Gladys Nicholls: an Urban Aboriginal Leader in Post-War Victoria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RAA-Belonging Final Lores

BELONG aGREATARTSSTORIES ING FROM REGIONAL AUSTRALIAb written from conversations with aLindy ALLEN SNAPSHOTS based on interviews with aHélène SOBOLEWSKI edited by aMoya SAYER-JONES 2 FOREWORD FOREWORD FOREWORD INTRODUCTION 3 Senator The Hon Tony GRYBOWSKI Dennis GOLDNER Lindy ALLEN George BRANDIS QC CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER PRESIDENT EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR MINISTER FOR THE ARTS Australia Council for the Arts Regional Arts Australia Regional Arts Australia Belonging: Great Arts Stories from Regional Australia Australian artists are ambitious. They inspire us with Welcome to the fifth publication by Regional Arts The process of writing this book was far more complex will be a source of inspiration to artists and communities their storytelling and challenge us to better understand Australia (RAA) of great art stories from regional, remote than I had imagined. A lot of thought goes into across the country. ourselves, our environment and the rich diversity of our and very remote Australia. These collections have proved interviewing people who have created and driven projects nation. They are creative and innovative in their practice to be very effective for RAA in celebrating the stories of with their communities. We were looking for the idea, These remarkable projects demonstrate the important and daring in their vision. It is the work of our artists regionally-based artists and sharing them with those who the passion, the commitment that drives these artists contribution artists make to regional life, and how that will say the most about our time. support us because they understand our value. These and organisers, often against considerable odds, to realise involvement in arts projects can help to build more accounts clearly demonstrate how important the arts are their vision. -

Tatz MIC Castan Essay Dec 2011

Indigenous Human Rights and History: occasional papers Series Editors: Lynette Russell, Melissa Castan The editors welcome written submissions writing on issues of Indigenous human rights and history. Please send enquiries including an abstract to arts- [email protected]. ISBN 978-0-9872391-0-5 Genocide in Australia: By Accident or Design? Colin Tatz © Indigenous Human Rights and History Vol 1(1). The essays in this series are fully refereed. Editorial committee: John Bradley, Melissa Castan, Stephen Gray, Zane Ma Rhea and Lynette Russell. Genocide in Australia: By Accident or Design? Colin Tatz © Colin Tatz 1 CONTENTS Editor’s Acknowledgements …… 3 Editor’s introduction …… 4 The Context …… 11 Australia and the Genocide Convention …… 12 Perceptions of the Victims …… 18 Killing Members of the Group …… 22 Protection by Segregation …… 29 Forcible Child Removals — the Stolen Generations …… 36 The Politics of Amnesia — Denialism …… 44 The Politics of Apology — Admissions, Regrets and Law Suits …… 53 Eyewitness Accounts — the Killings …… 58 Eyewitness Accounts — the Child Removals …… 68 Moving On, Moving From …… 76 References …… 84 Appendix — Some Known Massacre Sites and Dates …… 100 2 Acknowledgements The Editors would like to thank Dr Stephen Gray, Associate Professor John Bradley and Dr Zane Ma Rhea for their feedback on earlier versions of this essay. Myles Russell-Cook created the design layout and desk-top publishing. Financial assistance was generously provided by the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law and the School of Journalism, Australian and Indigenous Studies. 3 Editor’s introduction This essay is the first in a new series of scholarly discussion papers published jointly by the Monash Indigenous Centre and the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law. -

MS 5014 C.D. Rowley, Study of Aborigines in Australian Society, Social Science Research Council of Australia: Research Material and Indexes, 1964-1968

AIATSIS Collections Catalogue Manuscript Finding Aid Index Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library MS 5014 C.D. Rowley, Study of Aborigines in Australian Society, Social Science Research Council of Australia: research material and indexes, 1964-1968 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY………………………………………….......page 5 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT……………………………..page 5 ACCESS TO COLLECTION………………………………………….…page 6 COLLECTION OVERVIEW……………………………………………..page 7 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE………………………………...………………page 10 SERIES DESCRIPTION………………………………………………...page 12 Series 1 Research material files Folder 1/1 Abstracts Folder 1/2 Agriculture, c.1963-1964 Folder 1/3 Arts, 1936-1965 Folder 1/4 Attitudes, c.1919-1967 Folder 1/5 Bibliographies, c.1960s MS 5014 C.D. Rowley, Study of Aborigines in Australian Society, Social Science Research Council of Australia: research material and indexes, 1964-1968 Folder 1/6 Case Histories, c.1934-1966 Folder 1/7 Cooperatives, c.1954-1965. Folder 1/8 Councils, 1961-1966 Folder 1/9 Courts, Folio A-U, 1-20, 1907-1966 Folder 1/10-11 Civic Rights, Files 1 & 2, 1934-1967 Folder 1/12 Crime, 1964-1967 Folder 1/13 Customs – Native, 1931-1965 Folder 1/14 Demography – Census 1961 – Australia – full-blood Aboriginals Folder 1/15 Demography, 1931-1966 Folder 1/16 Discrimination, 1921-1967 Folder 1/17 Discrimination – Freedom Ride: press cuttings, Feb-Jun 1965 Folder 1/18-19 Economy, Pts.1 & 2, 1934-1967 Folder 1/20-21 Education, Files 1 & 2, 1936-1967 Folder 1/22 Employment, 1924-1967 Folder 1/23 Family, 1965-1966 -

BIOGRAPHIES Yorta Yorta

BIOGRAPHIES Yorta Yorta. Florence’s mother was Pastor Sir Douglas Ralph Nicholls Louisa Frost of the Baraparapa/Wamba. (1906-1988) was born on Louisa was the daughter of Thomas Cummeragunga Aboriginal Station in Frost a stockman on Mathoura station New South Wales on 9 December 1906 and Topsey of the Baraparapa. Doug in Yorta Yorta Country, the land of his was the youngest of six siblings. His Mother and the totemic long neck turtle brothers and sisters included Ernest and emu. His heritage is well recorded (1897-1897), Minnie Nora (1898-1988), and his Ancestors made their own Hilda Melita (1901-1926), Walter Ernest marks in history. Doug Nicholls is a (b.1902-1963) and Howard Herbert multi-clanned descendant of the Yorta (1905-1942). Doug was captain of the Yorta, Baraparapa, Dja Dja Wurrung, Cummeragunga school football team a Jupagalk, and Wergaia Nations through sport he loved and which would carry his mother and father. him through his life. He left school at 14 years of age. In the 1920’s he worked On the patrilineal side of the family, as a tar-boy, channel scooper and Doug Nicholls was the son of Herbert general hand on sheep stations. As well Nicholls (born St. Arnaud 1875-1947) as being quite capable of making a who was the son of Augusta Robinson living, Doug was a gifted athlete. Doug (born Richardson River, near Donald was recruited by the Carlton Football 1859-1886) of the Jupagalk/Wergaia Club but the racism he experienced at and Walpanumin John Logan (born the Club sent him to join the Northcote Charlton 1840-1911) of the Dja Dja Football Club in the VFA. -

Australian Aboriginal Verse 179 Viii Black Words White Page

Australia’s Fourth World Literature i BLACK WORDS WHITE PAGE ABORIGINAL LITERATURE 1929–1988 Australia’s Fourth World Literature iii BLACK WORDS WHITE PAGE ABORIGINAL LITERATURE 1929–1988 Adam Shoemaker THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS iv Black Words White Page E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Previously published by University of Queensland Press Box 42, St Lucia, Queensland 4067, Australia National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Black Words White Page Shoemaker, Adam, 1957- . Black words white page: Aboriginal literature 1929–1988. New ed. Bibliography. Includes index. ISBN 0 9751229 5 9 ISBN 0 9751229 6 7 (Online) 1. Australian literature – Aboriginal authors – History and criticism. 2. Australian literature – 20th century – History and criticism. I. Title. A820.989915 All rights reserved. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organization. All electronic versions prepared by UIN, Melbourne Cover design by Brendon McKinley with an illustration by William Sandy, Emu Dreaming at Kanpi, 1989, acrylic on canvas, 122 x 117 cm. The Australian National University Art Collection First edition © 1989 Adam Shoemaker Second edition © 1992 Adam Shoemaker This edition © 2004 Adam Shoemaker Australia’s Fourth World Literature v To Johanna Dykgraaf, for her time and care -

MS 5133 Papers of Alick and Merle Jackomos 1834 – 2003 CONTENTS

AIATSIS Collections Manuscript Finding Aid index Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library MS 5133 Papers of Alick and Merle Jackomos 1834 – 2003 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY p.3 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT p.3 ACCESS TO COLLECTION p.4 COLLECTION OVERVIEW p.5 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES p.7 Abbreviations p.10 SERIES DESCRIPTION p.11 Series 1 Writings and collations by Merle and Alick Jackomos, together with a transcript of an interview with Alick Jackomos p.11 Series 2 Subject files MS 5133/2/1 Box No.15, ‘Castellorizo Historical’ p.13 MS 5133/2/2 Box No.16, Biographical information on Alick and Merle Jackomos and family p.14 MS 5133/2/3 Box No.17, ‘Letters to me Re Family Trees; Museum; Photos; AIAS/AIATSIS; Stegley Foundation’ p.16 MS 5133/2/4 Box No.18, ‘Aboriginal leaders; Non-Aboriginal leaders; eulogies written by Alick Jackomos’ p.19 MS 5133/2/5 Box No.19(a), ‘Stories by Alick; Aboriginal leaders details; Aboriginal News 1960s; Aboriginal Theatre Cherry Pickers; Bill Onus Corroboree 1949; Helen Bailey Republican/Spain, Aboriginal’ p.26 MS 5133/2/6 Box No.19(b), ‘Lake Tyers, Ramahyuck, Gippsland’ .p.29 MS 5133/2/7 Box No.20, ‘References, Awards, Alick, Merle, Stan Davey, J. Moriarty’ p.35 MS 5133/2/8 Box No.21, ‘Religion, odds, etc.’ .p.39 MS 5133, Papers of Alick and Merle Jackomos, 1834 - 2003 MS 5133/2/9 Box No.22, ‘Maloga – Cummeragunja, Doug Nicholls, Thomas James, William Cooper, Marge Tucker, Hostels Ltd’ .p.40 MS 5133/2/10 Box No.23, ‘Lake Boga, Framlingham, Coranderrk, Antwerp, other missions, -

The Aboriginal Struggle & the Left

The Aboriginal Struggle & the Left Terry Townshend 2 The Aboriginal Struggle & the Left About the author Terry Townsend was a longtime member of the Democratic Socialist Party and now the Socialist Alliance. He edited the online journal Links (links.org) and has been a frequent contributor to Green Left Weekly (greenleft.org.au). Note on quotations For ease of reading, we have made minor stylistic changes to quotations to make their capitalisation consistent with the rest of the book. The exception, however, concerns Aborigines, Aboriginal, etc., the capitalisation of which has been left unchanged as it may have political significance. Resistance Books 2009 ISBN 978-1-876646-60-8 Published by Resistance Books, resistanceboks.com Contents Preface...........................................................................................................................5 Beginnings.....................................................................................................................7 The North Australian Workers Union in the 1920s and ’30s.....................................9 Comintern Influence..................................................................................................12 The 1930s....................................................................................................................15 Aboriginal-Led Organisations & the Day of Mourning............................................19 Struggles in the 1940s: The Pilbara Stock Workers’ Strike........................................23 The 1940s: Communists -

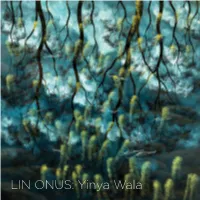

LIN ONUS: Yinya Wala Image Courtesy of Andrew Chapman Photography

LIN ONUS: Yinya Wala Image courtesy of Andrew Chapman Photography LIN ONUS: Yinya Wala Lin Onus writes his own history. In doing so he not only raises questions about the place Aboriginal art occupies in Australian art history and his location within each, but its inextricable relationship to colonial history. He ‘reads’ the events and processes of history and inscribes them into the present with an eye to the future for the purposes of conciliation. In the dynamic cycles of definition and re-definition, possession and dispossession that have marked the history of Aboriginal affairs in Australia. Onus has challenged western art definitions of history. Onus was a cultural terrorist of gentle irreverence who not only straddled a cusp in cultural history between millennia but brought differences together not through fusion but through bridging the Left: (Detail) divides making him exemplary in the way he explores what it means to Riddle of the Koi (diptych), 1994 be Australian. Margo Neale, ‘Tribute – Lin Onus’, Artlink, Issue 20:1, March 2000 Cover: Fish at Malwan, 1996 synthetic polymer paint on canvas 182 x 182 cm 3 Foreword Lin Onus (1948-1996) was one of the most successful and influential Australian Indigenous artists of his generation whose work was empowered by a sensitive and sophisticated blending of traditional Aboriginal designs and Western art; specifically, this meant including rarrk (cross hatching) within his own particular style of photo-realism. This enabled him to connect with a unique and powerful voice that impacted on a wide cross-cultural and political arena, both within Australia and internationally. -

The Melba – Special Edition 2019

2008 Year by year we celebrate Melba Opera Trust Contents Page 2-3 2008-09 WELCOMING THE NEW MELBA Page 4-5 2010 Page 6-7 2011 In 2008 a new philanthropic body founded on the distinguished determined to carrying forward expressed a clear objective: to grow Page 8-9 2012 history and traditions of Melba Conservatorium of Music was formed: the three commitments implicit a capital endowment that would the Dame Nellie Melba Opera Trust. in Dame Nellie Melba’s legacy – provide valuable scholarships Page 10-11 2013 namely to students, singing and to support the development of Dame Nellie taught at the to embody precisely the same scholarships. young Australian operatic talent Page 12 2014 Conservatorium of Music, purposes and values that sustained into perpetuity “so that another Melbourne (later renamed in her the Melba Conservatorium for 108 The existing company identity, Page 13 2015 Melba may arise”. This vision was honour) and was especially fond of years: to ensure that promising structure and independence led by then-General Manager, Page 14 2016 the institution for its nurturing and young Australian singers are of Melba Conservatorium were Amy McPartlan (now CEO Amy supportive approach. supported financially during a preserved within the new entity and Page 15-16 2017 Black) with the transition from crucial phase of their development its reimagined purpose. Following a widespread feasibility Conservatorium to Trust wisely Page 17 2018 – in this case, postgraduate training study and community ‘think-tank’, The Board, led at the time by guided by then Director, Professor as the bridge to a professional Page 18-19 2019 Melba Opera Trust was established Chair Robert G. -

How to Reposition the Social, Cultural and Economic Value

GALNYA ON WOKA PROSPERITY ON COUNTRY: HOW TO REPOSITION THE SOCIAL, CULTURAL AND ECONOMIC VALUE OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLE IN THE GOULBURN MURRAY REGION Raelene L. Nixon ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7532-0995 Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Melbourne Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Science December 2020 1 DECLARATION This is to certify that: I. The thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD II. Due acknowledgment has been made in the text to all other material used III. The thesis is approximately 79 081 words Raelene Nixon December 2020 2 ABSTRACT Prime Minister Gillard's 'Closing the Gap' speech in February 2011 called on the country's First Peoples to take responsibility for improving their situation. This kind of rhetoric highlights one of the underlying reasons there has been no substantial improvement in the position of Indigenous Australian peoples. Indigenous peoples are predominately identified as 'the problem' and positioned as the agents who need to 'fix it', which ignores the influence of dominant culture in maintaining the current position of Indigenous peoples. Drawing on the experience and knowledge of Indigenous and government leaders working on strategies to empower Indigenous communities, this thesis captures the work undertaken in the Goulburn Murray region of Victoria in the quest to reposition the social, cultural and economic value of Indigenous peoples. For substantive change to be made, power relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians need to be realigned and dominant social structures reconstituted. Only once these shifts have been made can the country’s original inhabitants enjoy parity in education, health, employment, and economic prosperity. -

Special List Index for GRG52/90

Special List GRG52/90 Newspaper cuttings relating to aboriginal matters This series contains seven volumes of newspaper clippings, predominantly from metropolitan and regional South Australian newspapers although some interstate and national newspapers are also included, especially in later years. Articles relate to individuals as well as a wide range of issues affecting Aboriginals including citizenship, achievement, sport, art, culture, education, assimilation, living conditions, pay equality, discrimination, crime, and Aboriginal rights. Language used within articles reflects attitudes of the time. Please note that the newspaper clippings contain names and images of deceased persons which some readers may find distressing. Series date range 1918 to 1970 Index date range 1918 to 1970 Series contents Newspaper cuttings, arranged chronologically Index contents Arranged chronologically Special List | GRG52/90 | 12 April 2021 | Page 1 How to view the records Use the index to locate an article that you are interested in reading. At this stage you may like to check whether a digitised copy of the article is available to view through Trove. Articles post-1954 are unlikely to be found online via Trove. If you would like to view the record(s) in our Research Centre, please visit our Research Centre web page to book an appointment and order the records. You may also request a digital copy (fees may apply) through our Online Enquiry Form. Agency responsible: Aboriginal Affairs and Reconciliation Access Determination: Open Note: While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of special lists, some errors may have occurred during the transcription and conversion processes. It is best to both search and browse the lists as surnames and first names may also have been recorded in the registers using a range of spellings. -

Māori and Aboriginal Women in the Public Eye

MĀORI AND ABORIGINAL WOMEN IN THE PUBLIC EYE REPRESENTING DIFFERENCE, 1950–2000 MĀORI AND ABORIGINAL WOMEN IN THE PUBLIC EYE REPRESENTING DIFFERENCE, 1950–2000 KAREN FOX THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Fox, Karen. Title: Māori and Aboriginal women in the public eye : representing difference, 1950-2000 / Karen Fox. ISBN: 9781921862618 (pbk.) 9781921862625 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Women, Māori--New Zealand--History. Women, Aboriginal Australian--Australia--History. Women, Māori--New Zealand--Social conditions. Women, Aboriginal Australian--Australia--Social conditions. Indigenous women--New Zealand--Public opinion. Indigenous women--Australia--Public opinion. Women in popular culture--New Zealand. Women in popular culture--Australia. Indigenous peoples in popular culture--New Zealand. Indigenous peoples in popular culture--Australia. Dewey Number: 305.4880099442 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover image: ‘Maori guide Rangi at Whakarewarewa, New Zealand, 1935’, PIC/8725/635 LOC Album 1056/D. National Library of Australia, Canberra. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Abbreviations . ix Illustrations . xi Glossary of Māori Words . xiii Note on Usage . xv Introduction . 1 Chapter One .