Our Knowledge for Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

19 Language Revitalisation: Community and School Programs Working Together

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship 19 Language revitalisation: community and school programs working together Diane McNaboe1 and Susan Poetsch2 Abstract Since it was published in 2003 the New South Wales Aboriginal Languages K– 10 Syllabus has led to a substantial increase in the number of school programs operating in the state. It has supported the quality of those programs, and the status and recognition given to Aboriginal languages and cultures in the curriculum. School programs also complement community initiatives to revitalise, strengthen and share Aboriginal languages in New South Wales. As linguistic and cultural knowledge increases among adult community members, school programs provide a channel for them to continue to develop their own skills and knowledge and to pass on this heritage. This paper takes Wiradjuri as an example of language revitalisation, and describes achievements in adult language learning and the process of developing a school program with strong input from community. A brief history of Wiradjuri language revitalisation Wiradjuri is one of the central inland New South Wales (NSW) languages (Wafer & Lissarrague 2008, pp. 215–25). In recent decades various language teams have investigated and analysed archival sources for Wiradjuri and collected information from both written and oral sources (Büchli 2006, pp. 58–60). These teams include Grant and Rudder (2001a, b, c, d; 2005), Hosking and McNicol (1993), McNicol and Hosking (1994) and Donaldson (1984), as well as Christopher Kirkbright, George Fisher and Cheryl Riley, who have been working with Wiradjuri people in and near Sydney. -

Contents What’S New

September / October, No. 5/2011 CONTENTS WHAT’S NEW Two Suggestions About How To Make Cultural Heritage Win a free registration to the Materials Available .................................................................... 2 2012 Native Title Conference! Workshop Series: Thresholds for Traditional Owner Settlements in Victoria .............................................................. 4 Just take 5 minutes to complete our publications survey and you will go into the Foundations of the Kimberley Aboriginal Caring for Country Plan — Bungarun and the Kimberley Aboriginal Reference draw to win a free registration to the 2012 Group .......................................................................................... 5 Native Title Conference. The winner will be announced in January, 2012. ‘Anthropologies of Change: Theoretical and Methodological Challenges’ Workshop .............................................................. 8 CLICK HERE TO COMPLETE THE From Mississippi to Broome – Creating Transformative SURVEY Indigenous Economic Opportunity ........................................ 10 What’s New ............................................................................... 11 If you have any questions or concerns, please Native Title Publications ......................................................... 19 contact Matt O’Rourke at the Native Title Research Unit on (02) 6246 1158 or Native Title in the News ........................................................... 19 [email protected] Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUAs) -

Ngaanyatjarra Central Ranges Indigenous Protected Area

PLAN OF MANAGEMENT for the NGAANYATJARRA LANDS INDIGENOUS PROTECTED AREA Ngaanyatjarra Council Land Management Unit August 2002 PLAN OF MANAGEMENT for the Ngaanyatjarra Lands Indigenous Protected Area Prepared by: Keith Noble People & Ecology on behalf of the: Ngaanyatjarra Land Management Unit August 2002 i Table of Contents Notes on Yarnangu Orthography .................................................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgements........................................................................................................................................................ v Cover photos .................................................................................................................................................................. v Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................................. v Summary.................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................................................... -

Re-Awakening Languages: Theory and Practice in the Revitalisation Of

RE-AWAKENING LANGUAGES Theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages Edited by John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch and Michael Walsh Copyright Published 2010 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS University of Sydney Library sydney.edu.au/sup © John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch & Michael Walsh 2010 © Individual contributors 2010 © Sydney University Press 2010 Reproduction and Communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library F03 University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Readers are advised that protocols can exist in Indigenous Australian communities against speaking names and displaying images of the deceased. Please check with local Indigenous Elders before using this publication in their communities. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Re-awakening languages: theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages / edited by John Hobson … [et al.] ISBN: 9781920899554 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Languages--Revival. Australian languages--Social aspects. Language obsolescence--Australia. Language revival--Australia. iv Copyright Language planning--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Hobson, John Robert, 1958- Lowe, Kevin Connolly, 1952- Poetsch, Susan Patricia, 1966- Walsh, Michael James, 1948- Dewey Number: 499.15 Cover image: ‘Wiradjuri Water Symbols 1’, drawing by Lynette Riley. Water symbols represent a foundation requirement for all to be sustainable in their environment. -

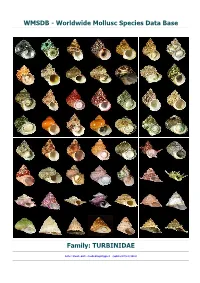

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: VETIGASTROPODA-TROCHOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINIDAE Rafinesque, 1815 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=681, Genus=26, Subgenus=17, Species=203, Subspecies=23, Synonyms=411, Images=168 abyssorum , Bolma henica abyssorum M.M. Schepman, 1908 aculeata , Guildfordia aculeata S. Kosuge, 1979 aculeatus , Turbo aculeatus T. Allan, 1818 - syn of: Epitonium muricatum (A. Risso, 1826) acutangulus, Turbo acutangulus C. Linnaeus, 1758 acutus , Turbo acutus E. Donovan, 1804 - syn of: Turbonilla acuta (E. Donovan, 1804) aegyptius , Turbo aegyptius J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Rubritrochus declivis (P. Forsskål in C. Niebuhr, 1775) aereus , Turbo aereus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) aethiops , Turbo aethiops J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Diloma aethiops (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) agonistes , Turbo agonistes W.H. Dall & W.H. Ochsner, 1928 - syn of: Turbo scitulus (W.H. Dall, 1919) albidus , Turbo albidus F. Kanmacher, 1798 - syn of: Graphis albida (F. Kanmacher, 1798) albocinctus , Turbo albocinctus J.H.F. Link, 1807 - syn of: Littorina saxatilis (A.G. Olivi, 1792) albofasciatus , Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albofasciatus , Marmarostoma albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 - syn of: Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albulus , Turbo albulus O. Fabricius, 1780 - syn of: Menestho albula (O. Fabricius, 1780) albus , Turbo albus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) albus, Turbo albus T. Pennant, 1777 amabilis , Turbo amabilis H. Ozaki, 1954 - syn of: Bolma guttata (A. Adams, 1863) americanum , Lithopoma americanum (J.F. -

Coober Pedy, South Australia

The etymology of Coober Pedy, South Australia Petter Naessan The aim of this paper is to outline and assess the diverging etymologies of ‘Coober Pedy’ in northern South Australia, in the search for original and post-contact local Indigenous significance associated with the name and the region. At the interface of contemporary Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara opinion (mainly in the Coober Pedy region, where I have conducted fieldwork since 1999) and other sources, an interesting picture emerges: in the current use by Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara people as well as non-Indigenous people in Coober Pedy, the name ‘Coober Pedy’ – as ‘white man’s hole (in the ground)’ – does not seem to reflect or point toward a pre-contact Indigenous presence. Coober Pedy is an opal mining and tourist town with a total population of about 3500, situated near the Stuart Highway, about 850 kilometres north of Adelaide, South Australia. Coober Pedy is close to the Stuart Range, lies within the Arckaringa Basin and is near the border of the Great Victoria Desert. Low spinifex grasslands amounts for most of the sparse vegetation. The Coober Pedy and Oodnadatta region is characterised by dwarf shrubland and tussock grassland. Further north and northwest, low open shrub savanna and open shrub woodland dominates.1 Coober Pedy and surrounding regions are arid and exhibit very unpredictable rainfall. Much of the economic activity in the region (as well as the initial settlement of Euro-Australian invaders) is directly related to the geology, namely quite large deposits of opal. The area was only settled by non-Indigenous people after 1915 when opal was uncovered but traditionally the Indigenous population was western Arabana (Midlaliri). -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

Management Plan for Recreational Fishing in South Australia

Management Plan for Recreational Fishing in South Australia August 2020 Information current as of 14 August 2020 © Government of South Australia 2020 Disclaimer PIRSA and its employees do not warrant or make any representation regarding the use, or results of the use, of the information contained herein as regards to its correctness, accuracy, reliability and currency or otherwise. PIRSA and its employees expressly disclaim all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or advice. All enquiries Primary Industries and Regions SA (PIRSA) Level 15, 25 Grenfell Street GPO Box 1671, Adelaide SA 5001 T: 08 8226 0900 E: [email protected] - 2 - Table of Contents 1 Fishery to which this plan applies ................................................................................. 5 2 Consistency with other management plans .................................................................. 5 3 Term of the plan and review of the plan ........................................................................ 6 4 Fisheries management in South Australia .................................................................... 6 5 Description of the fishery .............................................................................................. 7 5.1 Biological and environmental characteristics .......................................................... 9 5.2 Biology of key recreational species ....................................................................... 11 5.3 Social and economic characteristics .................................................................... -

(Pristis Microdon) in the Fitzroy River Kimberley,, Westernn Australia

Biology and cultural significance of the freshwater sawfish (Pristis microdon) in the Fitzroy River Kimberley, Western Australia Report to 2004 A collaboration between Kimberley Language Resource Centre Cover Artwork: Competition winner, freshwater sawfish painting by Joy Nuggett (Mangkaja Arts, Fitzroy Crossing, Western Australia) Report by Dean Thorburn, David Morgan and Howard Gill from the Freshwater Fish Group at the Centre for Fish & Fisheries Research Mel Johnson, Hugh Wallace-Smith, Tom Vigilante, Ari Gorring, Ishmal Croft and Jean Fenton Land + Sea Unit Numerous language experts and people of the west Kimberley in conjunction with the Kimberley Language Resource Centre Our sincere gratitude is extended to the Threatened Species Network and World Wide Fund For Nature for providing the funds for this project. Fishcare WA and Environment Australia also made a substantial financial contribution to the project . 2 Project Summary During a collaborative study involving researchers and members from Murdoch University, the Kimberley Land Council, the Kimberley Language Resource Centre and numerous communities of the west Kimberley, a total of 79 endangered freshwater sawfish Pristis microdon were captured (and released) from King Sound and the Fitzroy, May and Robinson rivers between 2002 and 2004. Forty of these individuals were tagged. This culturally significant species, is not only an important food source, but is included in a number of stories and beliefs of the peoples of the Fitzroy River, where it is referred to as ‘galwanyi’ in Bunuba and Gooniyandi, ‘wirridanyniny’ or ‘pial pial’ in Nyikina, and ‘wirrdani’ in Walmajarri (see Chapter 2). In relation to the biology and ecology of the species (Chapter 1), of the 73 individuals sexed, 43 were female, ranging in length from 832 to 2770 mm TL, and 30 were male, ranging in length from 815 to 2350 mm TL. -

A Grammatical Sketch of Ngarla: a Language of Western Australia Torbjörn Westerlund

UPPSALA UNIVERSITY master thesis The department for linguistics and philology spring term 2007 A grammatical sketch of Ngarla: A language of Western Australia Torbjörn Westerlund Supervisor: Anju Saxena Abstract In this thesis the basic grammatical structure of normal speech style of the Western Australian language Ngarla is described using example sentences taken from the Ngarla – English Dictionary (by Geytenbeek; unpublished). No previous description of the language exists, and since there are only five people who still speak it, it is of utmost importance that it is investigated and described. The analysis in this thesis has been made by Torbjörn Westerlund, and the focus lies on the morphology of the nominal word class. The preliminary results show that the language shares many grammatical traits with other Australian languages, e.g. the ergative/absolutive case marking pattern. The language also appears to have an extensive verbal inflectional system, and many verbalisers. 2 Abbreviations 0 zero marked morpheme 1 first person 1DU first person dual 1PL first person plural 1SG first person singular 2 second person 2DU second person dual 2PL second person plural 2SG second person singular 3 third person 3DU third person dual 3PL third person plural 3SG third person singular A the transitive subject ABL ablative ACC accusative ALL/ALL2 allative ASP aspect marker BUFF buffer morpheme C consonant CAUS causative COM comitative DAT dative DEM demonstrative DU dual EMPH emphatic marker ERG ergative EXCL exclusive, excluding addressee FACT factitive FUT future tense HORT hortative ImmPAST immediate past IMP imperative INCHO inchoative INCL inclusive, including addressee INSTR instrumental LOC locative NEG negation NMLISER nominaliser NOM nominative N.SUFF nominal class suffix OBSCRD obscured perception P the transitive object p.c. -

North West Wiradjuri Language and Culture Nest Stage 1 Final Report

North West Wiradjuri Language and Culture Nest Stage 1 Final Report Prepared for participating Aboriginal Communities and members of the North West Wiradjuri Language and Culture Nest Reference Group June 2018 Ilan Katz, Jan Idle, Shona Bates, Wendy Jopson, Michael Barnes This report belongs to the Aboriginal Communities of Dubbo, Narromine, Gilgandra, Peak Hill, Trangie, Wellington and Mudgee, and the North West Wiradjuri Language and Culture Nest Reference Group. The North West Wiradjuri Language and Culture Nest operates on Wiradjuri Country. The evaluation team from the Social Policy Research Centre acknowledges the Wiradjuri peoples as the traditional custodians of the land we work on and pay our respect to Elders past, present and future and all Aboriginal peoples in the region. Acknowledgements We thank Aboriginal Communities involved for their support and participation in this evaluation. We would like to thank Tony Dreise and Dr Lynette Riley – both members of the Evaluation Steering Committee – for reviewing the report. The OCHRE Evaluation was funded by Aboriginal Affairs NSW. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and may not reflect those of Aboriginal Affairs NSW or the New South Wales Government. We would like to acknowledge the contribution of Aboriginal Affairs NSW for their support. Evaluation Team Prof Ilan Katz, Michael Barnes, Shona Bates, Dr Jan Idle, Wendy Jopson, Dr BJ Newton For further information: Ilan Katz +61 2 9385 7800 Social Policy Research Centre UNSW Sydney NSW 2052 Australia T +61 2 9385 7800 F +61 2 9385 7838 E [email protected] W www.sprc.unsw.edu.au © UNSW Australia 2018 The Social Policy Research Centre is based in the Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences at UNSW Sydney. -

![AR Radcliffe-Brown]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4080/ar-radcliffe-brown-684080.webp)

AR Radcliffe-Brown]

P129: The Personal Archives of Alfred Reginald RADCLIFFE-BROWN (1881- 1955), Professor of Anthropology 1926 – 1931 Contents Date Range: 1915-1951 Shelf Metre: 0.16 Accession: Series 2: Gift and deposit register p162 Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown was born on 17 January 1881 at Aston, Warwickshire, England, second son of Alfred Brown, manufacturer's clerk and his wife Hannah, nee Radcliffe. He was educated at King Edward's School, Birmingham, and Trinity College, Cambridge (B.A. 1905, M. A. 1909), graduating with first class honours in the moral sciences tripos. He studied psychology under W. H. R. Rivers, who, with A. C. Haddon, led him towards social anthropology. Elected Anthony Wilkin student in ethnology in 1906 (and 1909), he spent two years in the field in the Andaman Islands. A fellow of Trinity (1908 - 1914), he lectured twice a week on ethnology at the London School of Economics and visited Paris where he met Emily Durkheim. At Cambridge on 19 April 1910 he married Winifred Marie Lyon; they were divorced in 1938. Radcliffe-Brown (then known as AR Brown) joined E. L. Grant Watson and Daisy Bates in an expedition to the North-West of Western Australia studying the remnants of Aboriginal tribes for some two years from 1910, but friction developed between Brown and Mrs. Bates. Brown published his research from that time in an article titled “Three Tribes of Western Australia”, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 43, (Jan. - Jun., 1913), pp. 143-194. At the 1914 meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Melbourne, Daisy Bates accused Brown of gross plagiarism.