Mainstream Religious Domain in Nepal a Contradiction and Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Parks and Iccas in the High Himalayan Region of Nepal: Challenges and Opportunities

[Downloaded free from http://www.conservationandsociety.org on Tuesday, June 11, 2013, IP: 129.79.203.216] || Click here to download free Android application for this journal Conservation and Society 11(1): 29-45, 2013 Special Section: Article National Parks and ICCAs in the High Himalayan Region of Nepal: Challenges and Opportunities Stan Stevens Department of Geosciences, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In Nepal, as in many states worldwide, national parks and other protected areas have often been established in the customary territories of indigenous peoples by superimposing state-declared and governed protected areas on pre-existing systems of land use and management which are now internationally considered to be Indigenous Peoples’ and Community Conserved Territories and Areas (ICCAs, also referred to Community Conserved Areas, CCAs). State intervention often ignores or suppresses ICCAs, inadvertently or deliberately undermining and destroying them along with other aspects of indigenous peoples’ cultures, livelihoods, self-governance, and self-determination. Nepal’s high Himalayan national parks, however, provide examples of how some indigenous peoples such as the Sharwa (Sherpa) of Sagarmatha (Mount Everest/Chomolungma) National Park (SNP) have continued to maintain customary ICCAs and even to develop new ones despite lack of state recognition, respect, and coordination. The survival of these ICCAs offers Nepal an opportunity to reform existing laws, policies, and practices, both to honour UN-recognised human and indigenous rights that support ICCAs and to meet International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) standards and guidelines for ICCA recognition and for the governance and management of protected areas established in indigenous peoples’ territories. -

We Take Pride in Jobs Well Done

We take pride in jobs well done. JAGADAMBA PRESS #128 17 - 23 January 2003 16 pages Rs 25 [email protected] Tel: (01) 521393, 543017, 547018 Fax: (01) 536390 HEMLATA RAI, with JANAK NEPAL Manjushree in ○○○○○○○○○○○○ ○○○○○○○○ NEPALGANJ hoever killed their parents, the talks to Samrat children end up in the same place. W Sangita Yadav’s father was a farmer in Leave the kids alone Banke district. The Maoists came while he was the needs of those who are already affected.” Children recruited by eating, dragged him out of his house, beat and One of the undocumented aspects of the tortured him in front of his family, and killed Maoists to carry their conflict is the growing number of internally him. Sarala Dahal’s father was a teacher in the rucksacks rest at a tea displaced families. This has increased the same district. He was killed after surrendering house in Kalikot number of children in the district headquarters, to the security forces. district in June. townships and in Kathmandu Valley who have Sarala and Sangita are both being raised in a lost their traditional village support Novelist Manjushree Thapa, author of the child shelter which has just opened in mechanisms. School closures and threats of much-acclaimed The Tutor of History has Nepalganj by the charity group, Sahara. “We forced recruitment of one child per family by a cyber-chat with fellow-author and don’t really care who killed their parents or Maoists have added to the influx of children. A compatriot, Samrat Upadhyay who has relatives, we want to protect the future of these recent survey in the insurgency hotbed of just published his second book, The Guru children, and they all get equal care here,” says Rukum alone found that out of 1,000 people of Love in the United States. -

The Sherpa and the Snowman

THE SHERPA AND THE SNOWMAN Charles Stonor the "Snowman" exist an ape DOESlike creature dwelling in the unexplored fastnesses of the Himalayas or is he only a myth ? Here the author describes a quest which began in the foothills of Nepal and led to the lower slopes of Everest. After five months of wandering in the vast alpine stretches on the roof of the world he and his companions had to return without any demon strative proof, but with enough indirect evidence to convince them that the jeti is no myth and that one day he will be found to be of a a very remarkable man-like ape type thought to have died out thousands of years before the dawn of history. " Apart from the search for the snowman," the narrative investigates every aspect of life in this the highest habitable region of the earth's surface, the flora and fauna of the little-known alpine zone below the snow line, the unexpected birds and beasts to be met with in the Great Himalayan Range, the little Buddhist communities perched high up among the crags, and above all the Sherpas themselves that stalwart people chiefly known to us so far for their gallant assistance in climbing expeditions their yak-herding, their happy family life, and the wav they cope with the bleak austerity of their lot. The book is lavishly illustrated with the author's own photographs. THE SHERPA AND THE SNOWMAN "When the first signs of spring appear the Sherpas move out to their grazing grounds, camping for the night among the rocks THE SHERPA AND THE SNOWMAN By CHARLES STONOR With a Foreword by BRIGADIER SIR JOHN HUNT, C.B.E., D.S.O. -

May 2013 India Review Ambassador’S PAGE America Needs More High-Skilled Worker Visas a Generous Visa Policy for Highly Skilled Workers Would Help Everyone

A Publication of the Embassy of India, Washington, D.C. May 1, 2013 I India RevieI w Vol. 9 Issue 5 www.indianembassy.org IMFC Finance Ministers and Bank Governors during a photo-op at the IMF Headquarters in Washington, D.C. on April 20. Overseas capital best protected in India — Finance Minister P. Chidambaram n India announces n scientist U.R. Rao n Pran honored incentives to boost inducted into with Dadasaheb exports Satellite Hall of Fame Phalke award Ambassador’s PAGE India is ready for U.S. natural gas There is ample evidence that the U.S. economy will benefit if LNG exports are increased he relationship between India and the United States is vibrant and growing. Near its T heart is the subject of energy — how to use and secure it in the cleanest, most efficient way possible. The India-U.S. Energy Dialogue, established in 2005, has allowed our two countries to engage on many issues. Yet as India’s energy needs con - tinue to rise and the U.S. looks to expand the marketplace for its vast cache of energy resources, our partner - ship stands to be strengthened even facilities and ports to distribute it macroeconomic scenarios, and under further. globally. every one of them the U.S. economy Despite the global economic slow - There is a significant potential for would experience a net benefit if LNG down, India’s economy has grown at a U.S. exports of LNG to grow expo - exports were increased. relatively brisk pace over the past five nentially. So far, however, while all ter - A boost in LNG exports would have years and India is now the world’s minals in the U.S. -

Language Politics and State Policy in Nepal: a Newar Perspective

Language Politics and State Policy in Nepal: A Newar Perspective A Dissertation Submitted to the University of Tsukuba In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Public Policy Suwarn VAJRACHARYA 2014 To my mother, who taught me the value in a mother tongue and my father, who shared the virtue of empathy. ii Map-1: Original Nepal (Constituted of 12 districts) and Present Nepal iii Map-2: Nepal Mandala (Original Nepal demarcated by Mandalas) iv Map-3: Gorkha Nepal Expansion (1795-1816) v Map-4: Present Nepal by Ecological Zones (Mountain, Hill and Tarai zones) vi Map-5: Nepal by Language Families vii TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents viii List of Maps and Tables xiv Acknowledgements xv Acronyms and Abbreviations xix INTRODUCTION Research Objectives 1 Research Background 2 Research Questions 5 Research Methodology 5 Significance of the Study 6 Organization of Study 7 PART I NATIONALISM AND LANGUAGE POLITICS: VICTIMS OF HISTORY 10 CHAPTER ONE NEPAL: A REFLECTION OF UNITY IN DIVERSITY 1.1. Topography: A Unique Variety 11 1.2. Cultural Pluralism 13 1.3. Religiousness of People and the State 16 1.4. Linguistic Reality, ‘Official’ and ‘National’ Languages 17 CHAPTER TWO THE NEWAR: AN ACCOUNT OF AUTHORS & VICTIMS OF THEIR HISTORY 2.1. The Newar as Authors of their history 24 2.1.1. Definition of Nepal and Newar 25 2.1.2. Nepal Mandala and Nepal 27 Territory of Nepal Mandala 28 viii 2.1.3. The Newar as a Nation: Conglomeration of Diverse People 29 2.1.4. -

The Chantyal Language1 Michael Noonan University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CrossAsia-Repository The Chantyal Language1 Michael Noonan University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee 1. introduction The Chantyal language is spoken by approximately 2000 of the 10,000 ethnic Chantyal. The Chantyal live in the Baglung and Myagdi Districts of Nepal; the villages where the Chantyal language is spoken are all located in the eastern portion of the Myagdi District and include the villages of Mangale Kh‚ni, Dw‚ri, Ghy“s Khark‚, Caura Kh‚ni, Kuine Kh‚ni, Th‚r‚ Kh‚ni, P‚tle Khark‚, M‚l‚mp‚h‚r, and Malk‚b‚ng. There is relatively little linguistic variation among these villages, though where differences exist, it is the speech of Mangale Kh‚ni that is represented here. The Chantyal language is a member of the Tamangic group [along with Gurung, Thakali, Nar-Phu and Tamang, the last two of which are discussed in this volume]. Within the group, it is lexically and grammatically closest to Thakali. Assessment of the internal relations within the group is complicated by a number of factors, among which is the fact that shared innovations may be the product of geographic contiguity as much as shared genetic background. At the moment, the most likely classification is as fol- lows: Tamangic Tamang complex Gurungic Manangba—Nar-Phu complex Gurung Thakali—Chantyal Thakali Chantyal Chantyal, however, is in many respects the most deviant member of the group, lacking a tone system and having borrowed a large portion of its lexicon from Nepali. -

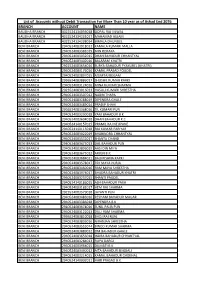

Branch Account Name

List of Accounts without Debit Transaction For More Than 10 year as of Ashad End 2076 BRANCH ACCOUNT NAME BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134056018 GOPAL RAJ SILWAL BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134231017 MAHAMAD ASLAM BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134298014 BIMALA DHUNGEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083918012 KAMALA KUMARI MALLA BENI BRANCH 2940524083381019 MIN ROKAYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083932015 DHAN BAHADUR CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083402016 BALARAM KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2922524083654016 SURYA BAHADUR PYAKUREL (KHATRI) BENI BRANCH 2940524083176016 KAMAL PRASAD POUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083897015 MUMTAJ BEGAM BENI BRANCH 2936524083886017 SHUSHIL KUMAR KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083124016 MINA KUMARI SHARMA BENI BRANCH 2923524083016013 HASULI KUMARI SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083507012 NABIN THAPA BENI BRANCH 2940524083288019 DIPENDRA GHALE BENI BRANCH 2940524083489014 PRADIP SHAHI BENI BRANCH 2936524083368016 TIL KUMARI PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083230018 YAM BAHADUR B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083604018 DHAN BAHADUR K.C BENI BRANCH 2940524140157015 PRAMIL RAJ NEUPANE BENI BRANCH 2940524140115018 RAJ KUMAR PARIYAR BENI BRANCH 2940524083022019 BHABINDRA CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083532017 SHANTA CHAND BENI BRANCH 2940524083475013 DAL BAHADUR PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083896019 AASI DIN MIYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083675012 ARJUN B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083684011 BALKRISHNA KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083578017 TEK MAYA PURJA BENI BRANCH 2940524083460016 RAM MAYA SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083974017 BHADRA BAHADUR KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2940524083237015 SHANTI PAUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524140186015 -

SANA GUTHI and the NEWARS: Impacts Of

SANA GUTHI AND THE NEWARS: Impacts of Modernization on Traditional Social Organizations Niraj Dangol Thesis Submitted for the Degree: Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education University of Tromsø Norway Autumn 2010 SANA GUTHI AND THE NEWARS: Impacts of Modernization on Traditional Social Organizations By Niraj Dangol Thesis Submitted for the Degree: Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies Faculty of Social Science, University of Tromsø Norway Autumn 2010 Supervised By Associate Professor Bjørn Bjerkli i DEDICATED TO ALL THE NEWARS “Newa: Jhi Newa: he Jui” We Newars, will always be Newars ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I regard myself fortunate for getting an opportunity to involve myself as a student of University of Tromsø. Special Thanks goes to the Sami Center for introducing the MIS program which enables the students to gain knowledge on the issues of Indigeneity and the Indigenous Peoples. I would like to express my grateful appreciation to my Supervisor, Associate Prof. Bjørn Bjerkli , for his valuable supervision and advisory role during the study. His remarkable comments and recommendations proved to be supportive for the improvisation of this study. I shall be thankful to my Father, Mr. Jitlal Dangol , for his continuous support and help throughout my thesis period. He was the one who, despite of his busy schedules, collected the supplementary materials in Kathmandu while I was writing this thesis in Tromsø. I shall be thankful to my entire family, my mother and my sisters as well, for their continuous moral support. Additionally, I thank my fiancé, Neeta Maharjan , who spent hours on internet for making valuable comments on the texts and all the suggestions and corrections on the chapters. -

Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal

UNEQUAL CITIZENS UNEQUAL37966 Public Disclosure Authorized CITIZENS Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal Caste and Ethnic Exclusion Gender, THE Department For International WORLD DFID Development SUMMARY BANK The World Bank DFID Nepal Nepal Office P.O. Box 106 P.O. Box 798 Kathmandu, Nepal Yak and Yeti Hotel Tel.: 5542980 Complex Fax: 5542979 Durbar Marg Public Disclosure Authorized Kathmandu, Nepal Tel.: 4226792, 4226793 E-mail Fax: 4225112 [email protected] Websites www.worldbank.org.np, Website www.bishwabank.org.np www.dfid.gov.uk Public Disclosure Authorized DFID Development International Department For ISBN 99946-890-0-2 9 799994 689001 > BANK WORLD THE Public Disclosure Authorized A Kathmandu businessman gets his shoes shined by a Sarki. The Sarkis belong to the leatherworker subcaste of Nepal’s Dalit or “low caste” community. Although caste distinctions and the age-old practices of “untouchability” are less rigid in urban areas, the deeply entrenched caste hierarchy still limits the life chances of the 13 percent of Nepal’s population who belong to the Dalit caste group. UNEQUAL CITIZENS Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal SUMMARY THE Department For International WORLD DFID Development BANK THE Department For International WORLD DFID Development BANK The World Bank DFID Nepal Nepal Office P.O. Box 106 P.O. Box 798 Kathmandu, Nepal Yak and Yeti Hotel Complex Tel.: 5542980 Durbar Marg Fax: 5542979 Kathmandu, Nepal Tel.: 4226792, 4226793 E-mail Fax: 4225112 [email protected] Websites www.worldbank.org.np, Website www.bishwabank.org.np www.dfid.gov.uk A copublication of The World Bank and the Department For International Development, U.K. -

Identity-Based Conflict and the Role of Print Media in the Pahadi Community of Contemporary Nepal Sunil Kumar Pokhrel Kennesaw State University

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Dissertations, Theses and Capstone Projects 7-2015 Identity-Based Conflict and the Role of Print Media in the Pahadi Community of Contemporary Nepal Sunil Kumar Pokhrel Kennesaw State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/etd Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Pokhrel, Sunil Kumar, "Identity-Based Conflict and the Role of Print Media in the Pahadi Community of Contemporary Nepal" (2015). Dissertations, Theses and Capstone Projects. Paper 673. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses and Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IDENTITY-BASED CONFLICT AND PRINT MEDIA IDENTITY-BASED CONFLICT AND THE ROLE OF PRINT MEDIA IN THE PAHADI COMMUNITY OF CONTEMPORARY NEPAL by SUNIL KUMAR POKHREL A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Conflict Management in the College of Humanities and Social Sciences Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, Georgia March 2015 IDENTITY-BASED CONFLICT AND PRINT MEDIA © 2015 Sunil Kumar Pokhrel ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Recommended Citation Pokhrel, S. K. (2015). Identity-based conflict and the role of print media in the Pahadi community of contemporary Nepal. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, Georgia, United States of America. IDENTITY-BASED CONFLICT AND PRINT MEDIA DEDICATION My mother and father, who encouraged me toward higher study, My wife, who always supported me in all difficult circumstances, and My sons, who trusted me during my PhD studies. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Note: Page numbers in italics refer to figures and tables. 16R dune site, 36, 43, 440 Adittanallur, 484 Adivasi peoples see tribal peoples Abhaipur, 498 Adiyaman dynasty, 317 Achaemenid Empire, 278, 279 Afghanistan Acharyya, S.K., 81 in “Aryan invasion” hypothesis, 205 Acheulean industry see also Paleolithic era in history of agriculture, 128, 346 in Bangladesh, 406, 408 in human dispersals, 64 dating of, 33, 35, 38, 63 in isotope analysis of Harappan earliest discovery of, 72 migrants, 196 handaxes, 63, 72, 414, 441 skeletal remains found near, 483 in the Hunsgi and Baichbal valleys, 441–443 as source of raw materials, 132, 134 lack of evidence in northeastern India for, 45 Africa major sites of, 42, 62–63 cultigens from, 179, 347, 362–363, 370 in Nepal, 414 COPYRIGHTEDhominoid MATERIAL migrations to and from, 23, 24 in Pakistan, 415 Horn of, 65 related hominin finds, 73, 81, 82 human migrations from, 51–52 scholarship on, 43, 441 museums in, 471 Adam, 302, 334, 498 Paleolithic tools in, 40, 43 Adamgarh, 90, 101 research on stature in, 103 Addanki, 498 subsistence economies in, 348, 353 Adi Badri, 498 Agara Orathur, 498 Adichchanallur, 317, 498 Agartala, 407 Adilabad, 455 Agni Purana, 320 A Companion to South Asia in the Past, First Edition. Edited by Gwen Robbins Schug and Subhash R. Walimbe. © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2016 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 0002649130.indd 534 2/17/2016 3:57:33 PM INDEX 535 Agra, 337 Ammapur, 414 agriculture see also millet; rice; sedentism; water Amreli district, 247, 325 management Amri, -

A Study of Religious Beliefs and the Festivals of the Tribal's of Tripura

Volume 4, Issue 5, May – 2019 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology ISSN No:-2456-2165 A Study of Religious Beliefs and the Festivals of the Tribal’s of Tripura with Special Reference to – Tripuris Sujit Kumar Das Research Scholar, Department of Indian Comparative Literature Assam University, Silchar Abstract:- It is believed that, “Religion is commonly Hinduism is not a like to Christianity on religious point understood on a belief that mankind has in visible ground. controlling power with a related emotion and sense of morality. The common features and nature of religion Many of the tribes of Tripura come moor and belief of the Tribal Religion are some as in the case of moor under influence of Hindu way of life, and their any so called higher. It is true that in the field of the tribal cults were roughly assimilated to Hinduism by simplest beliefs and practices of Tribal communities, Brahmins who are said to brought by Royal house of the non-Tribal virtuous people are not different from Tripura. But animism, the primitive from of religion, is them. But yet, there are differences on pragmatic still traceable in tribal’s thinking and out-looks among grounds ‘Which are not logically valid’. At present it the Hindu & Buddhist tribes. Now a new trend has must be suffice to say that “in any treatment of Tribal been found among them in which respect for their own beliefs and practices, it would be useful to sued indigenous culture and their identity are the dominant personal prejudices, or at least keep judgment in facts.