Photo/Graphics Michel Wlassikoff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Image Carrier Poster

55899-11_MOP_nwsltr_poster_Winter11_v2_Layout 1 2/11/11 2:25 PM Page 1 The Museum of Printing, North Andover, MA and the Image Carrier www.museumofprinting.org Relief printing Wood cuts and wood engravings pre-dated moveable type. Called “xylographic printing,” it was used before Gutenberg for illustrations, playing cards, and small documents. Moveable type allowed corrections and editing. A wood engraving uses the end grain, where a wood cut uses the plank grain. Polymer plates are made from digital files which drive special engraving machines to produce relief plates. These plates are popular with many of today’s letterpress printers who produce invitations, and collectible prints. Metal relief cylinders were used to print repetitive designs, such as those on wrap - ping paper and wall paper. In the 1930s, the invention of cellophane led to the development of the anilox roller and flexographic printing. Today, flexography prints most of the flexible packaging film which accounts for about half of all packaged products. Hobbyists, artists, and printmakers cut away non-printing areas on sheets of linoleum to create relief surfaces. Wood cut Wood engraving and Metal plate Relief cylinder Flexographic plate Linoleum cut Foundry type began with Gutenberg and evolved through Jenson, Garamond, Moveable type Caslon and many others. Garamond was the first printer to cast type that was sold to other printers. By the 1880s there were almost 80 foundries in the U.S. One newspaper could keep one foundry in business. Machine typesetting changed the status quo and the Linotype had an almost immediate effect on type foundries. Twenty-three foundries formed American Type Founders in 1890. -

He Museum of Modern Art No

he Museum of Modern Art No. 21 ?» FOR RELEASE: |l West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart Tuesday, February 28, I96T PRESS PREVIEW: Monday, February 27, I96T 11 a.m. - k p.m. HEW DOCUMENTS, an exhibition of 90 photographs by three leading representatives of a new generation of documentary photographers -- Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand — will be on view at The Museum of Modern Art from February 28 through May 7. John Szarkowski, Director of the Department of Photography, writes in his intro- this duction to the exhibition, "In the past decade/new generation of photographers has redirected the technique and aesthetic of documentary photography to more personal ends. Their aim has been not to reform life but to know it, not to persuade but to understand. The world, in spite of its terrors, is approached as the ultimate source of wonder and fascination, no less precious for being irrational and inco* herent." Their approach differs radically from the documentary photographers of the thirties and forties, when the term was relatively new. Then, photographers used their art as a tool of social reform; "it wac their hope that their pictures would make clear what was wrong with the world, and persuade their fellows to take action and change it," according to Szarkowski, "VJhat unites these three photographers," he says, "is not style or sensibility; each has a distinct and personal sense of the use of photography and the meanings of the world. What is held in common is the belief that the world is worth looking at, and the courage to look at it without theorizing," Garry Winogrand*a subjects range from a group of bathers at Eastharapton Beach on Long Island to a group of tourists at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Los Angeles and refer to much of contemporary America, from the Beverly Hilton Hotel in California to peace marchers in Cape Cod, (more) f3 -2- (21) Winograod was born in New York City in I928 and b3gan photographing while in the Air Force during the second World War. -

Kemble Z3 Ephemera Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c818377r No online items Kemble Ephemera Collection Z3 Finding aid prepared by Jaime Henderson California Historical Society 678 Mission Street San Francisco, CA, 94105-4014 (415) 357-1848 [email protected] 2013 Kemble Ephemera Collection Z3 Kemble Z3 1 Title: Kemble Z3 Ephemera Collection Date (inclusive): 1802-2013 Date (bulk): 1900-1970 Collection Identifier: Kemble Z3 Extent: 185 boxes, 19 oversize boxes, 4 oversize folder (137 linear feet) Repository: California Historical Society 678 Mission Street San Francisco, CA 94105 415-357-1848 [email protected] URL: http://www.californiahistoricalsociety.org Location of Materials: Collection is stored onsite. Language of Materials: Collection materials are primarily in English. Abstract: The collection comprises a wide variety of ephemera pertaining to printing practice, culture, and history in the Western Hemisphere. Dating from 1802 to 2013, the collection includes ephemera created by or relating to booksellers, printers, lithographers, stationers, engravers, publishers, type designers, book designers, bookbinders, artists, illustrators, typographers, librarians, newspaper editors, and book collectors; bookselling and bookstores, including new, used, rare and antiquarian books; printing, printing presses, printing history, and printing equipment and supplies; lithography; type and type-founding; bookbinding; newspaper publishing; and graphic design. Types of ephemera include advertisements, announcements, annual reports, brochures, clippings, invitations, trade catalogs, newspapers, programs, promotional materials, prospectuses, broadsides, greeting cards, bookmarks, fliers, business cards, pamphlets, newsletters, price lists, bookplates, periodicals, posters, receipts, obituaries, direct mail advertising, book catalogs, and type specimens. Materials printed by members of Moxon Chappel, a San Francisco-area group of private press printers, are extensive. Access Collection is open for research. -

Jan Tschichold and the New Typography Graphic Design Between the World Wars February 14–July 7, 2019

Jan Tschichold and the New Typography Graphic Design Between the World Wars February 14–July 7, 2019 Jan Tschichold. Die Frau ohne Namen (The Woman Without a Name) poster, 1927. Printed by Gebrüder Obpacher AG, Munich. Photolithograph. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Peter Stone Poster Fund. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY. Jan Tschichold and the New February 14– Typography: Graphic Design July 7, 2019 Between the World Wars Jan Tschichold and the New Typography: Graphic Design Between the World Wars, a Bard Graduate Center Focus Project on view from February 14 through July 7, 2019, explores the influence of typographer and graphic designer Jan Tschichold (pronounced yahn chih-kold; 1902-1974), who was instrumental in defining “The New Typography,” the movement in Weimar Germany that aimed to make printed text and imagery more dynamic, more vital, and closer to the spirit of modern life. Curated by Paul Stirton, associate professor at Bard Graduate Center, the exhibition presents an overview of the most innovative graphic design from the 1920s to the early 1930s. El Lissitzky. Pro dva kvadrata (About Two Squares) by El Lissitzky, 1920. Printed by E. Haberland, Leipzig, and published by Skythen, Berlin, 1922. Letterpress. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, While writing the landmark book Die neue Typographie Jan Tschichold Collection, Gift of Philip Johnson. Digital Image © (1928), Tschichold, one of the movement’s leading The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. designers and theorists, contacted many of the fore- most practitioners of the New Typography throughout Europe and the Soviet Union and acquired a selection The New Typography is characterized by the adoption of of their finest designs. -

Graphic Design in the Postmodern Era

Graphic Design in the Postmodern Era By Mr. Keedy This essay was based on lectures presented at FUSE 98, San Francisco, May 28, and The AIGA National Student Design Conference, CalArts, June 14, 1998. It was first published in 1998 in Emigre 47. Any discussion of postmodernism must be preceded by at least a provisional definition of modernism. First there is modernism with a capital "M," which designates a style and ideology and that is not restricted to a specific historical moment or geographical location. Modernist designers from the Bauhaus in Germany, the De Style in Holland, and Constructivism in Russia, share essentially the same Modernist ideology as designers like Paul Rand, Massimo Vignelli, and Eric Spiekermann. Its primary tenet is that the articulation of form should always be derived from the programmatic dictates of the object being designed. In short, form follows function. Modernism was for the most part formed in art schools, where the pedagogical strategies were developed that continue to this day in design schools. It is a formalist, rationalist, visual language that can be applied to a wide range of circumstances. All kinds of claims can and have been made in an effort to keep Modernism eternally relevant and new. The contradiction of being constant, yet always new, has great appeal for graphic designers, whose work is so ephemeral. Then there is the modern, with a small "m." It is often confused with Modernism with a big M, but being a modern designer simply means being dedicated to working in a way that is contemporary and innovative, regardless of what your particular stylistic or ideological bias may be. -

The Inflow and Adaptation of Russian Constructivism on the Korean Typographic Culture in the 1920S–1930S

The inflow and adaptation of Russian Constructivism on the Korean typographic culture in the 1920s–1930s Sun-A Jeong / Min-Soo Kim / Seoul National University / Seoul / Korea Blucher Design Abstract Proceedings November 2016, The aim of this study is researching the interaction between Russian constructivist graphic im- Number 1, Volume 1 http://www.proceeding age and the East Asian typography, particularly Korean typography which has different features, s.blucher.com.br/articl compared to Western letters. For this purpose, graphic design that appeared in media such as e-list/icdhs2016/list newspapers, magazines and books during the 1920-30s in Korea is investigated. In conclusion, Russian constructivist images in Korea were composed with traditional calligraphy and created distinctive visual culture because of the political and economic colonial condition at that time, while constructivist images in Russia and Europe were used mainly with sanserif typography that considered to have international characteristic. Keywords Constructivism, Korean typography, Korean design history, sanserif typography, modernity Introduction Russian Constructivism was active around the time of the 1917 Bolshevist Revolution. Constructivism represented the “new age” brought about by the Bolshevic revolution. This style’s character was revolutionary, radical, and connected to other avant-garde European artistic movements that sought experimentation and innova- tion, including Dadaism, Futurism, and De Stijl. Meanwhile, the world was undergoing the reorganization of political structures after WW1. “Modernization” was also pursued in Korea, a colony of the Japanese Empire, as it had the will needed by weaker countries to survive independently among world powers. Consequently, different ideologies clashed over the nation’s direction. -

Alexey Brodovitch and Milton Glaser

Alexey Brodovitch and Milton Glaser By: Collins Ferebee and Bridget Dunne Alexey Brodovitch Alexey Brodovitch • Photographer, designer, and instructor • Born in Ogolitch, Russia in 1898 • Moved to Moscow during the Russo‐ Japanese war • Moved to France aer serving in the White Army during the Russian Civil War where he began sketching designs for texles, China, Jewelry, and Posters • Although employed by Athelia, he started his own studio L’ Atelier where he produced posters for various clients, including Union Radio Paris and the Cunard shipping company Milton Glaser Milton Glaser • Born June 26, 1929 In NYC • Graphic designer best known for his “I <3 NYC” logo • Graduated Cooper Union in 1951, as well as the Academy of Fine Arts Bologna under Giorgio Mirandi, one of the most highly respected sll life painters of his day • Taught at the Visual School of Arts and Cooper Union Brodovitch Style • Believed in the primacy of visual freshness and immediacy • He believed in simplicity by displaying elegance from the merest hint of materiality • Taught his students with ulizing Visual aids, such as French and German Magazines and oungs around town Brodovitch Brodovitch Glaser Style • Directness, Simplicity, and Originality define his works • Those who have worked with Glaser know that he is not afraid of any medium and will use whatever it takes to get the message across • One can expect to see his style range from “primive” to Avant Garde Glaser Glaser Brodovitch Type and Print Ulized strict geometric forms and basic colors Brodovitch Bodovitch Achievements • First gained recognion for winning a poster contest for the Bal Banal in 1924 • Headed The Pennsylvania Museum School of Art’s Adversing Design Department • Shot images from the Le Tricome ballet for his book Ballet, published in 1945 • Art Director of Harper’s Bazaar from 1934‐ 1958 Brodovitch Brodovitch Glaser Achievements • In 1954 Glaser Was Founder And President Of Push Pin Studios • Co‐ founder of New York Magazine • 600 Mural in IndianapolisJust To Name A Few, Here Are A List Of Glaser’s Firms clients. -

Type Design for Typewriters: Olivetti by María Ramos Silva

Type design for typewriters: Olivetti by María Ramos Silva Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the MA in Typeface Design Department of Typography & Graphic Communication University of Reading, United Kingdom September 2015 The word utopia is the most convenient way to sell off what one has not the will, ability, or courage to do. A dream seems like a dream until one begin to work on it. Only then it becomes a goal, which is something infinitely bigger.1 -- Adriano Olivetti. 1 Original text: ‘Il termine utopia è la maniera più comoda per liquidare quello che non si ha voglia, capacità, o coraggio di fare. Un sogno sembra un sogno fino a quando non si comincia da qualche parte, solo allora diventa un proposito, cio è qualcosa di infinitamente più grande.’ Source: fondazioneadrianolivetti.it. -- Abstract The history of the typewriter has been covered by writers and researchers. However, the interest shown in the origin of the machine has not revealed a further interest in one of the true reasons of its existence, the printed letters. The following pages try to bring some light on this part of the history of type design, typewriter typefaces. The research focused on a particular company, Olivetti, one of the most important typewriter manufacturers. The first two sections describe the context for the main topic. These introductory pages explain briefly the history of the typewriter and highlight the particular facts that led Olivetti on its way to success. The next section, ‘Typewriters and text composition’, creates a link between the historical background and the machine. -

Download Futura Font Word

1 / 5 Download Futura Font Word Futuristic Fonts Download Free futuristic fonts at UrbanFonts.com Our site carries ... '80s generator gives your words a neon retro tribute Oct 07, 2016 · Well, if you ... Futuristic Logos Futura Fonts generator tool will let you convert simple and .... Download Futura fonts from UrbanFonts.com for PC and Mac. Futura EF Fonts Free ... Futura Lt Font. How to Install Futura Font in Adobe, Ms Word, Mac or Pc?. 11 Free Chrome Graphics Generators Welcome to MyFonts, the #1 place to download great @font-face webfonts and desktop fonts: classics (Baskerville, Futura, .... Mar 12, 2020 — Want to use beautiful custom fonts in your WordPress theme? ... First thing you need to do is download the font that you like in a web format.. Download Futura PT font (22 styles). Futura PT FuturaPTBold.otf 126 Kb | Futura PT Bold Italic FuturaPTBoldOblique.otf 125 Kb | Futura PT FuturaPTBook.otf ... Download Futura PT Font click here: https://windows10freeapps.com/futura-pt-font-free-download .... Free Font for Designers! High quality design resources for free. And helps introduce first time customers to your products with free fonts downloads and allow .... I'll use Futura PT Heavy which I downloaded from Adobe Typekit, but any font will work: ... This Font used for copy and paste and also for word generator.. Sep 23, 2011 — This is the page of Futura font. You can download it for free and without registration here. This entry was published on Friday, September 23rd .... ... the text it generates may look similar to text generated using the HTML or tags or the CSS attributes font-weight: bold or font-style: italic , it isn't. -

Progress in Printing and the Graphic Arts During the Victorian

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Ik Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924032192373 Sir G. Hayter, R./l. Bet* Majesty Queen Tictorta in Coronation Robes. : progress in printing and the 6raphic Hrts during the Victorian Gra. "i BY John Southward, Author of "Practical Printing"; "Modern Printing"; "The Principles and Progress of Printing Machinery"; the Treatise on "Modern Typography" in the " EncyclopEedia Britannica" Cgtii Edition); "Printing" and "Types" in "Chambers's Encyclopaedia" (New Edition); "Printing" in "Cassell's Storehouse of General Information"; "Lessons on Printing" in Cassell's New Technical Educator," &c. &c. LONDON SiMPKiN, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co. Ltd. 1897. X^he whole of the Roman Cypc in tbta Booh has been set up by the Linotj^pe Composing Machine, and machined direct from the Linotj'pc Bars by 6eo. CH. loncs, Saint Bride Rouse, Dean Street, fetter Lane, London, e.C. ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ W Contents. ^^ Progress in Jobbing Printing Chapter I. Progress in Newspaper Printing Chapter II. Progress in Book Printing - Chapter III. Printing by Hand Press Chapter IV. Printing by Power Press Chapter V. The Art of the Compositor Chapter VI. Type-Founding Chapter VII. Stereotyping and Electrotyping Chapter VIII. Process Blocks Chapter IX. Ink Manufacture Chapter X. Paper-Making Chapter XI. Description of the Illustrations Chapter XII. ^pj progress in printing peculiarity about it It is not paid for by the person who is to become its possessor. -

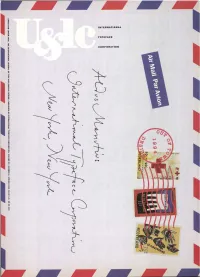

INTERNATIONAL TYPEFACE CORPORATION, to an Insightful 866 SECOND AVENUE, 18 Editorial Mix

INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION TYPEFACE UPPER AND LOWER CASE , THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF T YPE AND GRAPHI C DESIGN , PUBLI SHED BY I NTE RN ATIONAL TYPEFAC E CORPORATION . VO LUME 2 0 , NUMBER 4 , SPRING 1994 . $5 .00 U .S . $9 .90 AUD Adobe, Bitstream &AutologicTogether On One CD-ROM. C5tta 15000L Juniper, Wm Utopia, A d a, :Viabe Fort Collection. Birc , Btarkaok, On, Pcetita Nadel-ma, Poplar. Telma, Willow are tradmarks of Adobe System 1 *animated oh. • be oglitered nt certain Mrisdictions. Agfa, Boris and Cali Graphic ate registered te a Ten fonts non is a trademark of AGFA Elaision Miles in Womb* is a ma alkali of Alpha lanida is a registered trademark of Bigelow and Holmes. Charm. Ea ha Fowl Is. sent With the purchase of the Autologic APS- Stempel Schnei Ilk and Weiss are registimi trademarks afF mdi riot 11 atea hmthille TypeScriber CD from FontHaus, you can - Berthold Easkertille Rook, Berthold Bodoni. Berthold Coy, Bertha', d i i Book, Chottiana. Colas Larger. Fermata, Berthold Garauannt, Berthold Imago a nd Noire! end tradematts of Bern select 10 FREE FONTS from the over 130 outs Berthold Bodoni Old Face. AG Book Rounded, Imaleaa rd, forma* a. Comas. AG Old Face, Poppl Autologic typefaces available. Below is Post liedimiti, AG Sitoploal, Berthold Sr tapt sad Berthold IS albami Book art tr just a sampling of this range. Itt, .11, Armed is a trademark of Haas. ITC American T}pewmer ITi A, 31n. Garde at. Bantam, ITC Reogutat. Bmigmat Buick Cad Malt, HY Bis.5155a5, ITC Caslot '2114, (11 imam. -

The Urban and Cultural Climate of Rotterdam Changed Radically Between 1970 and 2000. Opinions Differ About What the Most Importa

The urban and cultural climate of Rotterdam changed radically between 1970 and 2000. Opinions differ about what the most important changes were, and when they occurred. Imagine a Metropolis shows that it was first and foremost a new perspective on Rotterdam that stimulated the development of the city during this period. If the Rotterdam of 1970 was still a city with an identity crisis that wanted to be small rather than large and cosy rather than commercial, by 2000 Rotterdam had the image of the most metropolitan of all Dutch cities. Artists and other cultural practitioners – a group these days termed the ‘creative class’ – were the first to advance this metropolitan vision, thereby paving the way for the New Rotterdam that would begin to take concrete shape at the end of the 1980s. Imagine a Metropolis goes on to show that this New Rotterdam is returning to its nineteenth-century identity and the developments of the inter-war years and the period of post-war reconstruction. For Nina and Maria IMAGINE A METROPOLIS ROTTERDAM’S CREATIVE CLASS, 1970-2000 PATRICIA VAN ULZEN 010 Publishers, Rotterdam 2007 This publication was produced in association with Stichting Kunstpublicaties Rotterdam. On February 2, 2007, it was defended as a Ph.D. thesis at the Erasmus University, Rotterdam. The thesis supervisor was Prof. Dr. Marlite Halbertsma. The research and this book were both made possible by the generous support of the Faculty of History and Arts at the Erasmus University Rotterdam, G.Ph. Verhagen-Stichting, Stichting Kunstpublicaties Rotterdam, J.E. Jurriaanse Stichting, Prins Bernhard Cultuurfonds Zuid-Holland and the Netherlands Architecture Fund.