Recognition and Rights of Indigenous Peoples Secondary Sources, and Learning Activities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOLONEC Shared Lives on Nigena Country

Shared lives on Nigena country: A joint Biography of Katie and Frank Rodriguez, 1944-1994. Jacinta Solonec 20131828 M.A. Edith Cowan University, 2003., B.A. Edith Cowan University, 1994 This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities (Discipline – History) 2015 Abstract On the 8th of December 1946 Katie Fraser and Frank Rodriguez married in the Holy Rosary Catholic Church in Derby, Western Australia. They spent the next forty-eight years together, living in the West Kimberley and making a home for themselves on Nigena country. These are Katie’s ancestral homelands, far from Frank’s birthplace in Galicia, Spain. This thesis offers an investigation into the social history of a West Kimberley couple and their family, a couple the likes of whom are rarely represented in the history books, who arguably typify the historic multiculturalism of the Kimberley community. Katie and Frank were seemingly ordinary people, who like many others at the time were socially and politically marginalised due to Katie being Aboriginal and Frank being a migrant from a non-English speaking background. Moreover in many respects their shared life experiences encapsulate the history of the Kimberley, and the experiences of many of its people who have been marginalised from history. Their lives were shaped by their shared faith and Katie’s family connections to the Catholic mission at Beagle Bay, the different governmental policies which sought to assimilate them into an Australian way of life, as well as their experiences working in the pastoral industry. -

March 2013 Issue No: 119 in This Issue Club Meetings Apologies Contact Us 1

March 2013 Issue No: 119 In this issue Club Meetings Apologies Contact us 1. Zontaring on 2. IWD o Second Thursday of the o By 12 noon previous [email protected] 3. Tricia – Life Member of Stadium www.zontaperth.org.au Snappers Master Swimming Club month (except January) Monday 4. ZCP Holiday Relief Scheme o 6.15pm for 6.45pm o [email protected] PO Box 237 5. Dr Sue Gordon o St Catherine’s College, Nedlands WA 6909 6. Fiona Crowe – Volunteer Fire UWA Fighter 7. Diary Dates 1. Zontaring on…. Larraine McLean, President Since the Inzert in November 2012 we have lost and achieved a great deal! We have suffered the loss of and saluted the efforts of Marg Giles. We held a wake in her honour at the Pioneers Memorial Garden in Kings Park; sent condolence letters and cards to her family; placed a notice in the West Australian Newspaper and produced a special edition of Inzert to commemorate her efforts. Marg was with us at our Christmas event in December. I sat at the same table as Larraine McLean, Marg and she seemed to be enjoying the fellowship and fun around her. Marg, as President always, participated in the Christmas Bring and Buy which was a huge success. Delicious Christmas fare was supplied by members that was quickly bought by other members, friends and guests. It is consoling that Marg’s last time with us seemed to be such a positive event for her. In January we heard of the death of Hariette Yeckel. -

The History of NAIDOC Celebrating Indigenous Culture

The History of NAIDOC Celebrating Indigenous Culture latrobe.edu.au CRICOS Provider 00115M Wominjeka Welcome La Trobe University 22 Acknowledgement La Trobe University acknowledges the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nations as the traditional custodians of the land upon which the Bundoora campus is located. LaLa Trobe Trobe University University 33 Acknowledgement We recognise their ongoing connection to the land and value the unique contribution the Wurundjeri people and all Indigenous Australians make to the University and the wider Australian society. LaLa Trobe Trobe University University 44 What is NAIDOC? NAIDOC stands for the ‘National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee’. This committee was responsible for organising national activities during NAIDOC Week and its acronym has since become the name of the week itself. La Trobe University 55 History of NAIDOC NAIDOC Week celebrations are held across Australia each July to celebrate the history, culture and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. NAIDOC is celebrated not only in Indigenous communities, but by Australians from all walks of life. La Trobe University 66 History of NAIDOC 1920-1930 Before the 1920s, Aboriginal rights groups boycotted Australia Day (26 January) in protest against the status and treatment of Indigenous Australians. Several organisations emerged to fill this role, particularly the Australian Aborigines Progressive Association (AAPA) in 1924 and the Australian Aborigines League (AAL) in 1932. La Trobe University 77 History of NAIDOC 1930’s In 1935, William Cooper, founder of the AAL, drafted a petition to send to King George V, asking for special Aboriginal electorates in Federal Parliament. The Australian Government believed that the petition fell outside its constitutional Responsibilities William Cooper (c. -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

Day of Mourning – Overview Fact Sheet

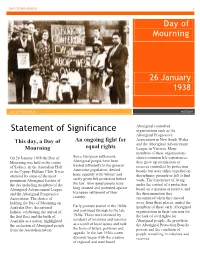

DAY OF MOURNING 1 Day of Mourning 26 January 1938 DAY OF MOURNING HISTORY Aboriginal controlled Statement of Significance organisations such as the Aboriginal Progressive Association in New South Wales An ongoing fight for This day, a Day of and the Aboriginal Advancement Mourning equal rights League in Victoria. Many members of these organisations On 26 January 1938 the Day of Since European settlement, shared common life experiences; Mourning was held in the centre Aboriginal people have been they grew up on missions or of Sydney, in the Australian Hall treated differently to the general reserves controlled by protection at the Cyprus Hellene Club. It was Australian population; denied boards but were either expelled on attended by some of the most basic equality with 'whites' and disciplinary grounds or left to find prominent Aboriginal leaders of rarely given full protection before work. The experience of living the day including members of the the law. Aboriginal people have under the control of a protection Aboriginal Advancement League long resisted and protested against board on a mission or reserve, and and the Aboriginal Progressive European settlement of their the discrimination they Association. The choice of country. encountered when they moved holding the Day of Mourning on away from these places, united the Australia Day, the national Early protests started in the 1840s members of these early Aboriginal holiday celebrating the arrival of and continued through to the late organisations in their concerns for the first fleet and the birth of 1920s. These were initiated by the lack of civil rights for Australia as a nation, highlighted residents of missions and reserves Aboriginal people, the growth in the exclusion of Aboriginal people as a result of local issues and took the Aboriginal Protection Board's from the Australian nation. -

Gladys Nicholls: an Urban Aboriginal Leader in Post-War Victoria

Gladys Nicholls: An Urban Aboriginal Leader in Post-war Victoria Patricia Grimshaw School of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC. 3010 [email protected] Abstract: Gladys Nicholls was an Aboriginal activist in mid-20 th century Victoria who made significant contributions to the development of support networks for the expanding urban Aboriginal community of inner-city Melbourne. She was a key member of a talented group of Indigenous Australians, including her husband Pastor Doug Nicholls, who worked at a local, state and national level to improve the economic wellbeing and civil rights of their people, including for the 1967 Referendum. Those who knew her remember her determined personality, her political intelligence and her unrelenting commitment to building a better future for Aboriginal people. Keywords: Aboriginal women, Aboriginal activism, Gladys Nicholls, Pastor Doug Nicholls, assimilation, Victorian Aborigines Advancement League, 1967 Referendum Gladys Nicholls (1906–1981) was an Indigenous leader who was significant from the 1940s to the 1970s, first, in action to improve conditions for Aboriginal people in Melbourne and second, in grassroots activism for Indigenous rights across Australia. When the Victorian government inscribed her name on the Victorian Women’s Honour Roll in 2008, the citation prepared by historian Richard Broome read as follows: ‘Lady Gladys Nicholls was an inspiration to Indigenous People, being a role model for young women, a leader in advocacy for the rights of Indigenous people as well as a tireless contributor to the community’. 1 Her leadership was marked by strong collaboration and co-operation with like-minded women and men, both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, who were at the forefront of Indigenous reform, including her prominent husband, Pastor (later Sir) Doug Nicholls. -

SEVEN WOMEN of the 1967 REFERENDUM Project For

SEVEN WOMEN OF THE 1967 REFERENDUM Project for Reconciliation Australia 2007 Dr Lenore Coltheart There are many stories worth repeating about the road to the Referendum that removed a handful of words from Australia’s Constitution in 1967. Here are the stories of seven women that tell how that road was made. INTRODUCING: SHIRLEY ANDREWS FAITH BANDLER MARY BENNETT ADA BROMHAM PEARL GIBBS OODGEROO NOONUCCAL JESSIE STREET Their stories reveal the prominence of Indigenous and non-Indigenous women around Australia in a campaign that started in kitchens and local community halls and stretched around the world. These are not stories of heroines - alongside each of those seven women were many other men and women just as closely involved. And all of those depended on hundreds of campaigners, who relied on thousands of supporters. In all, 80 000 people signed the petition that required Parliament to hold the Referendum. And on 27 May 1967, 5 183 113 Australians – 90.77% of the voters – made this the most successful Referendum in Australia’s history. These seven women would be the first to point out that it was not outstanding individuals, but everyday people working together that achieved this step to a more just Australia. Let them tell us how that happened – how they got involved, what they did, whether their hopes were realised – and why this is so important for us to know. 2 SHIRLEY ANDREWS 6 November 1915 - 15 September 2001 A dancer in the original Borovansky Ballet, a musician whose passion promoted an Australian folk music tradition, a campaigner for Aboriginal rights, and a biochemist - Shirley Andrews was a remarkable woman. -

Stretch Reconciliation Action Plan

Reconciliation Action Plan 2018 – 2020 Underwater Garden by Timeisha Simpson Timeisha Simpson is an emerging artist from Port Lincoln who has exhibited both on the West Coast and in Adelaide. She was studying in Year 9 when she created this work as part of Port Lincoln High School’s (PLHS) Aboriginal Arts Program. The PLHS Arts Program is an outlet for young artists to express themselves creatively. Local artist Jenny Silver has been working with the Arts Program for some time and has built strong relationships with all of the participating young artists. Many of the art works produced explore connections with culture, identity, family and place. It provides opportunities for the artists to be part of exhibitions across the state and their success at these exhibitions has created positive discussions with the wider community. An important aspect of the program is the emphasis on enterprise and the creation of individual artist portfolios. Jenny worked with Timeisha to create Underwater Garden, an acrylic painting that celebrates the richness and health of the water around Port Lincoln. Both artists spend a lot of time in the ocean and chose seaweed to represent growth and movement. Timeisha and Jenny developed authentic relationships with the community while on country which was integral in initial ideation for this piece. Timeisha says, ”The painting celebrates all the different bright coloured seaweeds in the ocean, I see these seaweeds when I go diving, snorkelling and fishing at the Port Lincoln National Park with my friends and family. I really enjoy going to Engine Point because that is where we go diving and snorkelling off the rocks, and for fishing we go to Salmon Hole and other cliff areas”. -

By-Elections in Western Australia

By-elections in Western Australia Contents WA By-elections - by date ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 WA By-elections - by reason ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 14 By-elections due to the death of a sitting member ........................................................................................................................................................... 14 Ministerial by-elections.................................................................................................................................................................................................... 16 Fresh election ordered ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 17 Seats declared vacant ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... 17 WA By-elections - by electorate .......................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Rare Books Lib

RBTH 2239 RARE BOOKS LIB. S The University of Sydney Copyright and use of this thesis This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copynght Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act gran~s the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author's moral rights if you: • fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work • attribute this thesis to another author • subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author's reputation For further information contact the University's Director of Copyright Services Telephone: 02 9351 2991 e-mail: [email protected] Camels, Ships and Trains: Translation Across the 'Indian Archipelago,' 1860- 1930 Samia Khatun A thesis submitted in fuUUment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History, University of Sydney March 2012 I Abstract In this thesis I pose the questions: What if historians of the Australian region began to read materials that are not in English? What places become visible beyond the territorial definitions of British settler colony and 'White Australia'? What past geographies could we reconstruct through historical prose? From the 1860s there emerged a circuit of camels, ships and trains connecting Australian deserts to the Indian Ocean world and British Indian ports. -

William Barak

WILLIAM BARAK A brief essay about William Barak drawn from the booklet William Barak - Bridge Builder of the Kulin by Gibb Wettenhall, and published by Aboriginal Affairs Victoria. Barak was educated at the Yarra Mission School in Narrm (Melbourne), and was a tracker in the Native Police before, as his father had done, becoming ngurungaeta (clan leader). Known as energetic, charismatic and mild mannered, he spent much of his life at Coranderrk Reserve, a self-sufficient Aboriginal farming community in Healesville. Barak campaigned to protect Coranderrk, worked to improve cross-cultural understanding and created many unique artworks and artefacts, leaving a rich cultural legacy for future generations. Leader William Barak was born into the Wurundjeri clan of the Woi wurung people in 1823, in the area now known as Croydon, in Melbourne. Originally named Beruk Barak, he adopted the name William after joining the Native Police as a 19 year old. Leadership was in Barak's blood: his father Bebejan was a ngurunggaeta (clan head) and his Uncle Billibellary, a signatory to John Batman's 1835 "treaty", became the Narrm (Melbourne) region's most senior elder. As a boy, Barak witnessed the signing of this document, which was to have grave and profound consequences for his people. Soon after white settlement a farming boom forced the Kulin peoples from their land, and many died of starvation and disease. During those hard years, Barak emerged as a politically savvy leader, skilled mediator and spokesman for his people. In partnership with his cousin Simon Wonga, a ngurunggaeta, Barak worked to establish and protect Coranderrk, a self- sufficient Aboriginal farming community in Healesville, and became a prominent figure in the struggle for Aboriginal rights and justice. -

Billibellary's

Billibellary’s Walk A cultural interpretation of the landscape that provides an experience of connection to country which Wurundjeri people continue to have, both physically and spiritually. Lying within the University of Melbourne’s built environment are the whispers and songs of the Wurundjeri people. As one of the clans of the Kulin Nation, the Wurundjeri people of the Woiwurrung language group walked the grounds upon which the University now stands for more than 40,000 years Stop 4 – Aboriginal Knowledge Stop 10 – Billibellary’s Country Aboriginal knowledge, bestowed through an oral tradition, is What would Billibellary think if he were to walk with you ever-evolving, enabling it to reflect its context. Sir Walter Baldwin now? The landscape has changed but while it looks Spencer, the University’s foundation professor of Biology in 1887, different on the surface Billibellary might remind you it still was highly esteemed for his anthropological and ethnographic holds the story of the Wurundjeri connection to Country work in Aboriginal communities but the Aboriginal community and our continuing traditions. today regards this work as a misappropriation of Aboriginal culture and knowledge. Artist: Kelly Koumalatsos, Wergaia/Wemba Wemba, Stop 5 – Self-determination and Community Control Possum Skin Cloak, Koorie Heritage Trust collection. Murrup Barak, Melbourne Indigenous Development Institute represents the fight that Billibellary, the Wurundjeri people, and Take a walk through Billibellary’s Country. indeed the whole Kulin nation were to face. The institute’s name Feel, know, imagine Melbourne’s six uses Woiwurung language to speak of the spirit of William Barak, seasons as they are subtly reconstructed Billibellary’s nephew and successor as Ngurungaeta to the as the context for understanding place and Wurundjeri Willam.