Politics of R Esistance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustainable Tourism Enhancement in Nepal's Protected Areas Public Disclosure Authorized

Sustainable Tourism Enhancement in Nepal's Protected Areas Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized National Trust for Nature Conservation GPO Box 3712, Khumaltar, Lalitpur, Nepal May 2020 Executive Summary 1. Description of the Project: Tourism is one of the major contributors to the sustainable economy of Nepal. The direct contribution of the tourism sector in the national GDP was at 4% in 2017 and is forecasted to rise by 3.8% per annum to reach 4.2% in 2028 (World Travel and Tourism Council, 2018). Despite tremendous growth potential in tourism sector, Nepal stands as a low-cost tourist destination with much lower daily tourist spending than the regional average. This is a high time for Nepal to think about and harness high value nature-based tourism. Nature based tourism is a key driver of Nepal's tourism, providing the sector both comparative and competitive advantages in the unique setting of rich topographic, biological and cultural diversity. In this context, the World Bank is supporting GoN to implement the project entitled “Sustainable Tourism Enhancement in Nepal’s Protected Areas (STENPA)". Project Destinations: The project focuses on areas with Nature-Based Tourism (NBT) potential with the aim of piloting a sustainable tourism approach that can be replicated across Nepal’s protected areas (PAs). The project destinations include PA at their core, nearby gateway cities and surrounding areas with NBT potential, and has identified six PAs as the initial project destinations (Bardia, Banke Shukla Phanta and Rara National Parks, and their buffer zones; and Annapurna and Manaslu conservation Areas). -

Underdevelopment and Regional Structure of Nepal -AM

Book Review Underdevelopment and Regional Structure of Nepal -AM [This is a commentary on the book The Nature of Underdevelopment and Regional Structure of Nepal: A Marxist Analysis written by Baburam Bhattarai and published by Adroit Publishers,Delhi, in the well-known magazine Economic and Political Weekly, November 8-14, 2003, by AM as "Calcutta Diary". We may not necessarily agree with the views of the author.- Ed.] The Viswa Hindu Parishad cannot understand it. Nepal is the only Hindu Kingdom in the world; substantial sections of the people there are of north Indian ethnicity and bear names of Hindu gods and goddesses; the ruling family has long-time links with India and marries into the Rana clan dispersed along the higher and lower reaches of the Indo-Gangetic valley. And yet, Nepal is hardly benevolent land for Hindu chauvinism. Maoist communists, who are engaged in a relentless guerrilla war against the country's regime for the past seven years, control most of the countryside. Even in the national parliament, the second largest party happens to be the Communist Party of Nepal (United Marxist- Leninist). So, irrespective of whether one applies the criterion of parliamentary or extra-parliamentary influence, Marxists, and not revanchists of the Togadia-Singhal brand, reflect the overwhelming vox populi in Nepal. This clinches several points. Not rapid religious sentiments, but hard economic realities, mould the psyche of a nation. If the chemistry is different in Aryavarta, that is because of an unnatural hiatus between people existing under today's canopy and their consciousness lagging millennia behind. -

139 4 - 10 April 2003 16 Pages Rs 25

www.nepalitimes.com #139 4 - 10 April 2003 16 pages Rs 25 Maoists, police and soldiers are rushing home MIN BAJRACHARYA ‘‘‘ to meet families while the Peace bridge peace lasts. in KALIKOT MANJUSHREE○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ THAPA athletes have joined a regional few weeks into the ceasefire, volleyball competition. A driver who and Dailekh bazar is trans- weekly plies the Nepalganj-Dailekh ’’’ Out in the open A formed. “Nobody dared to road says hundreds of people who had The Maoist negotiating team hasn’t had a move about like this before,” marvels a fled during the state of emergency are moment to spare as it made its high-profile young man, eyeing the bustle. “The returning. “The Maoists, the police comeback in Kathmandu this week. Maoists didn’t dare come here, and the and the army are rushing back to meet Baburam Bhattarai and Ram Bahadur their families while the peace lasts.” Thapa have been giving back-to-back security forces wouldn’t go to the interviews to media, meeting political villages alone. Now they’re all talking Further afield in Dullu, the scene is leaders and diplomats and reiterating their to one another.” even more festive. Many village men three-point demand for a roundtable A few Maoists are openly attending are stoned on the occasion of Holi, in conference, constituent assembly and an passing-out ceremonies in local schools. flagrant defiance of Maoist puritanism. interim government. A rally in Tundikhel In nearby Chupra village, Maoist “We welcome the talks,” says Maoist on Thursday, two months after the ceasefire agreement, was attended by about 15- area secretary, ‘Rebel’, talking to us at a 20,000 supporters, mainly from outside the hotel close to where a man, high on Valley. -

Reacting to Donald Trump's Challenge

centro studi per i popoli extra-europei “cesare bonacossa” - università di pavia The Journal of the Italian think tank on Asia founded by Giorgio Borsa in 1989 Vol. XXIX / 2018 Reacting to Donald Trump’s Challenge Edited by Michelguglielmo Torri Nicola Mocci viella centro studi per i popoli extra-europei “cesare bonacossa” - università di pavia ASIA MAIOR The Journal of the Italian think tank on Asia founded by Giorgio Borsa in 1989 Vol. XXIX / 2018 Reacting to Donald Trump’s Challenge Edited by Michelguglielmo Torri and Nicola Mocci viella Asia Maior. The Journal of the Italian Think Tank on Asia founded by Giorgio Borsa in 1989. Copyright © 2019 - Viella s.r.l. & Associazione Asia Maior ISBN 978-88-3313-241-9 (Paper) ISBN 978-88-3313-242-6 (Online) ISSN 2385-2526 (Paper) ISSN 2612-6680 (Online) Annual journal - Vol. XXIX, 2018 This journal is published jointly by the think tank Asia Maior (Associazione Asia Maior) & CSPE - Centro Studi per i Popoli extra-europei «Cesare Bonacossa», University of Pavia Asia Maior. The Journal of the Italian Think Tank on Asia founded by Giorgio Borsa in 1989 is an open-access journal, whose issues and single articles can be freely downloaded from the think tank webpage: www.asiamaior.org. Paper version Italy € 50.00 Abroad € 65.00 Subscription [email protected] www.viella.it Editorial board Editor-in-chief (direttore responsabile): Michelguglielmo Torri, University of Turin. Co-editor: Nicola Mocci, University of Sassari. associate editors: Axel Berkofsky, University of Pavia; Diego Maiorano, National University of Singapore, ISAS - Institute of South Asian Studies; Nicola Mocci, University of Sassari; Giulio Pugliese, King’s College London; Michelguglielmo Torri, University of Turin; Elena Valdameri, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology - ETh Zurich; Pierluigi Valsecchi, University of Pavia. -

Ramechhap HRRP General Coordination Meeting,11Th Dec 2018

HRRP District Coordination Meeting Minutes Meeting Purpose: HRRP General Coordination Meeting Meeting Date: 11/12/2018 (11th Dec 2018) Meeting Time: 11am – 2pm Meeting Location: Devkota Chowk, Manthali DTO Meeting Hall, Ramechhap Meeting Facilitator: Prakash Bishwakarma Minutes Taken By: Prakash Bishwakarma / Javeed Mohamad Summary of Total: 16 Female:1 Male: 15 participants: Discussion: (Items/Knowledge Shared) GMaLi/HRRP Ramechhap General coordination meeting was chaired by Mr. Krishna lal Piya – GMALI Office Chief, Ramechhap and chief guest was Mr. Shanti prasad Paudel Provincial member of parliament province 3. Agenda: ➢ Welcome/Introduction ➢ Follow up of previous month’s meeting discussion and parking lot ➢ POs update – please share your update packs (PPT) so that can be shared in the meeting minute ➢ AOB Discussion ➢ Welcome and Introduction: Mr. Prakash Bishwakarma- District Coordinator- HRRP welcomed all the participants participated in the General coordination meeting and had a round of the introduction with each other. He also shared the objective and agenda of the General coordination meeting to be discussed in the meeting. ➢ HRRP updates: Mr. Prakash Bishwakarma- District coordinator have a presentation on What HRRP is doing and What HRRP is? Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform (HRRP) is working in Nepal to support Government of Nepal (NRA, MOUD/DUDBC, MOFALD) in coordination, Strategic planning, facilitating cooperation with the national and international organizations, the private sector, and public associations involve in recovery and reconstruction after Earthquake in Nepal. In the following ways HRRP Work. -General Coordination -Technical Coordination -Information Management o Collecting 5w data o Manage Training Database o Generate Maps ➢ Partners Update In Ramechhap District there are 6 partner’s organization are actively working in the district based on the reporting to GMALI/HRRP. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Psychosocial Intervention for Earthquake Survivors

PSYCHOSOCIAL INTERVENTION FOR EARTHQUAKE SURVIVORS FINAL REPORT JANUARY 2017 PSYCHOSOCIAL INTERVENTION FOR EARTHQUAKE SURVIVORS Duration June 2015 to December 2016 FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The 2015 earthquakes caused huge losses across 14 hill districts of Nepal. CMC-Nepal subsequently provided psychosocial and mental health support to affected people with funding from more than eight partners. The Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) supported a major emergency mental health and psychosocial response project in Dolakha, Ramechhap and Okhaldhunga districts from June 2015 to December 2016. I would first like to thank the project team for their hard work, dedication and many contributions. The success of the project is because of their hard work and motivation to learn. I thank the psychosocial counsellors and community psychosocial worker (CPSWs) for their dedication to serving the earthquake survivors. They developed their skills and provided psychosocial services to many distressed people. I congratulate them for successfully completing their training on psychosocial counselling (for counsellors) and psychosocial support (for CPSWs) and for their courage to provide support to their clients amidst difficult circumstances. I also thank the Project’s Supervisors (Karuna Kunwar, Madhu Bilash Khanal, Jyotshna Shrestha and Sujita Baniya), and Monitoring Supervisor (Himal Gaire) for their valuable constant backstopping support to the district staff. I thank Dorothee Janssen de Bisthoven (Expat Psychologist and Supervisor) for her help to build the capacity and maintain the morale of the project’s supervisors. Dorothee made a large contribution to building the capacity of the personnel and I express my gratitude and respect for her commitment and support to CMC-N and hope we can receive her support in the future as well. -

Map of Dolakha District Show Ing Proposed Vdcs for Survey

Annex 3.6 Annex 3.6 Map of Dolakha district showing proposed VDCs for survey Source: NARMA Inception Report A - 53 Annex 3.7 Annex 3.7 Summary of Periodic District Development Plans Outlay Districts Period Vision Objectives Priorities (Rs in 'ooo) Kavrepalanchok 2000/01- Protection of natural Qualitative change in social condition (i) Development of physical 7,021,441 2006/07 resources, health, of people in general and backward class infrastructure; education; (ii) Children education, agriculture (children, women, Dalit, neglected and and women; (iii) Agriculture; (iv) and tourism down trodden) and remote area people Natural heritage; (v) Health services; development in particular; Increase in agricultural (vi) Institutional development and and industrial production; Tourism and development management; (vii) infrastructure development; Proper Tourism; (viii) Industrial management and utilization of natural development; (ix) Development of resources. backward class and region; (x) Sports and culture Sindhuli Mahottari Ramechhap 2000/01 – Sustainable social, Integrated development in (i) Physical infrastructure (road, 2,131,888 2006/07 economic and socio-economic aspects; Overall electricity, communication), sustainable development of district by mobilizing alternative energy, residence and town development (Able, local resources; Development of human development, industry, mining and Prosperous and resources and information system; tourism; (ii) Education, culture and Civilized Capacity enhancement of local bodies sports; (III) Drinking -

![NEPAL: Gorkha - Operational Presence Map [As of 14 July 2015]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2101/nepal-gorkha-operational-presence-map-as-of-14-july-2015-1052101.webp)

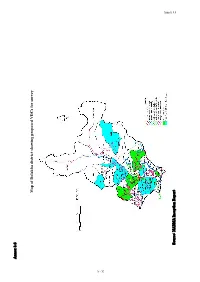

NEPAL: Gorkha - Operational Presence Map [As of 14 July 2015]

NEPAL: Gorkha - Operational Presence Map [as of 14 July 2015] 60 Samagaun Partners working in Gorkha Chhekampar 1-10 11-15 16-20 21-25 26-35 Lho Bihi Prok Chunchet Partners working in Nepal Sirdibas Health 26 Keroja Shelter and NFI Uhiya 23 Ghyachok Laprak WASH 18 Kharibot Warpak Gumda Kashigaun Protection 13 Lapu HansapurSimjung Muchchok Manbu Kerabari Sairpani Thumo Early Recovery 6 Jaubari Swara Thalajung Aaruaarbad Harmi ShrithankotTar k u k ot Amppipal ArupokhariAruchanaute Education 5 Palungtar Chhoprak Masel Tandrang Khoplang Tap le Gaikhur Dhawa Virkot PhinamAsrang Nutrition 1 Chyangling Borlang Bungkot Prithbinarayan Municipality Namjung DhuwakotDeurali Bakrang GhairungTan gli ch ok Tak lu ng Phujel Manakamana Makaising Darbung Mumlichok Ghyalchok IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS BY CLUSTER Early Recovery Education Health 6 partners 5 partners 26 partners Nb of Nb of Nb of organisations organisations organisations 1 >=5 1 >=5 1 >=5 Nutrition Protection Shelter and NFI 1 partners 13 partners 23 partners Nb of Nb of Nb of organisations organisations organisations 1 >=5 1 >=5 1 >=5 WASH 18 partners Want to find out the latest 3W products and other info on Nepal Earthquake response? visit the Humanitarian Response website at http:www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/op Nb of Note: organisations Implementing partners represent the organization on the ground, erations/nepal in the affected district doing operational work, such as send feedback to 1 >=5 distributing food, tents, water purification kits etc. [email protected] Creation date:23 July 2015 Glide number: EQ-2015-000048-NPL Sources: Cluster reporting The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

The Chantyal Language1 Michael Noonan University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CrossAsia-Repository The Chantyal Language1 Michael Noonan University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee 1. introduction The Chantyal language is spoken by approximately 2000 of the 10,000 ethnic Chantyal. The Chantyal live in the Baglung and Myagdi Districts of Nepal; the villages where the Chantyal language is spoken are all located in the eastern portion of the Myagdi District and include the villages of Mangale Kh‚ni, Dw‚ri, Ghy“s Khark‚, Caura Kh‚ni, Kuine Kh‚ni, Th‚r‚ Kh‚ni, P‚tle Khark‚, M‚l‚mp‚h‚r, and Malk‚b‚ng. There is relatively little linguistic variation among these villages, though where differences exist, it is the speech of Mangale Kh‚ni that is represented here. The Chantyal language is a member of the Tamangic group [along with Gurung, Thakali, Nar-Phu and Tamang, the last two of which are discussed in this volume]. Within the group, it is lexically and grammatically closest to Thakali. Assessment of the internal relations within the group is complicated by a number of factors, among which is the fact that shared innovations may be the product of geographic contiguity as much as shared genetic background. At the moment, the most likely classification is as fol- lows: Tamangic Tamang complex Gurungic Manangba—Nar-Phu complex Gurung Thakali—Chantyal Thakali Chantyal Chantyal, however, is in many respects the most deviant member of the group, lacking a tone system and having borrowed a large portion of its lexicon from Nepali. -

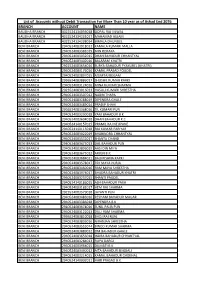

Branch Account Name

List of Accounts without Debit Transaction For More Than 10 year as of Ashad End 2076 BRANCH ACCOUNT NAME BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134056018 GOPAL RAJ SILWAL BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134231017 MAHAMAD ASLAM BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134298014 BIMALA DHUNGEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083918012 KAMALA KUMARI MALLA BENI BRANCH 2940524083381019 MIN ROKAYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083932015 DHAN BAHADUR CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083402016 BALARAM KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2922524083654016 SURYA BAHADUR PYAKUREL (KHATRI) BENI BRANCH 2940524083176016 KAMAL PRASAD POUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083897015 MUMTAJ BEGAM BENI BRANCH 2936524083886017 SHUSHIL KUMAR KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083124016 MINA KUMARI SHARMA BENI BRANCH 2923524083016013 HASULI KUMARI SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083507012 NABIN THAPA BENI BRANCH 2940524083288019 DIPENDRA GHALE BENI BRANCH 2940524083489014 PRADIP SHAHI BENI BRANCH 2936524083368016 TIL KUMARI PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083230018 YAM BAHADUR B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083604018 DHAN BAHADUR K.C BENI BRANCH 2940524140157015 PRAMIL RAJ NEUPANE BENI BRANCH 2940524140115018 RAJ KUMAR PARIYAR BENI BRANCH 2940524083022019 BHABINDRA CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083532017 SHANTA CHAND BENI BRANCH 2940524083475013 DAL BAHADUR PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083896019 AASI DIN MIYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083675012 ARJUN B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083684011 BALKRISHNA KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083578017 TEK MAYA PURJA BENI BRANCH 2940524083460016 RAM MAYA SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083974017 BHADRA BAHADUR KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2940524083237015 SHANTI PAUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524140186015 -

Mainstream Religious Domain in Nepal a Contradiction and Conflict

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Electronic Sumy State University Institutional Repository SocioEconomic Challenges, Volume 3, Issue 1, 2019 ISSN (print) – 2520-6621, ISSN (online) – 2520-6214 Mainstream Religious Domain in Nepal a Contradiction and Conflict of Indigenous Communities in Maintaining the Identity, Race, Gender and Class https://doi.org/10.21272/sec.3(1).99-115.2019 Medani P. Bhandari PhD, Professor and Deputy Program Director of Sustainability Studies, Akamai University, Hawaii, USA, Professor of Economics and Entrepreneurships, Sumy State University, Ukraine Nepal is certainly one of the more romanticized places on earth, with its towering Himalayas, its abomi- nable snowmen, and its musically named capital, Kathmandu, a symbol of all those faraway places the imperial imagination dreamt about. And the Sherpa people ... are perhaps one of the more romanticized people of the world, renowned for their mountaineering feats, and found congeal by Westerners tour their warm, friendly, strong, self-confident style" (Sherry Ortner, 1978: 10). “All Nepalese, whether they realize it or not, are immensely sophisticated in their knowledge and appreciation cultural differences. It is a rare Nepalese indeed who knows how to speak only one language” (James Fisher 1987:33). Abstract Nepal is unique in terms of culture, religion, and geography as well as in its Indigenous Communities (IC). There has always been domination by the mainstream culture and religion; however, until recently there was no visible friction and violence between any religious groups and ICs. Within the societal structure, there was an effort to maintain harmonious relationships, at least on the surface.