University Microfilms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sonderausgabe WANDERN PREMIUMWANDERN SCHWÄBISCHER WALD

MIT DEN Sonderausgabe WANDERN PREMIUMWANDERN SCHWÄBISCHER WALD »Aktiv im « SCHWÄBISCHER WANDERLAND DIE GÄSTEZEITSCHRIFT FÜR DIE FREIZEIT- UND ERHOLUNGSREGION SCHWÄBISCHERWALD WALD Sonderausgabe 2020 | Herausgegeben von Schwäbischer Wald Tourismus e.V. Premiumwandern im Wanderland Schwäbischer Wald Im einzigartigen Lebensraum des Schwäbischen Waldes gibt es vieles zu entdecken, was Natur oder Kultur – oder beide gemein- sam – hervorgebracht haben. Lichtdurchflutete Streuobstwiesen Der Schwäbische Wald und dunkle Wälder mit tiefen Schluchten und geheimnisvollen ist Partner der Klingen lassen sich ebenso erwandern wie kultivierte Weinberge. Relikte aus der Römerzeit reihen sich entlang dem Obergerma- nischen Limes wie an einer Perlenschnur auf. Er durchquert den Schwäbischen Wald und ist offizielles UNESCO Welterbe. Neben liebevoll unterhaltenen Heimat-, Natur- oder Sondermuseen laden alte Mühlen mit teilweise funktionstüchtiger Technik und Freizeit- und Erlebniszentren auf einen Besuch ein. Auf den folgenden Seiten stellen wir Ihnen ausgesuchte Wander- wege vor, die Lust auf den Schwäbischen Wald machen. All diese wunderbaren Wege sind nach dem Wanderleitsystem des Natur- parks Schwäbisch-Fränkischer Wald ausgeschildert und werden in umfangreichen Karten der jeweiligen Kommunen präsentiert. Wir wünschen Ihnen viel Spaß bei „wanderbaren“ Ausflügen ins Naturrefugium Schwäbischer Wald. Ihr Redaktionsteam Impressum Herausgeber: Schwäbischer Wald Tourismus e.V., Alter Postplatz 10, 71332 Waiblingen, Telefon 07151-501-1376, E-Mail → [email protected], -

Landeszentrale Für Politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, Director: Lothar Frick 6Th Fully Revised Edition, Stuttgart 2008

BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG A Portrait of the German Southwest 6th fully revised edition 2008 Publishing details Reinhold Weber and Iris Häuser (editors): Baden-Württemberg – A Portrait of the German Southwest, published by the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, Director: Lothar Frick 6th fully revised edition, Stuttgart 2008. Stafflenbergstraße 38 Co-authors: 70184 Stuttgart Hans-Georg Wehling www.lpb-bw.de Dorothea Urban Please send orders to: Konrad Pflug Fax: +49 (0)711 / 164099-77 Oliver Turecek [email protected] Editorial deadline: 1 July, 2008 Design: Studio für Mediendesign, Rottenburg am Neckar, Many thanks to: www.8421medien.de Printed by: PFITZER Druck und Medien e. K., Renningen, www.pfitzer.de Landesvermessungsamt Title photo: Manfred Grohe, Kirchentellinsfurt Baden-Württemberg Translation: proverb oHG, Stuttgart, www.proverb.de EDITORIAL Baden-Württemberg is an international state – The publication is intended for a broad pub- in many respects: it has mutual political, lic: schoolchildren, trainees and students, em- economic and cultural ties to various regions ployed persons, people involved in society and around the world. Millions of guests visit our politics, visitors and guests to our state – in state every year – schoolchildren, students, short, for anyone interested in Baden-Würt- businessmen, scientists, journalists and numer- temberg looking for concise, reliable informa- ous tourists. A key job of the State Agency for tion on the southwest of Germany. Civic Education (Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, LpB) is to inform Our thanks go out to everyone who has made people about the history of as well as the poli- a special contribution to ensuring that this tics and society in Baden-Württemberg. -

Montag Bis Freitag

DB Regio AG Crailsheim - Stuttgart Hbf Fahrplan 2008 Regionalverkehr Württemberg Gültig ab 10. März 2008 Angebotsplanung 785 Montag bis Freitag RE RE RE RE RE RE RE RE RE RE 19900 19910 19904 19976 19932 19940 19948 19958 19962 19968 Nürn- Nürn- Nürn- Nürn- Von: Ansbach Ansbach Ansbach berg berg berg berg Crailsheim an 9:41 11:41 13:43 15:41 17:41 19:41 21:41 Crailsheim ab 4:52 5:56 6:35 9:42 11:42 13:43 15:43 17:43 19:42 21:42 Eckartshausen-Ilshofen 5:00 6:04 6:43 9:50 11:50 13:51 15:51 17:51 19:50 21:50 Schw H-Hessental an 5:10 6:14 6:53 10:00 12:00 14:00 16:01 18:01 20:00 22:00 Schw H-Hessental ab 5:11 6:18 6:54 10:03 12:03 14:03 16:03 18:06 20:03 22:03 Gaildorf West 5:20 6:28 7:03 10:11 12:11 14:11 16:11 18:14 20:11 22:11 Fichtenberg 5:25 6:38 7:08 10:16 12:16 14:16 16:16 18:19 20:16 22:16 Fornsbach 5:29 6:42 7:12 10:20 12:20 14:20 16:20 18:23 20:20 22:20 Murrhardt an 5:33 6:46 7:16 10:24 12:24 14:24 16:24 18:27 20:24 22:24 Murrhardt ab 5:34 6:47 7:17 10:35 12:35 14:35 16:29 18:35 20:25 22:25 Sulzbach (Murr) 5:40 6:52 7:22 10:40 12:40 14:40 16:35 18:40 20:40 22:40 Oppenweiler (Wü) 5:44 6:57 7:26 10:44 12:44 14:44 16:44 18:44 20:44 22:44 Backnang an 5:50 7:03 7:32 10:50 12:50 14:50 16:50 18:50 20:50 22:50 Backnang ab 5:51 7:05 7:36 10:51 12:51 14:51 16:51 18:51 20:51 22:51 Winnenden 5:58 7:12 7:42 10:58 12:58 14:58 16:58 18:58 20:58 22:58 Waiblingen 6:06 7:21 7:51 11:06 13:06 15:06 17:06 19:06 21:06 23:06 Stg-Bad Cannst 6:14 7:31 7:58 11:14 13:14 15:14 17:14 19:14 21:14 23:14 Stuttgart Hbf an 6:18 7:35 8:03 11:18 13:18 15:18 17:18 19:18 21:18 23:18 Rot = Abweichung Trotz sorgfältiger Bearbeitung kann die Tabelle Fehler enthalten! 1 / 4 bw_kbs_785_stuttgart_crailsheim.xls DB Regio AG Crailsheim - Stuttgart Hbf Fahrplan 2008 Regionalverkehr Württemberg Gültig ab 10. -

Lebenserwartung in Den Kreisen: Bis Zu Drei Jahre Unterschied

Statistisches Monatsheft Baden-Württemberg 7/2004 Titelthema Lebenserwartung in den Kreisen: bis zu drei Jahre Unterschied Hans-Martin von Gaudecker Was sind die Gründe für die zum Teil erstaun- Diese Studie entstand in enger Zusammenar- lich hohen Sterblichkeitsunterschiede in Baden- beit zwischen dem Mannheimer Forschungs- Württemberg auf Kreisebene? Mit dieser Frage institut Ökonomie und demografischer Wandel beschäftigt sich die diesem Text zugrunde lie- (MEA) und dem Statistischen Landesamt Baden- gende Studie. Es kann ausgeschlossen werden, Württemberg. Eine ausführliche Version ist er- dass die Differenzen allein auf Zufallsschwan- schienen in der Reihe Statistische Analysen, kungen oder Fehlern im Meldewesen beruhen. Regionale Mortalitätsunterschiede, herausge- Eine Ursachenanalyse zeigt, dass Haupterklä- geben vom Statistischen Landesamt Baden- rungsgrund für die Sterblichkeitsunterschiede Württemberg. Diplom-Volkswirt Hans- der sozioökonomische Status ist: In Kreisen Martin von Gaudecker ist mit hohem Einkommen leben die Menschen Mitarbeiter am Mann- heimer Forschungs- im Durchschnitt länger als in Kreisen mit ge- Lebenserwartung in Baden-Württemberg institut Ökonomie und ringem Einkommen. Der Einfluss des sozioöko- demografischer Wandel (MEA) sowie Stipendiat nomischen Status auf die Mortalität scheint Die Lebenserwartung der Baden-Württemberger am Zentrum für wirt- durch höhere Bildung verstärkt oder sogar ver- lag im Jahr 2001 mit 77 Jahren für neugeborene schaftswissenschaftliche Doktorandenstudien ursacht zu werden. Luftbelastung -

6 X 10.5 Three Line Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-76020-1 - The Negotiated Reformation: Imperial Cities and the Politics of Urban Reform, 1525-1550 Christopher W. Close Index More information Index Aalen, 26n20 consultation with Donauworth,¨ 37, Abray, Lorna Jane, 6 111–114, 116–119, 135–139, Aitinger, Sebastian, 75n71 211–214, 228, 254 Alber, Matthaus,¨ 54, 54n120, 54n123 consultation with Kaufbeuren, 41, 149, Albrecht, Archbishop of Mainz, 255 157–159, 174–176, 214, 250, 254 Altenbaindt, 188n33 consultation with Kempten, 167–168, Anabaptist Mandate, 156n42 249 Anabaptists, 143, 151, 153, 155 consultation with Memmingen, 32, 50, association with spiritualism, 156 51n109, 58, 167–168, 175 in Augsburg, 147, 148n12, 149, consultation with Nuremberg, 65, 68, 149n18 102, 104–108, 212–214, 250, 251 in Kaufbeuren, 17, 146–150, 148n13, consultation with Strasbourg, 95, 102, 154, 158, 161, 163, 167, 170, 214, 104–106, 251 232, 250, 253 consultation with Ulm, 33, 65, 68, in Munster,¨ 150, 161 73–76, 102, 104–108, 167, 189, Augsburg, 2, 11–12, 17, 23, 27, 38, 42, 192–193, 195–196, 204–205, 208, 45–46, 90, 95, 98, 151, 257 211–214, 250, 254 abolition of the Mass, 69, 101, controversy over Mathias Espenmuller,¨ 226n63 174–177, 250 admission to Schmalkaldic League, 71, economic influence in Burgau, 184 73–76 end of reform in Mindelaltheim, alliance with Donauworth,¨ 139–143, 203–208 163, 213, 220 Eucharistic practice, 121 Anabaptist community, 147, 149 fear of invasion, 77, 103n80 April 1545 delegation to Kaufbeuren, Four Cities’ delegation, 144–146, 160–167 167–172, -

RZ Radlkarte Stand 05

Westallgäuer Käsestraße Auf der über 130 km langen Route liegen 17 Sennereien, in denen man sich über die Entstehung der traditionellen Allgäuer Käsesorten informieren und die Delikatessen auch versuchen kann. Touristikverband Lindau-Westallgäu, Stiftsplatz 4, 88131 Lindau ern-Radwanderwege Tel. 0 83 82/27 01 36, [email protected] F www.westallgaeuer-kaesestrasse.de oder www.lindau-westallgaeu.org Kneippradweg Auf den Spuren von Pfarrer Kneipp, durch die sanfte Wiesenlandschaft des Kneipplandes Unterallgäu, verbindet dieser Radweg die Kneippkurorte Bad Wörishofen, Bad Grönenbach und Ottobeuren. Kurverwaltung Bad Grönenbach, Marktplatz 5, 87730 Bad Grönenbach Tel. 0 83 34/6 05 31, Fax 0 83 34/61 33 www.bad-groenenbach.de, [email protected] und Kurverwaltung Bad Wörishofen, Luitpold-Leusser-Platz 2, 86825 Bad Wörishofen Tel. 0 82 47/99 33 55, Fax 0 82 47/99 33 59 www.bad-woerishofen.de, [email protected] 7-Schwaben-Tour Von Augsburg aus führt dieser ca. 220 Kilometer lange Radweg rund um den Naturpark Augsburg Westliche Wälder und erschließt eine abwechslungs- Bodensee-Königssee- reiche Hügellandschaft voller Sehenswürdigkeiten. Radweg Naturpark Augsburg-Westliche Wälder e.V., Fuggerstraße 10, 86830 Schwabmünchen Von Lindau am Bodensee führt der Weg durch Tel. 08 21/3 10 22 78, www.naturpark-augsburg.de die Landschaft des hügeligen Allgäuer Voralpen- landes. Vorbei am großen Alpsee, am Rottach- Stausee und Hopfensee wird Füssen erreicht. Hier verlässt er das Allgäu und führt weiter bis Radwanderweg Allgäu nach Berchtesgaden am Königssee. Gesamte Mit einem Abstecher zum Schwäbischen Bauernhofmuseum in Illerbeuren Streckenlänge: 399 km. erschließt der Allgäu-Radwanderweg die herrliche Allgäuer Voralpenland- ARGE Bodensee-Königssee-Radweg schaft zwischen Altusried und Weitnau, Kempten und Isny in einem abwechs- c/o Tourismusverb. -

PRESS RELEASE Heilbronn District in Germany Opts for Hydrogen

ul. Obornicka 46 , Bolechowo-Osiedle 62-005 Owińska Tel.: +48 61 66 72 333 Fax: +48 61 66 72 310 [email protected], www.solarisbus.com PRESS RELEASE Heilbronn district in Germany opts for hydrogen Bolechowo / Heilbronn, 02.07.2021 Solaris presented a hydrogen-powered bus, the Urbino 12 hydrogen in Neuenstadt am Kocher, Germany. Omnibus-Verkehr Ruoff GmbH (OVR), part of the Transdev Group, that manages public transport in the city set its hopes on innovation and is planning to use “green hydrogen” produced in an environmentally friendly way to fuel public transport. It is an opportunity for the operator (Omnibus-Verkehr Ruoff GmbH (OVR)) which is part of the Transdev Group to become a pioneer of zero-emission public transport in the Heilbron region. Hydrogen is to be produced in an environmentally friendly way within the “H2 Impulse” project and then used as zero-emission fuel for fuelling urban buses. The regional component is a decisive factor in the project: hydrogen is produced using wind energy in the German Aviation and Space Hub (DLR), situated in nearby Hardthäuser Wald. Then it is either used locally or transmitted to regional users, i.e. in Neuenstadt. Therefore the environmental balance of harmful emissions from production through the end user is close to zero. Within the project at the invitation of OVR Solaris presented an innovative bus, the Urbino 12 hydrogen, to project participants representing the County of Heilbronn, the city of Neustadt am Kocher, the municipalities of Hardthausen, Langenbrettach and Wirtschaftsfördergesellschaft Raum Heilbronn (WfG, an industrial development agency operating in the Heilbronn region). -

Forschung Und Entwicklung Teil 3: Regionale Fue-Ressourcen in Baden-Württemberg

Statistisches Monatsheft Baden-Württemberg 4/2020 Wirtschaft, Arbeitsmarkt Forschung und Entwicklung Teil 3: Regionale FuE-Ressourcen in Baden-Württemberg Ruth Einwiller Im dritten Beitrag der Veröffentlichungsreihe Böblingen und Heidelberg mit zum Thema „Forschung und Entwicklung höchster FuE-Personalintensität (FuE)“ wird die Verteilung der FuE-Ressour- cen in den Kreisen und Regionen im Süd- Gemessen am Forschungspersonal und an westen betrachtet. den Forschungsinvestitionen (i-Punkt: „FuE Kennzahlen“) ist die Region Stuttgart mit wei- Der Südwesten hat innerhalb Deutschlands tem Abstand der bedeutendste Forschungs- die höchsten FuE-Ressourcen. Diese sind in standort. Über 40 % des landesweiten FuE- Baden-Württemberg auf die einzelnen Sek- Personals im Staats-, Hochschul- und Wirt- Dipl.-Volkswirtin Ruth toren und auch regional sehr unterschiedlich schaftssektor (i-Punkt: „Sektoren“) ist hier Einwiller ist Referentin im Referat „Wirtschaftswissen- verteilt. Der Wirtschaftssektor ist hierzulande tätig bzw. fast die Hälfte der FuE-Ausgaben schaftliche Analysen, Arbeits- mit 84 % der bedeutendste Forschungsträger. fallen hier an. Neben der Region Stuttgart markt, Außenhandel“ des Statistischen Landesamtes Der Anteil des Staatssektors und des Hoch- zählen auch die Regionen Rhein-Neckar, Mitt- Baden-Württemberg. schulsektors lag im Jahr 2017 bei 7 % bzw. lerer Oberrhein und Heilbronn-Franken zu den 9 %. Bei der nachfolgenden regionalen Ana- FuE-Standorten mit hohen FuE-Ressourcen. In lyse der FuE-Ressourcen wird vorrangig der diesen vier Regionen waren 2017 insgesamt Wirtschaftssektor untersucht. Die FuE-Res- über zwei Drittel des landesweiten FuE-Per- sourcen unterliegen im Staatssektor auf regi- sonals eingesetzt. Der Anteil des FuE-Per- onaler Ebene aus datenschutzrechtlichen und sonals in den Stadtkreisen Stuttgart und Hei- im Hochschulsektor auf Kreisebene aus me- delberg sowie in den Landkreisen Böblingen, thodischen Gründen der Geheimhaltung. -

RB87/RB89 Aalen – Nördlingen – Donauwörth 2. Juni 6. Juni Bis 1

RB87/RB89 Aalen – Nördlingen – Donauwörth 2. Juni 6. Juni bis 1. Juli Schienenersatzverkehr Fahrplanänderungen 1. Berichtigung Regio Bayern Erläuterungen zum SEV-Symbol Bei einem Schienenersatzverkehr sind Ihnen diese beiden Symbole auf Bussen, Halte- stellen, Aushängen und als Bestandteil der Wegeleitung vom/zum Schienenersatzver- kehr behilflich. Bitte beachten Sie hierbei folgendes: Das untere Symbol wird schrittweise durch das obere (neue) Symbol ersetzt. Gültigkeit haben weiterhin beide Symbole. Farben und Kennzeichnungen in den Fahrplantabellen 6.48 frühere Abfahrt 6.48 spätere Abfahrt 6.48 Busabfahrt (SEV) 6.48 Fahrt kann später verkehren 6.48 Fahrt fällt aus 6.48 zusätzlicher Bus / Expressbus X 6.48 Zug hält nur bei Bedarf … Erläuterung siehe unter der Fahrplantabelle Zug bzw. Bus mit Fahrradbeförderung Zugvereinigung / Zugteilung beachten Max Maulwurf – Symbolfigur der Deutschen Bahn bei Bauarbeiten Seit 1994 informiert der kleine aktive Wühler über das aktuelle Bau- geschehen bei der Deutschen Bahn und wirbt auf seine unnachahm- liche Weise um Verständnis. Mehr über Max Maulwurf erfahren Sie auf www.deutschebahn.com/maxmaulwurf (mit Links zur Max- Fanseite und zu Max-Maulwurf-Artikeln im Bahnshop). Informationsmöglichkeiten Sonderbroschüre auf großen Bahnhöfen an der DB Information sowie in DB Reisezentren und Verkaufsstellen Aushänge auf den Stationen Internet bauinfos.deutschebahn.com mit Newsletter und RSS-Feed Mobiltelefon bauinfos.deutschebahn.com/mobile Videotext BAYERNTEXT Tafel 700 Aktuelle Betriebslage bahn.de/ris oder für Mobiltelefone m.bahn.de/ris Die Service-Nummer der Bahn Telefon 0180 6 99 66 33 (20 ct/Anruf aus dem Festnetz, Tarif bei Mobilfunk max. 60 ct/Anruf) Kundendialog Nahverkehr Lob, Kritik, Anregungen oder Fragen zu den Fahrgastrechten Telefon 089 2035 5000 E-Mail [email protected] Bei baubedingten Fahrplanänderungen werden Sie kostenlos und ohne Werbung per E-Mail benachrichtigt. -

Aalen International Program

01 AALEN HIER STEHT DAS THEMA DER SEITE INTERNATIONAL Program INFORMATION FOR PARTNER UNIVERSITIES AND EXCHANGE STUDENTS www e at .aa m le d n a -u lo n i n v w e ACADEMIC r o s D i t y . d YEAR e 2021-2022 TWO NEW RESEARCH 02BUILDINGS WERE 03 INAUGURATED ON AALEN HIER STEHT DAS THEMACONTENTS DER SEITE UNIVERSITY CAMPUS IN 2020 06 12 26 30 Become Part of Our Program - Application Services for Aalen University Your Chance Process International Students Become Part of Aalen University 06 Start Here, Go Anywhere 24 In the Heart of the South 08 From Cameroon to Aalen 25 The Economic Center of the South 10 Our Easy Application Process 26 Our Program - Your Chance 12 You Need More Help? 28 Teaching and Learning 14 From Portugal to Aalen 29 What you Need to Know 18 Service for International Students 30 Internships: A Golden Opportunity 20 Accomodation 32 From Costa Rica to Aalen 21 Campus Life 34 From India to Aalen 22 City Life 36 Hands on: Upgrade to Platinum 23 Facts & Figures 38 EDITION NOTE FOR FIFTH EDITION, FEB 2021 Publisher: Aalen University, Beethovenstraße 1, 73430 Aalen, Germany Contact: hs-aalen.de, Email: [email protected] Edition: 1.000 pcs. Photos: Aalen University, City of Aalen, Stadtwerke Aalen (public utility companies), Christian Frumolt, Reiner Pfisterer, Jan Walford, Sandro Bretzger, Janine Soika, Thomas Klink, Peter Schlipf, Juana Röder (Freistil Design), International Center, Carolin Fischer, Jana Ling Design: Freistil Design GbR, frei-stil-design.de 04 05 HIER STEHT DAS THEMA DER SEITE HIER STEHT DAS THEMA DER SEITE Welcome to Aalen VARIETY IS THE SPICE OF LIFE - TOGETHER FOR INTERNATIONAL FRIENDSHIP 06 07 STUDYING IN AALEN STUDYING IN AALEN one of the most research-intensive universities of Technology, Photonics, Casting Technology, Business applied sciences in Germany. -

Mitteilungsblatt KW 03/21

Mitteilungsblatt der Gemeinde Balzheim NEUIGKEITEN AUS OBER- UND UNTERBALZHEIM Freitag, 22. Januar 2021/Nr. 03 AMTLICHE BEKANNTMACHUNGEN Termine Diese Bündelung der 55 einzelnen Kom- Corona-Verordnung 22.01.2021 Abfuhr Gelber Sack Einreise-Quarantäne munen stärkt die fachliche Kompetenz im Bereich der Grundstücksbewertung, ermöglicht eine qualifiziertere Marktbe- Zum 18.01.2021 ist eine erneute Ände- 23.01.2021 Recyclinghof wertung und lässt eine rechtssichere rung der CoronaVO EQ in Kraft getreten. Carl-Otto-Weg 16 Ableitung der Bodenrichtwerte zu. Diese neue Verordnung regelt die Quaran- 10.30 – 12.00 Uhr täne. Die Testpflicht (2 Stufen Testung) wird nun einheitlich über die Bundesver- Auch die Gemeinde Balzheim gehört diesem Gremium an. Der lokale Gutachter- ordnung geregelt. 25.01.2021 Gemeinde Balzheim ausschuss beendete seine Tätigkeiten Gemeinderatssitzung mit zum 31. Januar 2021. Ab dem 01. Februar Bei Einreise aus einem Risikogebiet Einsetzung und 2021 wird der gemeinsame Gutachteraus- besteht weiterhin grundsätzlich eine Verpflichtung des neuen schuss dessen Aufgaben übernehmen. zehntägige Quarantänepflicht, die frühe- Bürgermeisters stens mit einem ab dem fünften Tag der Herrn Maximilian Die Führung einer Kaufpreissammlung, die Quarantäne erhobenen negativen Tester- Hartleitner, Ermittlung von Bodenrichtwerten, die gebnis beendet werden kann. Es gilt zu- Dorfgemeinschaftshaus, Erstattung von Gutachten, die Erteilung sätzlich eine Testpflicht bei Einreise. großer Saal, 18:00 Uhr von Auskünften und weitere Verwaltungs- Der Testpflicht kann durch eine Testung Hinweis: Zugang nur für aufgaben, wie diese im Baugesetzbuch binnen 48 Stunden vor Anreise oder durch geladene Personen eine Testung unmittelbar nach Einreise geregelt sind, werden künftig über den nachgekommen werden. gemeinsamen Gutachterausschuss abge- wickelt. 29.01.2021 Recyclinghof Bitte wenden Sie sich in diesen Fällen an Von einer Coronavirus-Infektion „Gene- Carl-Otto-Weg 16 die dortige Geschäftsstelle: sene“ sind von der Quarantänepflicht be- 15:00 – 16:30 freit. -

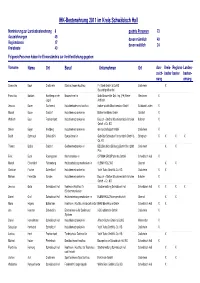

Pressemitteilung SHA Anlage.Pdf

IHK-Bestenehrung 2011 im Kreis Schwäbisch Hall Nominierung zur Landesbestenehrung 8 geehrte Personen 73 Auszeichnungen 49 davon männlich 49 Regionsbeste 17 davon weiblich 24 Kreisbeste 40 Folgende Personen haben ihr Einverständnis zur Veröffentlichung gegeben: Vorname Name Ort Beruf Unternehmen Ort Aus- Kreis- Regions- Landes- zeich- bester bester besten- nung ehrung SamanthaBach Crailsheim Bürokaufmann/-kauffrau Fr. Eberl GmbH & Co KG Crailsheim X Baustoffgroßhandel FranziskaBaldwin Kirchberg an der Bauzeichner/-in Bodo Braunmiller Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Freier Gerabronn X Jagst Architekt Jessica Bauer Gschwend Industriekaufmann/-kauffrau kocher-plastik Maschinenbau-GmbH Sulzbach-Laufen X Marcel Bauer Gaildorf Industriemechaniker/-in Mahle Ventiltrieb GmbH Gaildorf X Wolfram Baur Frankenhardt Industriemechaniker/-in Bausch + Ströbel Maschinenfabrik Ilshofen Ilshofen X GmbH + Co. KG Simon Bayer Kreßberg Industriemechaniker/-in Gerhard Schubert GmbH Crailsheim X David Bohnsack Dinkelsbühl Bauzeichner/-in Gebrüder Schneider Fensterfabrik GmbH & Stimpfach X X X X Co. KG Thiemo Bojbic Gaildorf Gießereimechaniker/-in BBQ Berufliche Bildung gGbmH Start 2000 Crailsheim X X Plus Felix Buck Rosengarten Mechatroniker/-in OPTIMA GROUP pharma GmbH Schwäbisch Hall X Marcel Ehrenfried Fichtenberg Holzbearbeitungsmechaniker/-in KLENK HOLZ AG Oberrot X X Christian Fischer Schnelldorf Industriemechaniker/-in Voith Turbo GmbH & Co. KG Crailsheim X X Michael Freimüller Ilshofen Industriemechaniker/-in Bausch + Ströbel Maschinenfabrik Ilshofen Ilshofen X GmbH +