BMJ Open Is Committed to Open Peer Review. As Part of This Commitment We Make the Peer Review History of Every Article We Publish Publicly Available

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 SEAT Report Jwaneng Mine

JWANENG MINE SEAT 3REPORT 2017 - 2020 Contents INTRODUCTION TO JWANENG MINE’S SEAT 14 EXISTING SOCIAL PERFORMANCE 40 1. PROCESS 4. MANAGEMENT ACTIVITIES 1.1. Background and Objectives 14 4.1. Debswana’s Approach to Social Performance 41 and Corporate Social Investment 1.2. Approach 15 4.1.1. Approach to Social Performance 41 1.3. Stakeholders Consulted During SEAT 2017 16 4.1.2. Approach to CSI Programmes 41 1.4. Structure of the SEAT Report 19 4.2. Mechanisms to Manage Social Performance 41 2. PROFILE OF JWANENG MINE 20 4.3. Ongoing Stakeholder Engagement towards 46 C2.1. Overview of Debswana’s Operational Context 20 Social Performance Management 2.2. Overview of Jwaneng Mine 22 DELIVERING SOCIO-ECONOMIC BENEFIT 49 2.2.1. Human Resources 23 5. THROUGH ALL MINING ACTIVITIES 2.2.2. Procurement 23 5.1. Overview 50 2.2.3. Safety and Security 24 5.2. Assessment of Four CSI/SED Projects 52 2.2.4. Health 24 5.2.1. The Partnership Between Jwaneng Mine 53 Hospital and Local Government 2.2.5. Education 24 5.2.2. Diamond Dream Academic Awards 54 2.2.6. Environment 25 5.2.3. Lefhoko Diamond Village Housing 55 2.3. Future Capital Investments and Expansion 25 Plans 5.2.4. The Provision of Water to Jwaneng Township 55 and Sese Village 2.3.1. Cut-8 Project 25 5.3. Assessing Jwaneng Mine’s SED and CSI 56 2.3.2. Cut-9 Project 25 Activities 2.3.3. The Jwaneng Resource Extension Project 25 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS 58 (JREP) 6. -

Ÿþm I C R O S O F T W O R

E WL E WL REGISTERED WITH THE DIRECTOR OF POSTS AND TELEGRAPHS AS A NEWSPAPER Volume V No. 7 Organ of the Botswana Democratic Party JULY, 1967. LOETO LA TONA YA 'TEMO MO dikgweding tse di fitileng Tona ya Temo, Morena Tsheko T~sheko o ne a tsamaya thata mo mafelong a mantsi a Botswana, go bona balemi le barua-kgomo le go bona ditiro tsa ba Lephata la Temo le ba Lephata la Leruo. Mo mafelong otihe o ne a ntse a buisanya le babusi le magosi le merafe mo kgotleng le balemi ba basweu le ba bantsho. Me go itumedisa thata go bolela gore mo mafelong otlhe a a a tsamaileng pula e nele sentle mabele a teng le phulo e ntsi. Tota mo mafelong a mangwe pula e nele go feta selekanyo mo ebileng e ntshofaditse mabele ya bodisa dinawa le dithotse. Puo e o neng a e bua le batho bogolo e ne e le ya go ba kgothatsa go lema thata go katolosa masimo le go a epa disana le gore batho ba dire mo masimong a bone ngwaga otlhe eseng go ntsha dijo mo masismo go tswa foo batho ba bo ba siela kwa magaeng a matona goya go nna ba sa dire sepe. 0 ne a tlhalosa ka gore Goromente o lemoga gore temo le leruo mo Bot.swana ke tsone tse di tshetsang batho ka go sena mekoti le ditiro. Me a bolela ka gore Goromente o aga sekwele se segolo kwa Gaborone se se tla rutang makau a Botswana temo le tlhokomelo ya leruo gore ba gasiwe le lefatshe la Botswana go ruta batho ka bontsi go lema mo go tla ba tswelang molemo. -

Populated Printable COP 2009 Botswana Generated 9/28/2009 12:01:26 AM

Populated Printable COP 2009 Botswana Generated 9/28/2009 12:01:26 AM ***pages: 415*** Botswana Page 1 Table 1: Overview Executive Summary None uploaded. Country Program Strategic Overview Will you be submitting changes to your country's 5-Year Strategy this year? If so, please briefly describe the changes you will be submitting. X Yes No Description: test Ambassador Letter File Name Content Type Date Uploaded Description Uploaded By Letter from Ambassador application/pdf 11/14/2008 TSukalac Nolan.pdf Country Contacts Contact Type First Name Last Name Title Email PEPFAR Coordinator Thierry Roels Associate Director GAP-Botswana [email protected] DOD In-Country Contact Chris Wyatt Chief, Office of Security [email protected] Cooperation HHS/CDC In-Country Contact Thierry Roels Associate Director GAP-Botswana [email protected] Peace Corps In-Country Peggy McClure Director [email protected] Contact USAID In-Country Contact Joan LaRosa USAID Director [email protected] U.S. Embassy In-Country Phillip Druin DCM [email protected] Contact Global Fund In-Country Batho C Molomo Coordinator of NACA [email protected] Representative Global Fund What is the planned funding for Global Fund Technical Assistance in FY 2009? $0 Does the USG assist GFATM proposal writing? Yes Does the USG participate on the CCM? Yes Generated 9/28/2009 12:01:26 AM ***pages: 415*** Botswana Page 2 Table 2: Prevention, Care, and Treatment Targets 2.1 Targets for Reporting Period Ending September 30, 2009 National 2-7-10 USG USG Upstream USG Total Target Downstream (Indirect) -

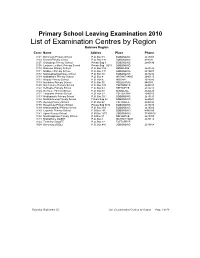

List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O

Primary School Leaving Examination 2010 List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O. Box 48 BOBONONG 2619207 0103 Borotsi Primary School P.O. Box 136 BOBONONG 819208 0107 Gobojango Primary School Private Bag 8 BOBONONG 2645436 0108 Lentswe-Le-Moriti Primary School Private Bag 0019 BOBONONG 0110 Mabolwe Primary School P.O. Box 182 SEMOLALE 2645422 0111 Madikwe Primary School P.O. Box 131 BOBONONG 2619221 0112 Mafetsakgang primary school P.O. Box 46 BOBONONG 2619232 0114 Mathathane Primary School P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0117 Mogapi Primary School P.O. Box 6 MOGAPI 2618545 0119 Molalatau Primary School P.O. Box 50 MOLALATAU 845374 0120 Moletemane Primary School P.O. Box 176 TSETSEBYE 2646035 0123 Sefhophe Primary School P.O. Box 41 SEFHOPHE 2618210 0124 Semolale Primary School P.O. Box 10 SEMOLALE 2645422 0131 Tsetsejwe Primary School P.O. Box 33 TSETSEJWE 2646103 0133 Modisaotsile Primary School P.O. Box 591 BOBONONG 2619123 0134 Motlhabaneng Primary School Private Bag 20 BOBONONG 2645541 0135 Busang Primary School P.O. Box 47 TSETSEBJE 2646144 0138 Rasetimela Primary School Private Bag 0014 BOBONONG 2619485 0139 Mabumahibidu Primary School P.O. Box 168 BOBONONG 2619040 0140 Lepokole Primary School P O Box 148 BOBONONG 4900035 0141 Agosi Primary School P O Box 1673 BOBONONG 71868614 0142 Motsholapheko Primary School P O Box 37 SEFHOPHE 2618305 0143 Mathathane DOSET P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0144 Tsetsebye DOSET P.O. Box 33 TSETSEBYE 3024 Bobonong DOSET P.O. Box 483 BOBONONG 2619164 Saturday, September 25, List of Examination Centres by Region Page 1 of 39 Boteti Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0201 Adult Education Private Bag 1 ORAPA 0202 Baipidi Primary School P.O. -

Refundable Fee of P280.00 (Two Hundred and Eighty Pula Only) VAT Inclusive

PUBLIC TENDER NOTICE TENDER NO: BOCRA/PT/006/2020.2021 SUPPLY, INSTALLATION AND COMMISSIONING OF ICT EQUIPMENT AT TWELVE (12) TRIBAL ADMINISTRATIONS IN KWENENG DISTRICT The Botswana Communications Regulatory Authority (BOCRA or the Authority) hereby invites experienced and reputable companies to tender for the Supply, Installation and Commissioning of ICT Equipment at twelve (12) Tribal Administrations in Kweneng District. The tender is reserved for 100% citizen-owned companies who are registered with the Public Procurement and Asset Disposal Board (PPADB) under the following codes and subcodes; Code 203: Electrical, Electronic, Mechanical and ICT Supplies Subcode 01: Electrical and Electronic Equipment, Spares and Accessories (includes ICT, photographic equipment, and others). Youth owned companies in Botswana shall purchase the ITT at 50% of the purchase price as per Presidential Directive CAB 14 (B)/2015. The Invitation to Tender (ITT) document may be purchased at the BOCRA Head Office by interested companies at a non-refundable fee of P280.00 (Two Hundred and Eighty Pula Only) VAT inclusive. Payment must be made in the form of bank transfer or deposits to the following bank details: Bank Name: First National Bank Botswana Ltd Branch Name: Mall Branch Code: 28-28-67 Account Name: Botswana Communications Regulatory Authority Bank Account No: 62011115088 Swift Code: FIRNBWGX Reference: BTA0001 Tender documents shall be issued upon provision of Proof of Payment (POP). All funds transfer bank charges shall be borne by the bidder. Compulsory -

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization. Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Ijagbemi, Bayo, 1963- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 17:13:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/196133 LAND TENURE REFORMS AND SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION IN BOTSWANA: IMPLICATIONS FOR URBANIZATION by Bayo Ijagbemi ____________________ Copyright © Bayo Ijagbemi 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2006 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Bayo Ijagbemi entitled “Land Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Thomas Park _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Stephen Lansing _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr David Killick _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Mamadou Baro Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Botswana Semiology Research Centre Project Seismic Stations In

BOTSWANA SEISMOLOGICAL NETWORK ( BSN) STATIONS 19°0'0"E 20°0'0"E 21°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 23°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 1 S 7 " ° 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° " 7 S 1 KSANE Kasane ! !Kazungula Kasane Forest ReserveLeshomo 1 S Ngoma Bridge ! 8 " ! ° 0 0 ' # !Mabele * . MasuzweSatau ! ! ' 0 ! ! Litaba 0 ° Liamb!ezi Xamshiko Musukub!ili Ivuvwe " 8 ! ! ! !Seriba Kasane Forest Reserve Extension S 1 !Shishikola Siabisso ! ! Ka!taba Safari Camp ! Kachikau ! ! ! ! ! ! Chobe Forest Reserve ! !! ! Karee ! ! ! ! ! Safari Camp Dibejam!a ! ! !! ! ! ! ! X!!AUD! M Kazuma Forest Reserve ! ShongoshongoDugamchaRwelyeHau!xa Marunga Xhauga Safari Camp ! !SLIND Chobe National Park ! Kudixama Diniva Xumoxu Xanekwa Savute ! Mah!orameno! ! ! ! Safari Camp ! Maikaelelo Foreset Reserve Do!betsha ! ! Dibebe Tjiponga Ncamaser!e Hamandozi ! Quecha ! Duma BTLPN ! #Kwiima XanekobaSepupa Khw!a CHOBE DISTRICT *! !! ! Manga !! Mampi ! ! ! Kangara # ! * Gunitsuga!Njova Wazemi ! ! G!unitsuga ! Wazemi !Seronga! !Kaborothoa ! 1 S Sibuyu Forest Reserve 9 " Njou # ° 0 * ! 0 ' !Nxaunxau Esha 12 ' 0 Zara ! ! 0 ° ! ! ! " 9 ! S 1 ! Mababe Quru!be ! ! Esha 1GMARE Xorotsaa ! Gumare ! ! Thale CheracherahaQNGWA ! ! GcangwaKaruwe Danega ! ! Gqose ! DobeQabi *# ! ! ! ! Bate !Mahito Qubi !Mahopa ! Nokaneng # ! Mochabana Shukumukwa * ! ! Nxabe NGAMILAND DISTRICT Sorob!e ! XurueeHabu Sakapane Nxai National Nark !! ! Sepako Caecae 2 ! ! S 0 " Konde Ncwima ° 0 ! MAUN 0 ' ! ! ' 0 Ntabi Tshokatshaa ! 0 ° ! " 0 PHDHD Maposa Mmanxotai S Kaore ! ! Maitengwe 2 ! Tsau Segoro -

2011 Population & Housing Census Preliminary Results Brief

2011 Population & Housing Census Preliminary Results Brief For further details contact Census Office, Private Bag 0024 Gaborone: Tel 3188500; Fax 3188610 1. Botswana Population at 2 Million Botswana’s population has reached the 2 million mark. Preliminary results show that there were 2 038 228 persons enumerated in Botswana during the 2011 Population and Housing Census, compared with 1 680 863 enumerated in 2001. Suffice to note that this is the de-facto population – persons enumerated where they were found during enumeration. 2. General Comments on the Results 2.1 Population Growth The annual population growth rate 1 between 2001 and 2011 is 1.9 percent. This gives further evidence to the effect that Botswana’s population continues to increase at diminishing growth rates. Suffice to note that inter-census annual population growth rates for decennial censuses held from 1971 to 2001 were 4.6, 3.5 and 2.4 percent respectively. A close analysis of the results shows that it has taken 28 years for Botswana’s population to increase by one million. At the current rate and furthermore, with the current conditions 2 prevailing, it would take 23 years for the population to increase by another million - to reach 3 million. Marked differences are visible in district population annual growths, with estimated zero 3 growth for Selebi-Phikwe and Lobatse and a rate of over 4 percent per annum for South East District. Most district growth rates hover around 2 percent per annum. High growth rates in Kweneng and South East Districts have been observed, due largely to very high growth rates of villages within the proximity of Gaborone. -

E-Government and Democracy in Botswana: Observational and Experimental Evidence on the Effects of E-Government Usage on Political Attitudes

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Bante, Jana et al. Working Paper E-government and democracy in Botswana: Observational and experimental evidence on the effects of e-government usage on political attitudes Discussion Paper, No. 16/2021 Provided in Cooperation with: German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn Suggested Citation: Bante, Jana et al. (2021) : E-government and democracy in Botswana: Observational and experimental evidence on the effects of e-government usage on political attitudes, Discussion Paper, No. 16/2021, ISBN 978-3-96021-153-2, Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn, http://dx.doi.org/10.23661/dp16.2021 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/234177 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

African Miracle Or a Case of Mistaken Identity?

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. Pula: Botswana Journal of African Studies vol.17 (2003) nO.1 REVIEW ARTICLE Botswana: An African miracle or a case of mistaken identity? Monageng Mogalakwe Department of Sociology, University of Botswana email: [email protected] An African Miracle: State and Class Leadership and Colonial Legacy In Botswana Development, by Abdi Ismail Samatar, Heinemann, 1999, pp.217, ISBN: 0-325- 00068-9 About a decade ago, the left leaning Review of African Political Economy (ROAPE) published an article by Hoogvelt et al (1992) entitled: 'The World Bank and Africa: A Case of Mistaken Identity'. The article criticised the World Bank's simplistic tendency to lump together African countries as if Africa is one entity. In their critique of the World Bank's simplistic methodology, the authors cite several statements from the bank's reports that posit, inter alia, that Africa is facing deepening crisis because of weak economic growth, low levels of manufacturing, poor export performance, declining industrial output, climbing debt, fal1ing per capita incomes, low levels of investments and savings, weak institutional capacity and deteriorating social indicators, al1 compounded by accelerating population growth. Whilst the World Bank argues that these key variables provide for a commonality that requires a common strategy, Hoogvelt et al used a range of statistical techniques of cluster and discriminant analysis through which they found not ONE, but FOUR distinct types of countries in Africa. -

Botswana. Supervisor of Elections. . Report to the Minister of State on the General Elections, 1974

Botswana. Supervisor of Elections. Report to the Minister of State on the general elections, 1974. Gaborone, Government Printer [1974?] / 30p. 29cm. 1. Botswana-Pol. & govt. 2. Elections- Botswana. I • INDEX Page. Report to the Minister of State on the General Elections, 1974 Evaluation and Recommendations *"* Conclusion ...... 2 - • • • • 4 Title Appendix lA' A list of Constituencies, Polling Districts and Polling Stations showing the number of registered voters by constituency and polling station Appendix '/?' Authenticating Officers appointed in accordance with the Presidential Elections (Supplementary Provisions) Act >;• 12 Appendix 'C A list of Returning Officers for the Parliamentary Elections • ! l 13 Appendix Z)' A list of Returning Officers for the Local Government Elections .. ^ . 14 Appendix 'ZT Summary of the Parliamentary election results Appendix lF 17 A list of candidates in the Parliamentary Election showing the number of votes cast for each, number of votes in each constituency, and the majority gained by the winning can- didate and the percentage poll 18 Appendix '6" Summary of Local Government Election results by District or Town Council 20 Appendix 'IT A list of candidates in the Local Government election showing the number of votes cast tor each, the number of voters in each Polling District, the majority gained by the win- ning candidate, and the percentage poll / 22 Appendix T A list of political Parries registered under Section 149 of the Electoral Act 1969 30 Appendix ' J" A Report on-expenditure on the 1974 General Election 30 Sir, REPORT TO ™E MINISTER. OF STATE ON THE GENERAL ELECTIONS, 1974 SSSITOSSS: S.»=^^HS£s~rr?' Lo^l Government Election* become generally available to the public - - - > »S5S^S^as: • l^^sstsss^aSSSS^5^^-^-"5 5. -

Copyright Government of Botswana CHAPTER 69:04

CHAPTER 69:04 - PUBLIC ROADS: SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION INDEX TO SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION Declaration of Public Roads and Width of Public Roads Order DECLARATION OF PUBLIC ROADS AND WIDTH OF PUBLIC ROADS ORDER (under section 2 ) (11th March, 1960 ) ARRANGEMENT OF PARAGRAPHS PARAGRAPHS 1. Citation 2. Establishment and declaration of public roads 3. Width of road Schedule G.N. 5, 1960, L.N. 84, 1966, G.N. 46, 1971, S.I. 106, 1971, S.I. 94, 1975, S.I. 95, 1975, S.I. 96, 1975, S.I. 97, 1982, S.I. 98, 1982, S.I. 99, 1982, S.I. 100, 1982, S.I. 53, 1983, S.I. 90, 1983, S.I. 6, 1984, S.I. 7, 1984, S.I. 151, 1985, S.I. 152, 1985. 1. Citation This Order may be cited as the Declaration of Public Roads and Width of Public Roads Order. 2. Establishment and declaration of public roads The roads described in the Schedule hereto are established and declared as public roads. 3. Width of road The width of every road described in the Schedule hereto shall be 30,5 metres on either side of the general run of the road. SCHEDULE Description District Distance in kilometres RAMATLABAMA-LOBATSE Southern South 48,9 East Commencing at the Botswana-South Africa border at Ramatlabama and ending at the southern boundary of Lobatse Township as shown on Plan BP225 deposited with the Director of Surveys and Lands, Gaborone. LOBATSE-GABORONE South East 65,50 Copyright Government of Botswana ("MAIN ROAD") Leaving the statutory township boundary of Lobatse on the western side of the railway and entering the remainder of the farm Knockduff No.