Australian Indigenous Petitions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011 Administering Justice for the Community for 150 Years

The Supreme Court of Western Australia 1861 - 2011 Administering Justice for the Community for 150 years by The Honourable Wayne Martin Chief Justice of Western Australia Ceremonial Sitting - Court No 1 17 June 2011 Ceremonial Sitting - Administering Justice for the Community for 150 Years The court sits today to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the creation of the court. We do so one day prematurely, as the ordinance creating the court was promulgated on 18 June 1861, but today is the closest sitting day to the anniversary, which will be marked by a dinner to be held at Government House tomorrow evening. Welcome I would particularly like to welcome our many distinguished guests, the Rt Hon Dame Sian Elias GNZM, Chief Justice of New Zealand, the Hon Terry Higgins AO, Chief Justice of the ACT, the Hon Justice Geoffrey Nettle representing the Supreme Court of Victoria, the Hon Justice Roslyn Atkinson representing the Supreme Court of Queensland, Mr Malcolm McCusker AO, the Governor Designate, the Hon Justice Stephen Thackray, Chief Judge of the Family Court of WA, His Honour Judge Peter Martino, Chief Judge of the District Court, President Denis Reynolds of the Children's Court, the Hon Justice Neil McKerracher of the Federal Court of Australia and many other distinguished guests too numerous to mention. The Chief Justice of Australia, the Hon Robert French AC had planned to join us, but those plans have been thwarted by a cloud of volcanic ash. We are, however, very pleased that Her Honour Val French is able to join us. I should also mention that the Chief Justice of New South Wales, the Hon Tom Bathurst, is unable to be present this afternoon, but will be attending the commemorative dinner to be held tomorrow evening. -

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY and CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, 9 Fellows Road (Coombs Building), The Australian National University, Acton, ACT, 2601, or [email protected]. WARNING: Readers are notified that this publication may contain names or images of deceased persons. ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE UNCLE ROY PATTERSON AND JENNIFER JONES Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760464066 ISBN (online): 9781760464073 WorldCat (print): 1224453432 WorldCat (online): 1224452874 DOI: 10.22459/OTL.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph: Patterson family photograph, circa 1904 This edition © 2020 ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. Contents Acknowledgements ....................................... vii Note on terminology ......................................ix Preface .................................................xi Introduction: Meeting and working with Uncle Roy ..............1 Part 1: Sharing Taungurung history 1. -

Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth-Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals

Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth-Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals Eva Bischoff Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series Series Editors Richard Drayton Department of History King’s College London London, UK Saul Dubow Magdalene College University of Cambridge Cambridge, UK The Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies series is a collection of studies on empires in world history and on the societies and cultures which emerged from colonialism. It includes both transnational, comparative and connective studies, and studies which address where particular regions or nations participate in global phenomena. While in the past the series focused on the British Empire and Commonwealth, in its current incarna- tion there is no imperial system, period of human history or part of the world which lies outside of its compass. While we particularly welcome the first monographs of young researchers, we also seek major studies by more senior scholars, and welcome collections of essays with a strong thematic focus. The series includes work on politics, economics, culture, literature, science, art, medicine, and war. Our aim is to collect the most exciting new scholarship on world history with an imperial theme. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/13937 Eva Bischoff Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth- Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals Eva Bischoff Department of International History Trier University Trier, Germany Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series ISBN 978-3-030-32666-1 ISBN 978-3-030-32667-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32667-8 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 This work is subject to copyright. -

RAA-Belonging Final Lores

BELONG aGREATARTSSTORIES ING FROM REGIONAL AUSTRALIAb written from conversations with aLindy ALLEN SNAPSHOTS based on interviews with aHélène SOBOLEWSKI edited by aMoya SAYER-JONES 2 FOREWORD FOREWORD FOREWORD INTRODUCTION 3 Senator The Hon Tony GRYBOWSKI Dennis GOLDNER Lindy ALLEN George BRANDIS QC CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER PRESIDENT EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR MINISTER FOR THE ARTS Australia Council for the Arts Regional Arts Australia Regional Arts Australia Belonging: Great Arts Stories from Regional Australia Australian artists are ambitious. They inspire us with Welcome to the fifth publication by Regional Arts The process of writing this book was far more complex will be a source of inspiration to artists and communities their storytelling and challenge us to better understand Australia (RAA) of great art stories from regional, remote than I had imagined. A lot of thought goes into across the country. ourselves, our environment and the rich diversity of our and very remote Australia. These collections have proved interviewing people who have created and driven projects nation. They are creative and innovative in their practice to be very effective for RAA in celebrating the stories of with their communities. We were looking for the idea, These remarkable projects demonstrate the important and daring in their vision. It is the work of our artists regionally-based artists and sharing them with those who the passion, the commitment that drives these artists contribution artists make to regional life, and how that will say the most about our time. support us because they understand our value. These and organisers, often against considerable odds, to realise involvement in arts projects can help to build more accounts clearly demonstrate how important the arts are their vision. -

Hope for the Future for I Know the Plans I Have for You,” Declares the Lord, “Plans to Prosper You and Not to Harm You, Plans to Give You Hope and a Future

ISSUE 3 {2017} BRINGING THE LIGHT OF CHRIST INTO COMMUNITIES Hope for the future For I know the plans I have for you,” declares the Lord, “plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future Jeremiah 29:11 Lifting their voices What it’s like in their world Our first Children and Youth A new product enables participants Advocate will be responsible to experience the physical and for giving children and young mental challenges faced by people people a greater voice. living with dementia. networking ׀ 1 When Jesus spoke again to the people, he said, I am the light of the world. Contents Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness, but will have the light of life. John 8:12 (NIV) 18 9 20 30 8 15 24 39 From the Editor 4 Zillmere celebrates 135 years 16 Research paves way for better care 30 networking Churches of Christ in Queensland Chief Executive Officer update 5 Kenmore Campus - ready for the future 17 Annual Centrifuge conference round up 31 41 Brookfield Road Kenmore Qld 4069 PO Box 508 Kenmore Qld 4069 Spiritual Mentoring: Companioning Souls 7 Hope for future managers 19 After the beginnings 32 07 3327 1600 [email protected] Church of the Outback 8 Celebrating the first Australians 20 Gidgee’s enterprising ways 33 networking contains a variety of news and stories from Donations continue life of mission 9 Young, vulnerable and marginalised 22 People and Events 34 across Churches of Christ in Queensland. Articles and photos can be submitted to [email protected]. -

Intimacies of Violence in the Settler Colony Economies of Dispossession Around the Pacific Rim

Cambridge Imperial & Post-Colonial Studies INTIMACIES OF VIOLENCE IN THE SETTLER COLONY ECONOMIES OF DISPOSSESSION AROUND THE PACIFIC RIM EDITED BY PENELOPE EDMONDS & AMANDA NETTELBECK Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series Series Editors Richard Drayton Department of History King’s College London London, UK Saul Dubow Magdalene College University of Cambridge Cambridge, UK The Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies series is a collection of studies on empires in world history and on the societies and cultures which emerged from colonialism. It includes both transnational, comparative and connective studies, and studies which address where particular regions or nations participate in global phenomena. While in the past the series focused on the British Empire and Commonwealth, in its current incarna- tion there is no imperial system, period of human history or part of the world which lies outside of its compass. While we particularly welcome the first monographs of young researchers, we also seek major studies by more senior scholars, and welcome collections of essays with a strong thematic focus. The series includes work on politics, economics, culture, literature, science, art, medicine, and war. Our aim is to collect the most exciting new scholarship on world history with an imperial theme. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/13937 Penelope Edmonds Amanda Nettelbeck Editors Intimacies of Violence in the Settler Colony Economies of Dispossession around the Pacific Rim Editors Penelope Edmonds Amanda Nettelbeck School of Humanities School of Humanities University of Tasmania University of Adelaide Hobart, TAS, Australia Adelaide, SA, Australia Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series ISBN 978-3-319-76230-2 ISBN 978-3-319-76231-9 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76231-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018941557 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018 This work is subject to copyright. -

The History of NAIDOC Celebrating Indigenous Culture

The History of NAIDOC Celebrating Indigenous Culture latrobe.edu.au CRICOS Provider 00115M Wominjeka Welcome La Trobe University 22 Acknowledgement La Trobe University acknowledges the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nations as the traditional custodians of the land upon which the Bundoora campus is located. LaLa Trobe Trobe University University 33 Acknowledgement We recognise their ongoing connection to the land and value the unique contribution the Wurundjeri people and all Indigenous Australians make to the University and the wider Australian society. LaLa Trobe Trobe University University 44 What is NAIDOC? NAIDOC stands for the ‘National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee’. This committee was responsible for organising national activities during NAIDOC Week and its acronym has since become the name of the week itself. La Trobe University 55 History of NAIDOC NAIDOC Week celebrations are held across Australia each July to celebrate the history, culture and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. NAIDOC is celebrated not only in Indigenous communities, but by Australians from all walks of life. La Trobe University 66 History of NAIDOC 1920-1930 Before the 1920s, Aboriginal rights groups boycotted Australia Day (26 January) in protest against the status and treatment of Indigenous Australians. Several organisations emerged to fill this role, particularly the Australian Aborigines Progressive Association (AAPA) in 1924 and the Australian Aborigines League (AAL) in 1932. La Trobe University 77 History of NAIDOC 1930’s In 1935, William Cooper, founder of the AAL, drafted a petition to send to King George V, asking for special Aboriginal electorates in Federal Parliament. The Australian Government believed that the petition fell outside its constitutional Responsibilities William Cooper (c. -

DISCOVER ABORIGINAL EXPERIENCES – NEWS February 2020

DISCOVER ABORIGINAL EXPERIENCES – NEWS February 2020 WelcoMiNG 5 NEW MEMbers We are pleased to welcome and introduce five new businesses in 2020, taking the collective to 45 members that offer over 140 Aboriginal guided experiences spanning the breadth of the Australian continent in both urban and regional locations. Discover Aboriginal Experiences is Culture Connect, Queensland Jarramali Rock Art Tours, Queensland a flagship suite of extraordinary The rich cultural traditions and extraordinary The Quinkan rock art, found around the tiny Aboriginal experiences, showcasing natural landscapes of Tropical North Queensland northern Queensland town of Laura, is remarkable the world’s oldest living culture are the backbone of Culture Connect’s experiences in itself: named one of the 10 most significant through cultural insights, authentic that offer intimate, genuine connections with rock art sites in the world by UNESCO. But getting Indigenous owners through day, multi day or to this remote locale with Jarramali Rock Art Tours experiences, meaningful connections, private charters. This could mean hunting for is an unforgettable adventure, too. Travel to the fun and adventure. mud crabs on Cooya Beach with brothers Linc and Magnificent Gallery either by 4WD, crossing the Brandon Walker, watching artist Brian “Binna” wild terrain of the Maytown to Laura Coach Road, Swindley creating work that overflows with or take a helitour from Cairns, swooping over reef, For further information: Dreamtime stories or having exclusive access to rainforest and -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

Day of Mourning – Overview Fact Sheet

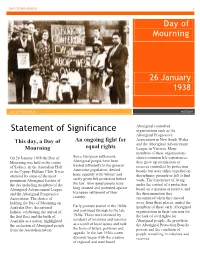

DAY OF MOURNING 1 Day of Mourning 26 January 1938 DAY OF MOURNING HISTORY Aboriginal controlled Statement of Significance organisations such as the Aboriginal Progressive Association in New South Wales An ongoing fight for This day, a Day of and the Aboriginal Advancement Mourning equal rights League in Victoria. Many members of these organisations On 26 January 1938 the Day of Since European settlement, shared common life experiences; Mourning was held in the centre Aboriginal people have been they grew up on missions or of Sydney, in the Australian Hall treated differently to the general reserves controlled by protection at the Cyprus Hellene Club. It was Australian population; denied boards but were either expelled on attended by some of the most basic equality with 'whites' and disciplinary grounds or left to find prominent Aboriginal leaders of rarely given full protection before work. The experience of living the day including members of the the law. Aboriginal people have under the control of a protection Aboriginal Advancement League long resisted and protested against board on a mission or reserve, and and the Aboriginal Progressive European settlement of their the discrimination they Association. The choice of country. encountered when they moved holding the Day of Mourning on away from these places, united the Australia Day, the national Early protests started in the 1840s members of these early Aboriginal holiday celebrating the arrival of and continued through to the late organisations in their concerns for the first fleet and the birth of 1920s. These were initiated by the lack of civil rights for Australia as a nation, highlighted residents of missions and reserves Aboriginal people, the growth in the exclusion of Aboriginal people as a result of local issues and took the Aboriginal Protection Board's from the Australian nation. -

Gladys Nicholls: an Urban Aboriginal Leader in Post-War Victoria

Gladys Nicholls: An Urban Aboriginal Leader in Post-war Victoria Patricia Grimshaw School of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC. 3010 [email protected] Abstract: Gladys Nicholls was an Aboriginal activist in mid-20 th century Victoria who made significant contributions to the development of support networks for the expanding urban Aboriginal community of inner-city Melbourne. She was a key member of a talented group of Indigenous Australians, including her husband Pastor Doug Nicholls, who worked at a local, state and national level to improve the economic wellbeing and civil rights of their people, including for the 1967 Referendum. Those who knew her remember her determined personality, her political intelligence and her unrelenting commitment to building a better future for Aboriginal people. Keywords: Aboriginal women, Aboriginal activism, Gladys Nicholls, Pastor Doug Nicholls, assimilation, Victorian Aborigines Advancement League, 1967 Referendum Gladys Nicholls (1906–1981) was an Indigenous leader who was significant from the 1940s to the 1970s, first, in action to improve conditions for Aboriginal people in Melbourne and second, in grassroots activism for Indigenous rights across Australia. When the Victorian government inscribed her name on the Victorian Women’s Honour Roll in 2008, the citation prepared by historian Richard Broome read as follows: ‘Lady Gladys Nicholls was an inspiration to Indigenous People, being a role model for young women, a leader in advocacy for the rights of Indigenous people as well as a tireless contributor to the community’. 1 Her leadership was marked by strong collaboration and co-operation with like-minded women and men, both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, who were at the forefront of Indigenous reform, including her prominent husband, Pastor (later Sir) Doug Nicholls. -

Racist Structures and Ideologies Regarding Aboriginal People in Contemporary and Historical Australian Society

Master Thesis In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science: Development and Rural Innovation Racist structures and ideologies regarding Aboriginal people in contemporary and historical Australian society Robin Anne Gravemaker Student number: 951226276130 June 2020 Supervisor: Elisabet Rasch Chair group: Sociology of Development and Change Course code: SDC-80436 Wageningen University & Research i Abstract Severe inequalities remain in Australian society between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people. This research has examined the role of race and racism in historical Victoria and in the contemporary Australian government, using a structuralist, constructivist framework. It was found that historical approaches to governing Aboriginal people were paternalistic and assimilationist. Institutions like the Central Board for the Protection of Aborigines, which terrorised Aboriginal people for over a century, were creating a racist structure fuelled by racist ideologies. Despite continuous activism by Aboriginal people, it took until 1967 for them to get citizens’ rights. That year, Aboriginal affairs were shifted from state jurisdiction to national jurisdiction. Aboriginal people continue to be underrepresented in positions of power and still lack self-determination. The national government of Australia has reproduced historical inequalities since 1967, and racist structures and ideologies remain. ii iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Elisabet Rasch, for her support and constructive criticism. I thank my informants and other friends that I met in Melbourne for talking to me and expanding my mind. Floor, thank you for showing me around in Melbourne and for your never-ending encouragement since then, via phone, postcard or in person. Duane Hamacher helped me tremendously by encouraging me to change the topic of my research and by sharing his own experiences as a researcher.