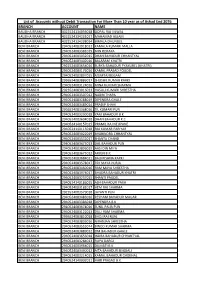

Appendix 8 List of Research Participants SN Name VDC Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Documentation in the Aftermath of the 2015 Nepal Earthquakes: a Guide to Two Archives and a Web Exhibit

Vol. 13 (2019), pp. 618–651 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24914 Revised Version Received: 4 Nov 2019 Language documentation in the aftermath of the 2015 Nepal earthquakes: A guide to two archives and a web exhibit Kristine Hildebrandt Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Tanner Burge-Beckley Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Jacob Sebok Southern Illinois University Edwardsville We describe two institutionally related archives and an online exhibit represent- ing a set of Tibeto-Burman languages of Nepal. These archives and exhibit were built to house materials resulting from documentation of twelve Tibeto-Burman languages in the aftermath of the 2015 Nepal earthquakes. This account includes a detailed discussion of the different materials recorded, and how they were pre- pared for the collections. This account also provides a comparison of the two different types of archives, the different but complementary functions they serve, and a discussion of the role that online exhibits can play in the context of language documentation archives. 1. Introduction 1 The field of documentary linguistics has made use of a widear- ray of increasingly sophisticated computing technologies in recent years in order to archive, catalogue, and ultimately preserve vast quantities of audio, video, and text materials from endangered and vulnerable languages for future access by com- munity members and scholars alike. Notable examples of data archival reposito- ries, hosted and managed by higher educational institutions -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Journal Vol. LX. No. 2. 2018

JOURNAL OF THE ASIATIC SOCIETY VOLUME LX No. 4 2018 THE ASIATIC SOCIETY 1 PARK STREET KOLKATA © The Asiatic Society ISSN 0368-3308 Edited and published by Dr. Satyabrata Chakrabarti General Secretary The Asiatic Society 1 Park Street Kolkata 700 016 Published in February 2019 Printed at Desktop Printers 3A, Garstin Place, 4th Floor Kolkata 700 001 Price : 400 (Complete vol. of four nos.) CONTENTS ARTICLES The East Asian Linguistic Phylum : A Reconstruction Based on Language and Genes George v an Driem ... ... 1 Situating Buddhism in Mithila Region : Presence or Absence ? Nisha Thakur ... ... 39 Another Inscribed Image Dated in the Reign of Vigrahapäla III Rajat Sanyal ... ... 63 A Scottish Watchmaker — Educationist and Bengal Renaissance Saptarshi Mallick ... ... 79 GLEANINGS FROM THE PAST Notes on Charaka Sanhitá Dr. Mahendra Lal Sircar ... ... 97 Review on Dr. Mahendra Lal Sircar’s studies on Äyurveda Anjalika Mukhopadhyay ... ... 101 BOOK REVIEW Coin Hoards of the Bengal Sultans 1205-1576 AD from West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand, Assam and Bangladesh by Sutapa Sinha Danish Moin ... ... 107 THE EAST ASIAN LINGUISTIC PHYLUM : A RECONSTRUCTION BASED ON LANGUAGE AND GENES GEORGE VAN DRIEM 1. Trans-Himalayan Mandarin, Cantonese, Hakka, Xiâng, Hokkien, Teochew, Pínghuà, Gàn, Jìn, Wú and a number of other languages and dialects together comprise the Sinitic branch of the Trans-Himalayan language family. These languages all collectively descend from a prehistorical Sinitic language, the earliest reconstructible form of which was called Archaic Chinese by Bernard Karlgren and is currently referred to in the anglophone literature as Old Chinese. Today, Sinitic linguistic diversity is under threat by the advance of Mandarin as a standard language throughout China because Mandarin is gradually taking over domains of language use that were originally conducted primarily in the local Sinitic languages. -

12Th Himalayan Languages Symposium & 27Th Annual

12th Himalayan Languages Symposium & 27th Annual Conference of Linguistic Society of Nepal Program Schedule November 26, 2006 Opening 9.30 – 11.00 Chief Guest: Dr. Kamal Krishna Joshi Chairman University Grants Commission Welcome Speech: Mr. Bijay Kumar Rauniyar Secretary-Treasurer Linguistic Society of Nepal Presidential Address: Prof. Dr. Jai Raj Awasthi President Linguistic Society of Nepal Keynote Speech: Dr. Anju Saxena Department of Linguistics and Philology Uppsala University Sweden Messages: (Speakers to be mentioned later) Message from the Chief Guest: Dr. Kamal Krishna Joshi Vote of Thanks: Prof. Dr. Govind Raj Bhattarai Vice-president Linguistic Society of Nepal Refreshment 11.30 – 12.00 1 Sessions Session I: 12.00 – 13.40 Session I A: Phonology and Morphophonemics Session I B: Morphology and Morphology Gong vowels and tones Personal pronouns in Dhangar / Jhangar David Bradley Y. P. Yadava, Ram Kishun Urawn and Suren Sapkota Sound change in Kirānti-Kõits across Western Kirānti Verbal morphology in Gopali language Lal-Shyãkarelu Rapacha Rudra Laxmi Shrestha Statistical study on Nepali syllable structure Compound verb in Chintang R. Lohani and B. N. Regmi Novel Kishore Rai and Netra Prasad Paudyal Morphophonemics of Kumal verbs Tenses and aspects in Dhankute Tamang Bhim Lal Gautam Kedar Prasad Poudel Lunch Break: 13.40 – 14.30 Session II: 14.30 – 17.15 Session II B: Session II B: Sociolinguistics Session II A: Language Documentation and Sociolinguistics Ethno-genetics and ethno-linguistics of six indigenous Language documentation -

An Ethnobiological Study of the Tamang People

Our Nature (2003) 1: 37-41 An Ethnobiological Study of the Tamang People Ganesh Tamang* Central Department of Zoology, Kirtipur Abstract Tamangs are one of the major ethnic groups of Nepal. Ethnobiological investigation of Tamang people of Gorsyang Village Development Committee of Nuwakot district was carried out. Information was documented from structured questionnaire and interviews with local people. They were found to have rich indigenous knowledge. They use different 12 animal names as calendar. A total of 11 animal species and 44 plant species were found to be used in medicinal purpose. Viscera of Hystrix brachyura, pancreas of fish and flesh of Rana tigrina were found using in the treatment of asthma, jaundice and pneumonia. The fur of Lepus nigricollis is used to stop bleeding. Acorus calamus, Centilla asiatica and Terminalia chebula are the important medicinal plants, which they use to control throat, urine and gastric problems. The stem extract of Tinospora cordifolia is used in menstruation problems. Introduction said that they were horse traders. “Ta” in Tamangs are one of the major Tibeto- Tibetan means horse; “Mang” means traders Burmese speaking communities in Nepal. (Bista 1967). They have very rich They believe that they originally came ethnobiological knowledge. from Tibet. The entire community of Their social, cultural, economic and Tamang is divided into several sub castes religious practices are, in one way or known as 'thar'. Each 'thar' has its own other, linked to plants and animals. For name like Sangden, Bomjan, Yonjan, example, in the ‘Loh’ (age calculation Pakhrin, etc. Languagewise, these people calender), twelve different animals have are the third largest ethnic group in the been used. -

Institutional Determinants of Poverty Among Indigenous Peoples of Nepal Gyanesh Lama Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 5-24-2012 Global Poverty - Local Problem: Institutional Determinants of Poverty Among Indigenous Peoples of Nepal Gyanesh Lama Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Lama, Gyanesh, "Global Poverty - Local Problem: Institutional Determinants of Poverty Among Indigenous Peoples of Nepal" (2012). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 705. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/705 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS George Warren Brown School of Social Work Dissertation Examination Committee: Santa Pandey, Chair Geoff Childs David Gillespie Itai Sened Michael Sherraden Molly Tovar Global Poverty – Local Problem: Instituional Determinants of Poverty Among Indigenous Peoples in Nepal By Gyanesh Kumar Lama A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2012 St. Louis, Missouri Acknowledgements Since I came to the United States, the most frequently asked questions have been “How did you come to America?” and “How did you get into Washington University?” These questions are loaded with curiosity, and perhaps disbelief, that a person like me, a village boy from a rural mountain of the Himalayas, could make it to one of the best and most expensive universities in America. -

Adaptation and Identity of Yolmo People Contributiolls to Nepalese Studies, Vol

90 Occasional Papers Regmi, Mahesh C. 1976, Lalldowllership in Nepal, Berkeley: University of California Press. Rosser, Colin 1966, "Social Mobility in the Newar Caste System" in C. Von Ftirer-Haimendorf (ed.) Caste and Kill ill Nepal. Illdia and Cye/oll, Bombey: Asia Publishing House. Srinivas, M.N. 1966, Socia/ Challge ill Modern Illdia, Berkeley: ADAPTATION AND University of California Press IDENTITY OF YOLMO Sharma, Balchandra 1978 (2033 v.s.), Nepa/ko Airihasik Ruparekha (An Outline of the History of Nepal), Baranasi: Krishna Kumari Devi. Biood Pokharel Sharma, Prayag Raj 2004, "Introduction" in Andras HOfer, 2004, The Caste Hierarchy alld the State in Nepal: A Study ofthe Mu/ki Aill of1854, Kathmandu: Himal Books. An Overview Sharma, Prayag Raj 1978, "Nepal: Hindu-Tribal Interface" III This article focuses on adaptation and identity of Yolmo people ContributiOlls to Nepalese Studies, Vol. 16, No. I, pp. 1-4. living in the western part of the Sindhupalchok district. The Yolmo are traditionally herders and traders but later they diversified their economy and are now relying on tourism, wage labour and work aboard for income. It is believed that they arrived in the Melamchi area from Tibet from the 18'" century onwards. This article basically concerns on how Yolmo change their adaptive strategy for their survival and how did they become successful in keep their identity even though they have a small population. The economic adaptation in mountain region is very difficult due to marginal land and low productivity. Therefore they diversified their economy in multiple sectors to cope with the environment. Bishop states that "diversification involves exploiting one or more zones and managing several economic activities simultaneously" (1998:22). -

My Name Is Maya Lama/Hyolmo/Syuba’: Negotiating Identity in Hyolmo Diaspora Communities Lauren Gawne Nanyang Technological University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SOAS Research Online ‘My name is Maya Lama/Hyolmo/Syuba’: Negotiating identity in Hyolmo diaspora communities Lauren Gawne Nanyang Technological University Pre-publication version Abstract Hyolmo communities have resided in the Lamjung and Ramechhap districts oF Nepal For at least a century, and are part oF a historical trend oF group migration away From the Hyolmo homelands. These communities have taken diFFerent approaches to constructing their identities as belonging to the Hyolmo diaspora; in Lamjung, people readily identiFy as Hyolmo, while in Ramechhap people accept their Hyolmo history, but have also developed an identity as Kagate (and now Syuba). In this paper I trace these groups’ migration histories. I then look at the variety oF names used in reFerence to these communities, which helps us to understand their historical and contemporary relationships with Hyolmo. Finally, I examine contemporary cultural and linguistic practices in Ramechhap and Lamjung, to see how communities perForm their identity as Kagate or Hyolmo, and as modern Buddhists oF Tibetan origin in Nepal. 1. Introduction The majority oF Hyolmo speakers reside in the Nuwakot, Sindhupalchok and Rasuwa districts of Nepal, to the north oF Kathmandu, but there are also sustained populations that have lived in other areas for several generations, including Lamjung, Ramechhap and Ilam in Nepal, and Darjeeling in India. In this paper I discuss the Hyolmo1 community in Lamjung, and the Kagate community 1 In this paper I use the spelling Hyolmo as the deFault variant in keeping with the other authors of this volume, although in my own work I use the spelling Yolmo, particularly in relation to the Lamjung community. -

The Politics of Culture and Identity in Contemporary Nepal

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 20 Number 1 Himalayan Research Bulletin no. 1 & Article 7 2 2000 Roundtable: The Politics of Culture and Identity in Contemporary Nepal Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation . 2000. Roundtable: The Politics of Culture and Identity in Contemporary Nepal. HIMALAYA 20(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol20/iss1/7 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Roundtable: The Politics of Culture and Identity in Contemporary Nepal Organizers: William F. Fisher and Susan Hangen Panelists: Karl-Heinz Kramer, Laren Leve, David Romberg, Mukta S. Tamang, Judith Pettigrew,and Mary Cameron William F. Fisher and Susan Hangen local populations involved in and affected by the janajati Introduction movement in Nepal. In the years since the 1990 "restoration" of democracy, We asked the roundtable participants to consider sev ethnic activism has become a prominent and, for some, a eral themes that derived from our own discussion: worrisome part of Nepal's political arena. The "janajati" 1. To what extent and to what end does it make sense movement is composed of a mosaic of social organizations to talk about a "janajati movement"? Reflecting a wide and political parties dominated by groups of peoples who variety of intentions, goals, definitions, and strategies, do have historically spoken Tibeto-Burman languages. -

The Chantyal Language1 Michael Noonan University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CrossAsia-Repository The Chantyal Language1 Michael Noonan University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee 1. introduction The Chantyal language is spoken by approximately 2000 of the 10,000 ethnic Chantyal. The Chantyal live in the Baglung and Myagdi Districts of Nepal; the villages where the Chantyal language is spoken are all located in the eastern portion of the Myagdi District and include the villages of Mangale Kh‚ni, Dw‚ri, Ghy“s Khark‚, Caura Kh‚ni, Kuine Kh‚ni, Th‚r‚ Kh‚ni, P‚tle Khark‚, M‚l‚mp‚h‚r, and Malk‚b‚ng. There is relatively little linguistic variation among these villages, though where differences exist, it is the speech of Mangale Kh‚ni that is represented here. The Chantyal language is a member of the Tamangic group [along with Gurung, Thakali, Nar-Phu and Tamang, the last two of which are discussed in this volume]. Within the group, it is lexically and grammatically closest to Thakali. Assessment of the internal relations within the group is complicated by a number of factors, among which is the fact that shared innovations may be the product of geographic contiguity as much as shared genetic background. At the moment, the most likely classification is as fol- lows: Tamangic Tamang complex Gurungic Manangba—Nar-Phu complex Gurung Thakali—Chantyal Thakali Chantyal Chantyal, however, is in many respects the most deviant member of the group, lacking a tone system and having borrowed a large portion of its lexicon from Nepali. -

Branch Account Name

List of Accounts without Debit Transaction For More Than 10 year as of Ashad End 2076 BRANCH ACCOUNT NAME BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134056018 GOPAL RAJ SILWAL BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134231017 MAHAMAD ASLAM BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134298014 BIMALA DHUNGEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083918012 KAMALA KUMARI MALLA BENI BRANCH 2940524083381019 MIN ROKAYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083932015 DHAN BAHADUR CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083402016 BALARAM KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2922524083654016 SURYA BAHADUR PYAKUREL (KHATRI) BENI BRANCH 2940524083176016 KAMAL PRASAD POUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083897015 MUMTAJ BEGAM BENI BRANCH 2936524083886017 SHUSHIL KUMAR KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083124016 MINA KUMARI SHARMA BENI BRANCH 2923524083016013 HASULI KUMARI SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083507012 NABIN THAPA BENI BRANCH 2940524083288019 DIPENDRA GHALE BENI BRANCH 2940524083489014 PRADIP SHAHI BENI BRANCH 2936524083368016 TIL KUMARI PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083230018 YAM BAHADUR B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083604018 DHAN BAHADUR K.C BENI BRANCH 2940524140157015 PRAMIL RAJ NEUPANE BENI BRANCH 2940524140115018 RAJ KUMAR PARIYAR BENI BRANCH 2940524083022019 BHABINDRA CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083532017 SHANTA CHAND BENI BRANCH 2940524083475013 DAL BAHADUR PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083896019 AASI DIN MIYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083675012 ARJUN B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083684011 BALKRISHNA KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083578017 TEK MAYA PURJA BENI BRANCH 2940524083460016 RAM MAYA SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083974017 BHADRA BAHADUR KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2940524083237015 SHANTI PAUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524140186015 -

Report on the Relationship Between Yolmo and Kagate Journal Issue

Peer Reviewed Title: Report on the relationship between Yolmo and Kagate Journal Issue: Himalayan Linguistics, 12(2) Author: Gawne, Lauren, University of Melbourne Publication Date: 2013 Permalink: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/7vd5d2vm Keywords: Tibeto-Burman, Central Bodic, Yolmo, Kagate, Lexicon Local Identifier: himalayanlinguistics_23716 Abstract: Yolmo and Kagate are two closely related Tibeto-Burman languages of Nepal. This paper provides a general overview of these two languages, including several dialects of Yolmo. Based on existent sources, and my own fieldwork, I present an ethnographic summary of each group of speakers, and the linguistic relationship between their mutually intelligible dialects. I also discuss a set of key differences that have been observed in regards to these languages, including the presence or absence of tone contours, verb stems and honorific lexical items. Although Yolmo and Kagate could be considered dialects of the same language, there are sufficient historical and political motivations for considering them as separate languages. Finally, I look at the status of the "Kyirong-Kagate" sub-branch of Tibetic languages in Tournadre’s (2005) classification, and argue that for reasons discussed in this paper it should instead be referred to as "Kyirong-Yolmo." Copyright Information: Copyright 2013 by the article author(s). This work is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs4.0 license, http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ eScholarship provides open access, scholarly publishing services to the University of California and delivers a dynamic research platform to scholars worldwide. Himalayan Linguistics Report on the relationship between Yolmo and Kagate Lauren Gawne The University of Melbourne ABSTRACT Yolmo and Kagate are two closely related Tibeto-Burman languages of Nepal.