The Red North

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Workingman's Paradise": Pioneering Socialist Realism

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online William Lane's "The Workingman's Paradise": Pioneering Socialist Realism Michael Wilding For their part in the 1891 Australian shearers' strike, some 80 to 100 unionists were convicted in Queensland with sentences ranging from three months for 'intimidation' to three years for 'conspiracy'. It was to aid the families of the gaoled unionists that William Lane wrote The Workingman's Paradise (1892). 'The first part is laid during the summer of 1888-9 and covers two days; the second at the commencement of the Queensland bush excitement in 1891, covering a somewhat shorter time.' (iii) The materials of the shearers' strike and the maritime strike that preceded it in 1890 are not, then, the explicit materials of Lane's novel. But these political confrontations are the off-stage reference of the novel's main characters. They are a major unwritten, but present, component of the novel. The second chapter of part II alludes both to the defeat of the maritime strike and the beginnings ofthe shearers' strike, forthcoming in the novel's time, already defeated in the reader's time. Those voices preaching moderation in the maritime strike, are introduced into the discussion only to be discounted. The unionists who went round 'talking law and order to the chaps on strike and rounding on every man who even boo'd as though he were a blackleg' have realised the way they were co-opted and used by the 'authorities'. 'The man who told me vowed it would be a long time before he'd do policeman's work again. -

Profile: Fred Paterson

Fred Paterson The Rhodes Scholar and theological student who became Australia's first Communist M.P. By TOM LARDNER Frederick Woolnough Paterson deserves more than the three lines he used to get in Who’s Who In Australia. As a Member of Parliament he had to be included but his listing could not have been more terse: PATERSON, Frederick Woolnough, M.L.A. for Bowen (Qld.) 1944-50; addreii Maston St., Mitchelton, Qld. Nothing like the average 20 lines given to most of those in Who’s Who, many with much less distinguished records. But then Fred Paterson had the disadvantage—or was it the distinction?—of being a Communist Member of Parliament— in fact, Australia’s first Communist M.P. His academic record alone should have earned him a more prominent listing, but this was never mentioned:— A graduate in Arts at the University of Queensland, Rhodes Scholar for Queensland, graduate in Arts at Oxford University, with honors in theology, and barrister-at-law. He was also variously, a school teacher in history, classics and mathematics; a Workers’ Educational Association organiser, a pig farmer, and for most o f the time from 1923 until this day an active member of the Communist Party of Australia, a doughty battler for the under-privileged. He also saw service in World War I. Page 50— AUSTRALIAN LBFT REVIEW, AUG.-SEPT., 1966. Fred Paterson was born in Gladstone, Central Queensland in 1897, of a big (five boys and four girls) and poor family. His father, who had emigrated from Scotland at the age of 16, had been a station manager and horse and bullock teamster in the pioneer days of Central Queensland; but for most of Fred’s boyhood, he tried to eke out a living as a horse and cart delivery man. -

The Communist Party Dissolution Act 1950

82 The Communist Party Dissolution Act 1950 After the Second World War ended with the defeat of Germany and Japan in 1945, a new global conflict between Communist and non-Communist blocs threatened world peace. The Cold War, as it was called, had substantial domestic repercussions in Australia. First, the spectre of Australians who were committed Communists perhaps operating as fifth columnists in support of Communist states abroad haunted many in the Labor, Liberal and Country parties. The Soviet Union had been an ally for most of the war, and was widely understood to have been crucial to the defeat of Nazism, but was now likely to be the main opponent if a new world war broke out. The Communist victory in China in 1949 added to these fears. Second, many on the left feared persecution, as anti-Communist feeling intensified around the world. Such fears were particularly fuelled by the activities of Senator Joe McCarthy in the United States of America. McCarthy’s allegations that Communists had infiltrated to the highest levels of American government gave him great power for a brief period, but he over-reached himself in a series of attacks on servicemen in the US Army in 1954, after which he was censured by the US Senate. Membership of the Communist Party of Australia peaked at around 20,000 during the Second World War, and in 1944 Fred Paterson won the Queensland state seat of Bowen for the party. Although party membership began to decline after the war, many Communists were prominent in trade unions, as well as cultural and literary circles. -

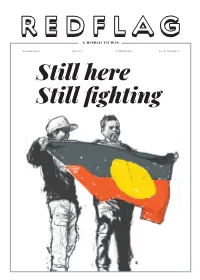

RF177.Pdf (Redflag.Org.Au)

A WORLD TO WIN REDFLAG.ORG.AU ISSUE #177 19 JANUARY 2021 $3 / $5 (SOLIDARITY) Still here Still fi ghting REDFLAG | 19 JANUARY 2021 PUBLICATION OF SOCIALIST ALTERNATIVE REDFLAG.ORG.AU 2 Red Flag Issue # 177 19 January 2021 ISSN: 2202-2228 Published by Red Flag Support the Press Inc. Trades Hall 54 Victoria St Carlton South Vic 3053 [email protected] Christmas Island (03) 9650 3541 Editorial committee Ben Hillier Louise O’Shea Daniel Taylor Corey Oakley rioters James Plested Simone White fail nonetheless. Some are forced to complete rehabil- Visual editor itation programs and told that when they do so their James Plested appeals will be strengthened. They do it. They fail. These are men with families in Australia. They Production are workers who were raising children. They are men Tess Lee Ack n the first week of 2021, detainees at the Christ- who were sending money to impoverished family Allen Myers mas Island Immigration Detention Centre be- members in other countries. Now, with their visas can- Oscar Sterner gan setting it alight. A peaceful protest, which celled, they have no incomes at all. This has rendered Subscriptions started on the afternoon of 5 January, had by partners and children homeless. and publicity evening escalated into a riot over the treatment Before their transportation from immigration fa- Jess Lenehan Iof hundreds of men there by Home Affairs Minister cilities and prisons on the Australian mainland, some Peter Dutton and his Australian Border Force. Four of these men could receive visits from loved ones. Now What is days later, facing down reinforced numbers of masked, they can barely, if at all, get internet access to speak to armed Serco security thugs and Australian Federal them. -

INAUGURAL SPEECH Mr SKELTON (Nicklin—ALP) (11.18 Am): I Would Like to Begin by Acknowledging the First Nation People on Whose Land We Meet: the Turrbal People

Speech By Robert Skelton MEMBER FOR NICKLIN Record of Proceedings, 1 December 2020 INAUGURAL SPEECH Mr SKELTON (Nicklin—ALP) (11.18 am): I would like to begin by acknowledging the First Nation people on whose land we meet: the Turrbal people. I also acknowledge the Kabi Kabi people, whose land I am honoured to speak of in this place, and I pay my respects to their leaders past, present and emerging. I was born an Army brat and spent my early life travelling around the country with my family and sister Cassandra as my father, Robert, served. My mother, Yvonne, also imbued in me a sense of duty and honour, so in 1995 after finishing school in Townsville I joined the Navy so that I, too, could serve my country. My naval career saw me serve as a boatswain’s mate on HMAS Swan, HMAS Canberra and HMAS Ipswich. I later had an educational posting at the gunnery range at HMAS Cerberus. In 2002 I transferred to RAAF Base Amberley to train as an aviation firefighter. I then served at RAAF Base Tindal. My time in the services taught me the importance of comradeship, teamwork, improvisation and a love of, and duty to, country. During this time my wife, Rachel, and I had a young family. I have three beautiful children: Brandt, Delaney and Jamison. All three were born thousands of kilometres apart in Cairns, Frankston and Katherine respectively. I also had the good fortune of adopting Ray and Sandra Hubbard and John and Julie Aldous as parents somewhere along the way. -

Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia 1788-1930: Sources

Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia 1788-1930: Sources © Ryan, Lyndall; Pascoe, William; Debenham, Jennifer; Gilbert, Stephanie; Richards, Jonathan; Smith, Robyn; Owen, Chris; Anders, Robert J; Brown, Mark; Price, Daniel; Newley, Jack; Usher, Kaine, 2019. The information and data on this site may only be re-used in accordance with the Terms Of Use. This research was funded by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council, PROJECT ID: DP140100399. http://hdl.handle.net/1959.13/1340762 Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia 1788-1930: Sources 0 Abbreviations 1 Unpublished Archival Sources 2 Battye Library, Perth, Western Australia 2 State Records of NSW (SRNSW) 2 Mitchell Library - State Library of New South Wales (MLSLNSW) 3 National Library of Australia (NLA) 3 Northern Territory Archives Service (NTAS) 4 Oxley Memorial Library, State Library Of Queensland 4 National Archives, London (PRO) 4 Queensland State Archives (QSA) 4 State Libary Of Victoria (SLV) - La Trobe Library, Melbourne 5 State Records Of Western Australia (SROWA) 5 Tasmanian Archives And Heritage Office (TAHO), Hobart 7 Colonial Secretary’s Office (CSO) 1/321, 16 June, 1829; 1/316, 24 August, 1831. 7 Victorian Public Records Series (VPRS), Melbourne 7 Manuscripts, Theses and Typescripts 8 Newspapers 9 Films and Artworks 12 Printed and Electronic Sources 13 Colonial Frontier Massacres In Australia, 1788-1930: Sources 1 Abbreviations AJCP Australian Joint Copying Project ANU Australian National University AOT Archives of Office of Tasmania -

Romantic Nationalism and the Descent Into Myth

Romantic Nationalism and the Descent into Myth: William Lane's Th e Wo rkingman 's Paradise ANDREW McCANN University of Melbourne he study of Australian lit�rature has been and no doubt still is a fo rm of nationalist pedagogy in which the primary object of nationalist discourse, the people, is emblematisedT in the fo rmation of a literary culture. The easy simultaneity of text and populace implied here is a recurring trope in the writing of Australian cultural history. Needless to say the 1890s is the decade that most clearly embodies this simul taneity in its foregrounding of an apparent movement from Romanticism to a more directly political realism. The narrative of the people's becoming, in other words, involves a stylistic shift that is seen as integral to, even constitutive of, political consciousness in the years before Federation. By this reckoning, the shift to realism concretises the perception of locality, the sense of time and space, we associate \•lith the nation. Realism effects, in Mikhail Bakhtin's words, 'a creative humanisation of this locality, which transforms a part of terrestrial space into a place of historical life for people' (31). The trouble with this version of Australian literary history is that it mistakes obvious stylistic differences for a genuine and radical discursive shift. In positing the movement from Romanticism to realism as the key to national becoming it assumes a direct correspondence between the aesthetic and the ideological. This elides what, looking from a slightly different angle, is equally obvious about late-nineteenth Ct'ntury Australian nationalism, and perhaps nationalism in general: that is, the nation, with its attendant notions of organically bonded community, locality and autochthony, is not simply haunted by Romanticism, it is unambiguously Romantic. -

A History of the Relationship Between the Queensland Branch of the Australian Workers’ Union (AWU) and the Labour Movement in Queensland from 1913-1957

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year A history of the relationship between the Queensland branch of the Australian Workers’ Union (AWU) and the labour movement in Queensland from 1913-1957 Craig Clothier University of Wollongong Clothier, Craig, A history of the relationship between the Queensland branch of the Australian Workers’ Union (AWU) and the labour movement in Queensland from 1913-1957, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2005. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1996 This paper is posted at Research Online. Chapter 6 Sweet Surrender: The Rise and Demise of MiHtancy in Queensland, 1933-1939 'let me here point out that Labor ... has never been defeated by its enemies. Defeat always comes from its own ranks.' William Demaine, Presidential Address, Labor-in- Politics Convention, 1938. Having secured the defeat of the Moore Government in the 1932 state elections, Forgan-Smith and the ALP in Queensland were now charged with the responsibility of fulfilling the promises made to the Queensland electorate. Getting Queenslanders working again and dragging the economy out of a crippling depression were the 218 cornerstones of Labors electoral resurrection. For this to occur one of the requirements of the labour movement was to ensure a climate of industrial peace and resist calls for direct industrial action. As ever the Labor Party would look to its foremost political and industrial ally the AWU to enforce the compliance of trade unionists through its reliance upon the arbitration system. For the AWU the immediate goals were to restore the power and prestige of the Arbitration Court which had been emasculated by the Moore administration and to retrieve the many employment conditions which his government had eroded. -

(AWU) and the Labour Movement in Queensland from 1913-1957

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year A history of the relationship between the Queensland branch of the Australian Workers’ Union (AWU) and the labour movement in Queensland from 1913-1957 Craig Clothier University of Wollongong Clothier, Craig, A history of the relationship between the Queensland branch of the Australian Workers’ Union (AWU) and the labour movement in Queensland from 1913-1957, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2005. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1996 This paper is posted at Research Online. Introduction Between 1913-1957 the Queensland Branch of the Australian Workers' Union (AWU) was the largest branch of the largest trade union in Australia. Throughout this period in Queensland the AWU accounted for approximately one third of all trade unionists in that state and at its peak claimed a membership in excess of 60 000. Consequenfly the AWU in Queensland was able to exert enormous influence over the labour movement in that state not only in industrial relations but also within the political sphere through its affiliation to the Australian Labor Party. From 1915-1957 the Labor Party in Queensland held office for all but the three years between 1929-1932. AWU officials and members dominated the Labor Cabinets of the period and of the eight Labor premiers five were members of the AWU, with two others closely aligned to the Union. Only the last Labor premier of the period, Vincent Clare Gair, owed no allegiance to the AWU. The AWU also used its numerical strength and political influence to dominate the other major decision-making bodies of Queensland's labour movement, most notably the Queensland Central Executive (QCE), that body's 'inner' Executive and the triennial Labor-in-Politics Convention. -

Australian Studies Journal 31/2017

Im Namen der Gesellschaft für Published on behalf of the Australienstudien herausgegeben Association for Australian Studies von by Henriette von Holleuffer, Hamburg, Germany – [email protected] Oliver Haag, The University of Edinburgh, School of History Classics and Archaeology, Teviot Place, EH8 9AG, UK – [email protected] Bitte senden Sie alle Korrespondenz und Manu- Please send all correspondence and manuscripts skripte an die Herausgeber. Manuskripte, die an- to the editors. Manuscripts that have been pub- derswo erschienen sind, werden nur nach Rück- lished elsewhere will, in special cases, be consid- sprache zur Veröffentlichung angenommen. Eine ered for publication. A republication elsewhere is nachträgliche, anderweitige Veröffentlichung ist possible upon prior consultation with the editors. It nach Rücksprache mit dem Herausgeber möglich, is expected that the subsequent publication carries wobei ein Verweis auf dieses Organ erwartet wird. a reference to this periodical. Contributions to this journal are fully refereed by members of the ZfA | ASJ Advisory Board: Rudolf Bader, PH Zurich l Elisabeth Bähr, Speyer l Jillian Barnes, University of Newcastle l Nicholas Birns, Eugene Lang College, New York City l Boris Braun, University of Cologne l David Callahan, Universidade de Aveiro, Portugal l Maryrose Casey, Monash University l Ann Curthoys, University of Sydney l Brian Dibble, University of Western Australia (em.) | Corinna Erckenbrecht, Cologne/Görlitz l Gerhard Fischer, University of New South Wales l Victoria Grieves, -

Brisbane Used to Be Called the Deep North

Radical Media in the Deep North: The origins of 4ZZZ-FM by Alan Knight PhD Brisbane used to be called the Deep North. It spoke of a place where time passed slowly in the summer heat, where rednecks ran the parliament and the press, blacks died from beatings and the police thought themselves above the law. Even though Brisbane is situated in the bottom southeast quarter of the great northern state of Queensland, it's sobriquet represented a state of mind. Queensland was described as a cultural backwater lacking bookshops, political pubs, radio and television network headquarters and the publishing centres where Australian intellectuals could be seen and heard. It was fashionable, then as now, for many in Sydney and Melbourne to dismiss Queenslanders as naive, if not malignant conservatives. Yet in 1975, Brisbane created Australia's most radical politics and music station, 4ZZZ-FM. It broadcasts to this day. How did it come about and why? The Bitter Fight Queensland has a long, yet often forgotten history of conflict between conservatives and radicals. In a huge, decentralised state, the march to democracy has been signposted by demands for free speech expressed through a diversified media. ZZZ is an offspring of these battles, which were in part fought out in the state's mainstream and underground media. The bitter fight began in earnest in 1891, when Queensland shearers went on strike over work contracts. The strikers produced a flurry of cartoons, articles and satirical poems, which were passed around their camp fires. They joined armed encampments, which were broken up only after the government called in the military. -

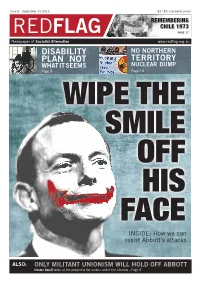

Red Flag Issue8 0.Pdf

Issue 8 - September 10 2013 $3 / $5 (solidarity price) REMEMBERING FLAG CHILE 1973 RED PAGE 17 Newspaper of Socialist Alternative www.redfl ag.org.au DISABILITY NO NORTHERN PLAN NOT TERRITORY WHAT IT SEEMS NUCLEAR DUMP Page 8 Page 13 WIPE THE SMILE OFF HIS FACE INSIDE: How we can resist Abbott’s attacks ALSO: ONLY MILITANT UNIONISM WILL HOLD OFF ABBOTT Jerome Small looks at the prospects for unions under the Liberals - Page 9 2 10 SEPTEMBER 2013 Newspaper of Socialist Alternative FLAG www.redfl ag.org.au RED CONTENTS EDITORIAL 3 How Labor let the bastards in Mick Armstrong analyses the election result. 4 Wipe the smile off Abbott’s face ALP wouldn’t stop Abbo , Diane Fieldes on what we need to do to fi ght back. now it’s up to the rest of us 5 The limits of the Greens’ leftism A lot of people woke up on Sunday leader (any leader) and wait for the 6 Where does real change come from? a er the election with a sore head. next election. Don’t reassess any And not just from drowning their policies, don’t look seriously about the Colleen Bolger makes the argument for getting organised. sorrows too determinedly the night deep crisis of Laborism that, having David confront a Goliath in yellow overalls before. The thought of Tony Abbo as developed for the last 30 years, is now prime minister is enough to make the at its most acute point. Jeremy Gibson reports on a community battling to keep McDonald’s soberest person’s head hurt.