberg.com IfS – Institut für Sozialdienste Röthis, T +43 5 1755530, Katholisches Bildungswerk Vorarlberg Eltern und Erziehungs berechtigte www.ifs.at Feldkirch, T +43 664 2146651, erhalten mit dem Vorarlberger www.elternschule-vorarlberg.at Familienpass bei allen vom Land „Wertvolle Kinder“ & „Familienimpulse" geförderten Veranstaltungen eine Vorarlberger Kinderdorf Volkshochschule Bludenz Ermäßigung. Bregenz, T +43 5574 49920, Bludenz, T +43 5552 65205, www.vorarlberger-kinderdorf.at www.vhs-bludenz.at „Eltern-chat“ & „Purzelbaum-Eltern- Volkshochschule Bregenz Weitere Informationen unter: Kind-Gruppen“ Bregenz, T +43 5574 525240, www.vorarlberg.at/familie (Elternbildung) Katholisches Bildungswerk Vorarlberg www.vhs-bregenz.at und www.pffiffikus.at Feldkirch, T +43 5522 34850, www.elternschule-vorarlberg.at Volkshochschule Rankweil Rankweil, T +43 5522 46562, www.schlosserhus.at weitere Anbietende Bodenseeakademie okay.zusammen leben – Projektstelle Vorarlberger Kinderfreunde Dornbirn, T +43 5572 33064, für Zuwanderung und Integration Bregenz, T +43 664 9120446, www.bodenseeakademie.at Dornbirn, T +43 5572 3981020, www.kinderfreunde.at www.okay-line.at connexia – Gesellschaft für Gesundheit Volkshochschule Götzis und Pflege gem. -

Silvesterlauf 2007 Bestzeitliste Total

Bestzeitliste Total Silvesterlauf 2007 Hochlitten/Riefensberg, 31.12.2007 Rg Stn Name + Vorname JG Verein Laufzeit Differenz 1 130 HAGER Bernhard 1969 WSV Schoppernau 43.01 2 123 DIETRICH Claudio 1977 SV Mellau 43.69 0.68 3 144 GRAF Bernhard 1988 ÖSV 43.76 0.75 4 106 HIRSCHBÜHL Pepi 1961 SV Riefensberg 44.19 1.18 5 145 GMEINER Michael 1985 ÖSV 44.20 1.19 6 128 MUXEL Martin 1973 SV Reuthe 44.74 1.73 7 16 GRAF Mathias 1996 SC Rheintal 44.98 1.97 8 151 MOOSBRUGGER Silvio 1988 SV Mellau 45.48 2.47 9 175 RÄDLER Riccardo 1992 SC Möggers 45.51 2.50 10 173 SINZ Mathias 1983 SV Doren 45.55 2.54 11 155 GEIGER Wolfgang 1978 SV Riefensberg 45.59 2.58 12 85 WIRTH Katja 1980 ÖSV 45.75 2.74 13 125 ZAUSER Thomas 1976 SV Bizau 45.96 2.95 13 69 MEUSBURGER Patrick 1994 SV Mellau 45.96 2.95 15 162 EBERLE Georg 1990 WSV Sibratsgfäll 45.97 2.96 16 152 GASSNER Philipp 1992 SV Neuenbürg (D) 45.99 2.98 17 157 ZAUSER Christoph 1978 SV Dornbirn 46.01 3.00 18 111 ZÜNDEL Günter 1966 SV Mellau 46.15 3.14 19 174 FINK Richard 1979 SV Sulzberg 46.17 3.16 20 163 MEUSBURGER Michael 1992 SV Höchst 46.22 3.21 21 161 MANGARD Stefan 1980 WSV St. Gallenkirch 46.36 3.35 22 129 MÜLLER Hubert 1971 SV Buch 46.39 3.38 23 164 EBERLE Richard 1981 WSV Sibratsgfäll 46.44 3.43 24 63 KIEßLING Marcus 1993 TSV Stiefenhofen 46.49 3.48 25 8 HEIM Julia 1995 SC Bezau 46.59 3.58 26 139 LINDER Thomas 1973 SC Rheintal 46.62 3.61 26 117 WINDER Reinhard 1962 SV Bildstein 46.62 3.61 28 176 SPETTEL Mario 1990 SC Alberschwende 46.79 3.78 29 169 EBERLE Walter 1982 SCU Hittisau 46.88 3.87 30 136 MOOSBRUGGER -

GIS-Based Roughness Derivation for Flood Simulations: a Comparison of Orthophotos, Lidar and Crowdsourced Geodata

Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 1739-1759; doi:10.3390/rs6021739 OPEN ACCESS remote sensing ISSN 2072-4292 www.mdpi.com/journal/remotesensing Article GIS-Based Roughness Derivation for Flood Simulations: A Comparison of Orthophotos, LiDAR and Crowdsourced Geodata Helen Dorn 1, Michael Vetter 2,3 and Bernhard Höfle 1,* 1 Institute of Geography & Heidelberg Center for the Environment (HCE), Heidelberg University, Berliner Str. 48, D-69120 Heidelberg, Germany; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Institute of Geography, University of Innsbruck, Innrain 52f, A-6020 Innsbruck, Austria; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Centre for Water Resource Systems; Research Groups Photogrammetry & Remote Sensing, Vienna University of Technology, Karlsplatz 13, A-1040 Vienna, Austria * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-6221-54-5594; Fax: +49-6221-54-4529. Received: 4 October 2013; in revised form: 28 January 2014 / Accepted: 12 February 2014 / Published: 24 February 2014 Abstract: Natural disasters like floods are a worldwide phenomenon and a serious threat to mankind. Flood simulations are applications of disaster control, which are used for the development of appropriate flood protection. Adequate simulations require not only the geometry but also the roughness of the Earth’s surface, as well as the roughness of the objects hereon. Usually, the floodplain roughness is based on land use/land cover maps derived from orthophotos. This study analyses the applicability of roughness map derivation approaches for flood simulations based on different datasets: orthophotos, LiDAR data, official land use data, OpenStreetMap data and CORINE Land Cover data. -

Lag Vorderland Walgau Bludenz

LAG VORDERLAND WALGAU BLUDENZ Lokale Entwicklungsstrategie 2014 – 2020 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Beschreibung der Lokalen Aktionsgruppe 5 1.1 Festlegung des Gebiets und Beschreibung der Gebietscharakteristik 5 1.2 Angaben zur Bevölkerungsstruktur 6 2. Analyse des Entwicklungsbedarfs 7 2.1 Beschreibung der Region und der sozioökonomischen Lage 7 2.2 Reflexion und Erkenntnisse aus der Umsetzung von LEADER in der Periode 2007 – 2013 9 2.3 SWOT-Analyse der Region 9 2.4 Darstellung der lokalen Entwicklungsbedarfe 14 3. Lokale Entwicklungsstrategie 17 3.1 Aktionsfeld 1: Wertschöpfung 19 3.2 Aktionsfeld 2: Natürliche Ressourcen und kulturelles Erbe 31 3.3 Aktionsfeld 3: Gemeinwohl Strukturen und Funktionen 39 3.4 Aktionsfeld IWB 54 3.5 Aktionsfeld ETZ 54 3.6 Berücksichtigung der Ziele der Partnerschaftsvereinbarung und des Programms LE 2020 und falls zutreffend der IWB und ETZ-Programme 55 3.7 Berücksichtigung der bundeslandrelevanten und regionsspezifischen Strategien 57 3.8 Erläuterung der integrierten, multisektoralen und innovativen Merkmale der Strategie 57 3.9 Beschreibung geplanter Zusammenarbeit und Vernetzung 58 4. Steuerung und Qualitätssicherung 60 4.1 Beschreibung der Vorkehrungen für Steuerung, Monitoring und Evaluierung der LAG-internen Umsetzungsstrukturen 60 4.2 Beschreibung der Vorkehrungen für Steuerung, Monitoring und Evaluierung der Strategie- und Projektumsetzung inkl. Reporting an die Verwaltungsbehörde und Zahlstelle 61 5. Organisationsstruktur der LAG 62 5.1 Rechtsform der LAG 62 5.2 Zusammensetzung der LAG (inklusive Darlegung der Struktur und getroffenen Vorkehrungen, die gewährleisten, dass die Bestimmungen des Art. 32 der Verordnung (EU) Nr. 1303/2013 permanent eingehalten werden) 62 5.3 LAG-Management 63 5.4 Projektauswahlgremium (inklusive Geschäftsordnung, die gewährleistet, dass die Bestimmungen des Art. -

Landratsamt Bregenz 1940-1945

Vorarlberger Landesarchiv 1/60 Rep. 14-300 Landratsamt Bregenz 1940-1945 Landratsamt Bregenz 1940-1945 1. Bestandsgeschichte Die Akten des Landratsamtes (LRA) Bregenz wurden durch die Bezirkshauptmannschaft (BH) Bregenz zu einem bei der Abfassung dieser Bestandsübersicht, d. i. das Jahr 2002, nicht mehr eruierbaren Zeitpunkt an das Vorarlberger Landesarchiv übergeben. Die Akten waren in Faszikeldeckel verpackt, provisorisch beschriftet und wurden im Keller des Hauptgebäudes des Vorarlberger Landesarchivs (VLA) in der Kirchstraße 28 in Bregenz gelagert. Die klima- tischen Bedingungen in diesem Keller zeichneten sich durch eine hohe Luftfeuchtigkeit (im Jahresschnitt 65 %) und jahreszeitlich bedingte schwankende Temperaturen aus. Der gesamte Bestand wurde von Mai bis November 2002 durch Mitarbeiter des Verwaltungsarchivs im VLA, Herrn Robert Demarki und Dr. Wolfgang Weber, neu bewertet und erschlossen. Im Zuge dieser Arbeiten wurde das Schriftgut der Jahrgänge 1940-1945 des LRA Bregenz von Metallklammern gesäubert, lose Aktenkonvolute in säurefreie Umschläge eingelegt, in säure- freie Schachteln umgebettet und diese neu beschriftet. Das Aktenmaterial ist gleichzeitig einer genauen Prüfung auf Pilz- und Schimmelbefall unterzogen und ggf. skartiert worden. Als Grundlage für die Ablage und Neuverzeichnung der Akten des LRA Bregenz diente der überlieferte Einheitsaktenplan des LRA Bregenz aus dem Jahr 1942, der im Repertorienzim- mer des VLA zugänglich ist. Für die Bau- und Gewerbeakten sind eigene Findbücher überlie- fert, auf die in dieser Auflistung bei den einschlägigen Akten hingewiesen wird. Sie sind ebenfalls im Repertorienzimmer zugänglich. Nicht alle im Aktenplan 1942 verzeichneten Akten waren tatsächlich überliefert, die fehlen- den bzw. nicht überlieferten Akten wurden im Einheitsaktenplan mit einem roten Stempel „SKARTIERT“ ausgewiesen. Als Datum der Vernichtung gilt der 18.11.2002, auch wenn zahlreiche Akten offenbar schon durch die Behörde vernichtet (sic!) und nie an das VLA ab- gegeben wurden. -

Fahrplan Für Linie 73-1

Ausdruck vom 07.11.2005 Fahrplansaison: Blumenegger 05/06 73 Bludenz - Schlins - Satteins - Feldkirch Montag - Freitag Bludenz Riedmillerplatz 6:58 Bludenz Postamt 5:32 6:32 I 7:32 Bludenz Bahnhof 5:35 6:35 7:02 7:35 Bludenz Alte Landstraße 5:37 I 7:04 I Bludenz Hotel Einhorn 5:38 I 7:05 I Nüziders Lindenweg 5:39 I 7:06 I Nüziders Kapelle 5:40 I 7:07 I Bludenz Am Tobel I 6:37 I 7:37 Nüziders Bürser Brücke I 6:38 I 7:38 Nüziders Hubertus I 6:39 I 7:39 Nüziders Feuerwehrhaus I 6:41 I I Nüziders Postamt 5:42 6:42 7:09 I Nüziders Bahnhaltestelle 5:44 6:44 7:11 7:41 Nüziders Rämpele 5:45 6:45 7:12 7:42 Ludesch Gärtnerei Metzler 5:46 I 7:13 7:43 Ludesch Unterfeld I 6:46 I I Ludesch Bahnhof I 6:48 I I Ludesch Sutterlüty 5:47 6:50 7:14 7:44 Ludesch Beim Kreuz 5:48 6:51 7:15 7:45 Ludesch Gemeindeamt 5:49 6:52 7:16 7:46 Ludesch Brärsch 5:51 6:54 7:18 7:48 Thüringen Elektro Brugger 5:52 I I I Thüringen Sportplatz I 6:57 7:21 7:51 Thüringen Hauptschule I 6:58 7:22 7:52 L77 von Damüls Sommersaison an 7:10 7:50 L78 von Marul / Seilbahn Stein Sommersaison an 7:52 L 77 von Damüls Wintersaison an 7:10 7:50 L78 von Sonntag Stein / Marul Wintersaison an 7:52 Thüringen Gemeindeamt 5:53 6:59 7:23 7:53 L77 nach Damüls Sommersaison ab 7:08 8:08 L78 nach Marul / Seilbahn Stein Sommersaison ab 8:06 L77 nach Damüls Wintersaison ab 7:08 8:08 L 78 nach Marul / Sonntag Stein Wintersaison ab Thüringen J.-Douglas-Str. -

Media Information

Media Information Winter 2019/20 Information & Service The contents of this compilation were collected in June and July 2019 and any changes made known to us have been integrated since then. The contents are based on our own research and information provided by the partners. Press text online You can download the entire text online at www.bregenzerwald.at/en/media Photos online You can find a selection of matching photos – to be used in a touristic context and only in conjunction with a report about the Bregenzerwald – at www.bregenzerwald.at/en/media Bregenzerwald Tourismus - Social Media www.instagram.com/visitbregenzerwald | #visitbregenzerwald | @visitbregenzerwald www.facebook.com/visitbregenzerwald www.youtube.com/bregenzerwaldtourism Available brochures ▪ The Bregenzerwald Travel Magazine (German only) appears twice a year – once in the summer and once in the winter – with around 60 pages of edited stories and reports. Regional and international authors report on people in and from the Bregenzerwald and about those things which give them pleasure and joy. The Bregenzerwald Travel Magazine is available online at www.bregenzerwald.at. The website is also home to some of the magazine stories in English. ▪ The Bregenzerwald Travel Guide is published at the same time as the Travel Magazine every six months (winter and summer). The winter edition contains useful information about skiing areas, ski passes, ski schools and winter sporting activities – from cross-country skiing through to winter hikes, culture, architecture, culinary delights and wellness offers. Research trips Would you like to see the Bregenzerwald for yourself? Please feel free to contact Mag. Cornelia Kriegner. Contact for media enquiries Bregenzerwald Tourismus Mag.