Get the Classic #5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Heather Marlene Bennett University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Bennett, Heather Marlene, "Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 734. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Abstract The traumatic legacies of the Paris Commune and its harsh suppression in 1871 had a significant impact on the identities and voter outreach efforts of each of the chief political blocs of the 1870s. The political and cultural developments of this phenomenal decade, which is frequently mislabeled as calm and stable, established the Republic's longevity and set its character. Yet the Commune's legacies have never been comprehensively examined in a way that synthesizes their political and cultural effects. This dissertation offers a compelling perspective of the 1870s through qualitative and quantitative analyses of the influence of these legacies, using sources as diverse as parliamentary debates, visual media, and scribbled sedition on city walls, to explicate the decade's most important political and cultural moments, their origins, and their impact. -

Revolution at a Standstill: Photography and the Paris Commune of 1871 Author(S): Jeannene M

Revolution at a Standstill: Photography and the Paris Commune of 1871 Author(s): Jeannene M. Przyblyski Source: Yale French Studies, No. 101, Fragments of Revolution (2001), pp. 54-78 Published by: Yale University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3090606 Accessed: 02-04-2018 16:28 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Yale University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Yale French Studies This content downloaded from 136.152.208.140 on Mon, 02 Apr 2018 16:28:15 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms JEANNENE M. PRZYBLYSKI Revolution at a Standstill: Photography and the Paris Commune of 1871* Revolution is a drama perhaps more than a history, and its pathos is a condition as imperious as its authenticity. -Auguste Blanqui "Angelus Novus'1 Look at them. Heads peering over piles of paving stones, smiling for the camera or squinting down the barrel of a gun (Fig. 1). They stand bathed in the flat light of late winter, suspended between the fact of photographic stillness and the promise of fighting in the streets. It hardly needs saying that in March of 1871 Paris itself was no less be- tween states-half taken apart, half put back together. -

Romantik 08 2019

Journal for the Study of Romanticisms (2019), Volume 08, DOI 10.14220/jsor.2019.8.issue-1 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen Journal for the Study of Romanticisms (2019), Volume 08, DOI 10.14220/jsor.2019.8.issue-1 Romantik Journal for the Study of Romanticisms Editors Cian Duffy(Lund University), Karina Lykke Grand (Aarhus University), Thor J. Mednick (University of Toledo), Lis Møller (Aarhus University), ElisabethOx- feldt (UniversityofOslo), Ilona Pikkanen (Tampere University and the Finnish Literature Society), Robert W. Rix (University of Copenhagen), and AnnaLena Sandberg (University of Copenhagen) Advisory Board Charles Armstrong (UniversityofBergen), Jacob Bøggild (University of Southern Denmark, Odense), David Fairer (University of Leeds), Karin Hoff (Georg-August-Universität Göttingen),Stephan Michael Schröder (University of Cologne), David Jackson (University of Leeds),Christoph Bode (LMU München), CarmenCasaliggi (Cardiff Metropolitan University), Gunilla Hermansson (University of Gothernburg), Knut Ljøgodt (Nordic Institute of Art, Oslo), and Paula Henrikson (Uppsala University) Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen Journal for the Study of Romanticisms (2019), Volume 08, DOI 10.14220/jsor.2019.8.issue-1 Romantik Journal for the Study of Romanticisms Volume 08|2019 V&Runipress Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen Journal for the Study of Romanticisms (2019), Volume 08, DOI 10.14220/jsor.2019.8.issue-1 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. -

PROCEEDINGS of the 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION of the VETERANS of FOREIGN WARS of the UNITED STATES

116th Congress, 2d Session House Document 116–165 PROCEEDINGS of the 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES (SUMMARY OF MINUTES) Orlando, Florida ::: July 20 – 24, 2019 116th Congress, 2d Session – – – – – – – – – – – – – House Document 116–165 THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 120TH NATIONAL CON- VENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES COMMUNICATION FROM THE ADJUTANT GENERAL, THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES, HELD IN ORLANDO, FLORIDA: JULY 20–24, 2019, PURSUANT TO 44 U.S.C. 1332; (PUBLIC LAW 90–620 (AS AMENDED BY PUBLIC LAW 105–225, SEC. 3); (112 STAT. 1498) NOVEMBER 12, 2020.—Referred to the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 40–535 WASHINGTON : 2020 U.S. CODE, TITLE 44, SECTION 1332 NATIONAL ENCAMPMENTS OF VETERANS’ ORGANIZATIONS; PROCEEDINGS PRINTED ANNUALLY FOR CONGRESS The proceedings of the national encampments of the United Spanish War Veterans, the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, the American Legion, the Military Order of the Purple Heart, the Veterans of World War I of the United States, Incorporated, the Disabled American Veterans, and the AMVETS (American Veterans of World War II), respectively, shall be printed annually, with accompanying illustrations, as separate House documents of the session of the Congress to which they may be submitted. [Approved October 2, 1968.] ii LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI September, 2020 Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Speaker U. -

Valeska Soares B

National Museum of Women in the Arts Selections from the Collection Large-Print Object Labels As of 8/11/2020 1 Table of Contents Instructions…………………………………………………..3 Rotunda……………………………………………………….4 Long Gallery………………………………………………….5 Great Hall………………….……………………………..….18 Mezzanine and Kasser Board Room…………………...21 Third Floor…………………………………………………..38 2 National Museum of Women in the Arts Selections from the Collection Large-Print Object Labels The large-print guide is ordered presuming you enter the third floor from the passenger elevators and move clockwise around each gallery, unless otherwise noted. 3 Rotunda Loryn Brazier b. 1941 Portrait of Wilhelmina Cole Holladay, 2006 Oil on canvas Gift of the artist 4 Long Gallery Return to Nature Judith Vejvoda b. 1952, Boston; d. 2015, Dixon, New Mexico Garnish Island, Ireland, 2000 Toned silver print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Susan Fisher Sterling Top: Ruth Bernhard b. 1905, Berlin; d. 2006, San Francisco Apple Tree, 1973 Gelatin silver print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Gift of Sharon Keim) 5 Bottom: Ruth Orkin b. 1921, Boston; d. 1985, New York City Untitled, ca. 1950 Gelatin silver print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Joel Meyerowitz Mwangi Hutter Ingrid Mwangi, b. 1975, Nairobi; Robert Hutter, b. 1964, Ludwigshafen am Rhein, Germany For the Last Tree, 2012 Chromogenic print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Tony Podesta Collection Ecological concerns are a frequent theme in the work of artist duo Mwangi Hutter. Having merged names to identify as a single artist, the duo often explores unification 6 of contrasts in their work. -

George Eastman Museum Annual Report 2016

George Eastman Museum Annual Report 2016 Contents Exhibitions 2 Traveling Exhibitions 3 Film Series at the Dryden Theatre 4 Programs & Events 5 Online 7 Education 8 The L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation 8 Photographic Preservation & Collections Management 9 Photography Workshops 10 Loans 11 Objects Loaned for Exhibitions 11 Film Screenings 15 Acquisitions 17 Gifts to the Collections 17 Photography 17 Moving Image 22 Technology 23 George Eastman Legacy 24 Purchases for the Collections 29 Photography 29 Technology 30 Conservation & Preservation 31 Conservation 31 Photography 31 Moving Image 36 Technology 36 George Eastman Legacy 36 Richard & Ronay Menschel Library 36 Preservation 37 Moving Image 37 Financial 38 Treasurer’s Report 38 Fundraising 40 Members 40 Corporate Members 43 Matching Gift Companies 43 Annual Campaign 43 Designated Giving 45 Honor & Memorial Gifts 46 Planned Giving 46 Trustees, Advisors & Staff 47 Board of Trustees 47 George Eastman Museum Staff 48 George Eastman Museum, 900 East Avenue, Rochester, NY 14607 Exhibitions Exhibitions on view in the museum’s galleries during 2016. Alvin Langdon Coburn Sight Reading: ONGOING Curated by Pamela G. Roberts and organized for Photography and the Legible World From the Camera Obscura to the the George Eastman Museum by Lisa Hostetler, Curated by Lisa Hostetler, Curator in Charge, Revolutionary Kodak Curator in Charge, Department of Photography Department of Photography, and Joel Smith, Curated by Todd Gustavson, Curator, Technology Main Galleries Richard L. Menschel -

Aesthetics in Ruins: Parisian Writing, Photography and Art, 1851-1892

Aesthetics in Ruins: Parisian Writing, Photography and Art, 1851-1892 Ioana Alexandra Tranca Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Trinity College March 2017 I would like to dedicate this thesis to my parents, Mihaela and Alexandru Declaration I hereby declare that this dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. This dissertation does not exceed the prescribed word limit of 80000, excluding bibliography. Alexandra Tranca March 2017 Acknowledgements My heartfelt gratitude goes to my Supervisor, Dr Nicholas White, for his continued advice and support throughout my academic journey, for guiding and helping me find my way in this project. I also wish to thank Dr Jean Khalfa for his insights and sound advice, as well as Prof. Alison Finch, Prof. Robert Lethbridge, Dr Jann Matlock, and Prof. -

Douglass Crockwell Collection, 1897-1976, Bulk 1934-1968

Douglass Crockwell collection, 1897-1976, bulk 1934-1968 Finding aid prepared by Ken Fox, Project Archivist, George Eastman Museum, Moving Image Department, April 2015 Descriptive Summary Creator: Crockwell, Spencer Douglass, 1904-1968 Title: Douglass Crockwell collection Dates: 1897-1976, bulk 1934-1968 Physical Extent: 30.1 cubic feet Repository: Moving Image Department George Eastman Museum 900 East Avenue Rochester, NY 14607 Phone: 585-271-3361 Email: [email protected] Content Abstract: Spencer Douglass Crockwell was a commercial illustrator, experimental filmmaker, inventor, Mutoscope collector, amateur scientist, and Glens Falls, New York, resident. The Douglass Crockwell Collection contains Mr. Crockwell's personal papers, professional documents, films, Mutoscope reels, flip books, drawings, and photographs documenting his professional, civic, and personal life. Language: Collection materials are in English Location: Collection materials are located onsite. Access Restrictions: Collection is open to research upon request. Copyright: George Eastman Museum holds the rights to the physical materials but not intellectual property rights. Acquisition Information: The earliest acquisition of collection materials occurred on August 20, 1973, when one table Mutoscope and three Mutoscope reels were received by the George Eastman Museum as an unrestricted gift from Mr. Crockwell's widow. On March 22, 1974, Mrs. Crockwell transferred most of the Douglass Crockwell Collection to the Museum with the 1 understanding that one third of the collection would be received as an immediate gift. The remaining balance of the collection -- which included the films -- would be received as a loan for study purposes with the understanding it would be accessioned into the permanent collection as a gift within the next two years. -

Catalogue 143 ~ Holiday 2008 Contents

Between the Covers - Rare Books, Inc. 112 Nicholson Rd (856) 456-8008 will be billed to meet their requirements. We accept Visa, MasterCard, American Express, Discover, and Gloucester City NJ 08030 Fax (856) 456-7675 PayPal. www.betweenthecovers.com [email protected] Domestic orders please include $5.00 postage for the first item, $2.00 for each item thereafter. Images are not to scale. All books are returnable within ten days if returned in Overseas orders will be sent airmail at cost (unless other arrange- the same condition as sent. Books may be reserved by telephone, fax, or email. ments are requested). All items insured. NJ residents please add 7% sales tax. All items subject to prior sale. Payment should accompany order if you are Members ABAA, ILAB. unknown to us. Customers known to us will be invoiced with payment due in 30 days. Payment schedule may be adjusted for larger purchases. Institutions Cover verse and design by Tom Bloom © 2008 Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. Catalogue 143 ~ Holiday 2008 Contents: ................................................................Page Literature (General Fiction & Non-Fiction) ...........................1 Baseball ................................................................................72 African-Americana ...............................................................55 Photography & Illustration ..................................................75 Children’s Books ..................................................................59 Music ...................................................................................80 -

11 71 126 Bruno Adler Lotte Collein Walter Gropius Weimar in Those

11 71 126 Bruno Adler Lotte Collein Walter Gropius Weimar in Those Days Photography The Idea of the at the Bauhaus Bauhaus: The Battle 16 for New Educational Josef Albers 76 Foundations Thirteen Years Howard at the Bauhaus Dearstyne 131 Mies van der Rohe’s Hans 22 Teaching at the Haffenrichter Alfred Arndt Bauhaus in Dessau Lothar Schreyer how i got to the and the Bauhaus bauhaus in weimar 83 Stage Walter voxel 30 The Bauhaus 137 Herbert Bayer Style: a Myth Gustav Homage to Gropius Hassenpflug 89 A Look at the Bauhaus 33 Lydia Today Hannes Beckmann Driesch-Foucar Formative Years Memories of the 139 Beginnings of the Fritz Hesse 41 Dornburg Pottery Dessau Max Bill Workshop of the State and the Bauhaus the bauhaus must go on Bauhaus in Weimar, 1920-1923 145 43 Hubert Hoffmann Sandor Bortnyik 100 the revival of the Something T. Lux Feininger bauhaus after 1945 on the Bauhaus The Bauhaus: Evolution of an Idea 150 50 Hubert Hoffmann Marianne Brandt 117 the dessau and the Letter to the Max Gebhard moscow bauhaus Younger Generation Advertising (VKhUTEMAS) and Typography 55 at the Bauhaus 156 Hin Bredendieck Johannes Itten The Preliminary Course 121 How the Tremendous and Design Werner Graeff Influence of the The Bauhaus, Bauhaus Began 64 the De Stijl group Paul Citroen in Weimar, and the 160 Mazdaznan Constructivist Nina Kandinsky at the Bauhaus Congress of 1922 Interview 167 226 278 Felix Klee Hannes Meyer Lou Scheper My Memories of the On Architecture Retrospective Weimar Bauhaus 230 283 177 Lucia Moholy Kurt Schmidt Heinrich Kdnig Questions -

2015 Benefit Auction Program Preview Program Preview Program Preview Saturday, November 7 Preview Exhibition: November 2-6

2014 FINE PRINT 2014 FINE PRINT 2014 FINE PRINT AUCTION PROGRAM PREVIEW PROGRAM PREVIEW PROGRAM PREVIEW 2014 FINE PRINT 2014 FINE PRINT 2014 FINE PRINT 2015 BENEFIT AUCTION PROGRAM PREVIEW PROGRAM PREVIEW PROGRAM PREVIEW SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 7 PREVIEW EXHIBITION: NOVEMBER 2-6 2014 FINE PRINT 2014 FINE PRINT 2014 FINE PRINT PROGRAM PREVIEW PROGRAM PREVIEW PROGRAM PREVIEW WWW.SFCAMERAWORK.ORG ABOVE: CHRIS MCCAW, Sunburned GSP#815 ON COVER: PHILLIP MAISEL, (Mojave), 2014, LOT 54 Feldspar (1101), 2015, LOT 22 Chris McCaw’s Sunburn prints pare photogra- Phillip Maisel’s work lies somewhere between docu- phy down to its most basic elements—light and mentation, sculpture, photography, and collage. His time. For each unique photograph, McCaw makes working process begins with impermanent arrange- hours-long exposures onto photo-sensitive paper, ments of everyday materials – paper, glass, mirrors, allowing the sun to literally burn a trace of its tape - staged for the camera’s lens. He then makes path across the sky. This sunrise diptych was multiple adjustments – repositioning, introducing made in late winter in the Mojave. McCaw’s work or extracting various elements – and photographing has been exhibited most recently at the J. Paul each intervention in a sequence. Elements used in Getty Museum, Los Angeles; the National Gallery various stages of photographic processes (color fil- of Art, Washington, D.C.; and the Phoenix Art ters, glassine, and prints themselves) are integrated Museum. Sunburn, a monograph of his photo- back into the artwork either as part of the sculpture graphs was published by Candela Books in 2012. or as collage elements that may be re-inserted into a new, composite creation. -

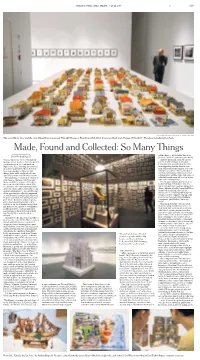

Made, Found and Collected: So Many Things

THE NEW YORK TIMES, FRIDAY, JULY 22, 2016 N C19 PHOTOGRAPHS BY NICOLE BENGIVENO/THE NEW YORK TIMES The artist Oliver Croy and the critic Oliver Elser preserved “The 387 Houses of Peter Fritz (1916-1992) Insurance Clerk from Vienna, 1993-2008.” The show includes 126 of them. Made, Found and Collected: So Many Things gallery here — in the belief that they From Weekend Page 17 prevent evil from destroying the world. Poland, where she lived. Although by And the label falls squarely on the the time of her death, in 1997, she hadn’t career of Arthur Bispo do Rosário reached her goal, she had made an (circa 1910-89), a Brazilian artist who, impressive start, shooting the interiors after reporting that he’d had a visit of 20,000 rural homes. Most, however from Christ and some angels, was com- poor, were packed to the roof with mitted to an asylum where, using un- things, their walls plastered with im- raveled clothing and rubbish, he creat- ages of pop stars and Christian saints. ed tapestries, arklike ships and a line of Documenting — which is a version of celestial formal wear, all on view in the collecting — existing collections like museum’s lobby gallery. these constitutes a genre of its own in Yet art isn’t outsider just because it the show. In a 2013 video called “The looks that way. If that were true, the Trick Brain,” the contemporary British market would have long ago jumped on artist Ed Atkins adds terrifically creepy Shinro Ohtake, a highly regarded Tokyo spoken commentary to an old film tour noise-rock musician, who has for of the personal art collection amassed decades been compiling cut-and-paste by the French Surrealist André Breton.