Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Working Paper CBMS-2020-09

working paper CBMS-2020-09 Sustainable Development Goals, Botswana: A Case Study of Gabane Village in Kweneng District Happy Siphambe Malebogo Bakwena Lexi Setlhare Mavis Kolobe Itumeleng Oageng Keamogetse Setlhare Tshegofatso Motswagae May 2020 Sustainable Development Goals, Botswana: A Case Study of Gabane Village in Kweneng District Abstract The main objective of the research paper was to use the Community Based Monitoring System (CBMS) methodology to determine progress on achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with a view of localising SDGs to Gabane village. Generally, the results reveal that poverty is prevalent amongst women, youth and children. Specifically, the working poor constitute 40.8% of the people leaving below the poverty line. Noteworthy, is that 50% of children under 5 years of age have no access to pre-primary education. Gabane residents are reluctant to participate in poverty-targeted government programmes as evidenced by a low participation rate. Last but not least, the results show a higher unemployment rate of 23.3 %( ILO or narrow definition) and 29.44% (broad definition) in Gabane. The majority of the unemployed were youth and women. The policy implications of the results are that the government of Botswana should review the current minimum wage legislation to ensure that the minimum wage is aligned to the cost of living so as to ensure decent wages. Finally, in order to ensure that early childhood is rolled out for all under 5s, the government should expedite the implementation of the Education and Training Strategy Sector Plan (ETSSP) of 2015-2020. JEL: I32, I33, J88 Keywords: Poverty analysis, poverty, welfare and wellbeing. -

Daily Hansard 08 March 2017

DAILY YOUR VOICE IN PARLIAMENT THE SECOND MEETING OF THE THIRD SESSION OF THE ELEVENTH PARLIAMENT WEDNESDAY 08 MARCH 2017 MIXED VERSION HANSARD NO. 187 DISCLAIMER Unocial Hansard This transcript of Parliamentary proceedings is an unocial version of the Hansard and may contain inaccuracies. It is hereby published for general purposes only. The nal edited version of the Hansard will be published when available and can be obtained from the Assistant Clerk (Editorial). THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SPEAKER The Hon. Gladys K. T. Kokorwe MP. DEPUTY SPEAKER The Hon. Kagiso P. Molatlhegi, MP Gaborone South Clerk of the National Assembly - Ms B. N. Dithapo Deputy Clerk of the National Assembly - Ms T. Tsiang Learned Parliamentary Counsel - Mr S. Chikanda Assistant Clerk (E) - Mr R. Josiah CABINET His Excellency Lt. Gen. Dr. S. K. I. Khama PH, FOM, - President DCO, DSM, MP. His Honour M. E. K. Masisi, MP. (Moshupa- Vice President Manyana) - Hon. Dr. P. Venson-Moitoi, MP. (Serowe South) - Minister of International Affairs and Cooperation Hon. S. Tsogwane, MP. (Boteti North) - Minister of Local Government and Rural Development Hon. N. E. Molefhi, MP. (Selebi Phikwe East) - Minister of Infrastructure and Housing Development Hon. S. Kgathi, MP. (Bobirwa) - Minister of Defence, Justice and Security Hon. O. K. Mokaila, MP. (Specially Elected) - Minister of Transport and Communications Hon. P. M. Maele, MP. (Lerala - Maunatlala) - Minister of Land Management, Water and Sanitation Services Hon. E. J. Batshu, MP. (Nkange) - Minister of Nationality, Immigration and Gender Affairs Hon. D. K. Makgato, MP. (Sefhare - Ramokgonami) - Minister of Health and Wellness Minister of Environment, Natural Resources Conservation and Hon. -

Malejane Unpublished (MSW) 2017

Faculty of Social Sciences School of Graduate Studies Department of Social Work Masters of social work (Social Policy and Administration) Topic: Assessing the Perceptions of the Beneficiaries of the Presidential Housing Appeal in Botswana: A Case Study of Gabane Village By; Mr Aobakwe Bacos Malejane ID Number; 201103575 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of a Master’s Degree in Social Work (Social Policy and Administration) Assessing the Perceptions of the Beneficiaries of the Presidential Housing Appeal in Botswana: A Case Study of Gabane Village By Mr Aobakwe Bacos Malejane Student Number; 201103575 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of a Master’s Degree in Social Work (Social Policy and Administration) SUPERVISED BY; Dr. O. Jankey Prof. L.K. Mwansa STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY This dissertation was undertaken from August 2016 to May 2017. The contents of the dissertation are the original work of the student except where reference have been made. __________________________ _________________________ Student’s signature Date DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to Mr. Mahia Ooke, Mrs. Gakedumele Tshimong Ooke, Mr. Thomas Malejane and Mrs. Ntlhabololang Malejane who are a true inspiration in my quest of being a humanitarian through their selfless and compassion in promotion of lives of those less fortunate in remote areas. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For this master piece to be complete, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my research supervisor Dr. O. Jankey and Prof. L. K. Mwansa for the continuous support of my master’s degree study and research, for their patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and immense knowledge. -

2017 SEAT Report Jwaneng Mine

JWANENG MINE SEAT 3REPORT 2017 - 2020 Contents INTRODUCTION TO JWANENG MINE’S SEAT 14 EXISTING SOCIAL PERFORMANCE 40 1. PROCESS 4. MANAGEMENT ACTIVITIES 1.1. Background and Objectives 14 4.1. Debswana’s Approach to Social Performance 41 and Corporate Social Investment 1.2. Approach 15 4.1.1. Approach to Social Performance 41 1.3. Stakeholders Consulted During SEAT 2017 16 4.1.2. Approach to CSI Programmes 41 1.4. Structure of the SEAT Report 19 4.2. Mechanisms to Manage Social Performance 41 2. PROFILE OF JWANENG MINE 20 4.3. Ongoing Stakeholder Engagement towards 46 C2.1. Overview of Debswana’s Operational Context 20 Social Performance Management 2.2. Overview of Jwaneng Mine 22 DELIVERING SOCIO-ECONOMIC BENEFIT 49 2.2.1. Human Resources 23 5. THROUGH ALL MINING ACTIVITIES 2.2.2. Procurement 23 5.1. Overview 50 2.2.3. Safety and Security 24 5.2. Assessment of Four CSI/SED Projects 52 2.2.4. Health 24 5.2.1. The Partnership Between Jwaneng Mine 53 Hospital and Local Government 2.2.5. Education 24 5.2.2. Diamond Dream Academic Awards 54 2.2.6. Environment 25 5.2.3. Lefhoko Diamond Village Housing 55 2.3. Future Capital Investments and Expansion 25 Plans 5.2.4. The Provision of Water to Jwaneng Township 55 and Sese Village 2.3.1. Cut-8 Project 25 5.3. Assessing Jwaneng Mine’s SED and CSI 56 2.3.2. Cut-9 Project 25 Activities 2.3.3. The Jwaneng Resource Extension Project 25 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS 58 (JREP) 6. -

Botswana Environment Statistics Water Digest 2018

Botswana Environment Statistics Water Digest 2018 Private Bag 0024 Gaborone TOLL FREE NUMBER: 0800600200 Tel: ( +267) 367 1300 Fax: ( +267) 395 2201 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.statsbots.org.bw Published by STATISTICS BOTSWANA Private Bag 0024, Gaborone Phone: 3671300 Fax: 3952201 Email: [email protected] Website: www.statsbots.org.bw Contact Unit: Environment Statistics Unit Phone: 367 1300 ISBN: 978-99968-482-3-0 (e-book) Copyright © Statistics Botswana 2020 No part of this information shall be reproduced, stored in a Retrieval system, or even transmitted in any form or by any means, whether electronically, mechanically, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Statistics Botswana. BOTSWANA ENVIRONMENT STATISTICS WATER DIGEST 2018 Statistics Botswana PREFACE This is Statistics Botswana’s annual Botswana Environment Statistics: Water Digest. It is the first solely water statistics annual digest. This Digest will provide data for use by decision-makers in water management and development and provide tools for the monitoring of trends in water statistics. The indicators in this report cover data on dam levels, water production, billed water consumption, non-revenue water, and water supplied to mines. It is envisaged that coverage of indicators will be expanded as more data becomes available. International standards and guidelines were followed in the compilation of this report. The United Nations Framework for the Development of Environment Statistics (UNFDES) and the United Nations International Recommendations for Water Statistics were particularly useful guidelines. The data collected herein will feed into the UN System of Environmental Economic Accounting (SEEA) for water and hence facilitate an informed management of water resources. -

Migrant Labour in the Bukalanga Area, 1934-1985: the Unfinished Story

Historia, 63, 1, May 2018, pp 130-149 Skills acquisition and investments by Batswana migrants from southern Botswana to South Africa, 1970–2010 Wazha G. Morapedi* Abstract This paper focuses on migrant labour from southern Botswana to South Africa. The main thrust of this article is its emphasis on the positive contribution of migration to the migrants and their communities. It is argued here that although migrant labour has been blamed for having negative socio-economic effects in southern Botswana, just as in other parts of the country, it also contributed, and continues to contribute positively to the wellbeing of some households and their communities at large. Through the use of case studies from different villages in the district, the article demonstrates that poor, uneducated and unskilled young men who migrated to South Africa managed to accumulate and invest in agriculture and commercial enterprises and rose up the social ladder. In this area, migrant wages were critical in forming the basis of some enterprises, several of which are still flourishing. It also argues that some migrants acquired on-the-job skills which were later utilised productively when the migrants returned to Botswana. A similar study, but one which did not emphasise the acquisition of skills was undertaken by the author in the Bukalanga region of north-eastern Botswana in 2004. Key Words: Botswana; South Africa; migration; agriculture; labourers. Opsomming Hierdie artikel fokus op trekarbeid van suidelike Botswana na Suid-Afrika. Die artikel poog om die positiewe bydrae wat migrasie vir migrante en hul gemeenskappe inhou, te beklemtoon. Ten spyte daarvan dat trekarbeid vir verskeie negatiewe sosio- ekonomiese uitwerkings in Botswana blameer is, word hier geargumenteer dat trekarbeid positief bydrae tot die welstand van sekere huishoudings en gemeenskappe in die breë. -

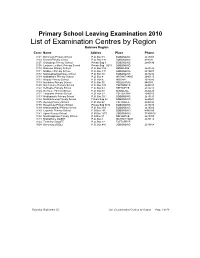

List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O

Primary School Leaving Examination 2010 List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O. Box 48 BOBONONG 2619207 0103 Borotsi Primary School P.O. Box 136 BOBONONG 819208 0107 Gobojango Primary School Private Bag 8 BOBONONG 2645436 0108 Lentswe-Le-Moriti Primary School Private Bag 0019 BOBONONG 0110 Mabolwe Primary School P.O. Box 182 SEMOLALE 2645422 0111 Madikwe Primary School P.O. Box 131 BOBONONG 2619221 0112 Mafetsakgang primary school P.O. Box 46 BOBONONG 2619232 0114 Mathathane Primary School P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0117 Mogapi Primary School P.O. Box 6 MOGAPI 2618545 0119 Molalatau Primary School P.O. Box 50 MOLALATAU 845374 0120 Moletemane Primary School P.O. Box 176 TSETSEBYE 2646035 0123 Sefhophe Primary School P.O. Box 41 SEFHOPHE 2618210 0124 Semolale Primary School P.O. Box 10 SEMOLALE 2645422 0131 Tsetsejwe Primary School P.O. Box 33 TSETSEJWE 2646103 0133 Modisaotsile Primary School P.O. Box 591 BOBONONG 2619123 0134 Motlhabaneng Primary School Private Bag 20 BOBONONG 2645541 0135 Busang Primary School P.O. Box 47 TSETSEBJE 2646144 0138 Rasetimela Primary School Private Bag 0014 BOBONONG 2619485 0139 Mabumahibidu Primary School P.O. Box 168 BOBONONG 2619040 0140 Lepokole Primary School P O Box 148 BOBONONG 4900035 0141 Agosi Primary School P O Box 1673 BOBONONG 71868614 0142 Motsholapheko Primary School P O Box 37 SEFHOPHE 2618305 0143 Mathathane DOSET P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0144 Tsetsebye DOSET P.O. Box 33 TSETSEBYE 3024 Bobonong DOSET P.O. Box 483 BOBONONG 2619164 Saturday, September 25, List of Examination Centres by Region Page 1 of 39 Boteti Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0201 Adult Education Private Bag 1 ORAPA 0202 Baipidi Primary School P.O. -

The Republic of Botswana Second and Third Report To

THE REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA SECOND AND THIRD REPORT TO THE AFRICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES' RIGHTS (ACHPR) IMPLEMENTATION OF THE AFRICAN CHARTER ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES’ RIGHTS 2015 1 | P a g e TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PART I. a. Abbreviations b. Introduction c. Methodology and Consultation Process II. PART II. A. General Information - B. Laws, policies and (institutional) mechanisms for human rights C. Follow-up to the 2010 Concluding observations D. Obstacles to the exercise and enjoyment of the rights and liberties enshrined in the African Charter: III. PART III A. Areas where Botswana has made significant progress in the realization of the rights and liberties enshrined in the African Charter a. Article 2, 3 and 19 (Non-discrimination and Equality) b. Article 7 & 26 (Fair trial, Independence of the Judiciary) c. Article 10 (Right to association) d. Article 14 (Property) e. Article 16 (Health) f. Article 17 (Education) g. Article 24 (Environment) B. Areas where some progress has been made by Botswana in the realization of the rights and liberties enshrined in the African Charter a. Article 1er (implementation of the provisions of the African Charter) b. Article 4 (Life and Integrity of the person) c. Article 5 (Human dignity/Torture) d. Article 9 (Freedom of Information) e. Article 11 (Freedom of Assembly) f. Article 12 (Freedom of movement) g. Article 13 (participation to public affairs) h. Article 15 (Work) i. Article 18 (Family) j. Article 20 (Right to existence) k. Article 21 (Right to freely dispose of wealth and natural resources) 2 | P a g e C. -

Refundable Fee of P280.00 (Two Hundred and Eighty Pula Only) VAT Inclusive

PUBLIC TENDER NOTICE TENDER NO: BOCRA/PT/006/2020.2021 SUPPLY, INSTALLATION AND COMMISSIONING OF ICT EQUIPMENT AT TWELVE (12) TRIBAL ADMINISTRATIONS IN KWENENG DISTRICT The Botswana Communications Regulatory Authority (BOCRA or the Authority) hereby invites experienced and reputable companies to tender for the Supply, Installation and Commissioning of ICT Equipment at twelve (12) Tribal Administrations in Kweneng District. The tender is reserved for 100% citizen-owned companies who are registered with the Public Procurement and Asset Disposal Board (PPADB) under the following codes and subcodes; Code 203: Electrical, Electronic, Mechanical and ICT Supplies Subcode 01: Electrical and Electronic Equipment, Spares and Accessories (includes ICT, photographic equipment, and others). Youth owned companies in Botswana shall purchase the ITT at 50% of the purchase price as per Presidential Directive CAB 14 (B)/2015. The Invitation to Tender (ITT) document may be purchased at the BOCRA Head Office by interested companies at a non-refundable fee of P280.00 (Two Hundred and Eighty Pula Only) VAT inclusive. Payment must be made in the form of bank transfer or deposits to the following bank details: Bank Name: First National Bank Botswana Ltd Branch Name: Mall Branch Code: 28-28-67 Account Name: Botswana Communications Regulatory Authority Bank Account No: 62011115088 Swift Code: FIRNBWGX Reference: BTA0001 Tender documents shall be issued upon provision of Proof of Payment (POP). All funds transfer bank charges shall be borne by the bidder. Compulsory -

Judging the Epidemic: a Judicial Handbook on HIV, Human Rights

Judging the epidemic A judicial handbook on HIV, human rights and the law UNAIDS / JC2497E (English original, May 2013) ISBN 978-92-9253-025-9 Copyright © 2013. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). All rights reserved. Publications produced by UNAIDS can be obtained from the UNAIDS Information Production Unit. Reproduction of graphs, charts, maps and partial text is granted for educational, not-for-profit and commercial purposes as long as proper credit is granted to UNAIDS: UNAIDS + year. For photos, credit must appear as: UNAIDS/name of photographer + year. Reproduction permission or translation-related requests—whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution—should be addressed to the Information Production Unit by e-mail at: [email protected]. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNAIDS concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. UNAIDS does not warrant that the information published in this publication is complete and correct and shall not be liable for any damages incurred as a result of its use. Unless otherwise indicated photographs used in this document are used for illustrative purposes only. Unless indicated, any person depicted in the document is a “model”, and use of the photograph does not indicate endorsement by the model of the content of this document nor is there any relation between the model and any of the topics covered in this document. -

A Heritage and Cultural Tourism Destination

MAKING GABORONE A STOP AND NOT A STOP-OVER: A HERITAGE AND CULTURAL TOURISM DESTINATION by Jane Thato Dewah (Student No: 12339556) A Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MAGISTER HEREDITATIS CULTURAEQUE SCIENTIAE (HERITAGE AND CULTURAL STUDIES) (TOURISM) In the Department of Historical and Heritage Studies at the Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria SUPERVISOR: Prof. K.L Harris December 2014 DECLARATION OF AUTHENTICITY I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and has not been submitted previously at any other university for a degree. ............................................... Signature Jane Thato Dewah ................................................ Date ii Abstract The main objective of the study was to identify cultural heritage sites in and around Gaborone which could serve as tourist attractions. Gaborone, the capital city of Botswana, has been neglected in terms of tourism, although it has all the facilities needed to cater for this market. Very little information with regards to tourist attractions around Gaborone is available and therefore this study set out to identify relevant sites and discussed their history, relevance and potential for tourism. It also considers ways in which these sites can be developed in order to attract tourists. Due to its exclusive concentration on wildlife and the wilderness, tourism in Botswana tends to benefit only a few. Moreover, it is mainly concentrated in the north western region of the country, leaving out other parts of the country in terms of the tourism industry. To achieve the main objective of the study, which is to identify sites around the capital city Gaborone and to evaluate if indeed the sites have got the potential to become tourist attractions, three models have been used. -

University of Botswana Patterns and Processes Of

UNIVERSITY OF BOTSWANA FACULTY OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE PATTERNS AND PROCESSES OF FOOD SECURITY IN THE PERI URBAN VILLAGE OF GABANE IN BOTSWANA A Dissertation submitted in Partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the MSc Degree in Environmental Science BY GABARATE TSHEKISO 200703630 Supervisors: Prof E.N Toteng (Main Supervisor) Prof T.D Gwebu (Co-Supervisor) August 2017 APPROVAL This dissertation has been examined and is approved as meeting the required standards for the partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Degree in Environmental Science. Internal Examiner______________________________Date______________________ External Examiner______________________________Date_______________________ Dean of Faculty______________________________Date________________________ i STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY The work contained in this dissertation was carried out by the author at the University of Botswana between August 2013 and August 2017. It is an original work except where due reference is made. It has not been and shall not be submitted for the award of any degree or diploma to any other institution of higher learning. Author‟s Signature___________________________ Date___________________ ii DEDICATION I dedicate this work to the Almighty God who had been my strong tower, pillar of strength and given me protection throughout my studies. I also dedicate this project to my son who is just a blessing and joy to my life. I dedicate this work to all the sons and daughters of my Father‟s house (IHL ministry) who tirelessly and persistently prayed for my success. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Firstly I would like to thank my Heavenly Father for providing me with strength, wisdom and perseverance for completing this dissertation for everything is possible with Him.