Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![96 C.L.R.] of Australia. 563 Elder's Trustee And](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6383/96-c-l-r-of-australia-563-elders-trustee-and-66383.webp)

96 C.L.R.] of Australia. 563 Elder's Trustee And

96 C.L.R.] OF AUSTRALIA. 563 [HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA.] ELDER'S TRUSTEE AND EXECUTORY APPELLANT ; COMPANY LIMITED . ./ AND FEDERAL COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION RESPONDENT. Estate Duty {Cth.)—Company shares—Valuation—Principles to be applied—Com- H. C. OF A. pany engaged in pastoral pursuits in semi-arid areas—-Weight to be attached to 1951. results in past years—-Allowance for reserves—Estate Duty Assessment Act 1914-1942. Adelaide, Sept. 21, 24, The estate of a deceased person included a small proportion of the issued 25; shares of a company which owned and operated four grazing properties. One Sydney, property had been and one was about to be converted from sheep to cattle, Nov. 5. and the other two were sheep stations. All were in semi-arid areas and sub- ject to special hazards. The company's shares were not quoted on a stock Kitto J. exchange. Held that in applying ordinary principles of valuation to the valuation of shares, it should be recognised that ordinarily a purchaser is likely to be influenced, as to price, mainly by his opinion concerning the dividends which the shares may reasonably be expected to produce. In the present case, having regard to the nature and characteristics of the company's business, a hypothetical purchaser buying at the date of death of the deceased would have looked for a high assets-backmg for the shares, as well as for a high average dividend arrived at after making substantial allowances for reserves. The selection of suitable test periods, and the adjustments to be made in using the company's accounts of the selected periods in order to estimate the profits which might have been regarded at the date of death as likely to be made by the company in the future, considered. -

Total Solar Eclipse of 2002 December 4

NASA/TP—2001–209990 Total Solar Eclipse of 2002 December 04 F. Espenak and J. Anderson Central Lat,Lng = -28.0 132.0 P Factor = 0.46 Semi W,H = 0.35 0.28 Offset X,Y = 0.00-0.00 1999 Oct 26 10:40:42 AM High Res World Data [WPD1] WorldMap v2.00, F. Espenak Orthographic Projection Scale = 8.00 mm/° = 1:13915000 Central Lat,Lng = -10.0 26.0 P Factor = 0.31 Semi W,H = 0.70 0.50 Offset X,Y = 0.00-0.00 1999 Oct 26 10:17:57 AM September 2001 The NASA STI Program Office … in Profile Since its founding, NASA has been dedicated to • CONFERENCE PUBLICATION. Collected the advancement of aeronautics and space papers from scientific and technical science. The NASA Scientific and Technical conferences, symposia, seminars, or other Information (STI) Program Office plays a key meetings sponsored or cosponsored by NASA. part in helping NASA maintain this important role. • SPECIAL PUBLICATION. Scientific, techni- cal, or historical information from NASA The NASA STI Program Office is operated by programs, projects, and mission, often con- Langley Research Center, the lead center for cerned with subjects having substantial public NASA’s scientific and technical information. The interest. NASA STI Program Office provides access to the NASA STI Database, the largest collection of • TECHNICAL TRANSLATION. aeronautical and space science STI in the world. English-language translations of foreign scien- The Program Office is also NASA’s institutional tific and technical material pertinent to NASA’s mechanism for disseminating the results of its mission. -

Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla Grammar This Book Is Available As a Free Fully-Searchable Ebook from Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla Grammar

Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla grammar This book is available as a free fully-searchable ebook from www.adelaide.edu.au/press Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla grammar A commentary on the first section of A vocabulary of the Parnkalla language (revised edition 2018) by Mark Clendon Linguistics Department, Faculty of Arts The University of Adelaide Clamor Wilhelm Schürmann Published in Adelaide by University of Adelaide Press The University of Adelaide Level 14, 115 Grenfell Street South Australia 5005 [email protected] www.adelaide.edu.au/press The University of Adelaide Press publishes externally refereed scholarly books by staff of the University of Adelaide. It aims to maximise access to the University’s best research by publishing works through the internet as free downloads and for sale as high quality printed volumes. © 2015 Mark Clendon, 2018 for this revised edition This work is licenced under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. This licence allows for the copying, distribution, display and performance of this work for non-commercial purposes providing the work is clearly attributed to the copyright holders. Address all inquiries to the Director at the above address. For the full Cataloguing-in-Publication data please contact the National Library of Australia: [email protected] -

Coober Pedy, South Australia

The etymology of Coober Pedy, South Australia Petter Naessan The aim of this paper is to outline and assess the diverging etymologies of ‘Coober Pedy’ in northern South Australia, in the search for original and post-contact local Indigenous significance associated with the name and the region. At the interface of contemporary Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara opinion (mainly in the Coober Pedy region, where I have conducted fieldwork since 1999) and other sources, an interesting picture emerges: in the current use by Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara people as well as non-Indigenous people in Coober Pedy, the name ‘Coober Pedy’ – as ‘white man’s hole (in the ground)’ – does not seem to reflect or point toward a pre-contact Indigenous presence. Coober Pedy is an opal mining and tourist town with a total population of about 3500, situated near the Stuart Highway, about 850 kilometres north of Adelaide, South Australia. Coober Pedy is close to the Stuart Range, lies within the Arckaringa Basin and is near the border of the Great Victoria Desert. Low spinifex grasslands amounts for most of the sparse vegetation. The Coober Pedy and Oodnadatta region is characterised by dwarf shrubland and tussock grassland. Further north and northwest, low open shrub savanna and open shrub woodland dominates.1 Coober Pedy and surrounding regions are arid and exhibit very unpredictable rainfall. Much of the economic activity in the region (as well as the initial settlement of Euro-Australian invaders) is directly related to the geology, namely quite large deposits of opal. The area was only settled by non-Indigenous people after 1915 when opal was uncovered but traditionally the Indigenous population was western Arabana (Midlaliri). -

Vol No Artist Title Date Medium Comments 1 Acraman, William

Tregenza PRG 1336 SOUTH AUSTRALIAN HISTORICAL PICTURES INDEX ARTIST INDEX (Series 1) (Information taken from photo - some spellings may be incorrect) Vol No Artist Title Date Medium Comments 1 Acraman, William Residence of E Castle Esq re Hackham Morphett Vale 1856 Pencil 1 Adamson, James Hazel Early South Australian view 1 Adamson, James Hazel Lady Augusta & Eureka Capt Cadell's first vessels on Murray 1853 Lithograph 1 Adamson, James Hazel The Goolwa 1853 Lithograph 1 Adamson, James Hazel Agricultural show at Frome Road 1853 W/c 1 Adamson, James Hazel Jetty at Port Noarlunga with Yatala in background 1855 W/c 1 Adamson, James Hazel Panorama of Goolwa from water showing Steamer Lady Augusta 1854 Pencil & wash No photo 1 Angas, George French SA Illustrated photocopies of plates List in front 1 Angas, George French Portraits (2) 1 Angas, George French Devil's Punch Bowl 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Encounter Bay looking south 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Interior of crater, Mount Shanck 1844 W/c Plus current 1 Angas, George French Lake Albert 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Mt Lofty from Rapid Bay W/c 1 Angas, George French Interior of Principal Crater Mt Gambier - evening 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Penguin Island near Rivoli Bay 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Port Adelaide 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Port Lincoln from Winter's Hill 1845 W/c 1 Angas, George French Scene of the Coorong at the Narrows 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French The Goolwa - evening W/c 1 Angas, George French Sea mouth of the Murray 1844-45 W/c 1 Angas, -

Management Plan for Recreational Fishing in South Australia

Management Plan for Recreational Fishing in South Australia August 2020 Information current as of 14 August 2020 © Government of South Australia 2020 Disclaimer PIRSA and its employees do not warrant or make any representation regarding the use, or results of the use, of the information contained herein as regards to its correctness, accuracy, reliability and currency or otherwise. PIRSA and its employees expressly disclaim all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or advice. All enquiries Primary Industries and Regions SA (PIRSA) Level 15, 25 Grenfell Street GPO Box 1671, Adelaide SA 5001 T: 08 8226 0900 E: [email protected] - 2 - Table of Contents 1 Fishery to which this plan applies ................................................................................. 5 2 Consistency with other management plans .................................................................. 5 3 Term of the plan and review of the plan ........................................................................ 6 4 Fisheries management in South Australia .................................................................... 6 5 Description of the fishery .............................................................................................. 7 5.1 Biological and environmental characteristics .......................................................... 9 5.2 Biology of key recreational species ....................................................................... 11 5.3 Social and economic characteristics .................................................................... -

Key Railway Crossings Overlay 113411.4 94795 ! Port Augusta ! !

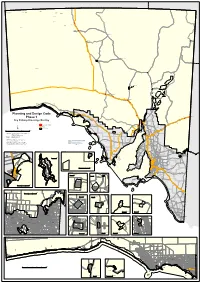

N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y Amata ! Kalka Kanpi ! ! Nyapari Pipalyatjara ! ! Pukatja ! Yunyarinyi ! Umuwa ! QUEENSLAND Kaltjiti ! !113411.4 94795 Indulkana ! Mimili ! Watarru ! 113411.4 94795 Mintabie ! ! ! Marla Oodnadatta ! Innamincka Cadney Park ! ! Moomba ! WESTERN AUSTRALIA William Creek ! Coober Pedy ! Oak Valley ! Marree ! ! Lyndhurst Arkaroola ! Andamooka ! Roxby Downs ! Copley ! ! Nepabunna Leigh Creek ! Tarcoola ! Beltana ! 113411.4 94795 !! 113411.4 94795 Kingoonya ! Glendambo !113411.4 94795 Parachilna ! ! Blinman ! Woomera !!113411.4 94795 Pimba !113411.4 94795 Nullarbor Roadhouse Yalata ! ! ! Wilpena Border ! Village ! Nundroo Bookabie ! Coorabie ! Penong ! NEW SOUTH WALES ! Fowlers Bay FLINDERS RANGES !113411.4 94795 Planning and Design Code ! 113411.4 94795 ! Ceduna CEDUNA Cockburn Mingary !113411.4 94795 ! ! Phase 1 !113411.4 94795 Olary ! Key Railway Crossings Overlay 113411.4 94795 ! Port Augusta ! ! !113411.4 94795 Manna Hill ! STREAKY BAY Key Railway Crossings Yunta ! Iron Knob Railway MOUNT REMARKABLE ± Phase 1 extent PETERBOROUGH 0 50 100 150 km Iron Baron ! !!115768.8 17888 WUDINNA WHYALLA KIMBA Whyalla Produced by Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure Development Division ! GPO Box 1815 Adelaide SA 5001 Port Pirie www.sa.gov.au NORTHERN Projection Lambert Conformal Conic AREAS Compiled 11 January 2019 © Government of South Australia 2019 FRANKLIN No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted PORT in any form, or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, HARBOUR Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure. PIRIE ELLISTON CLEVE While every reasonable effort has been made to ensure that this document is correct at GOYDER the time of publication, the State of South Australia and its agencies, instrumentalities, employees and contractors disclaim any and all liability to any person in respect to anything or the consequence of anything done or omitted to be done in reliance upon the whole or any part of this document. -

Racist Structures and Ideologies Regarding Aboriginal People in Contemporary and Historical Australian Society

Master Thesis In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science: Development and Rural Innovation Racist structures and ideologies regarding Aboriginal people in contemporary and historical Australian society Robin Anne Gravemaker Student number: 951226276130 June 2020 Supervisor: Elisabet Rasch Chair group: Sociology of Development and Change Course code: SDC-80436 Wageningen University & Research i Abstract Severe inequalities remain in Australian society between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people. This research has examined the role of race and racism in historical Victoria and in the contemporary Australian government, using a structuralist, constructivist framework. It was found that historical approaches to governing Aboriginal people were paternalistic and assimilationist. Institutions like the Central Board for the Protection of Aborigines, which terrorised Aboriginal people for over a century, were creating a racist structure fuelled by racist ideologies. Despite continuous activism by Aboriginal people, it took until 1967 for them to get citizens’ rights. That year, Aboriginal affairs were shifted from state jurisdiction to national jurisdiction. Aboriginal people continue to be underrepresented in positions of power and still lack self-determination. The national government of Australia has reproduced historical inequalities since 1967, and racist structures and ideologies remain. ii iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Elisabet Rasch, for her support and constructive criticism. I thank my informants and other friends that I met in Melbourne for talking to me and expanding my mind. Floor, thank you for showing me around in Melbourne and for your never-ending encouragement since then, via phone, postcard or in person. Duane Hamacher helped me tremendously by encouraging me to change the topic of my research and by sharing his own experiences as a researcher. -

Stretch Reconciliation Action Plan

Reconciliation Action Plan 2018 – 2020 Underwater Garden by Timeisha Simpson Timeisha Simpson is an emerging artist from Port Lincoln who has exhibited both on the West Coast and in Adelaide. She was studying in Year 9 when she created this work as part of Port Lincoln High School’s (PLHS) Aboriginal Arts Program. The PLHS Arts Program is an outlet for young artists to express themselves creatively. Local artist Jenny Silver has been working with the Arts Program for some time and has built strong relationships with all of the participating young artists. Many of the art works produced explore connections with culture, identity, family and place. It provides opportunities for the artists to be part of exhibitions across the state and their success at these exhibitions has created positive discussions with the wider community. An important aspect of the program is the emphasis on enterprise and the creation of individual artist portfolios. Jenny worked with Timeisha to create Underwater Garden, an acrylic painting that celebrates the richness and health of the water around Port Lincoln. Both artists spend a lot of time in the ocean and chose seaweed to represent growth and movement. Timeisha and Jenny developed authentic relationships with the community while on country which was integral in initial ideation for this piece. Timeisha says, ”The painting celebrates all the different bright coloured seaweeds in the ocean, I see these seaweeds when I go diving, snorkelling and fishing at the Port Lincoln National Park with my friends and family. I really enjoy going to Engine Point because that is where we go diving and snorkelling off the rocks, and for fishing we go to Salmon Hole and other cliff areas”. -

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (The Department) to the Questions on Notice That Arose Duringthe 6 February Public Hearing of the Committee

~ubmission N~. C~ ~ Australian Government I-v. Department ofAgriculture, Fisheries and Fores~ Date Received.. ~ o ~ ~Th7~) Ms Cheryl Scarlett Inquiry Secretary House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres StraitIslander Affairs Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Ms Scariett I thank the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Tones Strait Islander Affairs (the Committee) for the opportunity to contribute to its inquiry into Indigenous employment. As requested, here are the responses from the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (the Department) to the questions on notice that arose duringthe 6 February Public Hearing of the Committee. Question I — Report on Indleenous Employment in RuralIndustries The initial question on notice asked by the Committee was regarding a report by the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics (ABARE) on Indigenous employment in rural industries. I am now in a position to confirm that ABARE is expecting to publish this report by 31 March2006 on its website (w~vw abare. ~ov.au) Question 2 — FarmBis Statistics The second piece of information requested by the Committee was a State and Territory breakdown of Indigenous people’s participation in FarmBis programs. This information has been collated and is included at Enclosure 1 Question 3 — Tiwi IslandsForestry The Committee requested more specific information relating to the involvement of the Tiwi Island Community in Department’s National Indigenous Forestry Strategy. The Tiwi Forestry Project is a partnership between Great Southern Plantations Limitedand the Tiwi Land Council. The Tiwi Land Council was established in 1978, under the AboriginalLand Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth), and represents the Tiwi people who hold inalienable freehold title to their land under the Act. -

Rare Books Lib

RBTH 2239 RARE BOOKS LIB. S The University of Sydney Copyright and use of this thesis This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copynght Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act gran~s the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author's moral rights if you: • fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work • attribute this thesis to another author • subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author's reputation For further information contact the University's Director of Copyright Services Telephone: 02 9351 2991 e-mail: [email protected] Camels, Ships and Trains: Translation Across the 'Indian Archipelago,' 1860- 1930 Samia Khatun A thesis submitted in fuUUment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History, University of Sydney March 2012 I Abstract In this thesis I pose the questions: What if historians of the Australian region began to read materials that are not in English? What places become visible beyond the territorial definitions of British settler colony and 'White Australia'? What past geographies could we reconstruct through historical prose? From the 1860s there emerged a circuit of camels, ships and trains connecting Australian deserts to the Indian Ocean world and British Indian ports. -

Visitor Responses to Palm Island in the 1920S and 1930S1

‘Socialist paradise’ or ‘inhospitable island’? Visitor responses to Palm Island in the 1920s and 1930s1 Toby Martin Tourists visiting Queensland’s Palm Island in the 1920s and 1930s followed a well-beaten path. They were ferried there in a launch, either from a larger passenger ship moored in deeper water, or from Townsville on the mainland. Having made it to the shallows, tourists would be carried ‘pick a back’ by a ‘native’ onto a ‘palm-shaded’ beach. Once on the grassy plains that stood back from the beach, they would be treated to performances such as corroborees, war dances and spear-throwing. They were also shown the efforts of the island’s administration: schools full of happy children, hospitals brimming with bonny babies, brass band performances and neat, tree-fringed streets with European- style gardens. Before being piggy-backed to their launches, the tourist could purchase authentic souvenirs, such as boomerangs and shields. As the ship pulled away from paradise, tourists could gaze back and reflect on this model Aboriginal settlement, its impressive ‘native displays’, its ‘efficient management’ and the ‘noble work’ of its staff and missionaries.2 By the early 1920s, the Palm Island Aboriginal reserve had become a major Queensland tourist destination. It offered tourists – particularly those from the southern states or from overseas – a chance to see Aboriginal people and culture as part of a comfortable day trip. Travellers to and around Australia had taken a keen interest in Aboriginal culture and its artefacts since Captain Cook commented on the ‘rage for curiosities amongst his crew’.3 From the 1880s, missions such as Lake Tyers in Victoria’s Gippsland region had attracted 1 This research was undertaken with the generous support of the State Library of NSW David Scott Mitchell Fellowship, and the ‘Touring the Past: History and Tourism in Australia 1850-2010’ ARC grant, with Richard White.