The Aboriginal Struggle & the Left

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recorder 298.Pages

RECORDER RecorderOfficial newsletter of the Melbourne Labour History Society (ISSN 0155-8722) Issue No. 298—July 2020 • From Sicily to St Lucia (Review), Ken Mansell, pp. 9-10 IN THIS EDITION: • Oil under Troubled Water (Review), by Michael Leach, pp. 10-11 • Extreme and Dangerous (Review), by Phillip Deery, p. 1 • The Yalta Conference (Review), by Laurence W Maher, pp. 11-12 • The Fatal Lure of Politics (Review), Verity Burgmann, p. 2 • The Boys Who Said NO!, p. 12 • Becoming John Curtin and James Scullin (Review), by Nick Dyrenfurth, pp. 3-4 • NIBS Online, p. 12 • Dorothy Day in Australia, p. 4 • Union Education History Project, by Max Ogden, p. 12 • Tribute to Jack Mundey, by Verity Burgmann, pp. 5-6 • Graham Berry, Democratic Adventurer, p. 12 • Vale Jack Mundey, by Brian Smiddy, p. 7 • Tribune Photographs Online, p. 12 • Batman By-Election, 1962, by Carolyn Allan Smart & Lyle Allan, pp. 7-8 • Melbourne Branch Contacts, p. 12 • Without Bosses (Review), by Brendan McGloin, p. 8 Extreme and Dangerous: The Curious Case of Dr Ian Macdonald Phillip Deery His case parallels that of another medical doctor, Paul Reuben James, who was dismissed by the Department of Although there are numerous memoirs of British and Repatriation in 1950 for opposing the Communist Party American communists written by their children, Dissolution Bill. James was attached to the Reserve Australian communists have attracted far fewer Officers of Command and, to the consternation of ASIO, accounts. We have Ric Throssell’s Wild Weeds and would most certainly have been mobilised for active Wildflowers: The Life and Letters of Katherine Susannah military service were World War III to eventuate, as Pritchard, Roger Milliss’ Serpent’s Tooth, Mark Aarons’ many believed. -

A Call for the Revolutionary Regroupment of the Australian Left

A Call for the Revolutionary Regroupment of the Australian Left http://www.softdawn.net/Archive/MRM/thecall.html September 1975 Melbourne Revolutionary Marxists Introduction (2017) by Robert Dorning and Ken Mansell Momentous changes occurred in Western societies in the 1960s and 70s. A wave of youth radicalisation swept many Western countries. Australia was part of this widespread generational change. The issues were largely common, but varied in importance from country to country. In Australia, the Vietnam War and conscription were major issues. This radicalisation included the demand for major political change, and new political movements and far-left organisations came into being. A notable new development in Australia was the emergence of Trotskyist groupings. However, as the wider movement subsided with Australia's withdrawal from the Vietnam War, the Australian Left became fragmented and more divided than ever. It was in this environment that, in 1975, "A Call for the Revolutionary Regroupment of the Australian Left" was published by the "Melbourne Revolutionary Marxists" (MRM). "The Call" includes a description of the evolution of the new Left movements in Australia including the Trotskyist current to which MRM belonged. MRM was a break-away from the Communist League, an Australian revolutionary socialist organisation adhering to the majority section of the Fourth International. At the Easter 1975 National Conference, virtually the entire Melbourne branch of the CL resigned en masse from the national organisation. The issue was the refusal of the national organisation to accept the application by Robert Dorning (a leading Melbourne member) for full membership on the grounds he held a "bureaucratic collectivist" position on the social nature of the Soviet Union, rather than the orthodox Trotskyist position of "deformed workers' state". -

Profile: Fred Paterson

Fred Paterson The Rhodes Scholar and theological student who became Australia's first Communist M.P. By TOM LARDNER Frederick Woolnough Paterson deserves more than the three lines he used to get in Who’s Who In Australia. As a Member of Parliament he had to be included but his listing could not have been more terse: PATERSON, Frederick Woolnough, M.L.A. for Bowen (Qld.) 1944-50; addreii Maston St., Mitchelton, Qld. Nothing like the average 20 lines given to most of those in Who’s Who, many with much less distinguished records. But then Fred Paterson had the disadvantage—or was it the distinction?—of being a Communist Member of Parliament— in fact, Australia’s first Communist M.P. His academic record alone should have earned him a more prominent listing, but this was never mentioned:— A graduate in Arts at the University of Queensland, Rhodes Scholar for Queensland, graduate in Arts at Oxford University, with honors in theology, and barrister-at-law. He was also variously, a school teacher in history, classics and mathematics; a Workers’ Educational Association organiser, a pig farmer, and for most o f the time from 1923 until this day an active member of the Communist Party of Australia, a doughty battler for the under-privileged. He also saw service in World War I. Page 50— AUSTRALIAN LBFT REVIEW, AUG.-SEPT., 1966. Fred Paterson was born in Gladstone, Central Queensland in 1897, of a big (five boys and four girls) and poor family. His father, who had emigrated from Scotland at the age of 16, had been a station manager and horse and bullock teamster in the pioneer days of Central Queensland; but for most of Fred’s boyhood, he tried to eke out a living as a horse and cart delivery man. -

The Communist Party Dissolution Act 1950

82 The Communist Party Dissolution Act 1950 After the Second World War ended with the defeat of Germany and Japan in 1945, a new global conflict between Communist and non-Communist blocs threatened world peace. The Cold War, as it was called, had substantial domestic repercussions in Australia. First, the spectre of Australians who were committed Communists perhaps operating as fifth columnists in support of Communist states abroad haunted many in the Labor, Liberal and Country parties. The Soviet Union had been an ally for most of the war, and was widely understood to have been crucial to the defeat of Nazism, but was now likely to be the main opponent if a new world war broke out. The Communist victory in China in 1949 added to these fears. Second, many on the left feared persecution, as anti-Communist feeling intensified around the world. Such fears were particularly fuelled by the activities of Senator Joe McCarthy in the United States of America. McCarthy’s allegations that Communists had infiltrated to the highest levels of American government gave him great power for a brief period, but he over-reached himself in a series of attacks on servicemen in the US Army in 1954, after which he was censured by the US Senate. Membership of the Communist Party of Australia peaked at around 20,000 during the Second World War, and in 1944 Fred Paterson won the Queensland state seat of Bowen for the party. Although party membership began to decline after the war, many Communists were prominent in trade unions, as well as cultural and literary circles. -

The History of NAIDOC Celebrating Indigenous Culture

The History of NAIDOC Celebrating Indigenous Culture latrobe.edu.au CRICOS Provider 00115M Wominjeka Welcome La Trobe University 22 Acknowledgement La Trobe University acknowledges the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nations as the traditional custodians of the land upon which the Bundoora campus is located. LaLa Trobe Trobe University University 33 Acknowledgement We recognise their ongoing connection to the land and value the unique contribution the Wurundjeri people and all Indigenous Australians make to the University and the wider Australian society. LaLa Trobe Trobe University University 44 What is NAIDOC? NAIDOC stands for the ‘National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee’. This committee was responsible for organising national activities during NAIDOC Week and its acronym has since become the name of the week itself. La Trobe University 55 History of NAIDOC NAIDOC Week celebrations are held across Australia each July to celebrate the history, culture and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. NAIDOC is celebrated not only in Indigenous communities, but by Australians from all walks of life. La Trobe University 66 History of NAIDOC 1920-1930 Before the 1920s, Aboriginal rights groups boycotted Australia Day (26 January) in protest against the status and treatment of Indigenous Australians. Several organisations emerged to fill this role, particularly the Australian Aborigines Progressive Association (AAPA) in 1924 and the Australian Aborigines League (AAL) in 1932. La Trobe University 77 History of NAIDOC 1930’s In 1935, William Cooper, founder of the AAL, drafted a petition to send to King George V, asking for special Aboriginal electorates in Federal Parliament. The Australian Government believed that the petition fell outside its constitutional Responsibilities William Cooper (c. -

Day of Mourning – Overview Fact Sheet

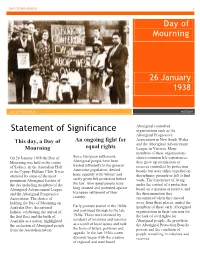

DAY OF MOURNING 1 Day of Mourning 26 January 1938 DAY OF MOURNING HISTORY Aboriginal controlled Statement of Significance organisations such as the Aboriginal Progressive Association in New South Wales An ongoing fight for This day, a Day of and the Aboriginal Advancement Mourning equal rights League in Victoria. Many members of these organisations On 26 January 1938 the Day of Since European settlement, shared common life experiences; Mourning was held in the centre Aboriginal people have been they grew up on missions or of Sydney, in the Australian Hall treated differently to the general reserves controlled by protection at the Cyprus Hellene Club. It was Australian population; denied boards but were either expelled on attended by some of the most basic equality with 'whites' and disciplinary grounds or left to find prominent Aboriginal leaders of rarely given full protection before work. The experience of living the day including members of the the law. Aboriginal people have under the control of a protection Aboriginal Advancement League long resisted and protested against board on a mission or reserve, and and the Aboriginal Progressive European settlement of their the discrimination they Association. The choice of country. encountered when they moved holding the Day of Mourning on away from these places, united the Australia Day, the national Early protests started in the 1840s members of these early Aboriginal holiday celebrating the arrival of and continued through to the late organisations in their concerns for the first fleet and the birth of 1920s. These were initiated by the lack of civil rights for Australia as a nation, highlighted residents of missions and reserves Aboriginal people, the growth in the exclusion of Aboriginal people as a result of local issues and took the Aboriginal Protection Board's from the Australian nation. -

Gladys Nicholls: an Urban Aboriginal Leader in Post-War Victoria

Gladys Nicholls: An Urban Aboriginal Leader in Post-war Victoria Patricia Grimshaw School of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC. 3010 [email protected] Abstract: Gladys Nicholls was an Aboriginal activist in mid-20 th century Victoria who made significant contributions to the development of support networks for the expanding urban Aboriginal community of inner-city Melbourne. She was a key member of a talented group of Indigenous Australians, including her husband Pastor Doug Nicholls, who worked at a local, state and national level to improve the economic wellbeing and civil rights of their people, including for the 1967 Referendum. Those who knew her remember her determined personality, her political intelligence and her unrelenting commitment to building a better future for Aboriginal people. Keywords: Aboriginal women, Aboriginal activism, Gladys Nicholls, Pastor Doug Nicholls, assimilation, Victorian Aborigines Advancement League, 1967 Referendum Gladys Nicholls (1906–1981) was an Indigenous leader who was significant from the 1940s to the 1970s, first, in action to improve conditions for Aboriginal people in Melbourne and second, in grassroots activism for Indigenous rights across Australia. When the Victorian government inscribed her name on the Victorian Women’s Honour Roll in 2008, the citation prepared by historian Richard Broome read as follows: ‘Lady Gladys Nicholls was an inspiration to Indigenous People, being a role model for young women, a leader in advocacy for the rights of Indigenous people as well as a tireless contributor to the community’. 1 Her leadership was marked by strong collaboration and co-operation with like-minded women and men, both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, who were at the forefront of Indigenous reform, including her prominent husband, Pastor (later Sir) Doug Nicholls. -

SEVEN WOMEN of the 1967 REFERENDUM Project For

SEVEN WOMEN OF THE 1967 REFERENDUM Project for Reconciliation Australia 2007 Dr Lenore Coltheart There are many stories worth repeating about the road to the Referendum that removed a handful of words from Australia’s Constitution in 1967. Here are the stories of seven women that tell how that road was made. INTRODUCING: SHIRLEY ANDREWS FAITH BANDLER MARY BENNETT ADA BROMHAM PEARL GIBBS OODGEROO NOONUCCAL JESSIE STREET Their stories reveal the prominence of Indigenous and non-Indigenous women around Australia in a campaign that started in kitchens and local community halls and stretched around the world. These are not stories of heroines - alongside each of those seven women were many other men and women just as closely involved. And all of those depended on hundreds of campaigners, who relied on thousands of supporters. In all, 80 000 people signed the petition that required Parliament to hold the Referendum. And on 27 May 1967, 5 183 113 Australians – 90.77% of the voters – made this the most successful Referendum in Australia’s history. These seven women would be the first to point out that it was not outstanding individuals, but everyday people working together that achieved this step to a more just Australia. Let them tell us how that happened – how they got involved, what they did, whether their hopes were realised – and why this is so important for us to know. 2 SHIRLEY ANDREWS 6 November 1915 - 15 September 2001 A dancer in the original Borovansky Ballet, a musician whose passion promoted an Australian folk music tradition, a campaigner for Aboriginal rights, and a biochemist - Shirley Andrews was a remarkable woman. -

Aboriginal Art - Resistance and Dialogue

University of New South Wales College of Fine Arts School of Art Theory ABORIGINAL ART - RESISTANCE AND DIALOGUE The Political Nature and Agency of Aboriginal Art A thesis submitted by Lee-Anne Hall in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Art Theory CFATH709.94/HAL/l Ill' THE lJNIVERSllY OF NEW SOUTH WALES COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS Thesis/Project Report Sheet Surnune or Funily .nune· .. HALL .......................................................................................................................................................-....... -............ · · .... U · · MA (TH' rn ....................................... AbbFinlname: . ·......... ' ....d ........... LEE:::ANNE ......................lend.............. ................. Oher name/1: ..... .DEBaaAH. ....................................- ........................ -....................... .. ,CVlalJOn, or C<ltal &1YCOIn '"" NVCfllt)'ca It:.... ..................... ( ............................................ School:. .. ART-����I��· ...THEORY ....... ...............................··N:t�;;�?A�c·���JlacjTn·ar··................................... Faculty: ... COLLEGE ... OF. ...·Xr"t F.J:blll:...................... .AR'J: ..................... .........................-........................ n,1e:........ .................... •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• .. •••••• .. •••••••••••••••••••••••••• .. •• • .. ••••• .. ••••••••••• ..••••••• .................... H ................................................................ -000000000000••o00000000 -

August 5, 1976 / 3W *

August 5, 1976 / 3W * PEACE AND FREEDOM THRUI NONVIOLENT ACT¡ON Seeking a Human Perspective on Housing How the'Vietnam War lsn't Over for Somã People Bird-Brained Schemes in the Pentagon Are Alternative lnstitutions the Way to Social Change? August Ir The 31st Anniversary of Hiroshima; For observances, see Events, page 17 1. \ ¡.ç "dltfiþ't'* *---lr^ ,qsl{r^-.{¡se***, å{-!¡t- ,l I am convinced that his present she cites show that he is not a pacifist, .¡ detention by the Lee Kuan Yew govern- perhdps) but they say nothing about the ment is for punitive reasons and NAEP. fgpPression of politicians who oppose 2) The WA\{-WSO is fïlled with hrs government. people who were in defense work. Just I appeal to all peace loving people all because a person once did defense work over the world to-once again help does not mean that hej or she only.does achieve the release not õnly ofmy evil thingb. husband Dr. Poh Soo Kai, but aliother 3) Iknow very little about the BECOMING REAI political prisoners such as Dr. Lim Hock world, but I doubt business that sub- are two ways, in thè stories at least. Siew, Said Zahari, Ho Piow and manv sidiaries of large corporations have their There others who have been in prison for m'ore first is like Pinocchio, and l've done it, projects.dictated to them by their þarent The than 13 years. I demand the PAP companies, or that the parent Through good works, and self-denial, and an enterpr¡s¡ng governrñent allow my husband to to companies have total access to the Conscience, and the only reward ' August 5,1976 l,Yol, Xll, No. -

Full Thesis Draft No Pics

A whole new world: Global revolution and Australian social movements in the long Sixties Jon Piccini BA Honours (1st Class) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2013 School of History, Philosophy, Religion & Classics Abstract This thesis explores Australian social movements during the long Sixties through a transnational prism, identifying how the flow of people and ideas across borders was central to the growth and development of diverse campaigns for political change. By making use of a variety of sources—from archives and government reports to newspapers, interviews and memoirs—it identifies a broadening of the radical imagination within movements seeking rights for Indigenous Australians, the lifting of censorship, women’s liberation, the ending of the war in Vietnam and many others. It locates early global influences, such as the Chinese Revolution and increasing consciousness of anti-racist struggles in South Africa and the American South, and the ways in which ideas from these and other overseas sources became central to the practice of Australian social movements. This was a process aided by activists’ travel. Accordingly, this study analyses the diverse motives and experiences of Australian activists who visited revolutionary hotspots from China and Vietnam to Czechoslovakia, Algeria, France and the United States: to protest, to experience or to bring back lessons. While these overseas exploits, breathlessly recounted in articles, interviews and books, were transformative for some, they also exposed the limits of what a transnational politics could achieve in a local setting. Australia also became a destination for the period’s radical activists, provoking equally divisive responses. -

Australian Aboriginal Verse 179 Viii Black Words White Page

Australia’s Fourth World Literature i BLACK WORDS WHITE PAGE ABORIGINAL LITERATURE 1929–1988 Australia’s Fourth World Literature iii BLACK WORDS WHITE PAGE ABORIGINAL LITERATURE 1929–1988 Adam Shoemaker THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS iv Black Words White Page E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Previously published by University of Queensland Press Box 42, St Lucia, Queensland 4067, Australia National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Black Words White Page Shoemaker, Adam, 1957- . Black words white page: Aboriginal literature 1929–1988. New ed. Bibliography. Includes index. ISBN 0 9751229 5 9 ISBN 0 9751229 6 7 (Online) 1. Australian literature – Aboriginal authors – History and criticism. 2. Australian literature – 20th century – History and criticism. I. Title. A820.989915 All rights reserved. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organization. All electronic versions prepared by UIN, Melbourne Cover design by Brendon McKinley with an illustration by William Sandy, Emu Dreaming at Kanpi, 1989, acrylic on canvas, 122 x 117 cm. The Australian National University Art Collection First edition © 1989 Adam Shoemaker Second edition © 1992 Adam Shoemaker This edition © 2004 Adam Shoemaker Australia’s Fourth World Literature v To Johanna Dykgraaf, for her time and care