SEVEN WOMEN of the 1967 REFERENDUM Project For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of NAIDOC Celebrating Indigenous Culture

The History of NAIDOC Celebrating Indigenous Culture latrobe.edu.au CRICOS Provider 00115M Wominjeka Welcome La Trobe University 22 Acknowledgement La Trobe University acknowledges the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nations as the traditional custodians of the land upon which the Bundoora campus is located. LaLa Trobe Trobe University University 33 Acknowledgement We recognise their ongoing connection to the land and value the unique contribution the Wurundjeri people and all Indigenous Australians make to the University and the wider Australian society. LaLa Trobe Trobe University University 44 What is NAIDOC? NAIDOC stands for the ‘National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee’. This committee was responsible for organising national activities during NAIDOC Week and its acronym has since become the name of the week itself. La Trobe University 55 History of NAIDOC NAIDOC Week celebrations are held across Australia each July to celebrate the history, culture and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. NAIDOC is celebrated not only in Indigenous communities, but by Australians from all walks of life. La Trobe University 66 History of NAIDOC 1920-1930 Before the 1920s, Aboriginal rights groups boycotted Australia Day (26 January) in protest against the status and treatment of Indigenous Australians. Several organisations emerged to fill this role, particularly the Australian Aborigines Progressive Association (AAPA) in 1924 and the Australian Aborigines League (AAL) in 1932. La Trobe University 77 History of NAIDOC 1930’s In 1935, William Cooper, founder of the AAL, drafted a petition to send to King George V, asking for special Aboriginal electorates in Federal Parliament. The Australian Government believed that the petition fell outside its constitutional Responsibilities William Cooper (c. -

AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY a Series That Profiles Some of the Most Extraordinary Australians of Our Time

STUDY GUIDE AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY A series that profiles some of the most extraordinary Australians of our time F aith Bandler 1920–2015 Civi l Rights Activist This program is an episode of Australian Biography Series 2 produced under the National Interest Program of Film Australia. This well-established series profiles some of the most extraordinary Australians of our time. Many have had a major impact on the nation’s cultural, political and social life. All are remarkable and inspiring people who have reached a stage in their lives where they can look back and reflect. Through revealing in-depth interviews, they share their stories— of beginnings and challenges, landmarks and turning points. In so doing, they provide us with an invaluable archival record and a unique perspective on the roads we, as a country, have travelled. Australian Biography: Faith Bandler Director/Producer Frank Heimans Executive Producer Ron Saunders Duration 26 minutes Year 1993 © NFSA Also in Series 2: Franco Belgiorno-Nettis, Nancy Cato, Frank Hardy, Phillip Law, Dame Roma Mitchell, Elizabeth Riddell A FILM AUSTRALIA NATIONAL INTEREST PROGRAM For more information about Film Australia’s programs, contact: National Film and Sound Archive of Australia Sales and Distribution | PO Box 397 Pyrmont NSW 2009 T +61 2 8202 0144 | F +61 2 8202 0101 E: [email protected] | www.nfsa.gov.au AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY: FAITH BANDLER 2 SYNOPSIS How did the sugar industry benefit from the Islanders? What does this suggest about the relationship between labour and the success Faith Bandler is a descendant of South Sea Islanders. At the age of of industry? 13, her father was kidnapped from the island of Ambrym, in what Aside from unequal wages, what other issues of inequality arise is known as Vanuatu, and brought to Australia to work as an unpaid from the experiences of Islanders in Queensland? labourer in the Queensland cane fields. -

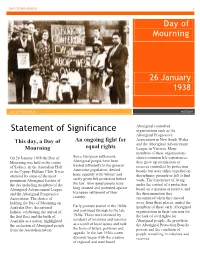

Day of Mourning – Overview Fact Sheet

DAY OF MOURNING 1 Day of Mourning 26 January 1938 DAY OF MOURNING HISTORY Aboriginal controlled Statement of Significance organisations such as the Aboriginal Progressive Association in New South Wales An ongoing fight for This day, a Day of and the Aboriginal Advancement Mourning equal rights League in Victoria. Many members of these organisations On 26 January 1938 the Day of Since European settlement, shared common life experiences; Mourning was held in the centre Aboriginal people have been they grew up on missions or of Sydney, in the Australian Hall treated differently to the general reserves controlled by protection at the Cyprus Hellene Club. It was Australian population; denied boards but were either expelled on attended by some of the most basic equality with 'whites' and disciplinary grounds or left to find prominent Aboriginal leaders of rarely given full protection before work. The experience of living the day including members of the the law. Aboriginal people have under the control of a protection Aboriginal Advancement League long resisted and protested against board on a mission or reserve, and and the Aboriginal Progressive European settlement of their the discrimination they Association. The choice of country. encountered when they moved holding the Day of Mourning on away from these places, united the Australia Day, the national Early protests started in the 1840s members of these early Aboriginal holiday celebrating the arrival of and continued through to the late organisations in their concerns for the first fleet and the birth of 1920s. These were initiated by the lack of civil rights for Australia as a nation, highlighted residents of missions and reserves Aboriginal people, the growth in the exclusion of Aboriginal people as a result of local issues and took the Aboriginal Protection Board's from the Australian nation. -

Golden Yearbook

Golden Yearbook Golden Yearbook Stories from graduates of the 1930s to the 1960s Foreword from the Vice-Chancellor and Principal ���������������������������������������������������������5 Message from the Chancellor ��������������������������������7 — Timeline of significant events at the University of Sydney �������������������������������������8 — The 1930s The Great Depression ������������������������������������������ 13 Graduates of the 1930s ���������������������������������������� 14 — The 1940s Australia at war ��������������������������������������������������� 21 Graduates of the 1940s ����������������������������������������22 — The 1950s Populate or perish ���������������������������������������������� 47 Graduates of the 1950s ����������������������������������������48 — The 1960s Activism and protest ������������������������������������������155 Graduates of the 1960s ���������������������������������������156 — What will tomorrow bring? ��������������������������������� 247 The University of Sydney today ���������������������������248 — Index ����������������������������������������������������������������250 Glossary ����������������������������������������������������������� 252 Produced by Marketing and Communications, the University of Sydney, December 2016. Disclaimer: The content of this publication includes edited versions of original contributions by University of Sydney alumni and relevant associated content produced by the University. The views and opinions expressed are those of the alumni contributors and do -

![Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Thursday, 19 February 2015] P412c-412C Hon Darren West](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5532/extract-from-hansard-council-thursday-19-february-2015-p412c-412c-hon-darren-west-705532.webp)

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Thursday, 19 February 2015] P412c-412C Hon Darren West

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Thursday, 19 February 2015] p412c-412c Hon Darren West FAITH BANDLER Statement HON DARREN WEST (Agricultural) [5.19 pm]: My statement will be brief. I rise this evening with a little sadness as I would like to address and share with the house the recent passing of Faith Bandler. Faith Bandler was born in Tumbulgum in New South Wales in 1918, the daughter of a Scottish–Indian mother and Peter Mussing, who had been blackbirded in 1883 from Ambrym Island, Vanuatu—known then as the New Hebrides. At 13 years of age he was sent to Mackay, Queensland to work on a sugarcane plantation. He escaped and married Faith Bandler’s mother. Faith Bandler cited stories of her father’s harsh experience as a slave labourer as a strong motivation for her activism. Her father died in 1924 when Faith was five. During World War II, Faith and her sister, Kath, served in the Australian Women’s Land Army. Indigenous women received less pay than white workers. After her discharge in 1945, she started a campaign for equal pay for Indigenous workers. In 1952, Faith married Hans Bandler, a Jewish refugee from Vienna. They had a daughter, Lilon Gretl, and fostered a son, Peter. In 1956, Faith became a full-time activist, becoming involved in the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, which was formed in 1957. During this period, Faith led the campaign for a constitutional referendum to remove discriminatory provisions from the Constitution of Australia. This campaign included petitions and public meetings, resulting in the 1967 referendum succeeding in all six states with 91 per cent support. -

Australian Indigenous Petitions

Australian Indigenous Petitions: Emergence and Negotiations of Indigenous Authorship and Writings Chiara Gamboz Dissertation Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences October 2012 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT 'l hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the proiect's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.' Signed 5 o/z COPYRIGHT STATEMENT 'l hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or digsertation in whole or part in the Univercity libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertiation. -

The Arts- Media Arts

Resource Guide The Arts- Media Arts The information and resources contained in this guide provide a platform for teachers and educators to consider how to effectively embed important ideas around reconciliation, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories, cultures and contributions, within the specific subject/learning area of The Arts- Media Arts. Please note that this guide is neither prescriptive nor exhaustive, and that users are encouraged to consult with their local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community, and critically evaluate resources, in engaging with the material contained in the guide. Page 2: Background and Introduction to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Media Arts Page 4: Timeline of Key Dates in the Contemporary History of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Media Arts Page 8: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Media Arts and Artists— Television Page 10: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Media Arts and Artists— Film Page 14: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Media Arts and Artists— Newspaper, Magazine and Comic Book Page 15: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Media Arts and Artists— Radio Page 17: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Media Arts and Artists— Apps, Interactive Animations and Video Games Page 19: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Media Arts and Artists—The Internet Page 21: Celebratory Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Media Arts Events Page 22: Other Online Guides/Reference Materials Page 23: Reflective Questions for Media Arts Staff and Students Please be aware this guide may contain references to names and works of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people that are now deceased. External links may also include names and images of those who are now deceased. -

A Personal Journey with Anangu History and Politics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Flinders Academic Commons FJHP – Volume 27 ‐2011 A Personal Journey with Anangu History and Politics Bill Edwards Introduction Fifty years ago, in September 1961, I sat in the shade of a mulga tree near the Officer Creek, a usually dry watercourse which rises in the Musgrave Ranges in the far north- west of South Australia and peters out in the sandhill country to the south. I was observing work being done to supply infrastructure for a new settlement for Pitjantjatjara/Yankunytjatjara Aboriginal people. That settlement, which opened in the following month of October, is Fregon, an Aboriginal community which together with other Pitjantjatjara/Yankunytjatjara communities featured in newspaper and radio news reports in September 2011. These reports referred to overcrowding in houses, the lack of adequate furnishings, poverty and, in the case of Fregon, children starving. Later comments by people on the ground suggested that the reports of starvation were exaggerated.1 When I returned to my home at Ernabella Mission, 60 kilometres north-east of Fregon, in 1961, I recorded my observations and forwarded them to The Advertiser in Adelaide. They were published as a feature article on Saturday 23 September, 1961 under the heading ‘Cattle Station for “Old Australians”’.2 As I read and listened to the recent reports I was concerned at the limited understanding of the history and the effects of policy changes in the region. As a letter I wrote to The Advertiser, referring back to my earlier article, was not published, I expanded it into an article and sent it to Nicolas Rothwell, the Northern Territory correspondent for The Australian, seeking his advice as to where I might submit it. -

ABORIGINAL HISTORY 1983 7:1 Top: Pearl Gibbs When Elected To

ABORIGINAL HISTORY 1983 7:1 Top: Pearl Gibbs when elected to N.S.W. Aborigines Welfare Board, 14 August 1954. Photograph courtesy o f Jack Homer. Bottom: Pearl Gibbs at Dubbo in August 1980. Photograph by Coral Edwards. 4 THREE TRIBUTES TO PEARL GIBBS (1901-1983) PEARL GIBBS: ABORIGINAL PATRIOT Kevin Gilbert Pearl Gibbs often described herself as ‘a battler’. Maybe, after a lifetime of battling the odds against white Australia, this description should be her epitaph. However neither that nor any other lauding of her fighting spirit would do her justice. Nothing short of justice, humanity and land rights for Aborigines could signify even a portion of the great love of this land that Pearl held. When I heard of her death I was assailed by emotion and guilt, self-recrimination for having deserted her at the end of her life, because her painful quest for Rights, Justice, Love, Humanity, International Covenants and love for Australia, our land, became too much for me to bear. A song I once sung, once wrote upon a poem, came back to mind: ‘She was of Kamilroi / a Princess in stature / a Goddess of nature / though only a child . .’ and, from a dimly recollected image a line from the Bible: ‘These are the heirs, come let us kill them that the inheritance will be ours’. There’ll be no epitaphs for Pearl In copperplate upon a stone No funeral of State or trace Of civic honor to remark Her passing though her feet have trod The Halls of Justice haunting God And man and woman child and fool Who makes the Nation’s Law a tool Of massacre and hate Injustice, land theft tortured fate Befall the rightful heirs their sons Must fall to strychnine and the guns The last descendants to imprisonment The will negated, overthrown The phantom killer called the Crown By Acts repeals the Right Of victims of its conquering lusts And holds the land by might. -

The Aboriginal Struggle & the Left

The Aboriginal Struggle & the Left Terry Townshend 2 The Aboriginal Struggle & the Left About the author Terry Townsend was a longtime member of the Democratic Socialist Party and now the Socialist Alliance. He edited the online journal Links (links.org) and has been a frequent contributor to Green Left Weekly (greenleft.org.au). Note on quotations For ease of reading, we have made minor stylistic changes to quotations to make their capitalisation consistent with the rest of the book. The exception, however, concerns Aborigines, Aboriginal, etc., the capitalisation of which has been left unchanged as it may have political significance. Resistance Books 2009 ISBN 978-1-876646-60-8 Published by Resistance Books, resistanceboks.com Contents Preface...........................................................................................................................5 Beginnings.....................................................................................................................7 The North Australian Workers Union in the 1920s and ’30s.....................................9 Comintern Influence..................................................................................................12 The 1930s....................................................................................................................15 Aboriginal-Led Organisations & the Day of Mourning............................................19 Struggles in the 1940s: The Pilbara Stock Workers’ Strike........................................23 The 1940s: Communists -

Faith Bandler Ac - Condolences

COUNCIL 23 FEBRUARY 2015 ITEM 3.3. FAITH BANDLER AC - CONDOLENCES FILE NO: S051491 MINUTE BY THE LORD MAYOR To Council: On 27 May 1967, over 90 per cent of Australians voted to amend the Commonwealth Constitution to advance the position of Aboriginal Australians. That vote, the highest ever recorded at an Australian referendum, was the outcome of a campaign waged for more than 10 years. On 13 February 2015, Faith Bandler, one of the tireless leaders of that campaign, was lost to Australia. Faith Bandler was born on 13 February 1918 of a South Seas Islander father and a Scottish-Indian mother. Her father, Peter, had been kidnapped from his home on Ambrym Island, Vanuatu at around 13 years of age and transported to Queensland where he was forced to work on a sugar cane plantation. He later escaped to NSW where he met and married Faith’s mother. They established a small banana farm near Murwillumbah where Faith spent her early years. While Faith did not know her father well (he died when she was five years old), stories about his harsh experiences as a slave labourer strongly influenced her activism. Faith moved to Sydney in 1934, living in Kings Cross, later admitting she “always had a yen for bright lights” and “wanted to have a life of my own”. She completed a short apprenticeship in a shirt factory and worked for a time making clothes. When World War II started, she joined the Women’s Land Army, and worked on fruit farms. While working in the Riverina, she first “saw the appalling conditions that Aborigines lived in”. -

M Last Visitor Management Strategy 3-5-05

Visitor Management Strategy And Cultural Site Protection Strategy [Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands] Contributors: Writer: Traditional Owners and Family Members Mike Last from all communities across the APY-Lands 21 st December 04 to including the Indigenous Land Managed Areas 31 st August 05 [Apara, Kalka-Pipalyatjara, Walalkara, Sandy’s Bore & Watarru] APY Land Management Staff and Field Colleagues Contents Outline 3 Introduction 5 Early Strategies 7 Traditional Strategies 10 Self Determination and Self Management Strategies 12 Pitjantjatjara Land Rights Strategies 15 Enterprise Strategies 19 Staff Employment Strategies 23 Summary of Strategies 25 Review of Strategies 28 Key Cultural Sites 30 Recommendations 33 Maps 34 Acknowledgements 35 References 36 Appendix I 37 Appendix II 39 Appendix III 42 Appendix IV 48 Appendix V 52 2 Outline Visitor management and the provision of site protection are not new concepts for Pitjantjantjara and Yankunytjatjara people. Hence this article is an attempt to examine the strategies that have been developed and used on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Lands from traditional times until the present day. During this period it was found that as government policies and the social climate within Australia changed, more opportunities became available to improve strategies on the Lands. These improvements are only effective provided they are supported with sufficient resources including finance. Pitjantjantjara and Yankunytjatjara people (Anangu) are able to successfully manage visitors and protect cultural sites on their Lands providing they are fully supported by those who partner with them. The section on “Early Strategies” assesses those strategies developed after the establishment of western culture in Australia. “Traditional Strategies” briefly describes those used since Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara culture began.