African Miracle Or a Case of Mistaken Identity?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ÿþm I C R O S O F T W O R

E WL E WL REGISTERED WITH THE DIRECTOR OF POSTS AND TELEGRAPHS AS A NEWSPAPER Volume V No. 7 Organ of the Botswana Democratic Party JULY, 1967. LOETO LA TONA YA 'TEMO MO dikgweding tse di fitileng Tona ya Temo, Morena Tsheko T~sheko o ne a tsamaya thata mo mafelong a mantsi a Botswana, go bona balemi le barua-kgomo le go bona ditiro tsa ba Lephata la Temo le ba Lephata la Leruo. Mo mafelong otihe o ne a ntse a buisanya le babusi le magosi le merafe mo kgotleng le balemi ba basweu le ba bantsho. Me go itumedisa thata go bolela gore mo mafelong otlhe a a a tsamaileng pula e nele sentle mabele a teng le phulo e ntsi. Tota mo mafelong a mangwe pula e nele go feta selekanyo mo ebileng e ntshofaditse mabele ya bodisa dinawa le dithotse. Puo e o neng a e bua le batho bogolo e ne e le ya go ba kgothatsa go lema thata go katolosa masimo le go a epa disana le gore batho ba dire mo masimong a bone ngwaga otlhe eseng go ntsha dijo mo masismo go tswa foo batho ba bo ba siela kwa magaeng a matona goya go nna ba sa dire sepe. 0 ne a tlhalosa ka gore Goromente o lemoga gore temo le leruo mo Bot.swana ke tsone tse di tshetsang batho ka go sena mekoti le ditiro. Me a bolela ka gore Goromente o aga sekwele se segolo kwa Gaborone se se tla rutang makau a Botswana temo le tlhokomelo ya leruo gore ba gasiwe le lefatshe la Botswana go ruta batho ka bontsi go lema mo go tla ba tswelang molemo. -

Populated Printable COP 2009 Botswana Generated 9/28/2009 12:01:26 AM

Populated Printable COP 2009 Botswana Generated 9/28/2009 12:01:26 AM ***pages: 415*** Botswana Page 1 Table 1: Overview Executive Summary None uploaded. Country Program Strategic Overview Will you be submitting changes to your country's 5-Year Strategy this year? If so, please briefly describe the changes you will be submitting. X Yes No Description: test Ambassador Letter File Name Content Type Date Uploaded Description Uploaded By Letter from Ambassador application/pdf 11/14/2008 TSukalac Nolan.pdf Country Contacts Contact Type First Name Last Name Title Email PEPFAR Coordinator Thierry Roels Associate Director GAP-Botswana [email protected] DOD In-Country Contact Chris Wyatt Chief, Office of Security [email protected] Cooperation HHS/CDC In-Country Contact Thierry Roels Associate Director GAP-Botswana [email protected] Peace Corps In-Country Peggy McClure Director [email protected] Contact USAID In-Country Contact Joan LaRosa USAID Director [email protected] U.S. Embassy In-Country Phillip Druin DCM [email protected] Contact Global Fund In-Country Batho C Molomo Coordinator of NACA [email protected] Representative Global Fund What is the planned funding for Global Fund Technical Assistance in FY 2009? $0 Does the USG assist GFATM proposal writing? Yes Does the USG participate on the CCM? Yes Generated 9/28/2009 12:01:26 AM ***pages: 415*** Botswana Page 2 Table 2: Prevention, Care, and Treatment Targets 2.1 Targets for Reporting Period Ending September 30, 2009 National 2-7-10 USG USG Upstream USG Total Target Downstream (Indirect) -

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization. Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Ijagbemi, Bayo, 1963- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 17:13:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/196133 LAND TENURE REFORMS AND SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION IN BOTSWANA: IMPLICATIONS FOR URBANIZATION by Bayo Ijagbemi ____________________ Copyright © Bayo Ijagbemi 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2006 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Bayo Ijagbemi entitled “Land Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Thomas Park _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Stephen Lansing _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr David Killick _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Mamadou Baro Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Botswana Semiology Research Centre Project Seismic Stations In

BOTSWANA SEISMOLOGICAL NETWORK ( BSN) STATIONS 19°0'0"E 20°0'0"E 21°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 23°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 1 S 7 " ° 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° " 7 S 1 KSANE Kasane ! !Kazungula Kasane Forest ReserveLeshomo 1 S Ngoma Bridge ! 8 " ! ° 0 0 ' # !Mabele * . MasuzweSatau ! ! ' 0 ! ! Litaba 0 ° Liamb!ezi Xamshiko Musukub!ili Ivuvwe " 8 ! ! ! !Seriba Kasane Forest Reserve Extension S 1 !Shishikola Siabisso ! ! Ka!taba Safari Camp ! Kachikau ! ! ! ! ! ! Chobe Forest Reserve ! !! ! Karee ! ! ! ! ! Safari Camp Dibejam!a ! ! !! ! ! ! ! X!!AUD! M Kazuma Forest Reserve ! ShongoshongoDugamchaRwelyeHau!xa Marunga Xhauga Safari Camp ! !SLIND Chobe National Park ! Kudixama Diniva Xumoxu Xanekwa Savute ! Mah!orameno! ! ! ! Safari Camp ! Maikaelelo Foreset Reserve Do!betsha ! ! Dibebe Tjiponga Ncamaser!e Hamandozi ! Quecha ! Duma BTLPN ! #Kwiima XanekobaSepupa Khw!a CHOBE DISTRICT *! !! ! Manga !! Mampi ! ! ! Kangara # ! * Gunitsuga!Njova Wazemi ! ! G!unitsuga ! Wazemi !Seronga! !Kaborothoa ! 1 S Sibuyu Forest Reserve 9 " Njou # ° 0 * ! 0 ' !Nxaunxau Esha 12 ' 0 Zara ! ! 0 ° ! ! ! " 9 ! S 1 ! Mababe Quru!be ! ! Esha 1GMARE Xorotsaa ! Gumare ! ! Thale CheracherahaQNGWA ! ! GcangwaKaruwe Danega ! ! Gqose ! DobeQabi *# ! ! ! ! Bate !Mahito Qubi !Mahopa ! Nokaneng # ! Mochabana Shukumukwa * ! ! Nxabe NGAMILAND DISTRICT Sorob!e ! XurueeHabu Sakapane Nxai National Nark !! ! Sepako Caecae 2 ! ! S 0 " Konde Ncwima ° 0 ! MAUN 0 ' ! ! ' 0 Ntabi Tshokatshaa ! 0 ° ! " 0 PHDHD Maposa Mmanxotai S Kaore ! ! Maitengwe 2 ! Tsau Segoro -

2011 Population & Housing Census Preliminary Results Brief

2011 Population & Housing Census Preliminary Results Brief For further details contact Census Office, Private Bag 0024 Gaborone: Tel 3188500; Fax 3188610 1. Botswana Population at 2 Million Botswana’s population has reached the 2 million mark. Preliminary results show that there were 2 038 228 persons enumerated in Botswana during the 2011 Population and Housing Census, compared with 1 680 863 enumerated in 2001. Suffice to note that this is the de-facto population – persons enumerated where they were found during enumeration. 2. General Comments on the Results 2.1 Population Growth The annual population growth rate 1 between 2001 and 2011 is 1.9 percent. This gives further evidence to the effect that Botswana’s population continues to increase at diminishing growth rates. Suffice to note that inter-census annual population growth rates for decennial censuses held from 1971 to 2001 were 4.6, 3.5 and 2.4 percent respectively. A close analysis of the results shows that it has taken 28 years for Botswana’s population to increase by one million. At the current rate and furthermore, with the current conditions 2 prevailing, it would take 23 years for the population to increase by another million - to reach 3 million. Marked differences are visible in district population annual growths, with estimated zero 3 growth for Selebi-Phikwe and Lobatse and a rate of over 4 percent per annum for South East District. Most district growth rates hover around 2 percent per annum. High growth rates in Kweneng and South East Districts have been observed, due largely to very high growth rates of villages within the proximity of Gaborone. -

Botswana. Supervisor of Elections. . Report to the Minister of State on the General Elections, 1974

Botswana. Supervisor of Elections. Report to the Minister of State on the general elections, 1974. Gaborone, Government Printer [1974?] / 30p. 29cm. 1. Botswana-Pol. & govt. 2. Elections- Botswana. I • INDEX Page. Report to the Minister of State on the General Elections, 1974 Evaluation and Recommendations *"* Conclusion ...... 2 - • • • • 4 Title Appendix lA' A list of Constituencies, Polling Districts and Polling Stations showing the number of registered voters by constituency and polling station Appendix '/?' Authenticating Officers appointed in accordance with the Presidential Elections (Supplementary Provisions) Act >;• 12 Appendix 'C A list of Returning Officers for the Parliamentary Elections • ! l 13 Appendix Z)' A list of Returning Officers for the Local Government Elections .. ^ . 14 Appendix 'ZT Summary of the Parliamentary election results Appendix lF 17 A list of candidates in the Parliamentary Election showing the number of votes cast for each, number of votes in each constituency, and the majority gained by the winning can- didate and the percentage poll 18 Appendix '6" Summary of Local Government Election results by District or Town Council 20 Appendix 'IT A list of candidates in the Local Government election showing the number of votes cast tor each, the number of voters in each Polling District, the majority gained by the win- ning candidate, and the percentage poll / 22 Appendix T A list of political Parries registered under Section 149 of the Electoral Act 1969 30 Appendix ' J" A Report on-expenditure on the 1974 General Election 30 Sir, REPORT TO ™E MINISTER. OF STATE ON THE GENERAL ELECTIONS, 1974 SSSITOSSS: S.»=^^HS£s~rr?' Lo^l Government Election* become generally available to the public - - - > »S5S^S^as: • l^^sstsss^aSSSS^5^^-^-"5 5. -

Copyright Government of Botswana CHAPTER 69:04

CHAPTER 69:04 - PUBLIC ROADS: SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION INDEX TO SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION Declaration of Public Roads and Width of Public Roads Order DECLARATION OF PUBLIC ROADS AND WIDTH OF PUBLIC ROADS ORDER (under section 2 ) (11th March, 1960 ) ARRANGEMENT OF PARAGRAPHS PARAGRAPHS 1. Citation 2. Establishment and declaration of public roads 3. Width of road Schedule G.N. 5, 1960, L.N. 84, 1966, G.N. 46, 1971, S.I. 106, 1971, S.I. 94, 1975, S.I. 95, 1975, S.I. 96, 1975, S.I. 97, 1982, S.I. 98, 1982, S.I. 99, 1982, S.I. 100, 1982, S.I. 53, 1983, S.I. 90, 1983, S.I. 6, 1984, S.I. 7, 1984, S.I. 151, 1985, S.I. 152, 1985. 1. Citation This Order may be cited as the Declaration of Public Roads and Width of Public Roads Order. 2. Establishment and declaration of public roads The roads described in the Schedule hereto are established and declared as public roads. 3. Width of road The width of every road described in the Schedule hereto shall be 30,5 metres on either side of the general run of the road. SCHEDULE Description District Distance in kilometres RAMATLABAMA-LOBATSE Southern South 48,9 East Commencing at the Botswana-South Africa border at Ramatlabama and ending at the southern boundary of Lobatse Township as shown on Plan BP225 deposited with the Director of Surveys and Lands, Gaborone. LOBATSE-GABORONE South East 65,50 Copyright Government of Botswana ("MAIN ROAD") Leaving the statutory township boundary of Lobatse on the western side of the railway and entering the remainder of the farm Knockduff No. -

Establishment of Subordinate Land Boards (Amendment) Order

CHAPTER 32:02 - TRIBAL LAND: SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION INDEX TO SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION Establishment of Subordinate Land Boards (Amendment) Order Establishment of Subordinate Land Boards Order Tribal Land (Establishment of Land Tribunals) Order Tribal Land (Subordinate Land Boards) Regulations Tribal Land Regulations ESTABLISHMENT OF SUBORDINATE LAND BOARDS ORDER (under section 19) (15th June, 1973) ARRANGEMENT OF PARAGRAPHS PARAGRAPH 1. Citation 2. Establishment 3. Area of jurisdiction 4. Functions Schedule S.I. 47, 1973, S.I. 3, 1979, S.I. 125, 1979, S.I. 132, 1980, S.I. 78, 1981, S.I. 81, 1981, S.I. 110, 1981, S.I. 68, 1982, S.I. 5, 1984, S.I. 92, 1984, S.I. 36, 1986, S.I. 55,1987, S.I. 97, 1989, S.I. 45, 1992, S.I. 66, 1994, S.I. 53, 2002. 1. Citation Copyright Government of Botswana This Order may be cited as the Establishment of Subordinate Land Boards Order. 2. Establishment The subordinate land boards referred to in the second column of the Schedule hereto are established as the subordinate land boards within the district named in the first column of the said Schedule. 3. Area of jurisdiction The area of jurisdiction in respect of which each subordinate Land Board will perform its functions shall be the area or villages stated in relation to each subordinate land board in the third column of the Schedule. 4. Functions (1) The functions under customary law which vest in the subordinate land authority which are transferred to the subordinate land board shall include the hearing, grant or refusal of applications to use land for— ( a) building residences or extensions thereto; ( b) ploughing to a maximum extent of land determined by the tribal land board; ( c) grazing cattle or other stock; ( d) communal uses in the village. -

Ministry of Health Republic of Botswana World Health Organization

Ministry of Health Republic of Botswana World Health Organization Botswana STEPS survey Chronic Disease Risk Factor Surveillance 2007 Figure 1 Map of Botswana Ministry of Health, DPH, Disease Control Division - Private Bag 00269, Fax 267 3910327, Tel 2673622500 Page 2 Botswana STEPS survey Chronic Disease Risk Factor Surveillance 2007 ABSTRACT Botswana as a developing country is experiencing the emergence of non-communicable diseases which will impact on its development. If risk factors leading to chronic diseases are not identified and sustainable measures are not put in place it can have far reaching consequences. Therefore there is a need to establish baseline data on risk factors, develop guidelines, lay strategic plans and appropriate public health measures in the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. This necessitated embarking the STEPS survey of chronic diseases risk factors. Using the WHO STEPwise approach to surveillance, Botswana carried out STEP 1, which deals with demographic and behavioural aspects, and STEP 2, which deals with physical measurement of height, weight, waist and hip; blood pressure, and pulse rate. The survey was conducted from March to May 2007 in collaboration with the Ministry of Local Government in 8 selected districts. The Botswana STEPS survey was a population based survey of adults aged 25-64. A multi-stage cluster sample design was used to arrive at a representative sample for the whole population. The response rate was very high and a total of 4003 people participated in the survey. The major risk factors associated with non-communicable diseases that we included in the survey were tobacco, alcohol, eating fruits and vegetables, physical activity, blood pressure and BMI. -

Public Primary Schools

PRIMARY SCHOOLS CENTRAL REGION NO SCHOOL ADDRESS LOCATION TELE PHONE REGION 1 Agosi Box 378 Bobonong 2619596 Central 2 Baipidi Box 315 Maun Makalamabedi 6868016 Central 3 Bobonong Box 48 Bobonong 2619207 Central 4 Boipuso Box 124 Palapye 4620280 Central 5 Boitshoko Bag 002B Selibe Phikwe 2600345 Central 6 Boitumelo Bag 11286 Selibe Phikwe 2600004 Central 7 Bonwapitse Box 912 Mahalapye Bonwapitse 4740037 Central 8 Borakanelo Box 168 Maunatlala 4917344 Central 9 Borolong Box 10014 Tatitown Borolong 2410060 Central 10 Borotsi Box 136 Bobonong 2619208 Central 11 Boswelakgomo Bag 0058 Selibe Phikwe 2600346 Central 12 Botshabelo Bag 001B Selibe Phikwe 2600003 Central 13 Busang I Memorial Box 47 Tsetsebye 2616144 Central 14 Chadibe Box 7 Sefhare 4640224 Central 15 Chakaloba Bag 23 Palapye 4928405 Central 16 Changate Box 77 Nkange Changate Central 17 Dagwi Box 30 Maitengwe Dagwi Central 18 Diloro Box 144 Maokatumo Diloro 4958438 Central 19 Dimajwe Box 30M Dimajwe Central 20 Dinokwane Bag RS 3 Serowe 4631473 Central 21 Dovedale Bag 5 Mahalapye Dovedale Central 22 Dukwi Box 473 Francistown Dukwi 2981258 Central 23 Etsile Majashango Box 170 Rakops Tsienyane 2975155 Central 24 Flowertown Box 14 Mahalapye 4611234 Central 25 Foley Itireleng Box 161 Tonota Foley Central 26 Frederick Maherero Box 269 Mahalapye 4610438 Central 27 Gasebalwe Box 79 Gweta 6212385 Central 28 Gobojango Box 15 Kobojango 2645346 Central 29 Gojwane Box 11 Serule Gojwane Central 30 Goo - Sekgweng Bag 29 Palapye Goo-Sekgweng 4918380 Central 31 Goo-Tau Bag 84 Palapye Goo - Tau 4950117 -

2013/2014 Kweneng East District Evidence Based Plan

2013/2014 Kweneng East District Evidence Based Plan Submitted: 10‐Dec‐2012 District AIDS Coordinating Office Molepolole Ms. Theresa N. Makati, DAC Mr. K. Ntshese, M&E Mr. P. Reetsang, BNAPS Grant Coordinator Ms. Patlo Entaile, BNAPS Grant Coordinator [email protected] Page 1 of 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 Community Services Inventory 4 District HIV/AIDS Profile 5 DMSAC Plan for 2010‐2011 7 Final Summary 8 Appendix A ‐ CSI Alphabetic Full Listing Appendix B ‐ CSI Target Group Listing Appendix C ‐ CSI Type of Activity Offered Listing Appendix D ‐ CSI Type of Service Offered Listing Appendix E ‐ Plan Activities and Budget Page 2 of 7 Executive Summary Kweneng East District has more than 117 organizations in the district that help provide HIV/AIDS‐ related services as well as 19 ARV sites. These include 2 Hospitals and 42 Health Facilities which are made up of Clinics, Health Posts and Testing Sites. The theme for 2011 through 2016 is “Getting to Zero”. This means zero new infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS related deaths. To facilitate the success of this theme, the Kweneng East DMSAC recently completed its Evidence Based Planning (EBP) process for financial year 2013‐2014. This process involved forming a Planning Group consisting of DMSAC/TAC members, AIDS service organizations representatives, PLWHAs, and traditional leaders in the district. The planning process began by researching and writing an HIV/AIDS profile for the district, the District Profile, and updating the HIV/AIDS Community Services Inventory (CSI). The Planning Group held a one week EBP Training Workshop where collectively they reviewed the District Profile and establish a prioritized list of key issues as follows: 1) Low HIV Testing 2) Low SMC Uptake 3) Low Screening of HIV+ Clients for TB 4) High STI Incidence 5) High Teenage Pregnancy For each issue the Planning Group drafted SMART objectives to guide the creation of strategies to address these issues, which are listed in priority order under each objective. -

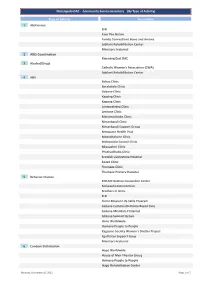

By Type of Activity)

Molelepolo DAC ‐ Community Service Inventory (By Type of Activity) Type of Activity Association 1 Abstinence EFB Face The Nation Family Connections Bows and Arrows Jubilant Rehabilitation Center Ministers Fraternal 2 AIDS Coordination Kweneng East DAC 3 Alcohol/Drugs Catholic Women's Association (CWA) Jubilant Rehabilitation Center 4 ARV Bokaa Clinic Borakalalo Clinic Gabane Clinic Kgosing Clinic Kopong Clinic Lentsweletau Clinic Lesirane Clinic Metsimotlhabe Clinic Mmankgodi Clinic Mmankgodi Support Group Mmopane Health Post Mogoditshane Clinic Molepolole Council Clinic Nkoyaphiri Clinic Phuthadikobo Clinic Scottish Livingstone Hospital Sojwe Clinic Thamaga Clinic Thamaga Primary Hospital 5 Behavior Change BOCAIP‐Keletso Counseling Center Boikgapho Intervention Brothers in Arms EFB Flying Mission Life Skills Program Gabane Community Home Based Care Gabane Ministers Fraternal Gabane Support Group Hope Worldwide Humana People to People Kagisano Society Women's Shelter Project Kgothatso Support Goup Ministers Fraternal 6 Condom Distribution Hope Worldwide House of Men Theater Group Humana People to People Ikago Rehabilitation Center Monday, December 10, 2012 Page 1 of 5 Molelepolo DAC ‐ Community Service Inventory (By Type of Activity) Type of Activity Association Kweneng Deputy District Commissioner Lekgwapeng Health Post Molepolole Administration of Justice Molepolole College Clinic Molepolole Education Centre Molepolole Institute of Health Sciences (IHS) Police No. 11 District Station Officer Scottish Livingstone Hospital 7 Councelling