Coober Pedy, South Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ngaanyatjarra Central Ranges Indigenous Protected Area

PLAN OF MANAGEMENT for the NGAANYATJARRA LANDS INDIGENOUS PROTECTED AREA Ngaanyatjarra Council Land Management Unit August 2002 PLAN OF MANAGEMENT for the Ngaanyatjarra Lands Indigenous Protected Area Prepared by: Keith Noble People & Ecology on behalf of the: Ngaanyatjarra Land Management Unit August 2002 i Table of Contents Notes on Yarnangu Orthography .................................................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgements........................................................................................................................................................ v Cover photos .................................................................................................................................................................. v Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................................. v Summary.................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................................................... -

Indigenous Design Issuesceduna Aboriginal Children and Family

INDIGENOUS DESIGN ISSUES: CEDUNA ABORIGINAL CHILDREN AND FAMILY CENTRE ___________________________________________________________________________________ 1 INDIGENOUS DESIGN ISSUES: CEDUNA ABORIGINAL CHILDREN AND FAMILY CENTRE ___________________________________________________________________________________ 2 INDIGENOUS DESIGN ISSUES: CEDUNA ABORIGINAL CHILDREN AND FAMILY CENTRE ___________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .................................................................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWELDGEMENTS............................................................................................................ 5 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 5 PART 1: PRECEDENTS AND “BEST PRACTICE„ DESIGN ....................................................10 The Design of Early Learning, Child-care and Children and Family Centres for Aboriginal People ..................................................................................................................................10 Conceptions of Quality ........................................................................................................ 10 Precedents: Pre-Schools, Kindergartens, Child and Family Centres ..................................12 Kulai Aboriginal Preschool ............................................................................................. -

EARLY COOBER PEDY SHOW HOME/DUGOUT - for SALE Coober Pedy Is a Town Steeped in the Rich History of Early Opal Mining and Its Related Industry Tourism

ISSN 1833-1831 Tel: 08 8672 5920 http://cooberpedyregionaltimes.wordpress.com Thursday 19 May 2016 EARLY COOBER PEDY SHOW HOME/DUGOUT - FOR SALE Coober Pedy is a town steeped in the rich history of early opal mining and its related industry tourism. The buying and selling of dugouts is a way of life in the Opal Capital of the World where the majority of family homes are subterranean. A strong real-estate presence has always been evident in Coober Pedy, but opal mining family John and Jerlyn Nathan with their two daughters are self-selling their historic dugout in order to buy an acreage just out of town that will suit their growing family’s needs better. The Nathan family currently live on the edge of town, a few minutes from the school and not far from the shops. Despite they brag one of most historic homes around with a position and a view from the east side of North West Ridge to be envied, John tells us that his growing family needs more space outside. “Prospector’s Dugout has plenty of space inside, with 4 bedrooms plus,” said John. “But the girls have grown in 5 years and we have an opportunity, once this property is sold, to buy an acreage outside of town, and where my daughters can have a trail bike and other outdoor activities where it won’t bother anyone.” “I will regret relinquishing our location and view but I think kids need the freedom of the outdoors when they are growing up,’ he said. John and Jeryln bought the 1920’s dugout at 720 Russell John and Jerlyn Nathan with daughters De’ Arna and Darna on the patio at Prospector’s Dugout. -

Introduction

This item is Chapter 1 of Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus Editors: Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson ISBN 978-0-728-60406-3 http://www.elpublishing.org/book/language-land-and-song Introduction Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson Cite this item: Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson (2016). Introduction. In Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus, edited by Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson. London: EL Publishing. pp. 1-22 Link to this item: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/2001 __________________________________________________ This electronic version first published: March 2017 © 2016 Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing Open access, peer-reviewed electronic and print journals, multimedia, and monographs on documentation and support of endangered languages, including theory and practice of language documentation, language description, sociolinguistics, language policy, and language revitalisation. For more EL Publishing items, see http://www.elpublishing.org 1 Introduction Harold Koch,1 Peter K. Austin 2 & Jane Simpson 1 Australian National University1 & SOAS University of London 2 1. Introduction Language, land and song are closely entwined for most pre-industrial societies, whether the fishing and farming economies of Homeric Greece, or the raiding, mercenary and farming economies of the Norse, or the hunter- gatherer economies of Australia. Documenting a language is now seen as incomplete unless documenting place, story and song forms part of it. This book presents language documentation in its broadest sense in the Australian context, also giving a view of the documentation of Australian Aboriginal languages over time.1 In doing so, we celebrate the achievements of a pioneer in this field, Luise Hercus, who has documented languages, land, song and story in Australia over more than fifty years. -

MARLA-OODNADATTA DISTRICT PROFILE: Characteristics4 and Challenges1,2

MARLA-OODNADATTA DISTRICT PROFILE: Characteristics4 and challenges1,2 South Australian Arid Lands NRM region Marla ABOUT THE MARLA- Oodnadatta OODNADATTA DISTRICT Algebuckina Innamincka Moomba The Marla-Oodnadatta Marla-Oodnadatta Marree-Innamincka district covers an area of Anna Creek approximately 132,000 Coober Pedy square kilometres (12% Coward Springs of South Australia in Curdimurka the north-west pastoral Marree region and is bounded Arkaroola Village Kingoonya by the Simpson Desert Andamooka Tarcoola Roxby Downs Leigh Creek and Lake Eyre to the Kingoonya Glendambo North Flinders Ranges east, the Great Victoria Woomera Desert to the west and Parachilna the Northern Territory border to the north. Hawker Gawler Ranges Legend North East Olary Port Augusta Iron Knob Waterways and Lakes Yunta Iron Baron National Parks and Reserves Whyalla Dog Fence COMMUNITIES VEGETATION WATER The permanent population of the district Major vegetation types include: The Great Artesian Basin provides an is approximately 2,000 people. Townships Plains: Mitchell grass, glassworts, poverty important source of water within the include Coober Pedy, Marla, Oodnadatta bush, saltbush, cannonball, neverfail, district. Natural venting occurs in the form and William Creek. bluebush, sea heath, samphire, twiggy sida, of mound springs, found predominately cottonbush, copper burr, pigface, prickly near the Oodnadatta Track. Waterholes CLIMATE wattle, mulga, lignum, cane grass. are found along major and minor drainage lines, some with the capacity to hold water The climate of the district is very arid Sandplains: Mulga, senna, marpoo, emu for over 12 months. with hot to extremely hot summers and bush, woollybutt, sandhill canegrass, mild, dry winters. Average annual rainfall copper burr, corkwood, dead finish, ranges between 120mm to 210mm across bluebush, saltbush. -

Safety in Opal Mining Guide

Safety in Opal Mining Opal Miner’s Guide Coober Pedy Mine Rescue emergency phone number is 8672 5999. Andamooka Mine Rescue emergency phone numbers are (Police) 8672 7072, (Clinic) 8672 7087, (Post office) 8672 7007. Mintabie Mine Rescue emergency phone numbers are (clinic) 8670 5032, (SES) 8670 5162, 8670 5037 A.H. South Australia Opal Fields Disclaimer Information provided in this publication is designed to address the most commonly raised issues in the workplace relevant to South Australian legislation such as the Occupational Health Safety and Welfare Act 1986 and the Workers Rehabilitation and Compensation Act 1986. They are not intended as a replacement for the legislation. In particular, WorkCover Corporation, its agents, officers and employees : • make no representations, express or implied, as to the accuracy of the information and data contained in the publication, • accept no liability for any use of the said information or reliance placed on it, and make no representations, either expressed or implied, as to the suitability of the said information for any particular purpose. Awards recognition 1999 S.A Resources Industry Awards. Judges Citation for Safety Culture Development Awarded to Safety in Opal Mining Project. ISBN: 0 9585938 5 X Cover: Opals. Black Opals Majestic Opals Safety in Opal Mining Opal miner’s guide A South Australian Project. Funded by: The Mining and Quarrying Occupational Health and Safety Committee. Project Officer: Sophia Provatidis. With input from the miners of Coober Pedy, Mintabie, Andamooka and Lambina. -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

A Preliminary Study of Pitch and Rhythm in Pitjantjatjara

A PRELIMINARY STUDY OF PITCH AND RHYTHM IN PITJANTJATJARA. Marija Tabain (La Trobe University, Melbourne), Janet Fletcher (University of Melbourne), Christian Heinrich (Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich) Pitjantjatjara is a dialect of the greater Western Desert language, spoken mainly in the north-west of South Australia, but extending north into the Northern Territory, and west into Western Australia (Douglas 1964). Like most Australian languages, Pitjantjatjara has been analysed as a stress language (trochaic); however relatively little is known about the intonational system of this language. We present a preliminary analysis of the prosodic structure of Pitjantjatjara based on three female speakers reading two different texts – the Walpa Ulpariranya munu Tjintunya (South Wind and the Sun) passage, and the Nanikuta (Three Billy Goats) text. Our first result suggests that the shape and temporal alignment of major pitch movements perform a largely demarcative function, aligning with the metrically strong first syllable in a word. There is mixed evidence, however, that strong syllables are longer or have more "peripheral" vowels: differences in strong vs. weak syllable duration are text- dependent, while the formant patterns for the three vowel phonemes /i, a, u/ suggest subtle formant differences, rather than categorical changes in vowel quality, according to strong vs. weak syllable. We also consider the traditional rhythm metrics (e.g. vocalic nPVI and intervocalic rPVI). These suggest that Pitjantjatjara is a stress-based language. However, as noted above, Pitjantjatjara does not have vowel reduction in weak syllables, and in addition, it has a predominantly CV syllable structure. Moreover, Australian languages such as Pitjantjatjara have a high proportion of sonorants in their phoneme inventory (Butcher 2006), and despite the mainly CV syllable structure, sonorant coda consonants are possible and not infrequent. -

Management Plan for Recreational Fishing in South Australia

Management Plan for Recreational Fishing in South Australia August 2020 Information current as of 14 August 2020 © Government of South Australia 2020 Disclaimer PIRSA and its employees do not warrant or make any representation regarding the use, or results of the use, of the information contained herein as regards to its correctness, accuracy, reliability and currency or otherwise. PIRSA and its employees expressly disclaim all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or advice. All enquiries Primary Industries and Regions SA (PIRSA) Level 15, 25 Grenfell Street GPO Box 1671, Adelaide SA 5001 T: 08 8226 0900 E: [email protected] - 2 - Table of Contents 1 Fishery to which this plan applies ................................................................................. 5 2 Consistency with other management plans .................................................................. 5 3 Term of the plan and review of the plan ........................................................................ 6 4 Fisheries management in South Australia .................................................................... 6 5 Description of the fishery .............................................................................................. 7 5.1 Biological and environmental characteristics .......................................................... 9 5.2 Biology of key recreational species ....................................................................... 11 5.3 Social and economic characteristics .................................................................... -

Qantas Domestic Australia Route Network

Qantas Domestic Route Network Effective 1 October 2018. Routes shown are indicative only 08:00 ARAFURA SEA 09:30 Thursday Island HORN ISLAND 10:00 Melville Island Maningrida GOVE (Nhulunbuy) DARWIN Oenpelli Jabiru ARNHEM WEIPA LAND Batchelor KAKADU CAPE GREAT Daly River Pine Creek Coen TIMOR SEA Groote Eylandt YORK Kalumburu Wadeye Katherine Ngukurr Gulf of PENINSULA CORAL Oombulgurri Carpentaria Wyndham Laura Cooktown SEA KIMBERLEY KUNUNURRA Borroloola Daly Waters MCARTHUR Mossman RIVER Port Douglas Mareeba Mungana CAIRNS Derby Newcastle Waters I NDIAN Kalkarindji Karumba Atherton BARRIER Normanton Burketown Tully BROOME Croydon OCEAN Halls Creek NORTHERN Doomadgee Georgetown Forsayth Ingham GULF TERRITORY TOWNSVILLE COUNTRY Tennant Creek Ayr Tanami Camooweal Kajabbi Bowen Charters Towers HAMILTON ISLAND PORT HEDLAND Julia Creek PROSERPINE Dampier GREAT SANDY DESERT MT ISA KARRATHA CLONCURRY Richmond Hughenden Marble Bar MACKAY REEF GREAT Onslow Barrow Creek Exmouth Pannawonica Telfer Dajarra QUEENSLAND LEARMONTH Solomon MORANBAH PILBARA Winton Saraji Tom Price Blair Athol Boulia Yeppoon PARABURDOO NEWMAN GIBSON DESERT EMERALD Jigalong ALICE SPRINGS LONGREACH Blackwater ROCKHAMPTON BARCALDINE GLADSTONE Areyonga CHANNEL Springsure Bedourie Biloela BLACKALL DIVIDING Moura Carnarvon Kaltukatjara Yaraka Monto BUNDABERG COUNTRY Theodore ULURU HERVEY BAY WESTERN Uluru Windorah Maryborough Finke SIMPSON DESERT Gayndah Birdsville Augathella Injune Warburton AUSTRALIA Amata Ernabella Gympie CHARLEVILLE Noosa Meekatharra ROMA Kingaroy Wiluna Quilpie -

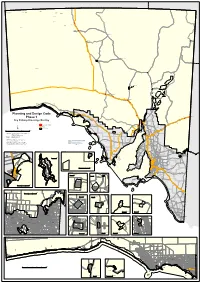

Key Railway Crossings Overlay 113411.4 94795 ! Port Augusta ! !

N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y Amata ! Kalka Kanpi ! ! Nyapari Pipalyatjara ! ! Pukatja ! Yunyarinyi ! Umuwa ! QUEENSLAND Kaltjiti ! !113411.4 94795 Indulkana ! Mimili ! Watarru ! 113411.4 94795 Mintabie ! ! ! Marla Oodnadatta ! Innamincka Cadney Park ! ! Moomba ! WESTERN AUSTRALIA William Creek ! Coober Pedy ! Oak Valley ! Marree ! ! Lyndhurst Arkaroola ! Andamooka ! Roxby Downs ! Copley ! ! Nepabunna Leigh Creek ! Tarcoola ! Beltana ! 113411.4 94795 !! 113411.4 94795 Kingoonya ! Glendambo !113411.4 94795 Parachilna ! ! Blinman ! Woomera !!113411.4 94795 Pimba !113411.4 94795 Nullarbor Roadhouse Yalata ! ! ! Wilpena Border ! Village ! Nundroo Bookabie ! Coorabie ! Penong ! NEW SOUTH WALES ! Fowlers Bay FLINDERS RANGES !113411.4 94795 Planning and Design Code ! 113411.4 94795 ! Ceduna CEDUNA Cockburn Mingary !113411.4 94795 ! ! Phase 1 !113411.4 94795 Olary ! Key Railway Crossings Overlay 113411.4 94795 ! Port Augusta ! ! !113411.4 94795 Manna Hill ! STREAKY BAY Key Railway Crossings Yunta ! Iron Knob Railway MOUNT REMARKABLE ± Phase 1 extent PETERBOROUGH 0 50 100 150 km Iron Baron ! !!115768.8 17888 WUDINNA WHYALLA KIMBA Whyalla Produced by Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure Development Division ! GPO Box 1815 Adelaide SA 5001 Port Pirie www.sa.gov.au NORTHERN Projection Lambert Conformal Conic AREAS Compiled 11 January 2019 © Government of South Australia 2019 FRANKLIN No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted PORT in any form, or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, HARBOUR Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure. PIRIE ELLISTON CLEVE While every reasonable effort has been made to ensure that this document is correct at GOYDER the time of publication, the State of South Australia and its agencies, instrumentalities, employees and contractors disclaim any and all liability to any person in respect to anything or the consequence of anything done or omitted to be done in reliance upon the whole or any part of this document. -

Native Title Groups from Across the State Meet

Aboriginal Way www.nativetitlesa.org Issue 69, Summer 2018 A publication of South Australian Native Title Services Above: Dean Ah Chee at a co-managed cultural burn at Witjira NP. Read full article on page 6. Native title groups from across the state meet There are a range of support services Nadja Mack, Advisor at the Land Branch “This is particularly important because PBC representatives attending heard and funding options available to of the Department and Prime Minister the native title landscape is changing… from a range of organisations that native title holder groups to help and Cabinet (PM&C) told representatives we now have more land subject to offer support and advocacy for their them on their journey to become from PBCs present that a 2016 determination than claims, so about organisations, including SA Native independent and sustainable consultation had led her department to 350 determinations and 240 claims, Title Services (SANTS), the Indigenous organisations that can contribute currently in Australia. focus on giving PBCs better access to Land Corporation (ILC), Department significantly to their communities. information, training and expertise; on “We have 180 PBCs Australia wide, in of Environment Water and Natural That was the message to a forum of increasing transparency and minimising South Australia 15 and soon 16, there’s Resources (DEWNR), AIATSIS, Indigenous South Australian Prescribed Bodies disputes within PBCs; on providing an estimate that by 2025 there will be Business Australia (IBA), Office of the Corporate (PBCs) held in Adelaide focussed support by native title service about 270 – 290 PBCs Australia wide” Registrar of Indigenous Corporations recently.