Alexey Brodovitch and His Influence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

He Museum of Modern Art No

he Museum of Modern Art No. 21 ?» FOR RELEASE: |l West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart Tuesday, February 28, I96T PRESS PREVIEW: Monday, February 27, I96T 11 a.m. - k p.m. HEW DOCUMENTS, an exhibition of 90 photographs by three leading representatives of a new generation of documentary photographers -- Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand — will be on view at The Museum of Modern Art from February 28 through May 7. John Szarkowski, Director of the Department of Photography, writes in his intro- this duction to the exhibition, "In the past decade/new generation of photographers has redirected the technique and aesthetic of documentary photography to more personal ends. Their aim has been not to reform life but to know it, not to persuade but to understand. The world, in spite of its terrors, is approached as the ultimate source of wonder and fascination, no less precious for being irrational and inco* herent." Their approach differs radically from the documentary photographers of the thirties and forties, when the term was relatively new. Then, photographers used their art as a tool of social reform; "it wac their hope that their pictures would make clear what was wrong with the world, and persuade their fellows to take action and change it," according to Szarkowski, "VJhat unites these three photographers," he says, "is not style or sensibility; each has a distinct and personal sense of the use of photography and the meanings of the world. What is held in common is the belief that the world is worth looking at, and the courage to look at it without theorizing," Garry Winogrand*a subjects range from a group of bathers at Eastharapton Beach on Long Island to a group of tourists at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Los Angeles and refer to much of contemporary America, from the Beverly Hilton Hotel in California to peace marchers in Cape Cod, (more) f3 -2- (21) Winograod was born in New York City in I928 and b3gan photographing while in the Air Force during the second World War. -

ABC Distribution Kaasstraat 4 2000 Antwerpen T

ABC Distribution Kaasstraat 4 2000 Antwerpen t. 03 – 231 0931 www.abc‐distribution.be info@abc‐distribution.be presenteert / présente release: 14/11/2012 Persmappen en beeldmateriaal van al onze actuele titels kan u gedownloaden van onze site: Vous pouvez télécharger les dossiers de presse et les images de nos films sur: www.abc‐distribution.be Link door naar PERS om een wachtwoord aan te vragen. Visitez PRESSE pour obtenir un mot de passe. 2 DIANA VREELAND: THE EYE HAS TO TRAVEL – synopsis nl + fr Diana Vreeland – sprankelende persoonlijkheid, mode‐icoon en hoofdredacteur – schreef geschiedenis door mode te verheffen tot kunstvorm. Vreeland zwaaide de scepter als hoofdredacteur van Harper’s Bazaar en Vogue en creëerde een lifestyle vol glamour en excentriciteit die ongekend was in haar tijd. Vreeland werd bejubeld om haar humor en vlijmscherpe uitspraken als ‘the bikini is the biggest thing since the atom bomb.’ Twiggy, Lauren Bacall, Jackie O. en Coco Chanel behoorden tot haar meest intieme vrienden. In de documentaire DIANA VREELAND: THE EYE HAS TO TRAVEL blikt The Empress of Fashion zelf terug op haar bewogen leven. De fine fleur uit de internationale modewereld komen aan het woord over deze grande dame aller tijdschriften. Met o.a. Manolo Blahnik, Lauren Hutton, Diana von Furstenberg, David Bailey en Anjelica Huston. Lengte 88min. / Taal: Engels / Land: Verenigde Staten Diana Vreeland, personnalité hors norme, brillante, excentrique, aussi charmeuse qu’impérieuse, régna 55 ans durant sur la mode et éblouit le monde par sa vision unique du style. DIANA VREELAND : THE EYE HAS TO TRAVEL est à la fois un portrait intime et un vibrant hommage à l’une des femmes exceptionnelles du XXème siècle, véritable icône dont l’influence a changé le visage de la mode, de l’art, de l’édition et de la culture en général. -

Alexey Brodovitch and Milton Glaser

Alexey Brodovitch and Milton Glaser By: Collins Ferebee and Bridget Dunne Alexey Brodovitch Alexey Brodovitch • Photographer, designer, and instructor • Born in Ogolitch, Russia in 1898 • Moved to Moscow during the Russo‐ Japanese war • Moved to France aer serving in the White Army during the Russian Civil War where he began sketching designs for texles, China, Jewelry, and Posters • Although employed by Athelia, he started his own studio L’ Atelier where he produced posters for various clients, including Union Radio Paris and the Cunard shipping company Milton Glaser Milton Glaser • Born June 26, 1929 In NYC • Graphic designer best known for his “I <3 NYC” logo • Graduated Cooper Union in 1951, as well as the Academy of Fine Arts Bologna under Giorgio Mirandi, one of the most highly respected sll life painters of his day • Taught at the Visual School of Arts and Cooper Union Brodovitch Style • Believed in the primacy of visual freshness and immediacy • He believed in simplicity by displaying elegance from the merest hint of materiality • Taught his students with ulizing Visual aids, such as French and German Magazines and oungs around town Brodovitch Brodovitch Glaser Style • Directness, Simplicity, and Originality define his works • Those who have worked with Glaser know that he is not afraid of any medium and will use whatever it takes to get the message across • One can expect to see his style range from “primive” to Avant Garde Glaser Glaser Brodovitch Type and Print Ulized strict geometric forms and basic colors Brodovitch Bodovitch Achievements • First gained recognion for winning a poster contest for the Bal Banal in 1924 • Headed The Pennsylvania Museum School of Art’s Adversing Design Department • Shot images from the Le Tricome ballet for his book Ballet, published in 1945 • Art Director of Harper’s Bazaar from 1934‐ 1958 Brodovitch Brodovitch Glaser Achievements • In 1954 Glaser Was Founder And President Of Push Pin Studios • Co‐ founder of New York Magazine • 600 Mural in IndianapolisJust To Name A Few, Here Are A List Of Glaser’s Firms clients. -

WORKS by LEGENDARY PHOTOGRAPHER HORST at the Mccord MUSEUM

WORKS BY LEGENDARY PHOTOGRAPHER HORST AT THE McCORD MUSEUM A NORTH AMERICAN EXCLUSIVE Montreal, May 12, 2015 – Between May 14, and August 23, 2015, the McCord Museum is presenting, exclusive to North America, Horst: Photographer of Style, the first major retrospective of the works of Horst P. Horst (1906-1999). This touring exhibition is produced by London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. Legendary German-American artist Horst was one of the 20th century’s most influential fashion and portrait photographers. The exhibition features more than 250 vintage shots that transcend time. In addition to the photographs, the retrospective displays sketchbooks, a short film, archival footage, contact sheets and magazines, as well as eight haute couture dresses from celebrated designers that include Chanel, Muriel Maxwell Couverture du Vogue Molyneux, Lanvin, Schiaparelli, Maggy Rouff and Vionnet, all Muriel Maxwell américain, 1er juillet 1939 from the Victoria and Albert Museum collection. Cover of American Vogue, © Condé Nast /Succession July 1, 1939 Horst © Condé Nast / Horst Estate Also included in the exhibition are a number of less well-known aspects of Horst’s work: nude studies, travel shots from the Middle East, patterns created from natural forms, interiors and portraits. It chronicles his creative process and artistic influences, touching notably on his interest in ancient Classical art, particularly Greco-Roman sculpture, the Bauhaus ideals of modern design, and Surrealism in 1930s Paris. Visitors will discover in the exhibition the legacy of a master photographer. The four primary lenders are the Horst Estate; R. J. Horst; the Condé Nast Archive in New York; and the archive of Paris Vogue. -

Vogue Magazine the Glossy Has Spawned an Industry of Imitators, Two Documentaries, a Major Hollywood Film And, Perhaps Most Enduringly, a Modern Dance Craze

Lookout By the Numbers Vogue Magazine The glossy has spawned an industry of imitators, two documentaries, a major Hollywood film and, perhaps most enduringly, a modern dance craze. Itís also gone through some serious changes over the course of its 121 years in print. In recent years, the fashion bible has traded willowy models for celebrities of all kinds, a trend that reached its apex in April when the left-leaning, Chanel-shaded Brit Anna Wintour (the magazineís seventh editor in chief) decided to put ó gasp! ó a reality star on its cover. But even with young upstarts nipping at its Manolos, the periodical that popularized tights and the L.B.D. continues to thrive under its time-tested principle. That is, while other magazines 15 teach women whatís new in fashion, Vogue teaches them whatís in vogue. Approx. age at which Anna Wintour Here, a look at the facts and figures behind fashionís foremost franchise. — JEFF OLOIZIA established her signature bob $200,000 13% Wintour’s rumoredored annual clothing allowance of covers featuring celebrities during Wintour’s first five years 916 PagesP in the Favorite cover model by editor: SeptemberSepte 2012 issue, Anna Wintour: Vogue’sVogue largest to date 93% AMBER VALLETTA Vogue’sVoVogue’gue’ longest tenuredd editors:editors: of covers featuringg celebritiesc 17x over the last five years (still on the masthead)d) Diana Vreeland: Anna Wintour – 29 years A samplingsampling BRIGITTE BAUER Phyllis Posnick – 27 years of the 19 exotic exotic & animalsanimalsimals in fashionfashi on JEAN SHRIMPTON Grace Coddington – 26 years 19x each spreadsspreads Hamish Bowles – 22 years alongsideala ongside famous famous Reigning cover queen ladies:ladies:dies: 37 CheetahC (Kim Basinger, April ‘88) Number of years the longest ElephantEle (Keira Knightley, June ‘07) 26 reigning editor in chief served (Edna Woolman Chase, 1914-1951) SkunkSk (Reese Witherspoon, June ‘03) Number of times Lauren Hutton has fronted the magazine GibbonGi (Marisa Berenson, March ‘65) 8 (Nastassja Kinski, Oct. -

A Finding Aid to the Cosmos Andrew Sarchiapone Papers, Circa 1860-2011, Bulk 1940-2011, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Cosmos Andrew Sarchiapone Papers, circa 1860-2011, bulk 1940-2011, in the Archives of American Art Hilary Price and Caroline Donadio 2016 April 21 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 5 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 5 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 7 Series 1: Biographical Material and Personal Business Records, circa 1949-2011................................................................................................................. 7 Series 2: Correspondence, 1940s-2011................................................................... 9 Series 3: Writings, circa -

Photo/Graphics Michel Wlassikoff

SYMPOSIUMS 1 Michel Frizot Roxane Jubert Victor Margolin Photo/Graphics Michel Wlassikoff Collected papers from the symposium “Photo /Graphisme“, Jeu de Paume, Paris, 20 October 2007 © Éditions du Jeu de Paume, Paris, 2008. © The authors. All rights reserved. Jeu de Paume receives a subsidy from the Ministry of Culture and Communication. It gratefully acknowledges support from Neuflize Vie, its global partner. Les Amis and Jeunes Amis du Jeu de Paume contribute to its activities. This publication has been made possible by the support of Les Amis du Jeu de Paume. Contents Michel Frizot Photo/graphics in French magazines: 5 the possibilities of rotogravure, 1926–1935 Roxane Jubert Typophoto. A major shift in visual communication 13 Victor Margolin The many faces of photography in the Weimar Republic 29 Michel Wlassikoff Futura, Europe and photography 35 Michel Frizot Photo/graphics in French magazines: the possibilities of rotogravure, 1926–1935 The fact that my title refers to technique rather than aesthetics reflects what I take to be a constant: in the case of photography (and, if I might dare to say, representation), technical processes and their development are the mainsprings of innovation and creation. In other words, the technique determines possibilities which are then perceived and translated by operators or others, notably photographers. With regard to photo/graphics, my position is the same: the introduction of photography into graphics systems was to engender new possibilities and reinvigorate the question of graphic design. And this in turn raises another issue: the printing of the photograph, which is to say, its assimilation to both the print and the illustration, with the mass distribution that implies. -

Where Diane Arbus Went

"PTOTOGRAPHY Where Diane Arbus Went A comprehensive retrospectiveprompts the author to reconsiderthe short yetpowerfully influential career of aphotographer whose 'Yfascinationwith eccentricity and masquerade brought her into an unforeseeable convergence with her era, and made her one of its essential voices." BY LEO RUBINFIEN _n Imagesfrom Diane Arbus's collage wall, including a number ofplctures tornfrom the pages of newspapers, magazines and books, several of her own roughprintsand a framedE.J. Bellocqphotograph printed by Lee Friedlander(center, at right). © 2003 The Estate ofDlaneArbus,LLC. All works this articlegelatin silver,prints. "I .1 or almostfour decades the complex, profound dedicated herself to her personal work, and by She described her investigations as adventures vision ofDianeArbus (1923-1971) has had an the decade's end she and her husband separated, that tested her courage, and as an emancipa- enormous influence on photographyand a broad though they remained married until 1969, and tion from her childhood's constrainingcomfort. one beyond it and the generalfascination with were close until the end of her life. Her essential At the same time, she worked as she wandered her work has been accompanied by an uncommon interestswere clear ofler 1956, andfor the next six freely in New York City, where ordinarypeople interest in her self Her suicide has been one, but years she photographedassiduously with a 35mm gave her some of her greatestpictures. Proposing just one, reasonfor the latter yetfor the most part camera, in locations that included Coney Island, projects to the editors of magazines that ificluded the events of her life were not extraordinary. carnivals, Huberts Museum and Flea Circus of Harper's Bazaar, Esquire and Londons Sunday Arbus's wealthy grandparentswere the found- 42nd Street, the dressing rooms offemale imper- 'Times Magazine, she was able to publish many of ers of Russek0, a Fifth Avenue department store. -

Eclectic Ease

TAKE A MEMO JEAN PAUL GAULTIER TALKS ABOUT HIS NEW A NEW BOOK COLLECTS BROOKLYN- EXHIBITION IN THE THE MEMOS FROM THE BOROUGH, AS WELL AS MADONNA, FILM AND LEGENDARY DIANA BOUND MORE. PAGE 3 VREELAND. PAGE 10 $500,000 CONTRIBUTION Ralph Boosts Initiative For NYC Manufacturing By MARC KARIMZADEH NEW YORK — Ralph Lauren has given a signifi cant boost to New York garment manufacturing. Lauren will serve as the “premier underwriter” of the new Fashion Manufacturing Initiative with WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 23, 2013 ■ $3.00 ■ WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY a $500,000 contribution from Ralph Lauren Corp. to the program, which was launched last month by WWD the Council of Fashion Designers of America and Andrew Rosen in partnership with the New York City Economic Development Corp. “I was born in New York and started my business in the Garment District here,” Lauren said. “FMI serves an important role in supporting our city, our industry and gives designers the access and oppor- tunities needed to help advance their careers while Eclectic boosting manufacturing in New York. This is some- thing I’m very proud to be a part of.” The initiative’s aim is to raise funds and create grants to help existing factories in the fi ve boroughs to update equipment, acquire new machinery and train workers, for example. Ease With the contribution, Don Baum, Ralph Lauren’s Contemporary designers are striking an senior vice president, global manufacturing and sourcing, will join FMI’s selection committee, which easy-breezy vibe for spring with loose, includes Rosen, chief executive offi cer of Theory; carefree shapes worked in a mix of cheerful CFDA ceo Steven Kolb; designer Prabal Gurung; Nanette Lepore ceo Bob Savage, and Rag & Bone de- patterns. -

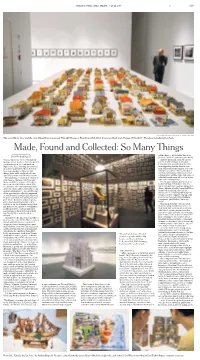

Made, Found and Collected: So Many Things

THE NEW YORK TIMES, FRIDAY, JULY 22, 2016 N C19 PHOTOGRAPHS BY NICOLE BENGIVENO/THE NEW YORK TIMES The artist Oliver Croy and the critic Oliver Elser preserved “The 387 Houses of Peter Fritz (1916-1992) Insurance Clerk from Vienna, 1993-2008.” The show includes 126 of them. Made, Found and Collected: So Many Things gallery here — in the belief that they From Weekend Page 17 prevent evil from destroying the world. Poland, where she lived. Although by And the label falls squarely on the the time of her death, in 1997, she hadn’t career of Arthur Bispo do Rosário reached her goal, she had made an (circa 1910-89), a Brazilian artist who, impressive start, shooting the interiors after reporting that he’d had a visit of 20,000 rural homes. Most, however from Christ and some angels, was com- poor, were packed to the roof with mitted to an asylum where, using un- things, their walls plastered with im- raveled clothing and rubbish, he creat- ages of pop stars and Christian saints. ed tapestries, arklike ships and a line of Documenting — which is a version of celestial formal wear, all on view in the collecting — existing collections like museum’s lobby gallery. these constitutes a genre of its own in Yet art isn’t outsider just because it the show. In a 2013 video called “The looks that way. If that were true, the Trick Brain,” the contemporary British market would have long ago jumped on artist Ed Atkins adds terrifically creepy Shinro Ohtake, a highly regarded Tokyo spoken commentary to an old film tour noise-rock musician, who has for of the personal art collection amassed decades been compiling cut-and-paste by the French Surrealist André Breton. -

DAVID ATTIE: Visual Communication MARCH 18 – MAY 27, 2021

1 David Attie, Self-Portrait, c. 1965, Vintage Gelatin Silver Print, Paper: 9” x 6.75” DAVID ATTIE: Visual Communication MARCH 18 – MAY 27, 2021 41 E 57TH S T, S U I T E 7 0 3 N E W YO R K , N Y 1 0 0 2 2 T 212.327.1482 F 212.327.1492 [email protected] URL www.keithdelellisgallery.com FINE ART PHOTOGRAPHY 2 David Attie 6 David Attie Lisette Model Leonard Bernstein, rehearsal 1972 at Carnegie Hall Vintage Gelatin Silver Print 1959 Image: 9.5” x 7.25” Vintage Gelatin Silver Print Paper: 10” x 8” Image/Paper: 6.5” x 13.5” 3 David Attie 7 David Attie Brodovitch Design Laboratory, Truman Capote (Holiday Richard Avedon’s Studio Magazine) c. 1957 1958 Vintage Gelatin Silver Print Vintage Gelatin Silver Print Image: 10.5” x 13.5” Image/Paper: 11.5” x 10” Paper: 11” x 14” 4 David Attie 8 David Attie Jerry Leiber & Mike Stoller David Merrick (Vogue (Vogue Magazine) Magazine) 1959 1959 Vintage Gelatin Silver Print Vintage Gelatin Silver Print Image/Paper: 12.75” x 10.5” Image/Paper: 9” x 7.25” 5 David Attie 9 David Attie Lorraine Hansberry at her Untitled (Pharmaceuticals) Bleecker Street apartment c. 1958 (Vogue Magazine) Vintage Gelatin Silver Print 1959 Image: 8.5” x 19” Vintage Gelatin Silver Print Mount: 16” x 20” Image: 11.75” x 9” Paper: 14” x 10.5” *Prices do not include framing Page 2 of 5 41 E 57TH S T, S U I T E 7 0 3 N E W YO R K , N Y 1 0 0 2 2 T 212.327.1482 F 212.327.1492 [email protected] URL www.keithdelellisgallery.com FINE ART PHOTOGRAPHY 10 David Attie 14 David Attie Untitled (Pageant Magazine) Saloon Society c. -

Alexey Brodovitch Collection Has Been Developed from the Gifts of Many Donors

Alexey Brodovitch (1898 – 1971) Processed by: Heidi Halton, Project Archivist August 2001 Wallace Library Archives and Special Collections Rochester Institute of Technology Rochester, New York 14623-0887 The Alexey Brodovitch Collection has been developed from the gifts of many donors. Former students and colleagues of Brodovitch whose work is included in the collection, or their families, have been gracious enough to donate their work and related material to the Archives and Special Collections at Wallace Library. (Much of this material was originally collected to be included in the exhibit, “The Enduring Legacy of Alexey Brodovitch”) The collection is housed in 13 flat storage boxes, 5 small flip-top boxes, 1 document box, 1 notebook, 2 large storage boxes and 1 oversize flat-file drawer. 1 Photographic Material Boxes 1 – 11 Pages 3 – 6 See following page for listing of photographers whose work is included in each box Bibliographic/Biographic Files Bibliographic Material Box 12 Page 7 Brodovitch, Grundberg Production Files Box 13 Page 7 Exhibition, “Astonish Me!” Boxes 14 – 15 Page 7 Audio Material Brodovitch Classes Box 16 Page 8 Interviews/Conversations Box 17 Page 8 (Original Recordings) Box 18 Page 9 Video Material Box 19 Page 9 Karim Sednaoui Research Material Box 20 Page 9 Slides Box 21 Page 9 Notebook Page 9 Poster, “Hommage à Alexey Brodovitch” Flat File Page 9 Publications by Brodovitch The following publications are integrated into the rare book collection Ballet: 104 Photographs. New York: J.J. Augustin, 1945. RARE GV1787.B68 1945 Harper’s Bazaar RARE TT500.H3 Junior Bazaar RARE TT500.J85 Portfolio v.