Prints from the Thomas Walther Collection and German Exhibitions Around 1930

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jan Tschichold and the New Typography Graphic Design Between the World Wars February 14–July 7, 2019

Jan Tschichold and the New Typography Graphic Design Between the World Wars February 14–July 7, 2019 Jan Tschichold. Die Frau ohne Namen (The Woman Without a Name) poster, 1927. Printed by Gebrüder Obpacher AG, Munich. Photolithograph. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Peter Stone Poster Fund. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY. Jan Tschichold and the New February 14– Typography: Graphic Design July 7, 2019 Between the World Wars Jan Tschichold and the New Typography: Graphic Design Between the World Wars, a Bard Graduate Center Focus Project on view from February 14 through July 7, 2019, explores the influence of typographer and graphic designer Jan Tschichold (pronounced yahn chih-kold; 1902-1974), who was instrumental in defining “The New Typography,” the movement in Weimar Germany that aimed to make printed text and imagery more dynamic, more vital, and closer to the spirit of modern life. Curated by Paul Stirton, associate professor at Bard Graduate Center, the exhibition presents an overview of the most innovative graphic design from the 1920s to the early 1930s. El Lissitzky. Pro dva kvadrata (About Two Squares) by El Lissitzky, 1920. Printed by E. Haberland, Leipzig, and published by Skythen, Berlin, 1922. Letterpress. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, While writing the landmark book Die neue Typographie Jan Tschichold Collection, Gift of Philip Johnson. Digital Image © (1928), Tschichold, one of the movement’s leading The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. designers and theorists, contacted many of the fore- most practitioners of the New Typography throughout Europe and the Soviet Union and acquired a selection The New Typography is characterized by the adoption of of their finest designs. -

Photo/Graphics Michel Wlassikoff

SYMPOSIUMS 1 Michel Frizot Roxane Jubert Victor Margolin Photo/Graphics Michel Wlassikoff Collected papers from the symposium “Photo /Graphisme“, Jeu de Paume, Paris, 20 October 2007 © Éditions du Jeu de Paume, Paris, 2008. © The authors. All rights reserved. Jeu de Paume receives a subsidy from the Ministry of Culture and Communication. It gratefully acknowledges support from Neuflize Vie, its global partner. Les Amis and Jeunes Amis du Jeu de Paume contribute to its activities. This publication has been made possible by the support of Les Amis du Jeu de Paume. Contents Michel Frizot Photo/graphics in French magazines: 5 the possibilities of rotogravure, 1926–1935 Roxane Jubert Typophoto. A major shift in visual communication 13 Victor Margolin The many faces of photography in the Weimar Republic 29 Michel Wlassikoff Futura, Europe and photography 35 Michel Frizot Photo/graphics in French magazines: the possibilities of rotogravure, 1926–1935 The fact that my title refers to technique rather than aesthetics reflects what I take to be a constant: in the case of photography (and, if I might dare to say, representation), technical processes and their development are the mainsprings of innovation and creation. In other words, the technique determines possibilities which are then perceived and translated by operators or others, notably photographers. With regard to photo/graphics, my position is the same: the introduction of photography into graphics systems was to engender new possibilities and reinvigorate the question of graphic design. And this in turn raises another issue: the printing of the photograph, which is to say, its assimilation to both the print and the illustration, with the mass distribution that implies. -

ANTON STANKOWSKI “What If…?” (Was Ist Wenn) / 38 Variations on a Photograph & Selected Vintage Prints, 1925-1953 November 5 – December 23, 2015

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ANTON STANKOWSKI “What if…?” (Was ist wenn) / 38 variations on a photograph & selected vintage prints, 1925-1953 November 5 – December 23, 2015 Deborah Bell Photographs is pleased to present vintage photographs and photo-collages by Anton Stankowski (German, born 1906 in Gelsenkirchen; died 1998 in Stuttgart). During his illustrious career as a photographer and graphic designer, art director for periodicals and a creator of corporate logos, Stankowski was also a prolific abstract painter whose work shares strong similarities with that of his Swiss contemporary, Max Bill. To most Americans, Stankowski is infamous for the clean, minimal logo he designed for Deutsche Bank in 1974 at the age of 68: a simple diagonal stroke contained within an open square. He is also renowned for his 1968 design of the “Berlin Layout,” the graphic identity for the city of Berlin. The exhibition will feature two aspects of Stankowski’s work with photography: his earliest photographs, dating from 1925-1938; and the suite entitled Was ist wenn (What if…?), a sequence of 38 variations on one image that he conceived and re-worked between 1932 and 1953. The basis of this series is a single photograph, dating from 1932, of a tailor’s form bearing a man’s suit jacket. Stankowski referred to these groups of sequences as “visual plans.” Through darkroom manipulation such as image-reversal, solarization, montage, enlargement of details, multiple exposure, printing the negative through decorative screens, and reassembling the prints in hand- colored photo-collages, he created 38 variations on the original photograph. The son of a miner, Stankowski received his artistic training in 1920-26 at a Düsseldorf studio specializing in church painting and decorative painting. -

Avant-Garde and Contemporary Art Books & Ephemera

Avant-garde and Contemporary Art Books & Ephemera Sanctuary Books [email protected] (212) 861-1055 2 [Roh, Franz and Jan Tschichold] foto-auge / oeil et photo / photo-eye. Akademischer Verlag Dr. Fritz Wedekind & Co., Stuttgart, 1929. Paperback. 8.25 x 11.5”. Condition: Good. First Edition. 76 photos of the period by Franz Roh and Jan Tschichold, with German, French and English text, 18pp. of introductory text and 76 photographs and photographic experiments (one per page with captions for each) with a final page of photographers addresses at the back. Franz Roh introduction: “Mechanism and Expression: The Essence and Value of Photography”. Cover and interior pages designed by Jan Tschichold, Munich featuring El Lissitzky’s 1924 self-portrait, “The Constructor” on the cover. One of the most important and influential publications about modern photography and the New Vision published to accompany Stuttgart’s 1929 Film und Foto exhibition with examples by but not limited to: Eugene Atget, Andreas Feininger, Florence Henri, Lissitzky, Max Burchartz, Max Ernst, George Grosz and John Heartfield, Hans Finsler, Tschichold, Vordemberge Gildewart, Man Ray, Herbert Bayer, Edward and Brett Weston, Piet Zwart, Moholy-Nagy, Renger-Patzsch, Franz Roh, Paul Schuitema, Umbo and many others. A very good Japanese- bound softcover with soiling to the white pictorial wrappers and light wear near the margins. Spine head/heel chipped with paper loss and small tears and splits. Interior pages bright and binding tight. (#KC15855) $750.00 1 Toyen. Paris, 1953. May 1953, Galerie A L’ Etoile Scellee, 11, 3 Rue du Pre aux Clercs, Paris 1953. Ephemera, folded approx. -

The Poetics of Eye and Lens

The Poetics of Eye and Lens Michel Frizot This study arose from the observation of a selection of pictures in the Thomas Walther Collection at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, mainly dating from the 1920s, which give a central role to the human eye gazing at the viewer. The prevalence of this theme in the Walther Collection emphasizes the conceptual allegiance between this collection and the New Vision. An idea, typical of the New Vision, emerges from these pictures — a concept of the new medium of photography and its relationship to the eye and the hand. In this concept, the photographic record- ing process fully replaces the hand’s gesture, and the eye’s optical role is transferred to the lens. This model — the analogy of the eye and lens — dates back to the seventeenth century, when it arose in relation to the camera obscura. It is an analogy between the structure of the eye, as observed by dissection, and that of the camera obscura, which was designed in imitation of the eye (with the chamber’s lens equivalent to the lens of the eye).1 In the early days of photo- graphy, when the camera obscura was adapted from its role as an aid to drawing to instead directly record an image on a photosensitive surface, the analogy became even more relevant, and it was broadly explored by commentators on the new medium. It reappeared in the context of the 1920s avant-garde in a more theoretical and technological form, as an eye-lens analogy and a new eye-photograph combina- tion: one of the artistic developments of modernity. -

Modern Photographs the Thomas Walther Collection 1909 – 1949

abbaspour Modern Photographs Daffner The Thomas Walther Collection hambourg 1909 – 1949 Modern Photographs OBJECT Mitra Abbaspour is Associate Curator of Photography, The period between the first and second world wars saw The Museum of Modern Art. a dynamic explosion of photographic vision on both sides of the Atlantic. Imaginative leaps fused with tech- Lee Ann Daffner is Andrew W. Mellon Conservator of nological ones, such as the introduction of small, fast, Photography, The Museum of Modern Art. easily portable cameras, to generate many novel ways Maria Morris Hambourg, the founding curator of the of taking and making images. These developments— Department of Photographs at The Metropolitan which constitute a key moment in modern art, and are Museum of Art, is Senior Curator for the Walther project, the foundation of today’s photo-based world—are dra- The Museum of Modern Art. matically captured in the 341 photographs in the Thomas Walther Collection at The Museum of Modern Art. Object:Photo explores these brilliant images using Quentin Bajac is Joel and Anne Ehrenkranz Chief Curator : The Thomas Walther Collection Collection Walther Thomas The a new approach: instead of concentrating on their con- of Photography, The Museum of Modern Art. tent it also considers them as objects, as actual, physical PHOTO Jim Coddington is Agnes Gund Chief Conservator, the things created by individuals using specific techniques Department of Conservation, The Museum of Modern Art. at particular places and times, each work with its own unique history. Essays by both conservators and histori- Ute Eskildsen is Deputy Director and Head of ans provide new insight into the material as well as the Photography emeritus, Museum Folkwang, Essen. -

Wilhelm Arntz Papers, 1898-1986

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt8d5nf2w0 No online items INVENTORY OF THE WILHELM ARNTZ PAPERS, 1898-1986 Finding aid prepared by Isabella Zuralski. INVENTORY OF THE WILHELM 840001 1 ARNTZ PAPERS, 1898-1986 Descriptive Summary Title: Wilhelm Arntz papers Date (inclusive): 1898-1986 Number: 840001 Creator/Collector: Arntz, Wilhelm F. Physical Description: 159.0 linear feet(294 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, California, 90049-1688 (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Comprehensive research collection on twentieth century art, especially German Expressionism, compiled by the art expert Wilhelm Friedrich Arntz. A vast portion of the collection consists of research files on individual artists. Of particular interest are files concerning the so-called degenerate art campaign by the Nazis and the recovery of confiscated artwork after the World war II. Extensive material documents Arntz's professional activities. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in German Biographical/Historical Note Wilhelm Friedrich Arntz (1903-1985) was a German lawyer, art expert and independent researcher of twentieth century art. He was also one of the early collectors of German Expressionism. Parallel to collecting artworks, he aquired publications on 20th century art and compiled a wealth of archival material, including newspaper clippings, correspondence of artists, art historians and dealers, and ephemeral items such as invitations to exhibition openings. Trained as a lawyer, Arntz began his professional career as political editor for the newspaper Frankurter Generalanzeiger, but he lost his job in 1933 after the Nazis came to power. -

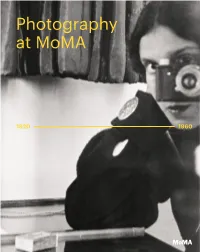

Read a Free Sample

Photography at MoMA Contributors Quentin Bajac is The Joel and Anne Ehrenkranz Chief Curator of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Museum of Modern Art draws upon the exceptional depth of its collection to tell a new history of photography in the three-volume series Photography at MoMA. Douglas Coupland is a Vancouver-based artist, writer, and cultural critic. The works in Photography at MoMA: 1920–1960 chart the explosive development Lucy Gallun is Assistant Curator in the Department of the medium during the height of the modernist period, as photography evolved of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, from a tool of documentation and identification into one of tremendous variety. New York. The result was nothing less than a transformed rapport with the visible world: Roxana Marcoci is Senior Curator in the Department Walker Evans's documentary style and Dora Maar's Surrealist exercises in chance; of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, El Lissitzky's photomontages and August Sander's unflinching objectivity; New York. the iconic news images published in the New York Times and Man Ray's darkroom experiments; Tina Modotti's socioartistic approach and anonymous snapshots Sarah Hermanson Meister is Curator in the Department of Photography at The Museum taken by amateur photographers all over the world. In eight chapters arranged of Modern Art, New York. by theme, this book presents more than two hundred artists, including Berenice Abbott, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Geraldo de Barros, Margaret Bourke-White, Kevin Moore is an independent curator, writer, Bill Brandt, Claude Cahun, Harry Callahan, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Roy DeCarava, and advisor in New York. -

Review of Jeremy Aynsley, Graphic Design in Germany, 1890–1945

Jeremy Aynsley, Graphic Design in Germany 1890-1945. Thames & Hudson, 2000. 239 pp. 253 illustrations. ISBN 0-500-51007-5 Reviewed by Victor Margolin The history of Germany from its unification by Bismark in 1871 to the end of World War II is usually divided by scholars into three periods—the Kaiserzeit or time of the kaisers, which lasted until the end of World War I; the Weimar Republic, born of the desire to forge a modern democracy from the ashes of the war; and finally Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich, which sought to restore Germany to its past glory at the expense of all who did not fit the regime’s narrow definition of an Aryan German. Within each period, cultural activity differed significantly, although there were some overlapping strands that served as lines of continuity between periods. Thomas Mann, for example, a well-known novelist before World War I, continued to gain in reputation during the Weimar years, although his literary style was more traditional than that of many Weimar authors. Likewise, Hitler retained some of the strong manifestations of modernity that flourished in the Weimar Republic even though he vowed a return to more conservative cultural traditions that had been marginalized or rejected in the Weimar years. The diverse forms of cultural practice in Germany from Bismark’s time to the end of World War II have been relatively well documented, particularly in literature, art, architecture, film, theater, and music. However, with the exception of the vast and ever expanding literature on the Bauhaus, comparatively little has been written about German design, particularly in English. -

Read a Free Sample

ENGINEER AGITATOR CONSTRUCTOR THE ARTIST REINVENTED, 1918–1939 THE MERRILL C. BERMAN COLLECTION JODI HAUPTMAN ADRIAN SUDHALTER THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK The essential nature of artistic activity has changed fundamentally, progressing from representation of the spirit of things to conscious action. —Varvara Stepanova, c. 1921 1 Art must not be a manifestation of the artist’s individualism, but the result of an effort by the collective in which the artist is the worker and inventor. —Editors of Blok, 1924 2 My mouth, the working class’s megaphone. —Vladimir Mayakovsky, 1926 3 There has never been so much paper printed as today, the painter and draftsman have never had the opportunity to collaborate with print/the press as today. Through print they work for life. —Ladislav Sutnar, 1938 4 1. Varvara Stepanova, “On Constructivism” (fragmentary notes for a paper to be given at INKhUK on December 22, 1921), in Art into Life: Russian Constructivism, 1914–1932; trans. James West (Seattle and New York: Henry Art Gallery; Rizzoli, 1990), p. 74. 2. Editorial statement, Blok, no. 1 (March 8, 1924), in Between Worlds: A Sourcebook of Central European Avant-Gardes, ed. Timothy O. Benson and Éva Forgács, trans. Wanda Kemp-Welch (Los Angeles and Cambridge, MA: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; MIT Press, 2002), p. 491. 3. Vladimir Mayakovsky, “Razgovor s fininspectorom o poezii” (1926); trans. Katie Farris and Ilya Kaminsky as “Conversation with a Tax Collector about Poetry”; see p. 74 of this volume. 4. Ladislav Sutnar, “Poslání výtvarného umělce v reklamě,” in Umění do reklamy (Prague: Novina, 1938), p. -

Lever Handles 4A Aluminium 68

Lever handles 4a Aluminium 68 AluGrey 70 Alu + color 71 Stainless steel 72 Overview 74 Product families 76 67 Aluminium Aluminium is the most com- After machining, the surface is 2. Deep staining of the Aluminium essentially needs mon metal in the Earth’s crust anodised. This is an electro- oxidised coating no looking after. The surface (8 %). It occurs widely in feld- chemical process which trans- is protected by natural or arti- spar, mica, and clay materials forms the surface of the metal Metals and metal compounds ficial anodisation. Marks can and is mainly extracted from into a given thickness of alu- are electrolytically implanted be removed with water and a bauxite. minium oxide. into the silvery oxidised layer soft cloth. Aluminium is a light metal FSB uses the standard GS using an alternating current. Harder materials can gouge (relative density 2.699 g/cu.m) process to form its anodised This is also known as the two- or abrade an aluminium surface. with a melting point of 660 de- coatings. GS are the German step method. Non-fade factors The scratches l.h. by rings are grees Celsius. Its natural co- initials for direct-current range between 7 and 8. a typical example. Though lour is silvery white. It can be sulphuric acid electrolysis, such blemishes may be a visu- cast or rolled into virtually any which produces an oxidised al nuisance, they in no way shape, including foil. layer approx. 10 μm thick. impair the functional proper- Aluminium is extracted from Coating hardness is between ties of the product. -

New Ways of Seeing: the Photography of the 1920S and ‘30S

WALL AND LABEL TEXTS NEW WAYS OF SEEING: THE PHOTOGRAPHY OF THE 1920S AND ‘30S 30 JUNE TO 24 OCTOBER 2021 GERMAN PHOTOGRAPHIC EXHIBITION, FRANKFURT AM MAIN The German Photographic Exhibition was the first post-World-War-I photography exhibition. Staged at the Haus der Moden in Frankfurt am Main in 1926, it covered the entire spectrum of the medium from professional, scientific, and historical photography to the photo industry and specialist literature. The show played a key role in smoothing the way for a new perception of photography, not only among contemporary experts, but virtually throughout society. The result was to anchor the medium firmly in everyday life. Numerous exhibitions and fairs in subsequent years further solidified photography’s position. At the same time, photographers began publishing their works in specially compiled books. A case in point is Albert Renger- Patzsch’s The World Is Beautiful (1928). Publications of this kind were hugely popular at the time and today possess scarcity value. TRAINING It was in the 1920s that photography was introduced as a teaching subject at art academies and private educational establishments. This led to the development of professional standards and a redefinition of the role of the photographer. The schools were organized in different ways. The more conservative ones took the crafts as their orientation (Teaching and Research Institute for Photography, Munich; Lette Society, Berlin), others adopted an approach that can be referred to as documentary in the broadest sense (Giebichenstein Castle, Halle), and still others pursued the experimental application of photography in advertising graphics (Folkwang School, Essen).